Before proceeding to the informational portion of this essay, please take a moment to complete the following questionnaire:

1) Are you disillusioned?

2) Disappointed?

3) Disgusted?

4) Disagreeably damp and jittery?

5) Are you worried you might have accidentally minimized your potential?

6) Are you trapped in a loveless cubicle?

7) Do you question authority when authority is out of earshot?

8) Does this fill you with shame and guilt and cheese puffs?

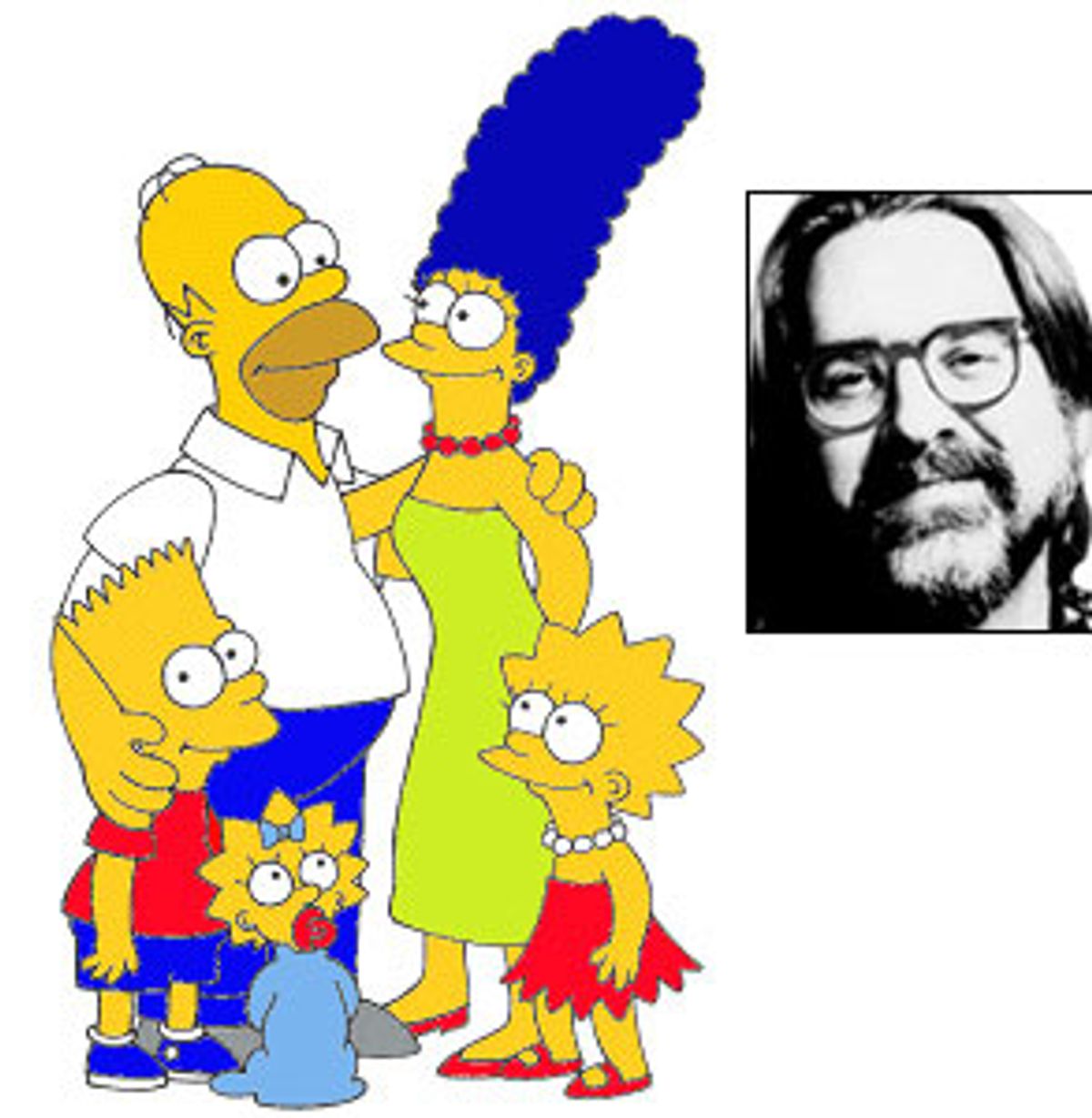

If you answered yes to one or more of the above questions, you are probably a fan of Matt Groening. If you answered no, you are also probably a fan of Matt Groening. Bush family aside, who is not a fan of Matt Groening? Ever since his syndicated comic strip "Life in Hell" -- that series of nihilistic but cuddly dispatches from the epicenter of gloom -- first appeared in 1980, Groening has been raising the dampened spirits of the fashionably alienated by dunking Binky, his rabbity, buck-toothed proxy, into a weekly bog of self-pity, anxiety and existential despair. As Flaubert might have said, "Binky, c'est tout le monde." But mainly, he is Matt Groening.

