"The thing about ... Michael Caine is ... that he only ... speaks t'ree words ... at a time." That was British actor Jim Dale mimicking Caine's distinctive stop-and-start cockney inflections. It's a compliment, really, an acknowledgment that Caine had joined the select body of movie stars whose speech and mannerisms are so familiar they can be parodied. It must have tickled the former Maurice Joseph Mickelwhite, who took his name from a marquee advertising "The Caine Mutiny," starring one of his all-time favorite actors, Humphrey Bogart, to have gained entrance to such a select club. (Just as it thrilled him, in John Huston's "The Man Who Would Be King," to be playing a role originally intended for Bogart.)

Michael Caine, who had an easy birth on March 14, 1933 ("the last easy thing I was to do for 30 years," he has said), seems as familiar as any actor to have emerged in the past 40 years. We all think we know him. The ska group Madness named a song after him and punctuated it with the actor's voice announcing simply, "I am Michael Caine." In the midst of Eddie Izzard's one-man show "Definite Article," the English comic suddenly veers into dialogue from Caine's 1969 caper flick, "The Italian Job," and the English audience erupts in laughter of recognition with each new line. Roy Budd's score for Caine's 1970 tough-as-nails "Get Carter" (recently voted by British critics as the greatest British gangster film of all time) has been flying out of specialty CD shops on a pricey British import that features bits of Caine's dialogue between the music tracks. (A remake starring Sylvester Stallone and featuring Caine in a supporting role is due out Friday.)

