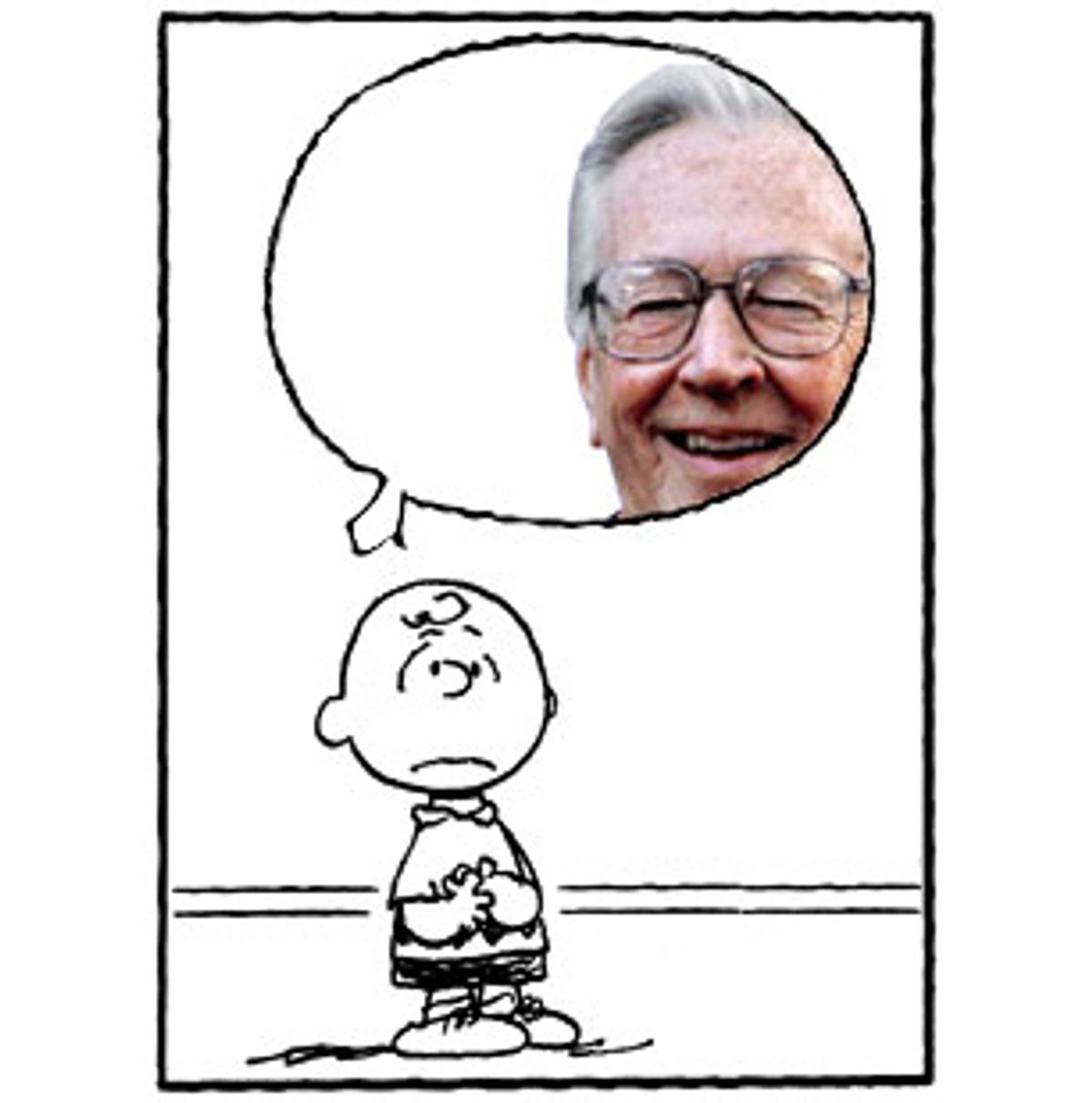

The year is 1995 -- the Red Baron is long dead. Now it's Snoopy vs. the

California Department of Insurance. Metropolitan Life, the insurance

company whose ads feature Charles Schulz's popular "Peanuts" characters, is

in trouble. In her Newsweek column of March 6, 1995, Jane Bryant Quinn

details complaints against MetLife representatives accused of screwing

seniors with shady deals. "In California," she writes, "MetLife cases

are popping up like mushrooms ... A California law firm will soon file a

class action suit against the company." And all the while, Charlie Brown

-- the same round-headed kid who railed against Christmas commercialism

and cradled a pathetic evergreen for successive generations of wide-eyed

children -- grinned out of countless ads bearing the slogan: "Get Met.

It Pays."

