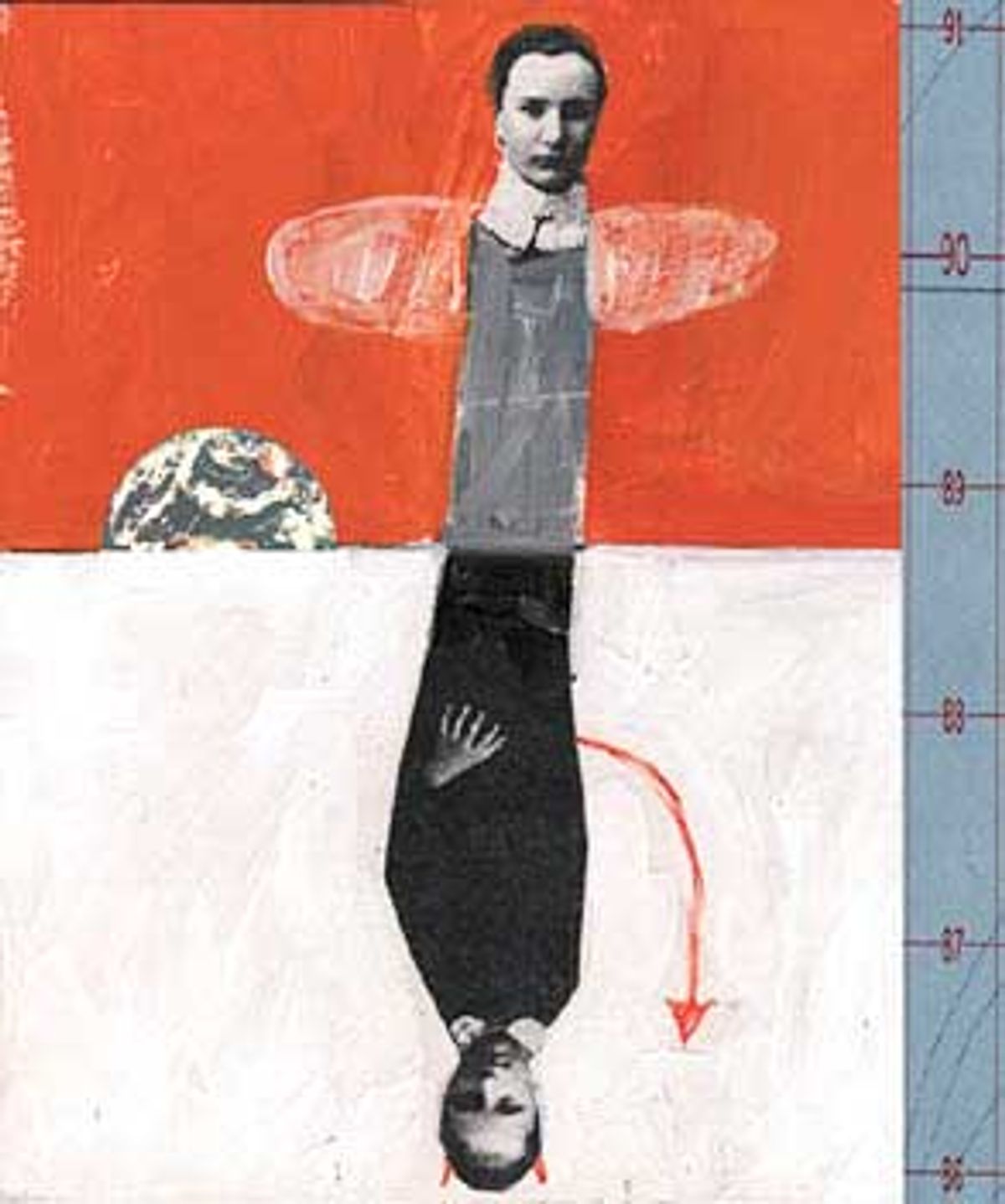

There are gaps that form in our modern world -- temporary imbalances that eventually right themselves, restoring equilibrium. Now may be one of those corrective times. The angel craze seems to have petered out and the moment could be right to address a neglected spiritual need: our deep-seated longing for hell.

We were born too late for all the comforting certainties -- old-fashioned values, death from syphilis, searing fusillades of brimstone. Once there were no situational ethics, and forget about moral relativism. Cuss on a Sunday and, presto, you were a Grade A roaster on a subterranean spit, with the deli manager on permanent break.

