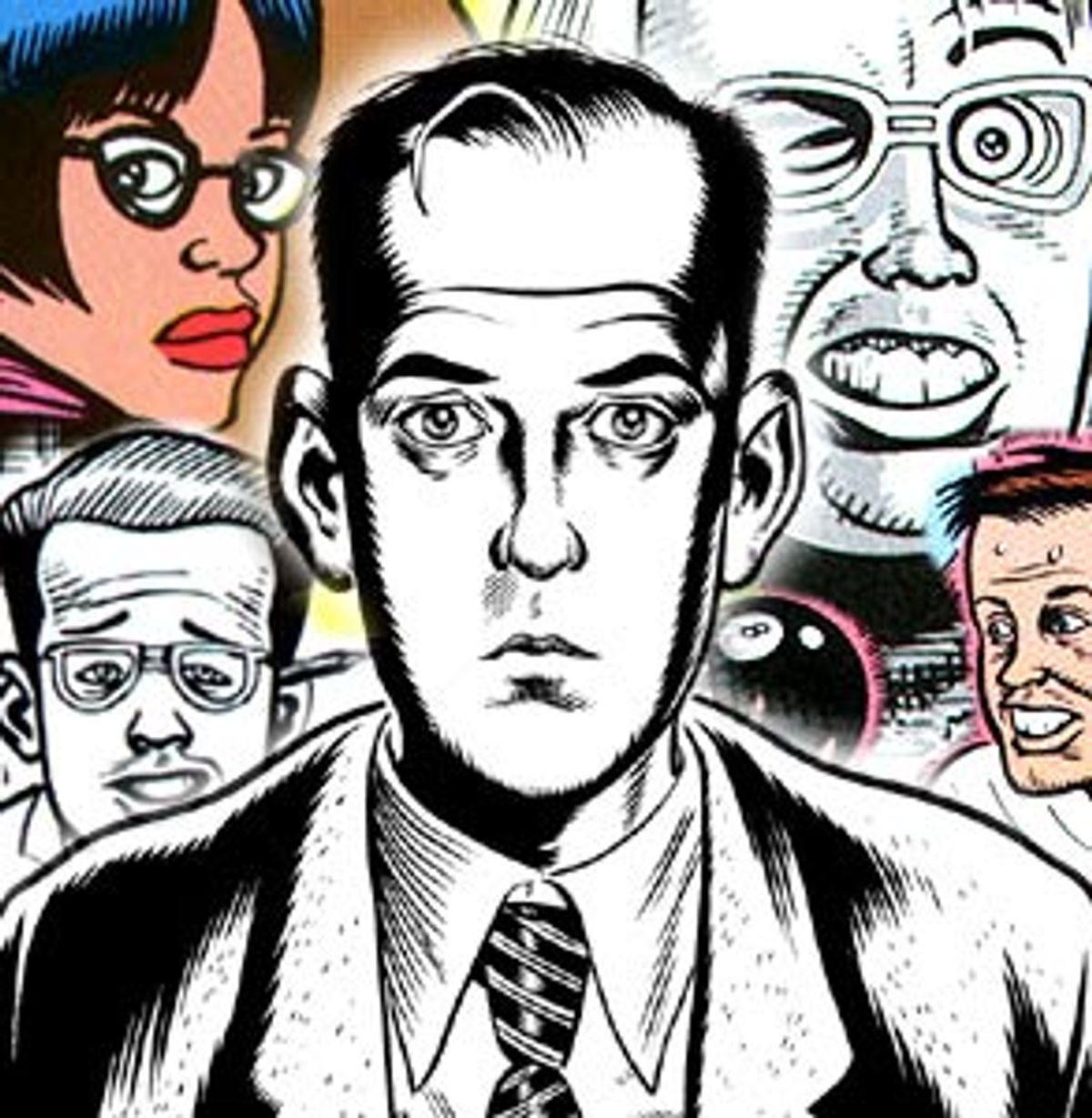

Daniel Clowes opens the door to his Berkeley, Calif., house, and the image of him standing there -- as if in wary anticipation of some unforeseen but likely horror -- recalls at least half a dozen of his comic book characters in action. Clowes himself is ethereal in a way that makes you wonder if his feet are actually touching the ground. He resembles one of his creations, with their neatly pressed, buttoned-down clothes and tentative, slightly anxious eyebrows hovering in mid-forehead. Framed by the straight lines of the doorway, it's almost as if he has drawn himself -- just before finding Tina, the potato-headed mutant from his first serialized story, "Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron," naked and sobbing on the steps.