It's a problem never faced by the likes of Garry Trudeau and

Bill Watterson. The creators of "Doonesbury" and "Calvin & Hobbes" would not

allow their charges to earn spare cash with endorsements. "I like to

keep my characters on the reservation," Trudeau once said. But if the

MetLife episode embarrassed Schulz, he gave no indication -- "Peanuts"

characters are shilling for MetLife to this day. Schulz may not even

have noticed. The man behind the most influential comic strip in history

has always displayed an unsentimental attitude toward his creations.

Cultural icons they may be, but they're also his living. "I just draw

them," Schulz said recently. "That's all."

And now that's all over. Fifty years after "Peanuts" made its first

appearance in seven newspapers, colon cancer, Parkinson's disease and a

series of strokes have forced the 77-year-old Schulz to retire.

"Peanuts" will bow out with a final color strip on Sunday, Feb. 13.

The daily strip ended Monday with a farewell letter from Schulz.

The Midwestern cartoonist's simple yet evocative drawings do not enjoy

quite the same cultural prominence they held back in 1965 when his first

TV special, "A Charlie Brown Christmas," won an Emmy, becoming as

integral to the season as mandarin oranges (and almost incidentally

establishing Vince Guaraldi's "Linus and Lucy" theme as one of the most

recognizable piano compositions of the 20th century). But never mind --

"Peanuts" changed the cartooning landscape in a way that even the Pulitzer

Prize-winning "Doonesbury" can only envy. Trudeau said as much recently in

a tribute to Schulz written for the Washington Post. "'Peanuts' was the

first (and still the best) post-modern comic strip," Trudeau wrote.

"Everything about it was different. The drawing was graphically austere

but beautifully nuanced ... Although Schulz would say the very notion is

preposterous and grandiose, he completely revolutionized the art form,

deepening it, filling it with possibility, giving permission to all who

followed to write from the heart and intellect."

Actually, "Doonesbury" may well be an exception among today's cartoons, in

that the true spiritual ancestor of Trudeau's strip is not "Peanuts" but

Walt Kelly's brilliantly absurd and sharply political "Pogo." But most

contemporary cartoonists owe a significant debt to Charlie Brown and his

back-stabbing pals. Watterson is now retired. "Calvin & Hobbes," a

pioneering and much-imitated strip in its own right, could arguably be

said to resemble little else but "Peanuts." While nervy, obnoxious young

Calvin was certainly no Charlie Brown, his unsentimental and

sophisticated observations often echoed those of Schulz's ur-loser.

"People who get nostalgic about childhood were obviously never

children," Calvin remarks after a schoolyard beating. In a strip

published over two decades ago, Charlie Brown walks his familiar,

barren suburban sidewalk, jeered at by a succession of passersby.

("Hey Charlie Brown, is that your head or are you hiding behind a

balloon? HA HA HA HA HA!") Arriving home, he boots a radio across the

room after hearing the announcer say, "And what, in all this world,

is more delightful than the gay wonderful laughter of little children?"

Turn to the comics page of today's paper and a couple of things quickly

become apparent. One is the obnoxious calculation behind the many strips

clearly inspired by marketing surveys. The other is how few strips are

actually aimed at children. Today's syndicated features are usually

venues for the same sort of observational adult humor found in sitcoms,

stand-up routines and even novels. And, ironically for a strip in which

adults never appear, it was "Peanuts" that paved the way for the current

emphasis on grown-up themes.

Sophisticated cartooning did not start with "Peanuts." In the early '20s,

George Herriman's "Krazy Kat" was adapted for a ballet. "Pogo" debuted a

year before "Peanuts," and cartooning is unlikely to get any better than

that. But "Pogo" mixed Marx Brothers-style lunacy with politics, and there

was cartooning precedent for both. "Peanuts" was something new. In the 1950s,

readers searching for existential angst usually opted for Salinger --

until the arrival of good ol' Charlie Brown. "[Schulz] did something

entirely different from what the rest of us did," said "Beetle Bailey"/"Hi

and Lois" creator Mort Walker in the Washington Post. "I write and draw

funny pictures and slapstick; it's a joke a day. He delved into the

psyche of children and the fears and the rejections that we all felt as

children."

Charles "Sparky" Schulz was born in Minneapolis in 1922. After serving

time as an infantryman and eventually a staff sergeant in World War II,

Schulz sold his first comic strip to the St. Paul Pioneer Press in 1948,

calling his creation "L'il Folks." United Feature Syndicate picked it up

in 1950 and to Schulz's everlasting horror renamed it "Peanuts." The

first strips did not represent an immediate cartooning revolution.

Still, the tone was established early -- immediately, in fact. "Peanuts"

debuted with a couple of kids on a step watching Charlie Brown go by.

