Has anyone of our time produced grander poetic gestures than has Christo? The trademark of his work -- swathing landmarks like the Pont Neuf and the Reichstag in fabric, or wrapping 1 million square feet of coastline in Little Bay, Australia; erecting a fence of white nylon through 24 miles of California's Sonoma and Marin counties; surrounding 11 islands in Miami's Biscayne Bay with hot pink material -- is majestic delicacy. That Christo's art has somehow retained lyricism is all the more remarkable when considering the physical logistics and particularly the bureaucratic barriers he has to overcome before realizing them.

Even though the costs of his projects run routinely into the millions, funding them is one of his easier tasks. Among the world's best-selling artists, Christo obtains the money for each new project through the sale of the models, collages and drawings he makes. The real headache is the lobbying Christo must do to obtain permission from authorities. The "Surrounded Islands" project in Biscayne Bay required the permission of seven different federal and state agencies. The "Running Fence" for Sonoma and Marin counties necessitated not only permission from authorities but from each landowner whose property the work would pass through.

Twenty-four years separated the proposal and the realization of Christo's 1995 wrapping of the Reichstag. Plans to erect 15-foot-tall gates of fabric over every pathway in Central Park, and to build a pyramid of 390,500 oil barrels in Abu Dhabi, have been pending for almost 20 years now.

And then there's the "huh?" factor. Christo has long been a convenient punch line for people who see modern art as a joke, as "something my kid could do." Since public approval is a crucial element in determining the fate of Christo's proposals, it's necessary for him to confront and overcome that kind of thinking. Let's face it, there is something loopy about the impulse to swathe large public edifices in nylon or polypropylene. The five documentaries that the filmmakers Albert and David Maysles -- best know for their documentary films "Grey Gardens" and "Gimme Shelter" -- (and their various collaborators) made about the progress of Christo's work are full of the comedy inherent in the collision between the avant-garde and everyday life. Imagine, you're taking some time out from your day, having coffee with friends, when you're approached by a slim, intense man with scruffy hair and horn-rimmed glasses who says, "Hello, my name is Christo and I want to wrap the Pont Neuf in silky fabric for 14 days."

But the Maysles' films (the best record of Christo's work and for those of us who haven't been lucky enough to travel to his installations, the best way to experience it) are also full of the unexpected beauty of these unlikely encounters. Addressing one of the numerous civic boards he must approach to obtain permission, Christo tells the assembled supporters and detractors that no matter how they feel about it, they are all a part of his project. Figuratively and literally, Christo works in the public sphere, and his proposals become tabula rasas upon which people can project the best or the worst of themselves. That he has so often succeeded in converting people to seeing the beauty in what he proposes speaks to the democratizing principle that guides his work.

