"Ever seen dogs treated as art supplies?" William Wegman moves a Weimaraner across a platform as if the creature were an 80-pound barrel of gesso. The art supply in question, Chundo, a 10-year-old male and son of Fay Ray, endures the process with a matter-of-factness, never dropping his straight-ahead stare as the photographer pushes him four inches to the left so that he and another dog, Chip, sit shoulder to shoulder.

"Don't tell anyone how easy this is," Wegman says.

He walks back to the camera -- a $30,000 digital Hasselblad he just started renting by the hour. The equipment's still new to him -- he repeatedly fails to locate the trigger-release cord, the thing you squeeze to shoot a picture -- but he doesn't seem to mind. He squeezes and 10 seconds later an image pops up on a computer monitor. He peeks over at it. Grappling with unfamiliar machines is nothing new for Wegman. Indeed, several times in his career -- most famously in 1978, when, at the invitation of Polaroid, he began photographing his first dog, Man Ray, with a large-format Polaroid camera -- his experiments with new technology led to new ways of seeing, reinvigorated the way he worked, and helped introduce him to a wider audience. Once he's studied the image on the monitor, he and the rest of his studio crew return to the platform for some more rearranging.

"I'm pretending I help," he says, then begins to write this piece for me: "Unlike some photographers who make their assistants do all the work, Wegman actually gets down on this hands and knees ..." Actually, by this point, he's standing. The assistants continue with their tasks as he keeps up his soft-spoken deadpan.

The excitement in the room can't be attributed entirely to a fresh technical challenge. There are also puppies who are sitting for their first portraits before handlers take them to the vet. One remains behind, venturing onto the platform without being asked, taking a place beside Chip and Chundo, apparently eager to work. The trio blend together nicely. The professional calm of the practiced models seems to rub off on the first timer -- until there's a noise at the door and all three dogs stand and bark at once. Wegman squeezes.

When the session is over, he puts his sneakers back on and walks out of the studio and back up the stairs of the former schoolhouse he now calls home. The dogs rush to follow, their nails clicking on the cement as they scurry by him.

Conversations about real estate in New York often function as a sort of shorthand biography. By this measure, Wegman has led a fascinating life since 1973, when he moved to the city at the age of 30. His first sublet, on 27th Street, was so dingy and uninspiring that he instead chose to camp out in an abandoned factory in East Hampton. (The factory office, with its authentically bad '70s paneling, is the location for the video "Spelling Lesson," in which Wegman patiently explains Man Ray's spelling mistakes as the loyal dog listens.) By 1978, he and his wife Gayle Lewis occupied two floors of a Tribeca loft -- until a fire destroyed the place (along with his paintings, photographs and negatives). In 1982, he moved into a former synagogue in the East Village. In 1997, he bought the Chelsea schoolhouse where he now lives with his third wife, Christine Burgin, their two children and his current brace of Weimaraners.

It's tempting to match each address with a stage in the artist's career: fame, flameout, regeneration, maturity. But the bricks-and-mortar chronology doesn't account for Wegman's gentle Arcadian irony, which has its sources in other real estate. Wegman was born in Holyoke, Mass., in 1943, and he grew up in nearby Eastern Long Meadow, a small town marked by the ponds, fields and dirt roads of unimproved baby-boom suburbia. His father, George, worked in the local Absorbine factory, but the job was not a fair index of the family's comfort or status: Longmeadow was a fancy enclave and the Wegmans regularly vacationed with the factory's owner. Many children of the '50s describe their parents as Ozzie and Harriet types, but when Wegman does so, there's no hint of post-therapy resentment. He makes it sound like both an understatement and a compliment.

As is often the case with Wegman, underneath this gentle layer lies another gentle layer. His father, a "sweet and easygoing man" and the youngest of seven brothers, began working for Absorpine at the age of 16 after his own father died in an automobile accident: The family decided that the younger sons would work to support the clan while the older brothers went off to college. Apparently, the arrangement worked. A photograph that Wegman took in 1984 shows the brothers, safely landed in their sunset years, silver-haired, in a variety of horrendous plaid slacks, Bermuda shorts, golf shirts, white socks. None of them face the camera, but instead direct their attention to each other -- each seems to be in the middle of telling a different joke. They are also in on the joke Wegman is making -- it seems clear they enjoy indulging Billy the Artist. An air of amiable foolishness stretches from generation to generation.