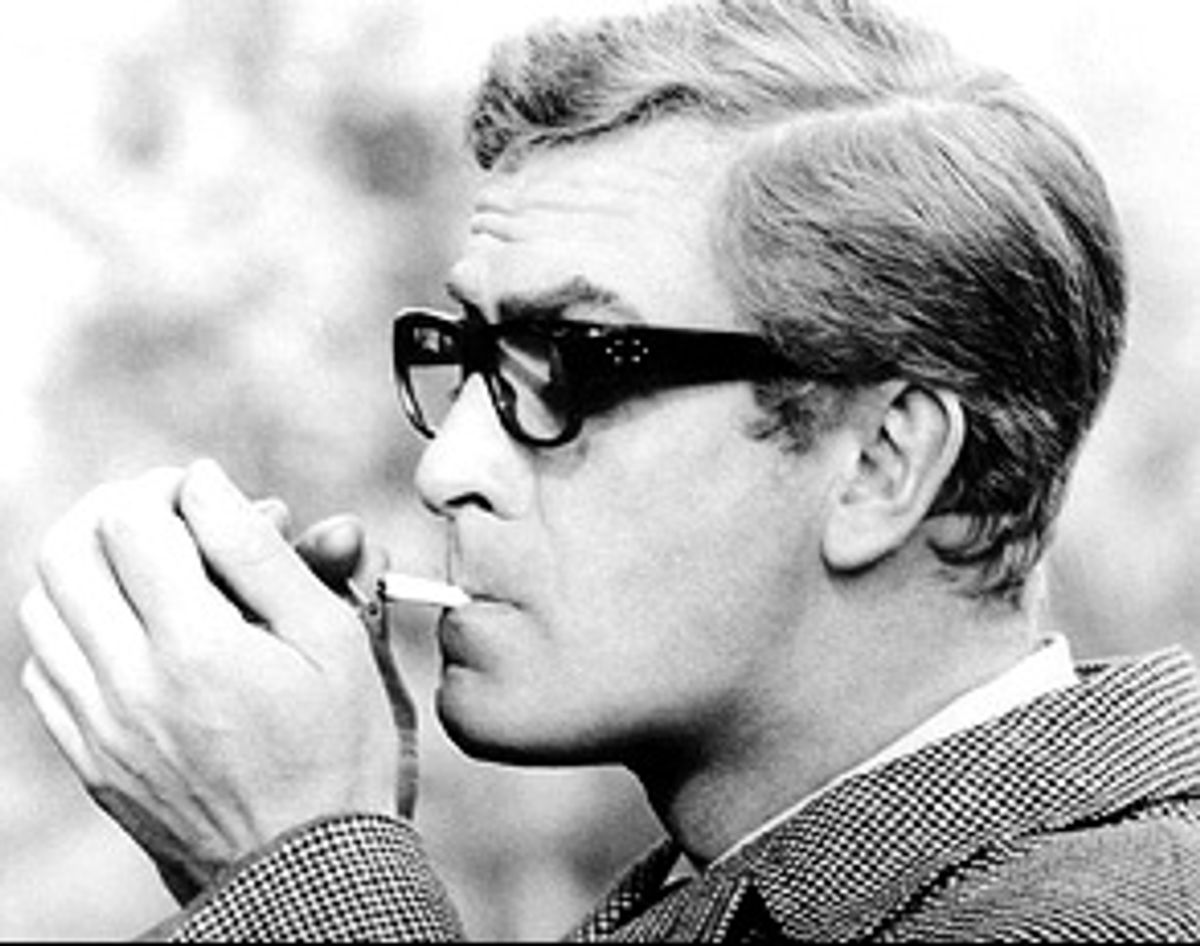

The iconic image of Michael Caine is probably best summed up by a 1965 David Bailey photograph recently reprinted in his book "Birth of the Cool." In it, Caine wears the black horn-rimmed glasses he donned to play secret agent Harry Palmer in three films that began with "The Ipcress File." An unlit Gauloise dangles from his mouth, and his black suit, tie and white button-down shirt are slim and immaculate. But there's something unstable about the photograph, an unnerving aliveness that, 35 years later, still makes its meaning impossible to pin down, cut loose from its era as much as Bailey's chic portraits of other icons of '60s Brit cool -- Jean Shrimpton, Mick Jagger, even the Kray Brothers -- are contained by their times. The portrait is bordered by the edges of the black frame, but Caine's eyes make you feel as if you're the one who has been nailed to the wall. Steady, cool to the point of frigidity, they look as if they're glowing from within their partially shadowed sockets; the long eyelashes that frame them might be tiny laser beams. Caine's impassive expression and ray-gun orbs don't offer the certainty of either kindness or cruelty but something far more unsettling: the sensation of being coolly appraised, of having each action or utterance totted up and held to your credit or debit.

Looking at that picture now, I can't help feeling that it holds the key to the range and contradictions of Michael Caine -- not just the key to how a great movie star became a great actor but the key to how such an essentially warm actor (and one moviegoers think of warmly) has been able to play cold. In "What's It All About?" his enormously entertaining autobiography, Caine rather startlingly reveals that something other than his love for Bogart led him to take his name from a movie marquee. "Cain was the brother of Abel," he writes, "who was cast out of Paradise, and I felt a great sympathy with him at the time." Caine means that as someone scraping professional bottom after a promising start, he knew what it felt like to be suddenly on your uppers.

But could that understanding be part of what has made him so memorable when he has played bastards? The young Maurice Mickelwhite dreamed of being a movie star. Yet Caine has escaped the perennial curse of movie stars: vanity. He has never shied away from a role because he was afraid of losing the audience's sympathy. That has been true from the beginning, when he gained his first huge success as unrepentant cad "Alfie," through to the preoperative transsexual killer in "Dressed to Kill," slimy underworld king Mortwell in "Mona Lisa," the put-out-to-pasture middle-aged businessman who resorts to murder in "A Shock to the System" and the sadistic, Torquemada-like psychiatrist in the upcoming "Quills."

There are certain actors (Christopher Walken, for instance, or Harvey Keitel) whom we expect to play villains. And after a while, they are robbed of the power to unsettle us. Go see Walken or Keitel now, even at their best, and you're more likely to chuckle in pleasure at the way their villainy fulfills our expectations. Caine's villains are so effective because, in his other roles as well as in his public persona, he seems the most levelheaded of actors.