Clowes -- whom fellow cartoonist Chris Ware calls "easily the best cartoonist in America" -- is probably most famous for his original comic book series "Eightball." "Eightball" has been variously described as a "cult," an "alternative" and an "underground" comic -- meaning that Clowes doesn't draw mutants, aliens or men in tights. Or rather, when he does, his mutants are lonely teenagers working as waitresses at roadside diners, his aliens -- sports fans, New Agers, stockbrokers, idealists -- are terrifyingly terrestrial and his spandex-clad crime fighters pop up primarily in the ardent fantasies of Young Dan Pussey (pronounced, of course, "Poo-say"), superhero comic book "penciller" and recurring "Eightball" underdog turned insufferable success.

Success spoiled Dan Pussey, but it definitely hasn't spoiled Dan Clowes. If Clowes is a cynic, then a cynic is a disappointed romantic who takes the world very, very personally. Twice a year for the past 11, "Eightball" has mercilessly taken on middle-class conformity, artistic pretension, teen angst, cartoonists, hipsters, the horrors of adulthood, proselytizing Christians, sports fans, sexual banality and desperation, advertising, consumerism, the entertainment industry and, perhaps most consistently, Clowes himself -- in haunting, hilarious and beautifully rendered stories of every length. While his drawings are darkly beautiful and eerily precise, typically the characters of "Eightball" fall somewhere between plain and repulsive. "My mom would always say, 'Why are your people so ugly?'" laughs Clowes, whose take on his characters has softened somewhat over the years. The sharp, scathingly misanthropic energy of the early-'90s "Eightball" has mellowed into a moodier, more melancholy empathy without losing any of its satirical bite.

"Somehow," says colleague Ware (whose graphic novel "Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth" was recently published), "he's able to blend satire and sympathy, two sensibilities which are generally mutually exclusive."

Now on issue No. 21, "Eightball" is one of Fantagraphics' bestselling titles (along with Ware's astonishing, hyperelaborate "Acme"). In his 15 years as a professional cartoonist, Clowes has won numerous Harvey Awards (including ones for best writer, best continuing series and best single issue); published seven graphic novels, among them the recent "David Boring"; and written the screenplay for the upcoming Terry Zwigoff-directed feature film "Ghost World" -- which is being produced by John Malkovich and will star Thora Birch and Steve Buscemi -- from a story first serialized in "Eightball" and later published as a graphic novel of the same name.

Clowes' house is calm, quiet and crammed with meticulously arranged and organized stuff that makes you want to sit on the floor immediately and start rummaging through it. His office, in particular, is an art director's dream. Books line the wall-to-wall shelves, and freshly drawn panels rest on a wooden drafting table, patiently awaiting ink. Clowes and his wife, Erika, whom he met on a small-scale California signing tour in 1992 ("I had just gone through a depressing separation from my first wife, and was trying to escape from the grim horribleness of Chicago; a beautiful young woman in Berkeley asked me to sign her underwear, and the rest is history"), will soon vacate the house for a larger one not far away. When I remark on the enviable order of the place, Clowes tells me it is neater than usual because he's expecting movers, who will be arriving soon to give him an estimate.

"Actually, they're packers," he amends. "Did you know that those are separate jobs? I didn't know until a good friend of mine turned out to be a packer."

Packer or mover, it's hard to imagine either would require a customer's folders to be labeled in artful, award-winning lettering and arranged by date. Then again, the kind of movers Clowes would create just might. And then they might tie him up, carve a supermarket logo into his heel and make rare Asiatic sea crustaceans come out of their eyes. When I point this out, Clowes admits to his penchant for structure. "I whipped my wife into shape," he says. "She got tired of having me ask, 'Why is this not in alphabetical order?'"

"Ghost World," which gradually took over the pages of "Eightball" before "David Boring" almost entirely engulfed it, was a marked departure from the nightmarish underworld of Clowes' first serial, "Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron." For one thing, the protagonist of "Ghost World" is a teenage girl; for another, the sense of horror that pervades "Ghost World" did not depend on strange, supernatural happenings or secret parallel worlds.