You can see it popping up in many stories of Wegman's life. For instance, that he almost didn't attend the Massachusetts College of Art because it didn't have a hockey team. It's a good story, and seemingly every account about his apprenticeship (in painting, followed by a post-grad about-face to photography and video) is introduced by this anecdote. Wegman clearly doesn't mind the prominence given to this moment of indecision. In fact, the mismatch he conjures (art vs. ice hockey) is just the sort of unequal pairing his art is filled with. His videos could just as easily appear in an exhibition of conceptual art or on "Saturday Night Live," and the dog photographs recall both surrealist Marcel Duchamp and the 18th century horse paintings of George Stubbs. Unlike Cartier-Bresson, who championed the decisive moment in photography, Wegman carefully concocts the indecisive one.

The eureka moment came like this: He was talking on the phone, drawing little circles on his hand. This was 1970, in Madison, Wis., where he'd gone to teach conceptual art and photography, after he'd realized that painting was dead. (He wasn't the only one to do so in the '60s.) After the phone call, he went to a party; here was food, he reached for a slice of cotto salami -- Bingo! The cut peppercorns matched the doodles, which matched the gemstones in a ring he wore. He remembers how pretty it was. The coincidence of circles made his hand look like meat, and the whole setup looked somehow like outer space. "It had that kind of strange beauty," he says. "And so I set it up and the photo came out amazing. And I never took a photograph like that, that was so graphically strong. It cleared my mind."

It was the heyday of conceptual art, when it seemed that every article by or about Robert Smithson began with a quote from Wittgenstein or Merleau-Ponty or the Third Law of Thermodynamics. Wegman felt a little worn out, he says, from studying set theory, logic, mathematics, philosophy, all the heavy lifting that went with the pose. "I wanted to be smart and superior and know everything," he says, "but I just wasn't cut out for it." "Cotto" made him forget about the conceptual strategies he'd been experimenting with -- documenting performances or creating such Smithson-like environmental events as floating a line of Styrofoam cups down the Milwaukee River.

A year later he moved out to Los Angeles, the headquarters of the droller branch of conceptual art. Wegman remembers being compelled by funny, strange work like Bruce Nauman's -- the holograms of the inside of his own mouth or the videos where he played a violin very badly while standing in the corner of a room. As he describes such influences -- Nauman, Allen Ruppersberg, Ed Ruscha -- his tone is measured, respectful, sort of Wall Street Journal meets Artforum. He really lets go when I ask about his favorite comedians. "My heroes were always Bob and Ray," he says, recalling the Boston radio team of Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding, who did dry, Down East bits, describing summer vacation photos on air or running spelling bees where one contestant gets "interfenestration" and the other gets "who." Wegman gushed about them -- their minimalist approach, how they could be so funny with so little. "They were kind of lazy, too. They didn't try very hard, it seemed," he says. "But you can't if you're going to be funny."

Wegman's videos -- his contribution to the conceptual canon -- combine these approaches. He's a combiner by nature (Can't walk along a river without a fishing rod, he explains, because "just to take a walk in the woods isn't interesting, but to pursue trout!?"), so when Man Ray, the Weimaraner he got in his first months in L.A., kept barging into the videos he was making, he decided to go with it. Wegman compares this offhand video work to drawing -- sketch comedy, as it were -- and Man Ray fits perfectly into the mood of straight-faced ludicrousness. In one, Wegman, on his hands and knees, backs across the floor, and the dog follows, licking off the line of milk that Wegman spits out onto the tiles.

Although he lived on food stamps for a year before people started to pay attention to his photographs and videos, by the mid-'70s Wegman's work began receiving both critical and popular acclaim -- he was picked up by the Sonnabend Gallery, which gave him one-man shows in both its Paris and New York branches, and his videos appeared frequently as short spots on "Saturday Night Live." But the fame that elevated him also tended to reduce his body of work to its most obvious element: the dog. By the late '70s, he observed, he felt "nailed to the dog cross," a bit of hyperbole that hid other problems endemic to many postmodern art stars -- drink, drugs and grumpiness. For a year, he swore off work with Man Ray. "I became sort of a strange, sad, lonely, hibernating sort of person who was antisocial and just wanted to make my own drawings and little crazy pictures. And everyone excused me for that because, of course, I was an artist and I was supposed to be crazy and reclusive," he said. "But I wasn't happy."