The tone that pervades "What's It All About?" is one of someone who has gotten used to luxury but doesn't take it for granted. The former Archibald Leach may have said, "Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant." But part of Caine still seems to be Mickelwhite. He is refreshingly free of guilt about being an actor who has worked for financial security. ("I have never seen ["Jaws: The Revenge"] but by all accounts it is terrible. However I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific.") There's a famous story about his being treated as a cockney scruff by a Rolls Royce salesman, who saw Caine just a few hours later when the actor rode past the fellow's showroom in a Rolls he'd purchased from another dealer, giving a two-fingered salute. In an interview a few years ago, he told one of those stories that make you laugh even as your eyes are tearing up. When money was no longer a concern for Caine, he told his mother that he could now take care of her and asked what she had always wanted. "Would it be all right," Caine's mum responded, "if I were to order an extra quart of milk, because sometimes I run out by the end of the week?"

Caine possesses a smoothness, a star quality that transcends class, a believability that has made him convincing as everything from an international movie star ("Sweet Liberty") to a variety of lowlifes and losers ("Mona Lisa," "Little Voice") to a swank Riviera con man ("Dirty Rotten Scoundrels") to Manhattan businessmen ("Hannah and Her Sisters," "A Shock to the System") to an Oxford professor ("Educating Rita") to a small-town doctor ("The Cider House Rules"). But in the '60s, when his career took off, Caine was the movies' quintessential cockney.

You can talk all you want about the changes wrought on British culture by John Osborne and the Angry Young Man school of writing, or by the theatrical experiments of director Joan Littlewood (who told Caine, after his short stint in her company, "Piss off to Shaftesbury Avenue; you'll only ever be a star"), or by the writing of Allan Silitoe and Shelagh Delaney. Those artists reached primarily intellectual, educated audiences. It was the Beatles who, reaching everybody, sent the British class system topsy-turvy. Suddenly, people were affecting Liverpudlian and cockney accents instead of upper-crusty ones. Suddenly, being born in the East End was more desirable than being listed in "Burke's Peerage." The aristocracy was a closed club; the joys of the new "ruling class" were open to anyone who responded to the excitement that carried the day.

Caine's entry into acting had nothing to do with the British tradition of theatrical training. He started acting as a teenager in youth clubs, and after his National Service, moved on to stage managing and small roles at a little theater company, and from there into regional repertory, TV and small movie roles. By the time he became known in the '60s he had already been acting for some years. (He had also gone through his first marriage and had a daughter, Dominique.)

Despite his role as official cockney, producers almost didn't see it that way. Caine lost a part as a cockney in "Zulu," only to be cast in his first big movie role as aristocratic snob Lieutenant Bromhead. Speaking in an upper-class accent that contained a wafer's edge of parody, Caine modeled himself physically on Prince Philip, clasping his hands behind his back in the manner of "a powerful man and well guarded so he did not have to be ready to defend himself as the unguarded lower orders do. He never had to open doors or do other mundane things for himself." The response from a senior Paramount executive in London who saw the rushes was a telegram that read: "ACTOR PLAYING BROMHEAD SO BAD HE DOESN'T EVEN KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH HANDS ... SUGGEST YOU REPLACE HIM." Luckily, director Cy Endfield knew when to ignore studio executives. The movie was a big hit, and Caine got great reviews but not the contract he had hoped for. Famous producer Joseph Levine, president of Embassy Pictures (which made "Zulu"), told Caine the studio was not picking up his option because "you look like a queer on-screen." (This, incidentally, was 1964, the same year Rock Hudson was ending his seven-year run as the top box-office attraction.) But Caine's performance attracted the attention of producer Harry Saltzman, who cast him as spy Harry Palmer in the film of Len Deighton's bestseller, "The Ipcress File."