There has always been a feeling of jittery unease underscoring Clowes' work, but in "Ghost World," the sense of dread and horror emanates more from the real world than from the supernatural one. The creepy disquiet of "Ghost World" is nourished by television, suburbia and the soul-sucking banality of both. The serial's panels are cast in the eerie blue light of the television -- which is always on, always talking, never saying anything.

"Ghost World" is the melancholy story of the tail end of a friendship between two alienated teenage girls, Enid Coleslaw (her name is an anagram of "Daniel Clowes") and Becky Doppelmeyer, who live in a strip-mall-studded, palm-tree-lined, undifferentiated world of fake '50s diners and existential pain. Whatever hurt they don't experience themselves, they cruelly inflict on others. Enid, in particular, does not suffer America quietly. She mercilessly baits and humiliates the disenfranchised and disappointed adults she sees all around her while narrowing her world of acceptable people to two.

Clowes doesn't even exempt himself from the ranks of creepy adults who seem to exist only to let down Enid and Becky. In one episode, when Becky accuses Enid of being a man hater, Enid defends herself by claiming that her ideal relationship would be with the "famous cartoonist David Clowes." Yet when she shows up at a comic book store where he's scheduled to make an appearance, she finds a vaguely creepy guy sitting alone at a table in the back of the room, hiding behind a stack of comics.

"I felt I had given myself a privileged position to eavesdrop on her world, and it was only fair that she should hold me to the same scrutiny that she does everyone else," says Clowes on why he chose to make himself repulsive to his favorite character. Disappointed, Enid takes off without meeting him.

Clowes' knack for capturing this particular brand of arty teen-girl angst was so uncanny that he has since been accused of following young girls around and spying on them with a tape recorder. But like most of his characters -- some of whom make no bones about being just "another transparent D. Clowes stand-in" -- Enid is a fully realized character whose struggle to define herself and understand the seemingly unreal world around her reflects her creator's main preoccupations. As Enid embarks on the painful quest to become her adult self, she leaves the more passive Becky behind.

"When I started out I thought of her as this id creature -- totally outgoing, follows her impulses. Then I realized halfway through that she was just more vocal than I was, but she has the same kind of confusion, self-doubts and identity issues that I still have -- even though she's 18 and I'm 39!"

In "Ghost World," Clowes captures the way real teenagers simultaneously devour and reject the bogus images of themselves produced by the media. In the first episode, Enid chastises Becky for reading Sassy magazine, which is staffed by "trendy, stuck-up, prep-school bitches who think they're 'cutting edge' because they know who Sonic Youth is." At the end of the episode, Enid is kicking back on her bed, flipping through the magazine's glossy pages and muttering, "God, look at these stupid cunts." ("She loves it," says Clowes of Enid's closet Sassy obsession. "She can't stop reading, but she hates it.")

Clowes had problems with Sassy too. The magazine once swiped a frame from "Eightball," used it as an illustration and never paid him for it, despite his polite requests. So by the time he began work on "Ghost World," he was a man with a mission: "I want to create two girls who are much cooler than anything in Sassy, and who will make people not like Sassy." Ironically, Clowes' own experiences in Hollywood dispelled any notions he may have had about the movie industry being any more clued in to the way teenage girls think than the magazine world is. Even Clowes, a professional cynic, was taken aback by the sheer weight of the institutional mediocrity and lack of insight that daily threaten to crush any and all fresh ideas that manage to crawl into its sight.

"The things that happened were all the things you would think of. You think the fiction of Hollywood has to be exaggerated, and it's just not. I was shocked. I always thought there were really smart people working in Hollywood who were just really cynical, and they knew that the movies they were making were not that good, and they were doing it because they tested well. But mostly it's a very middlebrow to lowbrow kind of town. And they're making films that they approve of.

"It's also a very parochial world. If you have any sort of outsider's vision at all -- and I consider 'Ghost World' to be just a hair outside something that anybody could understand; this is not exactly a Samuel Beckett play -- they treat it like you are turning in 'Gummo' or 'Last Year at Marienbad.' They treated 'Ghost World' like it was this outrageous art film that nobody would get. And it's just a coming-of-age story that's only slightly different than what they're used to. They would say, 'Oh, it's great, we'll get Jennifer Love Hewitt.' And we'd think, 'Wait, that's what this is opposed to!' I'm sure she's a nice person and everything, but she's got the opposite personality than these girls have! And they would say, 'Oh. I thought she was supposed to be really pretty.'"

