Sick and wounded soldiers back from Iraq were warehoused in dilapidated barracks, waiting weeks or even months to see doctors. Many were not getting proper treatment for one of the signature ills of this war, post-traumatic stress disorder. Buried in a blizzard of paperwork, frustrated soldiers became ensnared in an Army bureaucracy that is supposed to provide them with medical treatment and disability payments. To make matters worse, separate efforts to care for soldiers by the Army and the Department of Veterans Affairs were duplicative and confusing.

It sounds like the headline-making scandal over Walter Reed Army Medical Center in early 2007, in the wake of which the Army surgeon general, Lt. Gen. Kevin Kiley, downplayed the problems. But these kinds of nightmarish struggles faced by ailing war veterans existed as far back as 2003, and were brought to the attention of Congress before Kiley's tenure. The Army surgeon general presiding over the crisis back then was Lt. Gen. James Peake, who, like Kiley in 2007, sought to whitewash the situation. Peake retired in July 2004 -- but now he's back in the news.

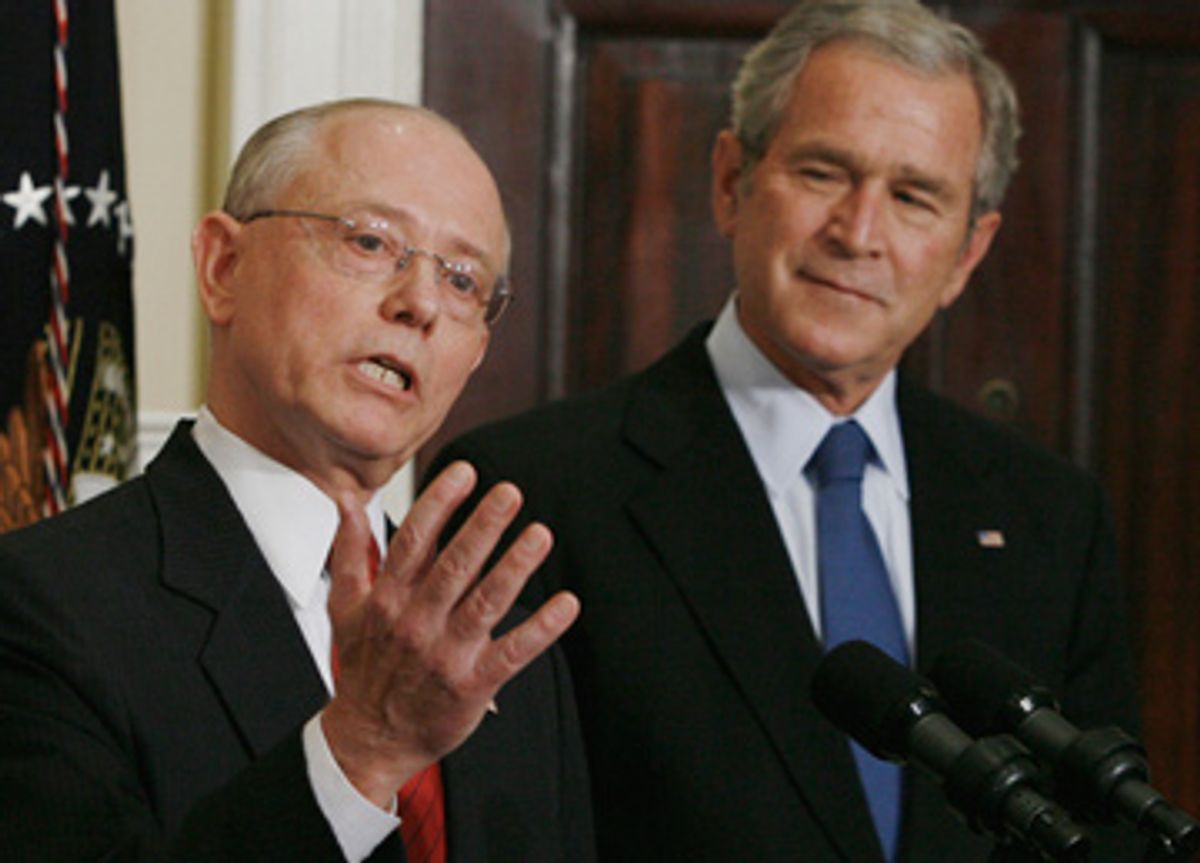

President Bush, who vowed this year to fix the mess with veterans care, is pressing Congress to enact a slate of reforms to help returning soldiers, including slashing the military healthcare bureaucracy and providing better treatment for those with PTSD. And just last week, Bush announced his nominee for the new head of the Department of Veterans Affairs -- retired Lt. Gen. James Peake.