The movie marks the beginning of Caine the icon. Right down to his ordinary-bloke name, Harry Palmer was conceived as the antithesis of James Bond, the spy as civil servant (though not one of the tortured and rumpled denizens of John le Carri's gray world). The result is a movie that's static and unsatisfying, a pop entertainment without the kick of pop (which was the distinctive joy of the Bond films). But Caine's Palmer, competent, disrespectful to his superiors without being flagrantly insubordinate, was a coolly contained version of the working-class cheek that had won over British culture. Palmer's targets can never quite tell whether he's sincere or taking the piss.

It was his next role, as Cockney cad "Alfie" (a role that Caine had tried for and lost in the stage version), that would not only make him a star but give a hint of the fearlessness that would make him a rarity among movie stars. The part had already been turned down by other British actors, who knew that playing a bastard who uses women guiltlessly wouldn't win them audiences' sympathy. When Alfie Elkins loses interest in a bird, he knows she can still be handy to keep around for laundry and meals, and no matter how badly he treats women, to Alfie, it's never his fault. Caine's inspiration was to say the hell with sympathy. Narrating much of the story directly to the camera in a thick cockney accent, Alfie puts all of his charm at the purpose of his self-justification, trying to make all of us in the audience his marks. It's not a great movie. The director, Lewis Gilbert, can't resist the material's "sensitive" touches, like Alfie's guilt over his son being raised by another man. But he never shortchanges the hurt of the women, particularly Vivien Merchant, who's quietly spectacular as the plain housewife for whom Alfie has to arrange an abortion. The triumph of the movie is contained in that sequence, in Gilbert's dead-on handling of the seedy atmosphere, and in Caine's awareness of Alfie's blissful ignorance that this coldhearted stud is only a few years away from going to seed himself.

The key to Caine's performance as Alfie, in a way the key to all his acting, is the lightness of his approach. In his autobiography Caine tells a story about Jack Lemmon making his movie debut for George Cukor, who, after every take, kept telling the actor, "Do less." Finally, Lemmon said, "If I do any less, I'll be doing nothing," to which Cukor replied, "Now, you're getting it." Caine has learned that subtlety as only a handful of great film actors ever have.

There's another kind of subtlety at work in the 1986 British thriller "The Whistle Blower," one of the spate of movies made in disgusted reaction to the contempt for simple human decency that characterized every aspect of Margaret Thatcher's rule. Caine plays a former army man whose son (Nigel Havers), a Russian translator for British intelligence, is murdered when he stumbles onto the government's scapegoating of an innocent man. Caine's performance in "The Whistle Blower" is one of his very best. Loath to believe that his England engages in the dirty dealings other countries do, Caine's character must come to terms with the fact that his son's death negates everything he has ever thought was true. His finest moment comes shortly after he has to identify his son's body; a functionary brings in his son's belongings in a green garbage bag, and after signing for them, Caine holds up the bag and asks, "I suppose this is cheaper than a cardboard box or something decent?" That's one of the hardest things for any actor to do: to impart a sense of shame to another adult without a trace of self-righteousness. In that one line, Caine lays out something like an ethics of functioning as a human being, an awareness that every moment involves a choice of whether or not to behave humanely.

Through his whole body of work, Caine has raised his voice sparingly, almost always saving overt shows of anger for comic effect. Like the scene in "The Italian Job" where he's sorting out the petty complaints of his crew of thieves before they pull their big job ("Yer not havin' yer me-graine! Yer not bein' sick! An' yer both sittin' in the back of the mini!!"), or the scene in "The Man Who Would Be King" (featuring, in a small part, his wife, Shakira, whom he married after falling in love with her face in a coffee commercial) where a Kaffir he's trying to train in British military discipline can't even count off in time with his fellow recruits ("Billy! Billy! He said it before the others! Not before the others! Not after the others! With the bloody others!!").