Clowes and director Zwigoff met with a lot of resistance, mostly from men, who argued that Enid and Becky were not representative of real teenage girls. "They'd say, 'Girls don't talk like this. Girls don't swear.' It's like this weird patriarchal thing that goes down the line. The guys in charge are very concerned with that. They really refused to believe that these were realistic characters. And then, of course, all the 20-year-old women there were like, 'No, these are realistic characters.'"

It took Clowes and Zwigoff years to get enough money to make "Ghost World" right. Raising the money and finding someone to finance their vision were "an ordeal, such a chore." There were years of sitting by the phone every day, of big meetings at which someone would say, "I love it! You have to change this and this and this." "Ghost World" was paraded by every studio in town before an acceptable deal was made.

On the bright side was working with Zwigoff, which Clowes says was what it must have been like to work with hands-on, visionary directors such as Alfred Hitchcock or Stanley Kubrick. "He was not so much a writer as the guy I had to please. So I would write all this stuff and he would say, 'I like this, I don't like this.' It was all sort of filtered through him. It's very much his work. We had a blast working together."

Clowes wrote "David Boring," his newest graphic novel, while he was working on the "Ghost World" movie. The book traces the operatic final months of a tortured 19-year-old security guard turned screenwriter who meets the girl of his dreams (she had a precursor, of course, a Nabokovian forbidden cousin in childhood) only to lose her to a cult. His quiet life gets progressively weirder, and after a variety of bizarre twists and gunshot wounds Boring winds up stranded on an island with his cousin as the world comes -- or does it? -- to an unclimactic end.

"I wanted the story to end with an explosion of happiness that was ultimately really depressing -- which is hard to do," says Clowes about his bittersweet ending.

"Stories come from whatever your psychological state is at the time of writing. A lot of it came from my situation of working on this movie. There's a lot of subtext about movies throughout the whole thing. I was working on 'Ghost World' with this female producer [Lianne Halfon] and Terry [Zwigoff], and we had this sort of family dynamic going the whole time. I was the son who was both the gifted genius and the ignored nobody. And I realized this producer was extremely hard to please. We'd do our best work and she'd find something wrong with it. And that all started coming out in these characters -- David's mother and distant father."

Boring is one of the few major Clowes characters who doesn't represent part of himself. "I was actually trying to create a character thinking, 'What if I had a kid? What if I had a son and he turned out to be like these horrible kids in Berkeley that I see every day -- these pot-smoking and skateboarding guys who listen to bad music?' I started thinking, 'God, I'd be so embarrassed! That would really be painful for me.' I thought, 'What kind of son would I like to have? Who would be a guy I would actually like?'"

Clowes was also thinking about the process of creating comics. "It's like these characters come alive from a kind of marriage between the cartoonist and the reader. And this merging of them is what created the character David Boring." He invented for David a mysterious, God-like cartoonist father and a cold, disapproving mother -- "sort of a stand-in for how I view the audience, as this cold, disapproving outside entity," he laughs.

The aesthetic that runs throughout Clowes' work seems to borrow heavily from a dim Chandler-esque vision of '50s urban decay and despair. The look has been described as "noir," but Clowes, who grew up on Chicago's South Side, says, "I grew up in a very urban neighborhood that had absolutely no qualities of suburbia, so I think my frame of reference was decaying old buildings and water towers, and it just all seeped into my consciousness. When I started drawing comics, and I thought about where a person would be walking around, it was like, 'Oh, a horrible-looking, graffiti-covered alley!' As a result, it seems like I'm trying to go for some kind of film noir look, but it's really just the world I'm familiar with." Even living in Berkeley -- which to Clowes is absolute suburbia -- for the past eight years hasn't influenced his vision. "When I close my eyes," he says, "I still see Chicago."

Clowes was born in Chicago in 1961, and his childhood was "perfect if you want your child to grow up to be a cartoonist." He was a "shy, loner, bookworm kind of kid" who liked to sit in his room and do comics. His parents, an auto mechanic and a steel-mill worker ("who made things in the basement in his spare time, including, for five years, stuff from the unassembled parts of an airplane -- the wings and part of the fuselage -- and a harpsichord"), divorced about a year after he was born. His father now makes furniture on commission, while his mother, who is 70, attends law school in Chicago.

"I remember never having got what had happened, and never having a sense of my parents' ever having been together. It was just this big mystery; nobody ever talked about it."