"Good old Charlie Brown," says Patty. "How I hate him!" (As die-hard

"Peanuts" followers know, this Patty was not Peppermint Patty, the fine

athlete/crummy student introduced in 1966. The original Patty seemed to

disappear, along with other secondary figures such as Violet and

Shermy.)

Soon the cast of Schulz's little morality plays became part of the public

consciousness as no other cartoon figures before them -- the hapless

Charlie Brown; the philosophical, blanket-clutching Linus; the

sibling/budget psychiatrist/human pothole Lucy; and, perhaps most popular

of all, Snoopy, the most complex dog in the history of this or any

other creative medium. Although Charlie Brown's fantasy-prone beagle

came to represent the happy face of "Peanuts" (and not surprisingly

provided the easiest entree into the world of marketing, where "Peanuts"

characters are now said to generate a billion dollars annually), the

Snoopy of the daily comic strips is not just the carefree, dancing soul

seen in the TV specials. He is in many ways a more fully rounded

version of Charlie Brown, capable of the same nihilistic observations

about our place in the cold universe but, unlike his master, also blessed

with a little joie de vivre. And the perspective of a dog. "They always

act like they're doing you such a big favor," he mused, preparing to

catch an airborne morsel of hot dog.

"Peanuts" characters became worldwide symbols of America on par with

Mickey Mouse. (Note that the Knott's Berry Farm theme park hired them to

compete with Disneyland just down the road.) Unlike the born-to-be-sold

Mickey, though, the commercial overkill surrounding "Peanuts" is in

marked contrast to the simple, almost austere spirit of the source

material.

Among Schulz's most notable achievements may have been the thoughtful

Christian spirituality he injected into the strips on a regular basis,

sometimes overtly and sometimes, as Robert Short pointed out in his 1966

book "The Gospel According to Peanuts," by simply mirroring Scripture

indirectly. It was no accident. "I liked Biblical things," Schulz

recently told Newsweek. He has often spoken of his deep religious faith

but, not surprisingly, it is a faith tinged with realism. "Once you

accept Jesus," Schulz wrote in Decision magazine in 1963, "it doesn't

mean that all your problems are automatically solved."

Charlie Brown and Linus would occasionally sit on the couch poring over

some Bible verse that would be punctuated by an afterthought from

Snoopy. Thanks to his unassailable position in the cultural mainstream,

Schulz could afford to display a gentle irreverence to Scripture that

might have gotten another artist into trouble. (As it was, Schulz told

Newsweek that the only serious editorial complaint lodged against him

came when he introduced the character of Franklin who, depending on your

point of view, either integrated the strip or ruined the neighborhood.)

Schulz's spiritual curiosity is the sort that can be appreciated even by

nonbelievers. It stands in stark contrast to the increasingly

heavy-handed pulpit pounding of Johnny Hart, creator of the long-running

strip "B.C." Schulz's characters ask questions about God. Hart's spout answers.

The "Peanuts" gang did not age (at least not since the earliest strips,

when they appeared to be much younger), but they did change. Charlie

Brown's battles with failure and despair never ceased, but in later

years he was less often the target of overt hostility. Chuck was even

the object of crushes held by Peppermint Patty and her androgynous pal

Marcie, and although he never obtained his heart's desire -- the Little

Red Haired Girl -- Charlie Brown had something like a genuine fling at

camp with a girl named Peggy Jean. He also learned to dance.

Like an adult who has left behind the blatant cruelty and hostility of

childhood but still bears the scars, Charlie Brown lies awake at night

and asks questions of the void. The "Peanuts" reader always knows whose

questions they are. "Everything I am is in that strip," Schulz said

recently.

Schulz paid a price for flogging his little wards so mercilessly. The following

conversation happened in a

coffee shop recently:

"Charles Schulz is finally retiring."

"The 'Peanuts' guy? Gawd, I thought he was dead!"

The strip's daily appearance in the paper evidently wasn't enough to

convince this young woman that Schulz was still above ground. Some of

the blame for that must surely fall to the excessive marketing that

turned his original winsome creations into a monolithic commercial

franchise. And if little children look skyward at the Macy's parade and

see only the giant inflatable effigy of an insurance salesman, that's a

shame. But in no way does it diminish the accomplishment of Charles Schulz.

In retirement he leaves behind an important example. "All right,"

Charlie Brown says after once more receiving assurances from Lucy that

she will not pull away the football just before he can kick it. "I'll

trust you. I have an undying faith in human nature. I believe that

people who want to change can do so, and I believe that they should be

given a chance to prove themselves."

Moments later he is, of course, flat on his back. Lucy stands over him,

holding the unkicked ball. "Charlie Brown," she says, "your faith in

human nature is an inspiration to all young people."

Shares