The exception is his final scene as small-time theatrical agent Ray Say in "Little Voice." In his early scenes with the astonishing Jane Horrocks as the painfully shy girl whose uncanny vocal imitations he hopes will make him the fortune he has sought for so long, Caine is sweetly seductive, solicitous of the girl. She's his gold mine, but he cares for her as well. "Little Voice" is one of those unfortunate movies in which characters are finally no more than the sum of their worst impulses, but Caine explodes the cheap misanthropy. His hopes dashed, his pockets bare, he mounts the stage in the sort of crummy nightclub where, for years, he has wheedled and cajoled the slimy owners to book his pathetic acts. Letting out all the contempt he has held in for decades, Caine launches into a lacerating, self-pitying version of Roy Orbison's "It's Over." He's like a mad bomber using the song as dynamite strapped to his chest, determined to detonate it and drag everyone around down with him.

That lightness that does not exclude depth is precisely why Caine is so menacing in his villain roles. He's the hero in "Get Carter," Mike Hodges' macho pulp thriller, which has achieved mythic status in Britain. But Caine plays British gangster Carter, returned to his hometown in the bleak industrial north to find the men who murdered his brother, as if he were a villain. He tosses off the most cutting remarks (and dispatches his enemies) with ice-cold aplomb. In a scene in which he runs into an old despised acquaintance and presses him for information, Caine doesn't allow Carter's contempt to come out until the end of the scene, and he does it so frigidly you feel years sliding off the other guy's life. Lifting the man's sunglasses off, he says, "Do you know, I'd almost forgotten what your eyes looked like. They're still the same. Piss holes in the snow."

Caine appears only intermittently in Neil Jordan's "Mona Lisa," but those appearances are vivid enough to turn the film's pulp-romantic dream into a nightmare. As Mortwell, the underworld king whose fingers are in every sordid pie that presents itself to him, Caine more than lives up to the character's name. Oozing Vitalis more than vitality, looking puffy and sated in his too-tight polo shirts and Members Only jackets, Caine is a walking portrait of death in life. His droopy eyelids belong to someone who willed his conscience and emotions dead a long time ago. For all the paunch that's a sign of Mortwell's success, he might as well be a death's head, his quiet threatening air a looming reminder to all who encounter him of their final destination.

There's a mischievousness to the villainy Caine undertakes in Philip Kaufman's brilliant and unnerving Gothic drama "Quills," which opens in November. As unscrupulous psychiatrist Dr. Royer-Collard, charged by the French king with breaking Charenton asylum's most famous resident, the Marquis de Sade (superbly played by Geoffrey Rush), Caine wears the mask of civic virtue that hides festering rot. The movie spirals into horrors that even Royer-Collard can't contain. And as it does, you see something like stone enter his countenance, a mounting determination to clamp down even tighter on the deviance that so offends his propriety. This is one of the performances where Caine uses his winning open smile as a mark of deviousness. Playing a louse of a man who pretends to the highest public demeanor, he is the Kenneth Starr of the Terror. His smile is a slap in the face, a promise across the centuries that the deeds of bastards carried out in the name of decency are far from done.

In the four decades he has been starring in movies, Caine has managed to go from generating amazement that he held his own next to Laurence Olivier in 1972's "Sleuth" (a backhanded compliment -- the material is worthy of neither of them) to recognition as a master actor. Because Caine has literally dozens of films to his credit, some of the best have slipped through the cracks. I urge you to check out "The Whistle Blower"; Jan Egleson's crafty, malicious thriller "A Shock to the System"; and the tense, workmanlike political thriller "The Wilby Conspiracy," in which Caine plays an English businessman who, during a vacation in South Africa, gets involved with saving the life of an escaped political prisoner, played by Sidney Poitier. This past spring, hours before he won his second Oscar for "The Cider House Rules" (he won his first for a skillful but not terribly flattering performance in "Hannah and Her Sisters": There's not much pleasure in watching Woody Allen foisting his neuroses on as grounded an actor as Caine), he was asked what two movies of his entire career he would keep. He answered "Cider House" and "Educating Rita." Good choices.