Clowes inherited his much older brother's bedroom along with a giant stack of comic books, long before he could read. Clowes remembers looking at them and trying to figure out what was going on in the stories and trying to decipher the coded message that his brother surely had left for him to unravel.

"I remember feeling like he was trying to tell me something -- as if by selecting these particular issues to buy, he was illustrating some psychological state. I was just picking this up intuitively. I always thought about it when I grew up. The comics all had these really specific images running through them that really haunted me."

When Clowes was 2 years old, his mother married a stock-car racer and opened an auto repair shop "in the worst neighborhood" on the South Side of Chicago. Not too much later, her new husband was killed in a race, and Clowes' mother sent him to live at his grandparents' house.

"I remember this big tumult as a kid. I had a long time during my childhood where I would spend each night at a different house, my dad's, my mom's and my grandparents'. It was really disjointed. It was a horrible childhood in that regard. It felt like I was in a suitcase. I remember a couple of times going to sleep at my dad's, and my mom would carry me to her house while I was asleep -- and I'd wake up at her house and be totally disoriented."

Clowes' grandfather, James Cate, was for three decades a professor of medieval history at the University of Chicago. His close friends included Robert Maynard Hutchins, Edward Levy, John Hope Franklin and Norman Maclean, and he was famous among students for his west Texas drawl and storytelling abilities. Clowes' grandmother was a "faculty wife" and the person to whom he was closest during his childhood. Clowes spent his summers at their house in Michigan, in a little cottage where there were no other people for two miles in any direction.

"That's where my imagination developed," he says, laughing. "I'd be playing with sticks and rocks, pretending they were my friends -- so if you want to turn your child into a cartoonist, lock him in a room with a bunch of sticks and rocks."

After graduating from high school, Clowes attended art school at Pratt Institute in New York. ("You've heard of it?" he asks, surprised.) He chose Pratt because "it was the only art school that had a dorm, and I couldn't afford an apartment in New York." Of his experience there he says, "I didn't learn anything, but my worst fears about art were confirmed -- that it was all about who you know and had a lot to do with having the gift of gab and being able to talk yourself into getting a gallery show and all that. I knew I didn't have that. So I trained myself to do what I wanted, which was to do comics."

His professors, many of whom he immortalized in the caustic and extremely funny "Art School Confidential" (which appeared in "Eightball" No. 7 and is the basis for the screenplay he is currently working on), were not supportive. "Every professor I had discouraged me and said, 'You'll never make a living from that; nobody cares, nobody will think of you as an artist.' And now I realize, when I look back on them, that they were absolute failures."

After art school, Clowes remained in New York and tried to get work as an illustrator. He would make a little money, then wait around for the next job. "It was hard. I started doing comics to keep my sanity. When Fantagraphics decided to publish 'Lloyd Llewellyn,' I was shocked."

"Lloyd Llewellyn," a '50s pulp-inspired private-eye parody series first published by Fantagraphics in 1985, was canceled after just six issues. "When 'Lloyd Llewellyn' was canceled," says Clowes, "I thought, 'Oh well, there goes my career.'"

He then started work on "Eightball," which was just the sort of multicharacter, multistory book he'd been wanting to do. "I thought, 'Well, here's my chance to do whatever I want, and nobody will buy it, but at least I'll do a couple of issues.'"

When issue No. 1 of "Eightball" -- which was then subtitled "An orgy of spite, vengeance, hopelessness, despair and sexual perversion" -- first hit the shelves in October 1989, its scathing, misanthropic indictment of the banal horror of American life was bound to strike a chord. ("I wasn't filtering myself at all. I was very depressed and I did the angriest, most obsessive stuff and, of course, it's what people responded to.") Though Clowes feels he was dragged "somewhat against my will into this youth culture/postmodern counterculture," he acknowledges that "there was a sort of zeitgeist going on and 'Eightball' spoke for people." If its nightmarish story lines weren't exactly exercises in realism, the queasy, unsettling feel of the series definitely reflected a collective sense of anger, resentment and dread. By issue No. 3, "Eightball" had caught on big.