Although Peake was in charge when the wheels started coming off Army outpatient care more than four years ago, there are no signs so far that the Senate will reject his nomination to head the VA now. Peake was wounded twice while serving in Vietnam and has more than 40 years of experience in military medicine, according to the White House. He enjoys the support of the American Legion, the country's largest veterans' service organization.

But others are outraged that Bush has chosen a fix-it man who presided over a broken system. "He is the wrong man at the wrong time, and Bush should be ashamed of this betrayal," said Paul Sullivan, director of Veterans for Common Sense. Until March 2006, Sullivan was a project manager at the VA in charge of data on returning veterans. "Peake has honorable military service," Sullivan said. "However, he failed in his position as surgeon general to fix the Walter Reed problem when he knew about it in 2003."

I first reported on the problems faced by outpatient veterans in an article published by United Press International on Oct. 17, 2003, while Peake was the Army surgeon general. Headlined "Sick, Wounded U.S. Troops Held in Squalor," the article exposed some of the same kinds of problems at Fort Stewart, Ga., that I would later write about at Walter Reed in Salon in 2005 and in 2006, and that the Washington Post would write about at Walter Reed in 2007. Warehoused in substandard barracks at Fort Stewart, hundreds of soldiers waited for doctor's appointments and got bogged down in the Army's disability paperwork, my October 2003 article showed. Many wounded or sick soldiers at Fort Stewart believed that the Army was trying to push them out with reduced benefits for their ailments.

But the problem wasn't contained to Fort Stewart; it was with the Army's outpatient care system more broadly. I filed a similar article for UPI from Fort Knox, Ky., published on Oct. 29, 2003, which discussed the more than 400 sick and injured soldiers there who were waiting weeks and sometimes months for medical treatment.

Following those reports, the Army dispatched some top brass to Fort Stewart, announced new funding for housing there, and said it was rushing doctors to Georgia to handle the patient backlog. Congress hauled military leaders to Capitol Hill to explain themselves, including Peake.

When Peake appeared before Congress in January 2004, veterans' advocates who also testified made it clear that Fort Stewart and Fort Knox were not aberrations. The system was broken, they said.

At a Jan. 21, 2004, hearing before the House Total Force Subcommittee, Steve Robinson, then executive director of the National Gulf War Resource Center, testified that soldiers coming back from Iraq were locked in a "battle for treatment, care and often fair compensation." He said the problems were "directly linked to Department of Defense Health Affairs policies." Robinson said that 10 days earlier, a soldier had hanged himself at Walter Reed, and that patients with PTSD weren't getting the help they needed. "There are shortages in qualified providers, beds, and command emphasis to treat those who need counseling most," Robinson said. He warned that "all of these things combine to create a healthcare crisis if left unattended." Robison then listed initiatives that would help returning soldiers, from increasing doctors to improving screening for PTSD. He implored military officials to act, noting "systemic problems, but they're solvable."

A soldier from Fort Stewart who testified at the same hearing, Sgt. Craig LaChance, said that soldiers at the base were denied proper medical care. "We lived in deplorable conditions," LaChance said. "We were stripped of our dignity and threatened and made to feel as if we had failed the Army."

And Patricia Hicks, director of the Citizens Advocacy Center, warned at the hearing that service members returning from war were facing a "bureaucratic hell." She described one veteran who was "forced to make his own medical appointments and was calling the medical centers trying to schedule himself for the appointments and the doctor help the he needed." Hicks said troops coming back felt that their "trust has been betrayed," that despite those troops' commitment to the military, "when they came home injured, the military didn't maintain their end of the bargain."

In his testimony, Peake responded by lauding the Army's "extraordinary quality of care, with the best people, well-equipped, well-trained, well-prepared." He said the Army was "maintaining high standards as we take care of family members back home."

Peake admitted that he had "stumbled" at places like Fort Stewart but asserted that the situation had been fixed. "The good news is, I got really good people out there who are ensuring that each soldier did get quality care all along," Peake said. He said wait-times for doctors were down and the Army had "upped the admin staff" to help patients negotiate the bureaucracy. The new staff, Peake said, would "ensure things do not fall through the cracks and there is that all-important individual attention."

Not all veterans blame Peake for failing to fix these problems back in 2003 and 2004. Rick Weidman, director of government relations at Vietnam Veterans of America, blames the Bush administration for trying to fight the war on the cheap -- including penny pinching on outpatient care and benefits. But he says generals like Peake need to make a stand and do the right thing. "Do you resign or do you salute and follow civilian authority?" Weidman asked. He wondered whether Peake, if confirmed for the job at the VA, will have the gumption to refuse to march in lockstep with the administration if he doesn't get the resources he needs to provide adequately for veterans.

The rising number of injured veterans returning from Iraq may be wondering the same.

Shares