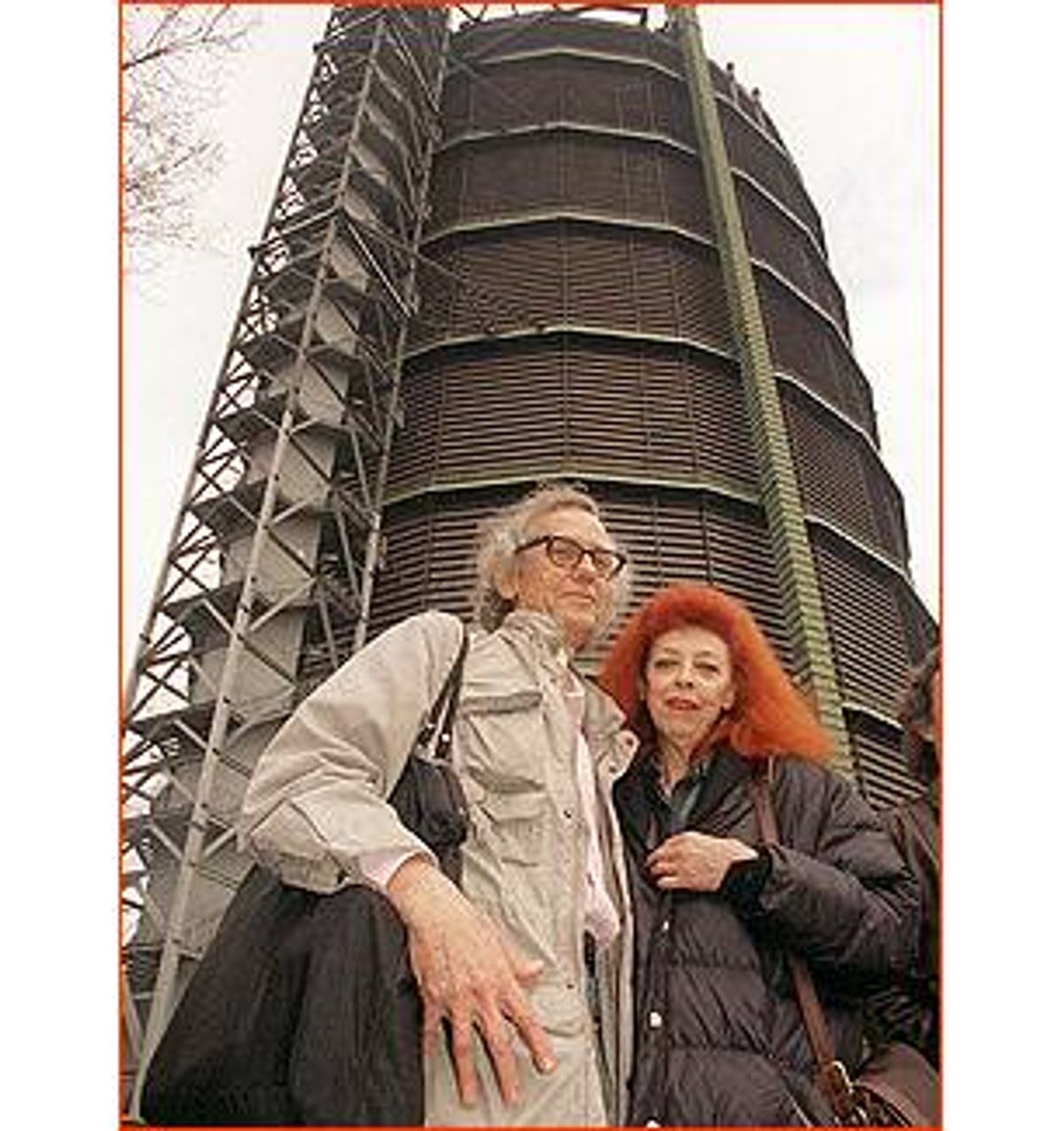

That principle has grown more expansive with the scale of Christo's work. His first wrappings -- cans and bottles and packages -- combine the cheek of Marcel Duchamp's "readymades" (everyday objects offered as art) with a Warholian awareness of art as packaged commodity. But Christo and his French wife and manager Jeanne-Claude, who now cosigns his work, have said, "All our work is about freedom," fitting for an artist who escaped from his native Bulgaria in the mid-'50s when the uprising in Hungary sent tremors through the Soviet Eastern Bloc.

In her monograph on the artist, Marina Vaizey argued that Christo's wrapping technique is a direct response to his experience as an art student trained during the period of what he has called "High Stalinism." In one of the Maysles films we see a photo of the young Christo as a student in a state art class engaged in sketching an old gentleman. Allowing for the differences in the angles from which the students view their model, every drawing looks the same.

It's a startling example of how realism can be used to conceal. After growing up under an aesthetic that dictated that how things look is how they really are, what could be more subversive than revealing by covering up, blotting out details in order to more fully grasp the entirety? Christo's response to the Berlin Wall was to barricade a narrow street in Paris (where he was living) with 240 oil barrels in a structure he called "Iron Curtain." For years Christo's unrealized dream project was the wrapping of the Reichstag, which he finally achieved in 1995. Undoubtedly one of his greatest successes, it would have had even greater symbolic import in the years before reunification, when the dismantling of the Berlin Wall barely existed as a fantasy. Had it occurred then, East and West Germans would have simultaneously been able to see the former home of the German Parliament standing like a ghost among them.

But in most of Christo's work, the explicitly political is submerged by the aesthetic. His borders and fences and walls, Vaizey points out, are about transcending the barriers between life and art "although both are still clearly defined." Certainly, the story of Christo and Jeanne-Claude's romance is what you might expect from a maker of such romantic gestures. The daughter of a respected French general, Jeanne-Claude met Christo when her mother, who had seen his drawings displayed at her hairdresser's, brought him home for lunch. The two were immediately attracted to each other, but Jeanne-Claude went ahead with her planned marriage to a young officer, exactly the type a girl of her station would be expected to marry. It lasted three weeks before she left him to move in with Christo. (When you toss in the fact that they were born on the same day and the same year, the love affair sounds like kismet.)