When not railing at anyone who is not just like them, impaling frozen carp on their permanently erect penises, critiquing pure capitalism in "Richie Rich" parodies, running from their mothers or contemplating the ideal suicide scenario, the assorted freaks, misfits and misanthropes who populate "Eightball" spend a lot of time searching for their elusive ideal mate, often with horrific unintended results. Clowes has had experience with this, "though not in the past eight years." But he also thinks his characters' punishing search for perfection is somewhat of a metaphor (albeit, in most cases, unconscious) for "the endless frustration involved in trying to achieve that unnameable goal -- some combination of truth, beauty, perfection -- in my art."

"Eightball" has evolved, he says, to keep him interested. After having devoted much of the past few years to the apocalyptic story of "David Boring," the upcoming issue will consist entirely of two-page stories. "It's just gone through so many phases now. I've gone through probably five sets of readers. You get sort of identified with an era like that, and then that era passes and you have to either stick with it and hope it'll come back into vogue or go on your way and change a lot over time," says Clowes. "Different kinds of stories interest me. I think a lot of cartoonists get into something that they're really successful at and they stick with that, and then they're not that interested in it after a while and that comes through."

When fellow cartoonist Ware moved to Chicago in 1991, he was invited by Clowes and a group of other local cartoonists -- Gary Leib, Archer Prewitt and Terry Laban -- to join them in drawing improvisatory comics (which they called "minis").

"It was a welcome diversion, since I didn't really know anyone in town," says Ware. "Plus, I also got to see how they all worked, particularly Dan. It seemed as if he could draw anything, and whatever he did was always perfect -- not overdone, forced or uncertain. It all made me initially simply want to give up cartooning; but eventually I realized that I had to work much, much harder at it."

"'Eightball' is the greatest comic book of the last two decades," Ware adds, "and every issue is a huge step forward from the last -- which always seems to be an impossibility. I don't think that a statement like that can easily be applied to many other cartoonists' work. It's inspiring and comforting to know that he's always forcing himself to improve. His stuff makes the rest of us reconsider our own, and moves all sorts of subject matter that had seemed impossible before into approachable range."

Clowes is "painfully aware of the disregard and lack of respect that the rest of the world has for our chosen profession," Ware says, "but he also takes what he does very seriously. He once made me buy a huge book that lists hundreds of mostly obscure cartoonists, illustrated by self-portraits and hopeful autobiographies, which, he confessed, actually had made him get misty-eyed one day because of its undeniable grimness. I knew he wasn't kidding, as his eyes sort of went off in two different directions with the memory of it. He said I should have a copy so that he could call me up anytime and say, 'Look at Page 334,' and I'd know exactly what he was talking about."

Clowes' tortured but hilarious forays into self-exploration are well-documented in the pages of "Eightball," perhaps most brilliantly in the story "Just Another Day," in which young Clowes brushes his teeth, flosses, shaves and sniffs a dirty sock. The "real Clowes," who is directing this pathetic scene from a soundstage, interrupts the action to mock the reader and call his agent from his convertible. Then the "real real Clowes," who is drawing all this, is suddenly gripped by self-doubt -- he is really just a self-hating, sensitive "artiste" whose opinion of himself shifts with the breeze. This confession prompts the Operation Desert Shield T-shirt-wearing "actual really real Clowes" to come out and take charge. Or maybe that's not quite right. The story spirals into a hilarious slide show of possible identities. Who is Clowes? Is he a revolutionary? A scholar? A boring Midwestern cartoonist? A cross-dressing necrophiliac?

"It's hard to have any self-image when you do something like this, because I get no feedback for what I do until it's long finished. And then I don't really care. I'll work on something for six months just in this room, and I don't even let my wife read it. She has to read it when I'm not around and not talk about it or I get really angry," he says, laughing. "So I don't have any feeling of my place in the world; it's just like I'm living with this blank slate. Of course, I grew up thinking of myself as an outsider because I wasn't in the in crowd in high school like everybody else, but now I don't know what I'm in."

I get the feeling, though, that it doesn't really matter. In or out, the sense of discomfiture that permeates "Eightball" is all his own -- which is lucky for us, because if success hasn't spoiled Dan Clowes, total peace of mind just might.

So I'm somewhat relieved when he says, "You know, I'll get a call from the New Yorker or something, and I'll think I'm a big success! And then two minutes later I read a bad review and I think I'm the biggest loser! My wife goes crazy because I change so drastically. I'm like, 'Honey, we're rich! We can get whatever we want.' And then the next day, it's like, 'We have to really tighten our belts; my career is going down the toilet.'"

Shares