But such cruelty could never survive in a soft-sell age. The gradual phasing-out of a retributive afterlife model gained official approval when even the venerable Church of England gave the devil a pink slip. The church's revised theological interpretation, first unveiled several years ago, mothballed the pitchforks and doused the lake of fire. Hell, said the archbishops, is merely a state of nonbeing -- a never-ending flight delay in a timeless Des Moines. (Odd when you consider that the official head of the Church of England is Queen Elizabeth II, who might at least preserve a little scorpion-stuffed corner of purgatory for pesky daughters-in-law.)

Toward the end, hell was reduced to an occasional appearance in "The Far Side" cartoons. When Gary Larson retired, receivership was inevitable.

The C. of E.'s new doctrine merely formalized a widespread belief that a merciful God could not be reconciled with torture. (Leave that to his followers.) But when the last truckload of charcoal briquettes departed from those underground caverns, what a vacuum was left behind. Believers uncomfortable with Dante's Inferno were equally discomfited by the implied alternative -- namely, blanket forgiveness for all earthly transgressions. Heaven yes, but hell no? Wrestling with the theological implications could get painful.

One example played out on CNN in February 1998 at the execution in Texas of Karla Faye Tucker. There in the Lone Star State, where authorities are not afraid to play Old Testament God on a regular basis, the pretty, born-again multiple murderer was dispatched by lethal injection despite waves of sympathetic media attention and even some conservative Christian support. Afterward, cameras surrounded Richard Thornton outside the death house. His wife, Deborah, had been one of Tucker's victims, and now he described for the assembled media his vision of heaven. In Thornton's view Karla Faye was headed up to meet Deborah and, he predicted, "it ain't gonna be pretty." Turning his face skyward, Thornton addressed his departed wife: "Here she comes, baby doll. She's all yours."

A husband's profound grief is thoroughly understandable, but for those who choose to speculate on the world beyond, this was still a rather startling vision of paradise -- a Texas heaven where murder victims lie in the tall grass, waiting for vengeance. Perhaps the baby Jesus is right there, passing out ammo. Once you remove hell from the eternal equation, heaven finds itself being adapted for uses clearly not foreseen in the original design specs.

Now there's a move to set things right. Last month a coalition of conservative Christian denominations called the Evangelical Alliance released a report titled "The Nature of Hell," produced by a five-member committee that included an Oxford theologian. Get out the industrial drums of starter fluid -- according to the report, hell is back in business.

The concept of good and evil realms predates Christianity by many centuries. Zoroastrians believed in the existence of a Satan-like evil lord who opposed the forces of light. The Bible, in fact, is surprisingly quiet on the topic. Like the Greek Hades, which acquired negative connotations only gradually, the ancient Hebrews believed in an underworld called Sheol, not originally associated with punishment. But the Book of Daniel introduces the idea of eternal condemnation (or glory), and with the Bible's closing scenes in the Book of Revelation, the blueprint that would inspire Dante and Milton appears: Satan's lair, the bottomless pit, locusts with human faces and lion's teeth, the lake of fire.

The Evangelical Alliance does not proclaim the literal truth of Lucifer's Lagoon, but don't start with the dancing and fornicating just yet -- its report insists that undying worms, gnashing of teeth and, yes, eternal flames are legitimate symbols of the horrors awaiting those who reject Jesus. "Unimaginable torment" is what the alliance forecasts for sinners. The level of agony is dependent on the relative severity of an individual's wickedness, which seems only fair. (Although from a marketing standpoint, the evangelicals are now burdened with a tremendous disadvantage. Given the clear choice between the tortures of the damned and simple nothingness, the Church of England must be doing land office business these days. And if it's busy up here, imagine the lineups in hell.)

Metaphorical interpretations of the Inferno have long been the preferred way to reconcile warring concepts of a vengeful God with a God of divine love. "Hell is oneself," said T.S. Eliot. "Hell is other people," Jean-Paul Sartre demurred. No, said Percy Bysshe Shelley: "Hell is a city much like London." Or perhaps Buffalo, N.Y. -- (Miroslav) Satan plays hockey for the Sabres. Apparently hell really does freeze over, and the Zamboni comes out between periods.

And you may want to discount those cherubs -- hell sells, too. The owners of Hell.com have announced plans to auction their domain name for millions of dollars. (See also the career of AC/DC.)