About the time that Wegman lost everything in the loft fire, in 1978, Man Ray contracted prostate cancer and fell into a coma; the vet recommended putting him down. But Wegman chose to keep him on strong antibiotics and the dog survived. And despite an initial reluctance to make more Man Ray photographs, Wegman recognized the power of the 20-by-24 Polaroid poses he was invited to take that summer. "My approach to color and beauty and elegance and all those things that were formerly dirty words, that weren't allowed in my manifesto, that I didn't want anything to do with -- suddenly they were blasted right back at me in a stunning way." Again the dog pointed the way to greater fame. By the time Man Ray died, four years later in 1982, the Polaroids had made them both so widely beloved that the Village Voice named the dog "Man of the Year."

The New York art world is a tiny town. Gossip travels fast, as if the whole place were on the same party line. It's not hard to come up with items concerning Wegman and women. The public record notes three marriages, to Gayle Lewis (divorced 1978), to Laurie Jewell (divorced 1982) and to Christine Burgin (current). In between there were girlfriends. You could say he has a doggy nature. But, as we sit in the painting studio that his kids have taken over -- a tumble of cardboard boxes from an impromptu presentation of "The Nutcracker" litter the floor -- he seems happy. In the hallways, there are giant Polaroids of his children, Lola and Atlas. Wegman explains how he let the boy hold the trigger-release and take the picture. That is how he got him to look like that, intent, staring straight at the camera.

After Man Ray's death, Wegman concentrated on other mediums: drawings, one-sitting short stories with odd endings ("They sort of came out of the typewriter," he explains) and, again despite his manifesto, painting. The paintings are the redheaded stepchild of the Wegman oeuvre -- largely neglected, they travel from gallery to gallery, while the rest of his work steals all the attention. They're as eerie and difficult as the photographs are pleasing and immediate. Still, I get the sense that he prefers their company. Several of them lean against the wall in the studio/playroom -- he has cited wallpaper as an influence, especially the out-of-register kind, like the pirate wallpaper in his childhood bedroom. The most wallpapery one of all has a blue background; planes, boats and seagulls float on it. As Wegman talks about his own childhood, how he didn't meet his father until he was 2 (George Wegman's B-17 was shot down, and he was kept in a German POW camp until the Liberation in 1945), I get a quick glimpse into the pull of the haunting and simple painting. I believe Wegman when, a few moments later, he claims that he has shaken off what he learned in art school, that he now paints the things that inspired him before he learned what art was and wasn't, when he was 3 and 4.