Taken together, the five Maysles documentaries -- "Christo's Valley Curtain," "Running Fence," "Islands," "Christo in Paris" and "Umbrellas" -- are a portrait of their marriage, which, from all appearances, looks to be a volatile, sometimes squabbling and altogether rock-solid union. She is fiercely protective of him, and he, proud and defensive, is sometimes resentful when she advises him on how to approach someone. Anyone cursed with a temper will immediately recognize Christo as a brother. After all the years of working his way through the bureaucratic impediments to his work, he is still flummoxed that people can be so suspicious or dense. Addressing large groups, he tends to wax philosophical on the nature of his art when he needs to be more plainspoken and direct. He's not a schmoozer. When he's advised that he should try to charm Jacques Chirac (then the mayor of Paris and terribly concerned with retaining the public's approval) to obtain his support for the Pont Neuf project, he looks as if he's been asked to put on a bunny suit for Easter.

Given glimpses of what Christo and Jeanne-Claude are up against, you can scarcely blame his anger. You could understand the bureaucratic opposition if leaders were merely expressing qualms that the project would wind up costing the city or state money, or if the projects would permanently alter the landscape. But given the readiness with which the Christos refute those reservations (for instance, an environmental study for "Surrounded Islands" in Biscayne Bay showed it posed no danger to the plant or marine life), it's fair to assume that something else is going on.

The drama of Christo's lobbying for approval is one that prefigured the government battles over art that have erupted periodically over the last 10 years. His work isn't confrontational or shocking. Nonetheless Christo is facing down nothing less than a deep suspicion of art itself, a fear of what's different and a suspicion of Christo himself as a foreigner. (Having lived in the United States since 1964, he is an American citizen.) The remarkable thing about the behavior the Maysles capture on camera is that Christo's opponents don't seem to realize how fully they give away their prejudices.

By far the sleaziest of their opponents is a Miami councilman named Harvey Ruvin, one of the most opportunistic hustlers it will ever be your amazement to watch in action. Ruvin tries to couch his objections to the "Surrounded Islands" project in civic pride, saying he can't help feeling there's something "chauvinistic" about Christo's proposed use of the islands in Biscayne Bay. He reveals his real agenda soon enough when he tells one of Christo's advisors that some monetary "flow back to the resource" will ensure his yes vote. When the advisor balks, Ruvin drops the public-servant lingo altogether. "Ever hear the phrase 'payback's a bitch'?" he asks. Ruvin finally accepted Christo's offer to donate 1,000 signed posters that the city could sell, but what astonishes you as you watch his naked grasping is how fully he revealed himself.

Why would any artist put up with that? The answer is that time and time again Christo's work has the uncanny ability to sweep ordinary people who have never given a thought about the place of art in their lives into its spell. It's profoundly moving to see people discovering a capacity to respond to beauty that they may never have suspected they had in them.

A diner waitress looks at the skeleton of the "Running Fence" and marvels that it allows her to see the contours of the land. One of the ranchers whose land it passes through takes some buddies to see the completed fence so they can admire how solidly it's constructed and suddenly blurts out that he thinks he'll come out and sleep by it that night. Most eloquent of all is a construction worker who helped hang the "Valley Curtain," a flutter of orange fabric stretching across Colorado's Rifle Gap. He talks about the curtain as an amazing feat of engineering, but as he speaks his eloquence comes not from the words but from the feeling in them, the determination to describe a sight the likes of which he's never seen. He talks about the erection of the curtain as a democratic process, something you have to want to be part of, an accomplishment that needs something beyond attitude, something akin to faith. Asked if he was skeptical that the curtain was possible, he responds by asking how it's possible to be skeptical in a world where you have the Golden Gate Bridge or the Empire State Building. And then he stops, realizing those comparisons can't suffice, and he just says, "This is a vision."

And that, I think, is why Christo works in the public sphere. By taking his art, from planning to execution, out of the privacy of the studio and the cloistered museum, Christo is making art accessible to people in a way it may never have been for them. Ironically, the most succinct definition of what he does comes in "Christo in Paris" (the film about the Pont Neuf project), when one of Christo's detractors says that art is "a creation of the mind that transforms reality."