Curiosity about worlds beyond death must be nearly as old as the human urge to explore hidden places and dark caves (which in turn allowed many humans to discover what follows death). Recently that spiritual curiosity led a Vancouver, Canada, crowd numbering several hundred to drop 15 bucks for an audience with Friedbert Karger. Karger is a 56-year-old German physicist who, while pursuing thermonuclear research, also developed an interest in less tangible realms. After embracing the philosophy of 20th century prophet Abd-ru-shin (born Oskar Ernst Bernhardt in Bischofswerda, Saxony, in 1875), Karger began touring the world speaking on behalf of the Grail Foundation, an organization dedicated to spreading Abd-ru-shin's teachings. It is the Saxon seer's comprehensive theory of life after death that Karger is in Vancouver to explain.

As soon as Karger opens his mouth, any notion that he might be some smooth New Age charlatan is instantly dispelled. His accent is heavy, his speech plodding, his lack of charisma total. "I assumed you would prefer my poor English to my superb German," Karger says dryly. With Karger's oratorical skills, Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart would have been forced to remain honest and monogamous.

Karger, fussing with little multicolored transparencies on an overhead projector, sketches out for his audience an ingenious afterlife that any scientist could love. Where you end up moments after your dinner companions reveal that they never got around to learning the Heimlich maneuver will depend on the otherworldly equivalent of Newton's famous principles. Just as our physical plane is governed by laws, Karger explains, so the ethereal realm is ruled by the "spiritual law of gravity."

Here's how it works: Your spiritual weight is determined by the nature of your earthly preoccupations. "The higher your desires, the lighter your ethereal body becomes," Karger explains. "Every soul is surrounded by souls of the same weight and nature. For some this is heaven, for some, hell.

"The malevolent are with the malevolent -- murderers congregate to mutilate and torment each other, never dying, experiencing only the fury of their passions as both perpetrators and victims."

Neat, huh? Moments later, however, the audience is somewhat taken aback at Karger's choice of spiritual categories: "Gossips with gossips," the bespectacled physicist continues, "smokers with smokers ..."

There is nervous tittering. With Karger's flat delivery, it is difficult to know whether he's joking. Around the auditorium people are left to consider whether it might be worth taking up the habit again just to avoid spending eternity with ex-smokers. And still others contemplate the real implications of Karger's vision -- vast ethereal domains with no occupants and one jampacked spiritual plane full of masturbators.

Karger believes that the hell depicted in the Book of Revelation is not incompatible with what he describes. "Details like fire -- that's one thing that can happen," he insists. "There can be many different pictures, not just the ones we get from Christianity."

"There will be places of great joy, too," Karger says, "for souls who dedicated themselves to the betterment of others."

That would be heaven -- land of clouds, harps and halos. And the next day, ditto. No wonder it was Mephisto's lair that inspired the most memorable visions of Dante. Paradise is not nearly so compelling as speculation about the endless tortures Beelzebub might devise (clouds, harps and halos, for example).

It's instructive that both Greek and biblical mythology started out with fairly benign, if gloomy, underworlds, then gradually moved toward more punitive depictions. Ancient storytellers, the keepers of oral traditions, must have sensed their audiences' need for some kind of ultimate reckoning to redress the imbalances of fate. When hell did not exist, it had to be invented.

It has endured. Mainstream movies like "Ghost" and "What Dreams May Come" can't get away from the idea of a pit for evildoers -- just deserts are the essential flip side of every happy ending. Our collective craving for justice demands an ugly destination for the wicked who appear to prosper without consequences.

But eternal punishment makes for an odd fit with an enlightened credo. "Judge not that ye be not judged," says Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. Secularly, 19th century salon hostess Madame de Stael (allegedly) said, "To understand all is to forgive all."

That compassionate acceptance of human error is probably the most evolved and difficult of spiritual philosophies. And it's a very tough sell on the campaign trail, as any Texas governor can tell you. If you're going to quote Scripture on the stump, better make it the one about the eye-and-tooth exchange. There's always a market for retribution.

Which is why there will always be a hell, at least rhetorically. The physical existence of what the Israelites called Gehenna is beyond earthly proof. But whether or not you believe in it, before the week is out you're likely to nominate a new candidate for membership.

Amen, and pass the brimstone.

Shares