Roughly 10 points is all it took for the Beast to rise. Until this moment, the Champions Senior Tennis Tournament in Central Park's Wollman Rink had been a sweet chance for tennis fans to revel in nostalgia. Here was Jimmy Connors at 47, mock-limping to the delight of the capacity crowd of 3,000. There was the once-stoic Swede, Bjorn Borg, 44, actually laughing between points at Connors' antics. All grown-up now, they parodied the solemnity of a youthful rivalry. They had realized, finally, that it was only a game.

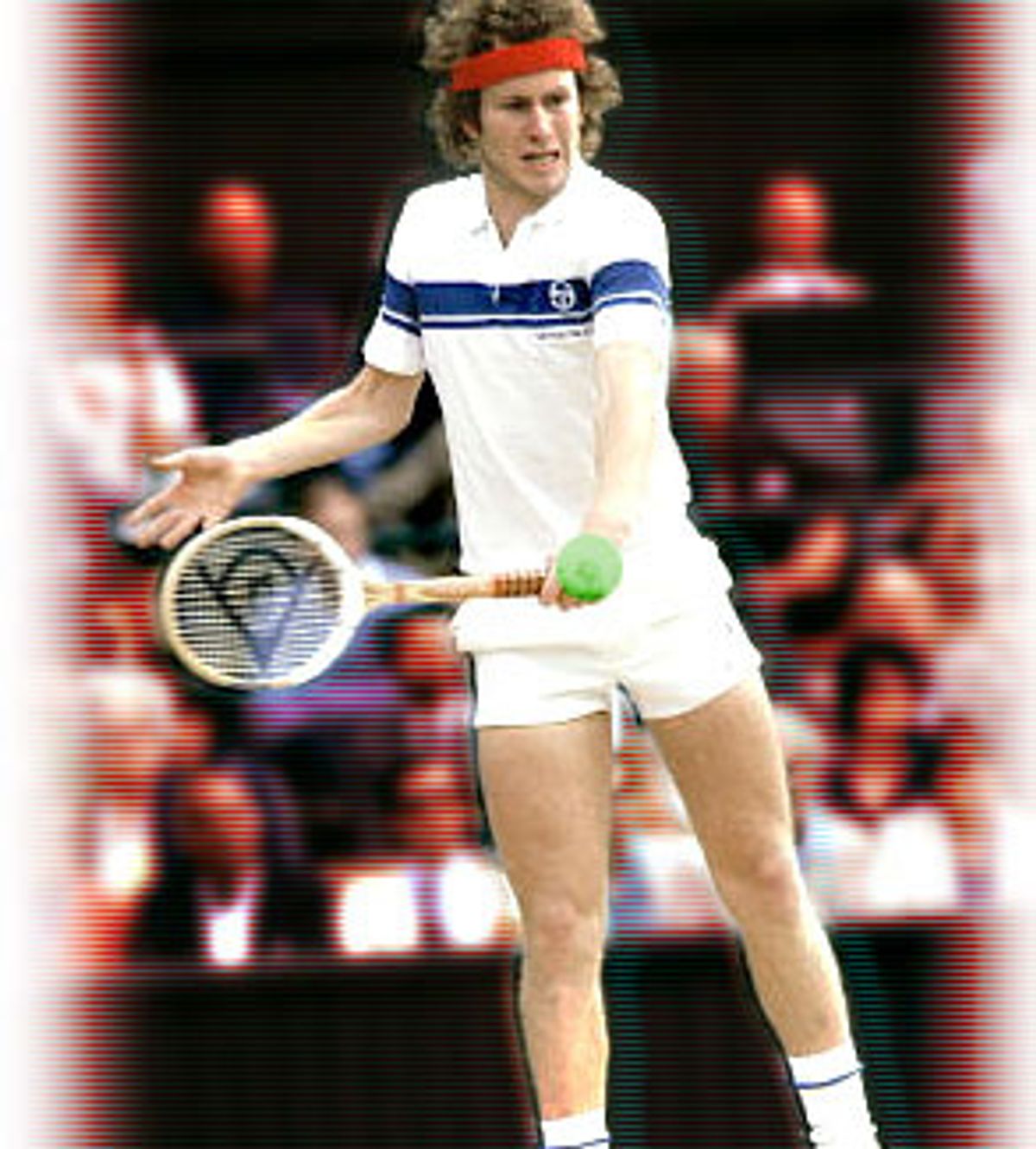

All except, that is, for the Beast. Friday night, June 16, should have been Johnny Mac night in New York City. The legendary John McEnroe had walked to the court from his Central Park apartment, Yankees cap pulled down tight. As so often happened throughout his playing days, he had been greeted by enthusiastic cheers from his hometown crowd. Yet a mere 10 points into his match against Frenchman Henri LeConte, there was the graying, 41-year-old McEnroe, a doting father of five plus a stepdaughter, doing something just as inevitable: Turning everyone against him by charging the net -- to question a lines call. "C'mon, Mac, not already!" a spectator called out.