Or rather, he is the struggling, penurious pre-"Simpsons" Matt Groening. "I judge my life by how miserable it used to be," Groening told an interviewer last year, speaking of his early days as a lowly alternative cartoonist. "If I could pay my rent, I was deliriously happy. Now I'm deliriously happy all the time."

But before delirium set in, Groening spun a lingering bad mood and an "accidental" cartooning career into a billion-dollar print, broadcast, merchandising and licensing empire. Some seven years after Binky and his one-eared son, Bongo, first began delving into their epic disaffection, and the heroically insecure (but enterprising) gay twins Akbar and Jeff opened the first of their reprobate money-making "huts," "The Simpsons," the first animated series to hit prime time in 20 years, made its television debut.

His mission, Groening has said, was to create a sofa-centric sitcom about a typical American family and turn it upside down in retaliation for all the bad TV he watched as a kid. The message? "That your moral authorities don't always have your best interests in mind," he told Mother Jones magazine. "Teachers, principals, clergymen, politicians -- for the Simpsons, they're all goofballs, and I think that's a great message for kids." (Statements like these, of course, set off fits of right-wing apoplexy, much to the amusement and delight of everyone else. George Bush once famously regaled the nation with the suggestion that American families should aspire to be "more like the Waltons and less like the Simpsons," prompting Bart to retort, "But we're just like the Waltons -- we're both praying for an end to the depression.")

"The Simpsons" premiered in 1990, and eventually became the most popular, most widely broadcast and one of the longest-running shows in television history. "The Simpsons" has earned Fox's parent company, Rupert Murdoch's News Corp., well over a billion dollars, and its role in the network's growth has been incalculable. The show is watched by more than 60 million people weekly in more than 60 countries around the world -- beating out even the lowest-common-denominator friendly "Baywatch" as the world's most-watched show.

"Simpsons" executive producer Mike Scully, who took over as show runner, or head writer, in 1996, has said that in order to write for "The Simpsons," a writer must have "a healthy disrespect for everything Americans hold dear." And judging from the success of "The Simpsons," what Americans hold most dear is disrespect itself. Nowadays, you can't throw a rock at a TV set without hitting an irreverent animated social satire. But for a few brief moments in the early '90s, the idea that anything "alternative" could suddenly overtake the mainstream was still surprising. In 1991, the newly wealthy Groening still seemed to struggle with the central paradox of his career. "I'm a fan of counterculture -- of which there is very little right now," he told Fortune magazine. "What's happened is that mainstream culture has gotten so good at marketing pseudo-hipness that it overwhelms other choices that are out there."

Ten years later, at the age of 46, Groening is responsible for a comic strip syndicated in 250 newspapers, more than 25 books, two prime-time animated series and untold containers full of valuable merchandise. And for a guy whose career has been dedicated to skewering television, crass commercialism, "evil billionaire tyrants" (how boss Rupert Murdoch described himself in a cameo on "The Simpsons") and brainless consumers, Groening sure does love his merchandise. Images of "The Simpsons" have been licensed to sell everything from T-shirts to toys to potato chips to cheese, suggesting that mainstream culture has gotten pretty good at marketing genuine hipness as well.

Twenty-four years ago, Groening was just another unrecognized genius driving to Los Angeles in a crummy car with a coat hanger for a radio antenna. Sometime after midnight on the day of his arrival, his car stalled in the fast lane of the Hollywood Freeway in 100 degree heat. On the radio, a drunken DJ wept a final farewell to his job. It was Groening's first day in hell. So the story goes, and it has, as they say, legs. The broken-down car has alternately been described as a '63 Dodge Dart and a '72 Datsun. The details may vary, but the story, like most of the stories Groening tells about the defining moments in his life, reads like a fairy tale. This one is a Cinderella story: humble beginings, the insidious discouragement of petty authority figures, the unexpected intervention by fairy godproducer James L. Brooks and the eventual (stormy) marriage to a wealthy potentate (Rupert Murdoch's Fox network).

Groening grew up in Portland, Ore., with a father named Homer, a mother named Marge and sisters named Maggie and Lisa. In high school, he drew cartoons for the school newspaper until he was kicked off the staff. He ran for student body president on the "Teens for Decency" ("If You're Against Decency, What Are You For?") platform, and regretted his victory immediately. Later, Groening attended Evergreen State College in Olympia, Wash., which was known for its extremely liberal (no grades, no core requirements) liberal arts program. He befriended fellow cartoonist Lynda Barry and, finding no real authority to rebel against, he turned to cartooning in earnest.