Caine may never have gone deeper than he does in "Educating Rita," which was directed by "Alfie's" Lewis Gilbert from Willy Russell's play. As Frank, a perpetually sozzled Oxford prof and stymied poet, Caine delivers perhaps the gentlest portrait of self-loathing ever in the movies. Frank is disgusted with himself for not producing any more poetry, disgusted with the poems he did produce, disgusted with the way he goes through the motions for students who regard him as an academic freak show, a souse who's better for a laugh than a seminar. Frank may be faking, but he's no fraud. The soul hasn't burned out of the man, just gone into weary retreat. "Educating Rita" is about how he finds his way back with the help of a working-class hairdresser (Julie Walters) he tutors in an adult-ed program.

You can see Frank's anguish in Caine's watery eyes, his bloated gut and the curly hair and beard he seems to be doing his best to hide behind. He looks like a boozy, overgrown rabbit, and there's something soft, almost caressing, about Caine's performance. Without diminishing any of Frank's waste or weariness, Caine portrays the dilemma of an unmoored man heading for oblivion as delicately as a solitary balloon mounting mournfully skyward. And he tries to deflect Frank's caught-in-the-headlights terror at not knowing where to jump next by masquerading as a man calmly contemplating his next move. We register the calm, but we feel the panic underneath. It's a portrait of lost (and reclaimed) human potential that bestows the greatest gift the movies can: a heightened, expansive sense of what it means to be human.

As Dr. Wilbur Larch in "The Cider House Rules," Caine might be taking everything he has learned about acting and distilling it down to its essence. The whole performance is one of an actor defying the minefields of sentimentality to achieve purified and thorny emotion. Caine manages the tricky feat of making sternness equal love without going soft or becoming a lovable old codger. The exasperation he directs toward his protigi, Homer Wells (wonderful Tobey Maguire), manages to make Larch's heartbreak at the prospect of losing Homer clear without ever becoming explicit. Caine's utterly straightforward performance is an exquisite piece of transparent misdirection, a portrait of a man who makes his feelings obvious by what he doesn't say.

Any actor, if he or she is good enough, begins, over the course of a career, to suggest links between the actor's characters, not just by familiar inflections or gestures but in the way some characters seem to be living out alternate versions of other characters' lives, confronting the same demons, winning or losing, or at least figuring out how to keep body and soul together. Wilbur Larch has won the battle that the disillusioned patriot Caine played in "The Whistle Blower" may wind up losing. He has accepted life as it is and not as it should ideally be. Larch's central speech, his justification for performing abortions, is an argument for the possibility of decency and honor amid ugly choices. Ministering to a 12-year-old girl who has attempted to abort her fetus with a crochet hook, Larch says to Homer, "This is what doing nothing gets you ... It means that someone else is going to do the job -- some moron who doesn't know how!" Caine delivers those lines with the sort of unimpeachable authority that only a few actors are ever lucky enough to achieve. Larch is a small-time, small-town country doctor, and his escapes into ether dreams notwithstanding, he has the immense stature, the cant-free moral authority of the movie characters who embody heroic decency.

Caine has said that he now looks at the quality of a part rather than its size. But he has reached the place where the roles that come his way are going to have to measure up to him. Caine slips effortlessly into Larch's sensible, battered brown shoes and finds, after 36 years of movie stardom, that they are a perfect fit. Though Prime Minister Tony Blair recently made him Sir Michael Caine, his aristocracy seems to derive from another source: He's the type of actor who is elevated to the status of movie aristocrat by the sheer love of his audience. He is that irresistible combination of an actor who feels both close to us and larger than us. Maurice Joseph Mickelwhite is no longer the man who would be a movie king. He's the only kind of aristocrat whom people take to their hearts. One of ours.

Shares