McEnroe turned to the courtside fan, his face suddenly pale with rage. "You got an appointment to get to?" he said, spitting out the words through lips pursed in anger. "What the fuck do you care, asshole?"

The crowd erupted in boos and the umpire administered a code violation for unsportsmanlike conduct, but it was too late: The Beast had been unleashed. For the next two hours, against all his intentions, McEnroe stalked the court, throwing his racket four times, berating a middle-aged linesman and slamming a courtside sign advertising Sector Sport Watches ("Hey! Hit somebody else's sign!" someone yelled from the Sector Sport Watch company box seats) in dangerous proximity to a female tournament official, whom McEnroe then blistered with a series of choice condemnations of the "you fucking asshole" variety when she saw to it that he be penalized. He also, in between such dramatic acts, hit some of the purest and most creative shots a tennis court has ever seen and, once the match was over, refused to shake the umpire's hand, leaving a crowd that came expecting feel-good nostalgia but instead had been treated to the genuine, raw article.

Screw nostalgia, McEnroe seemed to say; just as in the '80s, when his combination of talent and temperament transcended his sport and he attained pop-culture icon status by turning tennis into performance art, McEnroe had yet again provided a voyeuristic glimpse into tortured genius.

It is no accident, after all, that since leaving the tennis tour in 1992, McEnroe has devoted himself to rock music -- writing and performing songs in New York clubs under the moniker the Johnny Smyth Band -- and opened a SoHo art gallery. He has always delighted in being called an artist; his authorized biographer, Richard Evans, once wrote that McEnroe is a "pointillist tennis player," referring to the school of art fathered by Georges Seurat in which the painter uses only the tip of his brush.

Similarly, McEnroe, who was renowned for rarely practicing or watching what he ate, dominated stronger, bigger, more committed players with a wholly instinctive game that was characterized by a feathery touch, a series of jabs and wrist flicks that produced unfathomable, sharply angled shots. "McEnroe saw the court in different geometric dimensions than anyone else," says Eric Riley, a former tour player who has coached Pam Shriver, Lisa Raymond and the Jensen brothers. "On any given volley, the rest of us might choose between two or three shots. But somehow Mac would see all these possibilities that never occurred to anyone else before."

Yet, despite the seven Grand Slam tournament victories, the 77 singles titles (third all-time behind Connors and Ivan Lendl) and the No. 1 ranking from 1981 to 1984, it was the dark side of his artistry for which McEnroe became most widely known, the temperament that led him to be dubbed "McBrat" by the staid English press after he lambasted a stuffy Wimbledon umpire by screaming, "You are the pits of the world!"

It wasn't so much that McEnroe was supercompetitive; his rage for perfection in himself and others was just as likely to explode when he was winning. The tirades would invariably be followed by rambling public soliloquies of introspection ("Why do I let it happen?" he wondered once, after the Beast had run amok) showing both an innate intelligence and a stunning tendency toward self-flagellation. Behind the blowups was a self-loathing narcissism ("I'm so disgusting, you shouldn't watch. Everybody leave!" he screamed between points during the '81 Wimbledon tournament) and a class resentment in reaction to tennis' pretensions. He would rail against the sport's "phonies and elitists," earning him antihero status.

He hung with Jack Nicholson and Mick Jagger, both of whom offered similar advice after he'd been banned from the Davis Cup in 1985 and there were rumors of a yearlong suspension: Don't ever change. ("When you're 26, who are you gonna listen to, Jagger and Nicholson or some old farts in the United States Tennis Association?" McEnroe recalled in Sports Illustrated in 1996.) Nike signed him up (his total career earnings from tennis and endorsements are said to surpass $100 million, well beyond what any other tennis player ever made) and graced Sunset Boulevard with a James Dean-like mural of Johnny Mac on a city street, the collar of his leather jacket turned up. It was a fitting image, because long before Dennis Rodman or Latrell Sprewell, McEnroe was sports' preeminent rebel without a cause.