Choosing Los Angeles because it was the place where a writer was most likely to be overpaid, Groening answered a "writer/chauffeur wanted" ad in the L.A. Times. Soon, he was driving an 88-year-old movie director around by day and ghost-writing his autobiography by night while living upstairs from a nocturnal rock lover (whose ceiling light he eventually dislodged with a plunging cinderblock). After graduating to a job at a record store called Licorice Pizza, whose gimmick it was to give away licorice to its customers (but whose employees often found themselves providing free licorice meals to the indigent instead), Groening began drawing "Life in Hell," a self-published, xeroxed comic book starring Binky, a lonely, alienated rabbit living in low-income Hollywood hell. Groening started sending the comic back home to friends in Portland in lieu of doleful letters about his miserable life. By installment No. 6, the list of recipients had grown from 20 to 500. "Life in Hell" was also sold in the punk corner of the store, where the punks sometimes ripped them up.

"I showed it to the editor of the Los Angeles Reader," he once told an interviewer, "and he hired me immediately -- to deliver newspapers." Groening worked at the Reader for six years, as a typesetter, editor, paste-up artist and rock critic. The paper offered him a cartoon strip in 1980, and, surprised, Groening accepted. "I never saw anything as crude as my stuff getting published," he has said.

Six years later, after Groening penned an angry letter to the editor over the dismissal of a writer, the paper fired him by replacing his strip with another cartoonist's work while Groening was out of town on a book-signing tour for "Work Is Hell." Groening found out the way everybody else did, by picking up the paper. By then, however, "Life in Hell" was running in several other alternative weeklies, and soon the L.A. Weekly brought him on board. In 1987, Groening married fellow Weekly staffer Deborah Caplan. A few years earlier they had set up their own syndicate, ACME Features, to distribute the strip. A self-published anthology of "Love Is Hell" led to a deal with Pantheon Books, and eventually Caplan began running Life In Hell Inc. The goal of the company, she told Newsweek, was to "keep the machine of Matt going." (After 13 years of marriage, Caplan filed for divorce in March 1999, the same month as Groening's second show, "Futurama," premiered. They have two sons, Homer and Abe, now 13 and 10.)

In the mid '80s, renowned producer James L. Brooks approached Groening about using the characters from "Life in Hell" on a new show he was developing for comedian Tracey Ullman. Groening knew this would have meant losing ownership rights to his characters, so he decided to start from scratch. As Groening told Spin magazine. "Who knew if this TV thing would pan out?" Needless to say, it panned out.

Groening's success owes as much to his own work as it does to the work of a slew of others, including co-creators James Brooks and Sam Simon, and "The Simpsons'" writing staff. Though Groening has continued to churn out his comic strip every week, it's been about a decade since he wrote an episode of "The Simpsons." The daily task of writing the show is left to a team of writers, whom he calls his "Harvard-grad-brainiac-bastard-eggheads." In fact, when "Simpsons" writers wax elegaic, they tend to do so about George Meyer, a writer who first became involved with the show late in 1989, a few months before its Fox premiere. Executive producer and show runner Mike Scully once told the New Yorker, "People are always asking why 'The Simpsons' is still so good after all these years, and, at the risk of pissing off all the other writers, I think I'd have to say that the main reason is probably George." Ian Maxtone-Graham, another writer on the show, has said in an interview, "I would rather make George Meyer laugh than get an Emmy." Groening has said that due to his limited drawing ability, it's unlikely he could get a job as an animator on "The Simpsons" today. Perhaps, were he to walk in off the street, he could get a job as a writer on the show. But in any case, Groening allowed the series to evolve under the tutelage of his writers, the undisputed champions of television comedy.

Brooks' and Simon's hand in shaping the show was significant. It was thanks to Brooks' reputation that "The Simpsons" was granted a level of autonomy not normally given to television shows -- especially one as risky as "The Simpsons" seemed at the time. Simon was also responsible for hiring the writing staff, who shaped the characters into what they are today.

In the 10 years since the debut of "The Simpsons," however, Groening had gone from semifamous alternative cartoonist to iconic powerhouse. A fan of science fiction, he had been thinking about creating a show about the future for some time. And the idea of creating a show on his own appealed to him. "I think Matt likes the fact that this is more his baby," Rich Moore, supervising director of Rough Draft, the company that animates "Futurama," told Spin magazine. "That there's no Jim Brooks around. I think he kind of wants to prove, maybe to no one but himself, that he can do it without those guys."

"Futurama" moved away from the family sitcom structure and into dysfunctional workplace territory, a subject that had long inspired Groening. A thousand years in the future -- a wry, bleak version of a future where suicide booths and celebrity heads preserved in jars are part of the landscape -- work is still hell. The show centers on Fry, a pizza-delivery man who is accidentally frozen in a cryogenics lab and defrosted 1,000 years later. He winds up working for an intergalactic delivery service, with a crew of misfits including Leela, the ship's one-eyed alien captain and Bender, a corrupt, vice-addled, disgruntled robot. Needless to say, the life-affirming executives at Fox worried that the show was too dark and negative.