The easiest way to describe the "Running Fence" or the "Valley Curtain" or Pont Neuf is as a tuning fork for nature. There's historical significance in Christo's choice of gold polypropylene to cover the Pont Neuf -- it was the color of the sandstone of old Paris. But the color also catches the spangled reflection of the Seine; it glows in the sun and becomes a burnished red at sunset. And it's not just the color that changes. Wrapped in fabric, the details of the bridge disappear, but the structure becomes intimately apparent.

In "Christo in Paris," watching a sheet of the golden fabric sliding down one of the pillars of the Pont Neuf, my initial impulse was to look away, as if I were seeing a lady roll down her stockings in public. And as this "second skin" envelops it, the shape of the bridge billows and changes in the breeze, making it susceptible to natural law. Is it natural? No, there's nothing natural about surrounding the islands of Biscayne Bay with hot pink fabric. But then art isn't natural. And yet the fabric emphasizes the shape of the islands and their relationship to one another; seen from above, they form a snaky chain through the bay. For the people living in Miami at the time, or for those who passed over the Pont Neuf on foot daily, Christo's wrappings made them take notice of what they might otherwise take for granted, allowing them to see the "art" in their everyday lives. Even the clanging of the cable against the steel poles of the "Running Fence" served a purpose, sounding a whistling echo that suggests the vastness of the Sonoma and Marin valleys. Nearly all the Maysles films end the same way, in near silence with the camera seemingly as awestruck as the participants and onlookers, drinking in the vision that has materialized before them.

Given the way Christo's work connects art to nature, and given his faith that people will want to take part in it, the disaster that befell the 1991 "Umbrellas" project was particularly cruel. The project, which opened simultaneously in Japan and California, consisted of thousands of large umbrellas (yellow in California and blue in Japan) dotting the landscape. It was troubled from the start. A typhoon that hit Japan shortly after the project opened necessitated closing the umbrellas temporarily. The typhoon passed, but several days later in California, Lori Keevil-Matthews, a spectator, was crushed to death when a freak windstorm uprooted an umbrella and pinned her against a boulder. Christo immediately ordered the project closed. (The umbrellas had been tested in a wind tunnel to withstand gales of up to 65 miles per hour. In the Maysles film of the project you can actually see the enormous dark storm cloud descending into Tejon Pass.) While the project was being taken down in Japan, a worker named Masaaki Nakamura was electrocuted when the crane he was on touched a power line.

These deaths were the darkest examples of how much Christo's art is grounded in the real world. After the deaths there was much speculation about whether he would ever again be able to gain permission for his work. So it was a surprise when, four years later, he got the go-ahead to wrap the Reichstag. It seems foolish to some people that projects that involved so much time, energy and money are temporary. But they have to be if they are to have any meaning. Gazing at the wrapped Pont Neuf, one young man in "Christo in Paris" wishes it could stay that way forever. If it did, though, it might soon be as taken for granted as the bridge was before the wrapping, as some of our greatest artworks are, simply because there is no doubt they will always be there.

It takes some courage to admit that works of art are finite. Some of the largest of painter Anselm Keifer's canvases may only be around for another generation or so because the natural elements he incorporates into them -- twigs and grass and leaves -- are decaying. We have already had the somewhat comical spectacle of restorers gluing cigarette butts back onto Jackson Pollack's canvases. But the temporary lifespan of Christo's projects, and the fact that they are subject to the ravages of nature, is a way of emphasizing that art is not just objects, but a means of affecting emotion and thought. Perhaps the knowledge that Christo's art is temporary sharpens our perceptions, in the same way they're sharpened when we're storing our sense memory of places we're not likely to return to.

None of the Maysles films show the installations being dismantled; that would be too sad. And though the history of each project is documented in lavish books (the hardcover pressings of the Pont Neuf book contain a swatch of the fabric used to wrap it), movies seem the truest way to preserve the ephemeral nature of Christo's art. Photos can capture only bits of the ever-changing installations. Film, the most transitory art form, being nothing more than shadows and light projected on a screen, is able to show the transforming effect of the elements on the works. Since movies don't exist the ways books or paintings do, because they are there and not there at the same time, what we take away from the Maysles films is the experience of, for a short time, being able to see them, the same experience of the spectators of the "Running Fence" or the Pont Neuf or the wrapped Reichstag. I said that Christo's projects were gestures, and they are, with everything fleeting that word implies. There's no reason the experience of them need be fleeting. Being able to say you brought some grace to the world seems to me about as good a legacy as any artist could ask for.

Shares