John Patrick McEnroe Jr. was born on Feb. 16, 1959, at the U.S. Air Base Hospital in Weisbaden, West Germany, where his father was stationed in the Air Force. When John was 9 months old, the family returned to Queens, N.Y., living first in Flushing before settling in Douglaston. John Sr. was Depression-era born and first-generation Irish-American, both of which may help explain his eldest son's later patriotism -- McEnroe is the all-time leader in Davis Cup wins -- and his class resentments. The senior McEnroe worked a day job while attending law school at night and eventually became a partner in the prestigious Park Avenue law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison.

John Jr. commuted to the tony Trinity School on Manhattan's Upper West Side. There, with its tweed-jacketed, pipe-smoking headmaster, McEnroe got his first taste of the stodgy upper class he'd later wage war against at Wimbledon. Yet he was well-behaved in high school, the odd subway turnstile jump while shouting "U.N. delegate!" notwithstanding. He was a stellar student who may have loved soccer more than tennis. But he fell under the tutelage of the legendary tennis coach Harry Hopman at the Port Washington Academy on Long Island and played junior tennis throughout high school. While his talent was clear, his dedication wasn't. He wasn't a top-ranked junior, and even garnered a reputation for giving close lines calls to his opponents.

In the summer of 1977, before heading west to play No. 1 singles for Stanford, McEnroe went to England to try to qualify for Wimbledon as an unseeded player. The pudgy, unknown 18-year-old stunned the sports world, making it all the way to the semifinals -- the first qualifier to ever do so -- before losing to Connors in straight sets. The next year, as a freshman, McEnroe was tennis' collegiate champion and was soon challenging Connors and Borg, who were dueling to be ranked the world's greatest player. Meantime, McEnroe's temper had exploded enough times -- and in close enough proximity to the court's microphones -- that he soon supplanted the roguish and sometimes crude Connors as public enemy No. 1.

Certain catchphrases became legendary, launched like verbal artillery at blank-faced umpires. There was, "You cannot be serious!" or "Answer the question! The question!" the last word emphasized with as much venom as words alone can contain. There was the time at the French Open when he screamed, "I hate this country!" and the time he told a tournament referee to "go fuck your mother." And there was the inevitable contrition afterward. "I know I've got a problem," he told his biographer Evans, author of 1990's "McEnroe: Taming the Talent." "When I walk out there on court, I become a maniac ... Something comes over me, man."

Yet the talent and the temperament seemed to work hand in hand. In exploding, McEnroe would create a drama with himself at its epicenter and, by raising the stakes, he'd more often than not raise the level of his play, as suggested by his first wife, the actress Tatum O'Neal. "All those negative responses, like 'I'm going to win because the crowd hates me, people hate me; I've got to beat the crowd, beat the officials,'" she lamented to Evans. "He makes life so difficult for himself."

But he won. In 1979, he won his first Grand Slam event, taking the U.S. Open. Then, in 1980, came the greatest match in the history of tennis, a five-set marathon loss to Borg in the Wimbledon final. The next year, McEnroe got revenge against Borg at Wimbledon and beat him again at the U.S. Open, toppling Borg from the world's No. 1 ranking and sending the mysterious, stoic Swede into early retirement at all of 26.

The rivalry with Borg, though brief, remains epic, because the two men were such a study in contrasts. Borg was the emotionless, patient baseliner; McEnroe, the loudmouthed, net-rushing New Yorker. Borg was the master of the passing shot; McEnroe, possessor of the quickest and softest hands at the net, the toughest to pass. When Borg left the scene, aficionados expected McEnroe to dominate, but McEnroe missed the rivalry too much and went into his own funk. It was Connors, instead, who won the 1982 Wimbledon and '82 and '83 U.S. Opens, but McEnroe wasn't done yet. Though he is best remembered for the wars with Borg, it is 1984 that should be McEnroe's lasting legacy.

In that year, McEnroe may have been the best player ever. He won 82 matches and lost just three, the highest winning percentage (.965) since the dawning of the Open era. His 6-1, 6-1, 6-2 dismantling of Connors in the Wimbledon final was arguably the most dominating display in modern tennis history: 78 percent of his slicing first serves in, most of them unreturned by the game's greatest returner, and perhaps the most astounding statistic in the sport's annals, only two unforced errors in the entire match. The angled volleys were sharper, the drop shots deadlier, the serve more meticulously placed than ever before. And this wasn't just anybody he was carving up on center court; this was Connors, one of sports' all-time competitors, who couldn't get back in the match. If all the tantrums and vitriol had come from the frustration born of perfection's elusiveness, then, for that one Sunday morning in England, there was finally no need to scream at anyone.