Despite the unprecedented success of "The Simpsons," the process of getting "Futurama" on the air has been described by Groening as "the worst experience of my adult life." When he and former "Simpsons" show runner David X. Cohen (now the show runner on "Futurama") first approached Fox with the new idea, the network went into instant paroxysms of ecstasy. Then, no sooner had they ordered 13 episodes than the doubts set in. The network resisted giving Groening the autonomy he needed and plied him with notes. As to the autonomy he'd enjoyed with "The Simpsons," Groening was told, "We don't do business like that anymore."

Not that Fox isn't grateful: "If you go back 10 years ago, we didn't have a lot of successful shows on the air," 20th Century Fox Television co-president Gary Newman told Daily Variety in January 2000, about nine months after the debut of "Futurama." "To many divisions of this company, 'The Simpsons' was the shining light that kept us motivated and believing that our division would grow. What may never happen again is another show that comes along and had the overall importance to a particular company like 'The Simpsons' has had for News Corp."

Groening was outspoken about his criticisms of Fox's business practices and its inexplicably shabby treatment of him and his new show. "I guess I shouldn't have been surprised, because this is how everyone is treated [in Hollywood]," he told Mother Jones. "But I thought I would have a little bit more leeway since I made Fox so much money with 'The Simpsons.'"

Sharing one inane series of meetings, he told the magazine, "I said, 'Look, I told you "Futurama" is not going to be bland and boring like "The Jetsons." And it's not going to be dark and drippy like "Blade Runner." And they said, 'Don't make it like "Blade Runner"!' I said, 'It's not going to be like "Blade Runner."' They said, 'Make it like "The Jetsons"! You know, "Meet George Jetson. His son Leroy."' And I said, 'I think it's Elroy.' They said, 'It doesn't make any difference!'"

The pilot episode of "Futurama" was scheduled to air in the coveted slot between "The Simpsons" and "The X-Files" on Sunday night, and was watched by 19 million viewers. Then Fox moved "Futurama" to Tuesday night, and audiences fell to about 8 million. The show, according to Groening, was "buried." Eventually, it was moved to Sundays at 8 p.m., but although Fox recently ordered 18 more episodes for next season, Groening, thinking like the businessman that he is, still feels the show could benefit from more aggressive promotion and a better time slot.

Still, it's clear that Groening's satire feeds on frustration and the stupidity of others. Were it not for the clueless executives, the inane network decisions, the petty betrayals at the hands of people who benefit from his success, he might have stagnated by now. Despite his status as an ultimate insider, Groening's writing has always been that of an outsider. In interview after interview, he has recalled his youthful vow never to forget what childhood was like -- a gauntlet of petty rules and restrictions that exist only to be broken. When he's not telling the Cinderella story, the story Groening tells about himself is a David and Goliath story; and the older and more powerful he becomes, the bigger and more powerful the lumbering naysayers standing in his way. From teachers who forced him to rip up his cartoons in front of the class, to the petty tyranny of bosses ("I was told that I would never get a job in the Pacific Northwest in journalism after my disgraceful stewardship of the Cooper Point Journal," Groening told the graduating class in a commencement address at his alma mater, Evergreen State College. "Hey, they were right!"), to the narrow mentality of newspaper editors (even "alternative" newpaper editors "hated" his approach to obscure rock criticism) to the "timidness" of network executives trying to subject him to "corporate deflavorizer," to his famous battles with network censors, Groening's life reads like a series of epic adventures more Quixotic than Homeric in their details. He casts himself as the avenging underdog tilting at windmills, but, in the end, he always returns the conquering hero.

Groening's position is an interesting one for a satirist to find himself in. He made a name exploring his own alienation and a fortune exposing the absurdities and hypocrisies of our culture, and nowadays, Groening is as powerful an insider as they come. Groening is a guy who lunches with Rupert Murdoch and finds him congenial. And yet he speaks like the kid who just made it big, who still can't believe his luck. "Do people who don't have cockroaches and can afford their rent, are they happier?" he said in a Mother Jones interview. "I wake up every morning thinking how lucky I am."

When asked by Mother Jones if he has ever considered funding "noncommercial enterprises," he responds, "I knock myself out as a commercial artist, and people come to me all the time with proposals for money-losing endeavors ... I like the idea of trying to be successful on some level, at least reaching an audience enough so that you can sustain it and keep on going." As to his position on the "Simpsons" voice actors' recent contract negotiations, he told Mother Jones, "I have sympathy. They are incredibly talented, and they deserve a chance to be as rich and miserable as anyone else in Hollywood ... Hold out for as much money as you can get, but make the deal."

Groening himself has always made the deal. "The success of the show," he has said, "has gone beyond my wildest dreams and worst nightmares."

Shares