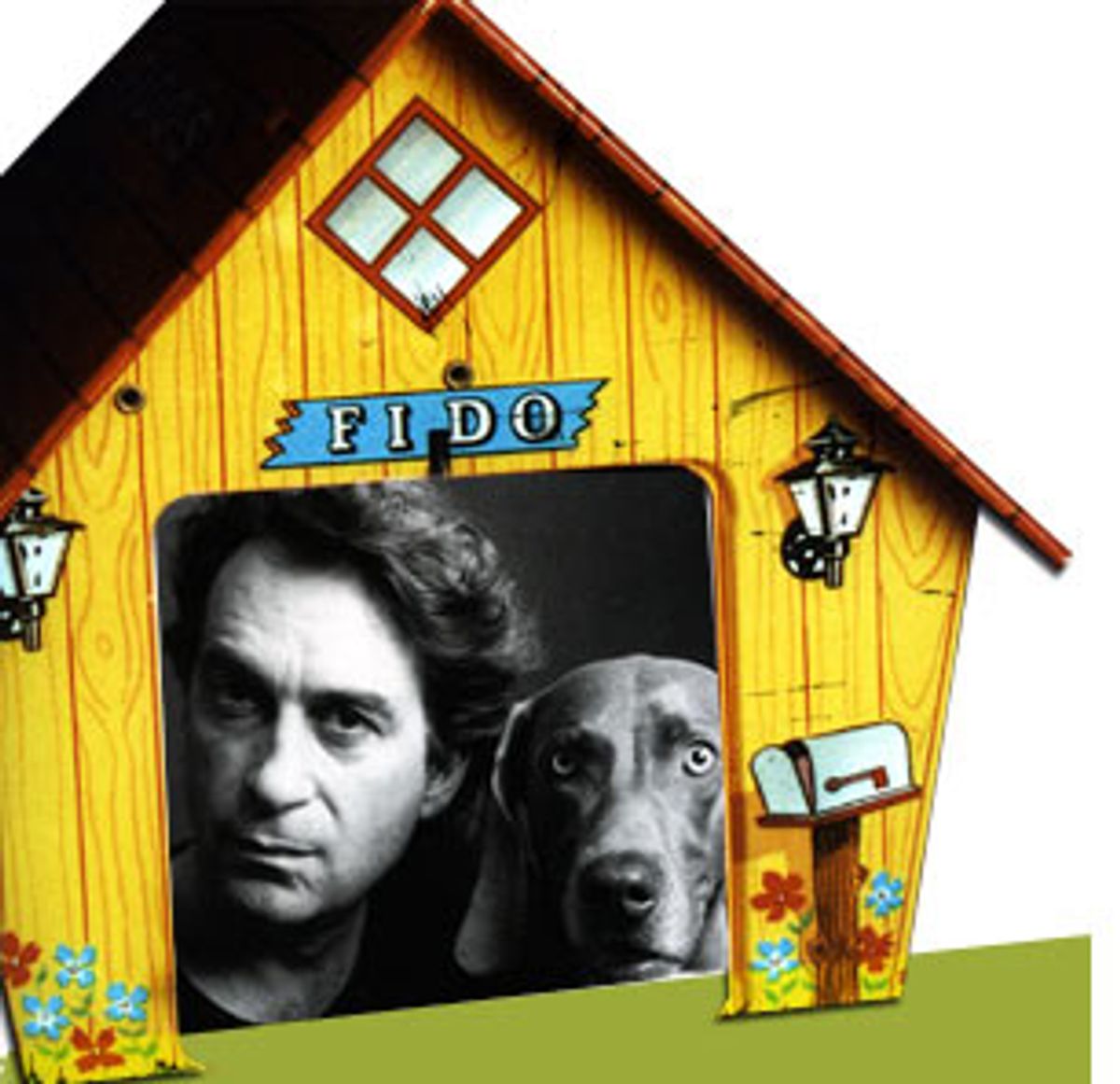

Three years after the death of Man Ray, Wegman was happily absorbed in this sort of painting. The one thing he didn't want was another dog. But in 1985, he visited a litter of puppies and fell in love with a cinnamon one he called Fay Ray, so he revised his sentiment to a vow not to photograph her. In retrospect, there is something Jack-in-the-Beanstalky about all of these demurrals, as if Wegman were ready to throw the magic beans out the back window. But this time there was a new ending to the fairy tale. In 1978, when Wegman tried to prove to himself "that I could exist as an artist without relying on my dog," he changed course when he saw that Man Ray wasn't happy being exiled from the important part of his life. But with Fay Ray, Wegman admits, he learned that he wasn't happy until he was photographing her. "As long as I had the dog and the camera," he says. "It makes for a kind of compatibility I found really, really important."

And rewarding. Fay Ray, he noticed, had a chameleon quality that differed from Man Ray's solid presence. He found new balances for Fay ("the helix, the narrows, the standing look-back"). Some of the postures suggested costumes, human clothes and characters, and he managed the effect so well that "Sesame Street" hired him to create educational doggy videos. After Fay mated with Arco Laudenburg von Reiteralm and had a litter of 10 in 1989, Wegman began spotting (or imputing, depending on your take on the mysteries of anthropomorphism) character traits in Fay's puppies. The current Weimaraner juggernaut, with its various divisions in publishing, television, video, commercials, posters, postcards and refrigerator magnets, was born.

He is a little ambivalent about the side effects. On the one hand: "Thank God! So many people have Weimaraners now, I'm not even recognized anymore when I walk with the dogs. They don't even ask me." On the other hand, Wegman feels responsible, if this popularity means that natural hunting dogs get cooped up in an apartment. Other owners, who perhaps don't have the time or resources to employ a crew of 21 to film their dogs dressed up as lady detectives, wonder why their puppies aren't as gentle, sweet and calm as his. "They kind of help each other," he explains. "Remember when Chundo was up there and the puppy came up? Because he wanted to be there. That's very sweet, I thought. I didn't ask him to be there but he wanted to go up and be there."

There is a practical side to Wegman's devotion to his dogs that is almost Old Masterish, like Chardin taking the time to make his own paints. But he has also tapped into something much more mysterious, in the presence of which Wegman is endearingly sweet and modest. "I don't feel lonely when I'm around them," he says. "But I love also listening to them. I always make sure I spend some time just seeing what they're really doing. Especially outside, you know, when you're alone with them. Because so many people including myself fill in a whole vocabulary for them that is ours and not theirs. I remember spending some time for the first time with Man Ray, my first dog. I didn't talk that day. I just listened to what he was listening to, the whole aura of smells and sounds and sights and things that he was picking up on during that day. Most people who have dogs see them as their dogs: 'Come on, boy,' or 'Fetch' or pat, pat. But they're really teeming with their own thoughts."

Shares