In keeping with McEnroe's nature to see every glass as half empty, he remembers 1984 not as the year of his greatest triumph, but of his greatest regret. Up two sets to none and five points from taking the match against Lendl in the French Open, McEnroe overheard voices on a television headset that was left unattended on the side of the court. Picking it up, he screamed "Shut up!" into it -- no doubt popping the eardrum of the poor unsuspecting technician at the other end -- thereby earning the enmity of the crowd. "I have this unique ability to turn the whole crowd around," McEnroe said afterward to Sport magazine. It was to be one of the few times McEnroe was unable to overcome the opposition of a hostile audience. Suffering from heat stroke, he lost in five sets.

After that year's U.S. Open, McEnroe would never win another Grand Slam or be ranked No. 1 again. It was as if the near-perfection of 1984 hadn't fulfilled him. More often than not, he seemed disgusted on the court. Brad Gilbert, now Andre Agassi's coach, describes an uproarious 1986 McEnroe meltdown in his book "Winning Ugly: Mental Warfare in Tennis." Gilbert was the mirror image of McEnroe, a player short on natural talent but long on workmanlike desire. "Gilbert, you don't deserve to be on the same court with me!" McEnroe snarled at his opponent during a changeover when it became apparent he might lose to him. "You are the worst! The fucking worst!" After the loss, McEnroe announced he was going on what turned out to be a seven-month sabbatical, because "when I start losing to players like him, I've got to start reconsidering what I'm doing even playing this game."

By then, the game of tennis was changing. Pure power players like Boris Becker, with his 125-mph serves, were ascendant, aided by new racket technology that increased power without sacrificing control. Though still one of the top two or three players in the world, McEnroe, with his artistic flair for finesse volleys and quirky angles, was suddenly a stylistic anomaly. In addition, for the first time in his life, tennis wasn't monopolizing all of his intensity. In 1984, McEnroe met his temperamental equal in O'Neal and the two wed in 1986 (the press dubbed them "Tantrum and McBrat") after he'd called her "the female John McEnroe." Indeed, she'd barred her father, the hot-tempered actor Ryan O'Neal, from the wedding when it was rumored that he'd called McEnroe "a jerk." After six years of marriage, five homes (including a Malibu beach house purchased from Johnny Carson for $1 million and three tennis lessons) and three children, O'Neal and McEnroe parted ways, ostensibly because she wanted to work and McEnroe wanted her home with the kids. "I've had a lot of experience with men who are bullies," O'Neal told Entertainment Weekly. "Taking on John McEnroe was the biggest struggle of my life."

In 1992, while his marriage was crumbling, McEnroe reached the semifinals of the U.S. Open and led the United States to a rousing Davis Cup win over Switzerland. While other top American players, ranging from Connors to Pete Sampras, haven't always made the Davis Cup a priority, McEnroe led the Americans to five world titles in 12 years. Fittingly, the last great moment of his tennis career came during the '92 Cup, when he played doubles with rising star Sampras. When the Americans won, McEnroe unfurled a giant American flag and ran laps around the court, waving it and screaming, the normally placid Sampras in lockstep.

Though he didn't officially retire, his tennis waned while McEnroe tried to find other outlets for his creative impulses. McEnroe had visited his first art museum in 1977, when his mixed-doubles partner and childhood friend, Mary Carillo, took him to a Claude Monet exhibit in Paris during the French Open. "I remember him standing in front of one of the great Monets and saying, 'You gotta be kidding, my brother Patrick has better stuff than this on the front of our refrigerator!'" Carillo told the Guardian in 1994. "But I guess he's coming around. He always did like to hang around eccentric, creative people."

Later, the late Vitas Gerulaitis, a fellow pro and New Yorker, started ushering him around SoHo galleries. He bought his first painting, by the realist Audrey Flack, at a gallery on Prince Street and began visiting museums and galleries nationwide while on the tennis circuit. In 1993, while separated from O'Neal, he apprenticed at a gallery on East 79th Street, spending all day looking at art. "I was really down and out at the time," McEnroe told the Independent in 1994. "I had just been separated and it was a godsend to be able to go to a place every day and keep my mind off what was going on. Because of that, I became more interested in the idea of doing something on my own."

He opened the John McEnroe Gallery in SoHo the following year. "There are a couple of connections between art and tennis," McEnroe told the Independent. "People in the art business have a tendency to one day tell you you're the greatest artist that ever lived and the next second make you wonder if you'll ever sell a piece of art again. So I think I have a knowledge of that, because you have a fear when you go on the court: fear of failure ... I understand [artists] are needy and insecure."

In recent years, McEnroe's passion for the business side of art has lessened. First, he shifted his focus to rock music; years ago, friends such as Eric Clapton had tutored him in guitar. He formed a band and began working on an album, but inexplicably quit a couple of years ago. "I think it was a combination of fear of success and fear of failure," the band's manager told the New York Times Magazine earlier this year. His foray into rock 'n' roll did introduce him to his current wife, Patty Smyth, who sang "The Warrior," a top hit in 1984. Together, they have two children of their own, to go with McEnroe's three from his union with O'Neal and Smyth's daughter from her previous marriage. Four years ago, the National Father's Day Committee, a New York nonprofit organization, named McEnroe father of the year. When he's not traveling these days, McEnroe can be found every morning walking his 9-year-old daughter Emily to school. "By having kids, I got my humanity back," he told Sports Illustrated in 1996. "I'd been like some tennis dude, No. 1 in the world and not happy with it."

Most recently, McEnroe has become re-energized about tennis, having been appointed Davis Cup captain, a position for which he's long lobbied. His first act was to convince the top two names in the men's game, Agassi and Sampras, that Davis Cup ought to mean something to them. When the U.S. team beat Zimbabwe in February, there was McEnroe stalking the sidelines, earning a warning for bad language and accusing the judges of holding old grudges against him. And he has been dominating the senior tennis circuit, even if the old demons still surface on court.

His TV commentary during Wimbledon and the U.S. and French Opens has won plaudits for him as the best sports announcer this side of football's John Madden. He's outspoken, smart and funny. But even in the booth he is never too far from controversy. A few years back, he took some shots at his longtime friend Carillo, suggesting that women should not commentate on men's tennis. But he didn't stop there. "I don't know any women who know the men's game," he said at a press conference. "At the same time, I'm not sure men can really know the women's game. I mean, how would they know how women are feeling at a certain time of the month?"

It was further proof of the many contradictions within McEnroe; though he'd long been one of tennis' few progressive thinkers on race -- he refused to play a $1 million exhibition in Sun City in the mid-'80s due to his opposition to apartheid -- he'd often seemed like a Neanderthal when it came to women. For her part, Carillo expressed hurt and disappointment in her friend. "So much of his graceless and disappointing behavior comes from not looking beyond his own feelings," she told the Guardian. "Like many great artists, he has a self-destructive side."

In his biography of McEnroe, Evans reports that the actor Tom Hulce studied the behavior patterns of McEnroe while preparing for his role as Mozart in "Amadeus," as did the great Shakespearean actor Ian McKellen for "Coriolanus." Evans quotes a description of Coriolanus from author Peter Levi's "The Life and Times of William Shakespeare," and, indeed, it could just as easily apply to the tennis great:

The origin of all lay in his unsociable, supercilious and self-willed disposition, which in all cases is offensive to most people; and when combined with a passion for distinction passes into absolute savageness and mercilessness ... Such are the faulty parts of his character, which in all other respects is a noble one.

For more than 20 years on the public stage, John McEnroe has been unafraid, or unable, to keep suppressed the darkness most of us don't even admit to ourselves. It would be nice to believe that, as he is wont to suggest, McEnroe has, in his 40s, taken solace in his family and found peace.

But there is also no denying him a sense of grudging admiration, for it takes something -- a death wish? a kind of courage? -- to so flagrantly parade the inner Beast, as he did June 16 on that Central Park tennis court, while Smyth and 5-year-old daughter Anna looked on. And there he was in the press conference afterward, moaning about how fans at other events across the globe always cheer louder for him than they do in his hometown, conveniently glossing over the fact that, as always, he'd had the crowd -- and promptly lost them by loudly proclaiming some among them to be assholes. "I don't know, maybe it's my fault, I don't know," he mumbled in a monotone. Despite the flatness of tone, you could sense that, somewhere, all the old emotions were in play. Somewhere in there, John McEnroe was beating the hell out of himself.

Shares