It's 1977 and Fleetwood Mac is the biggest Mac in the world. The band's "Rumours" album has been No. 1 on the American charts for 31 weeks. Stevie Nicks' husky baby voice, all velvet and helium, pours forth from every turntable and car window in the land: "Thunder only happens when it's raining/Players only lo-ove you when they're playing." You can't escape "Rumours." After a while, you don't even try. You simply lie down in the tall grass and let it do its stuff.

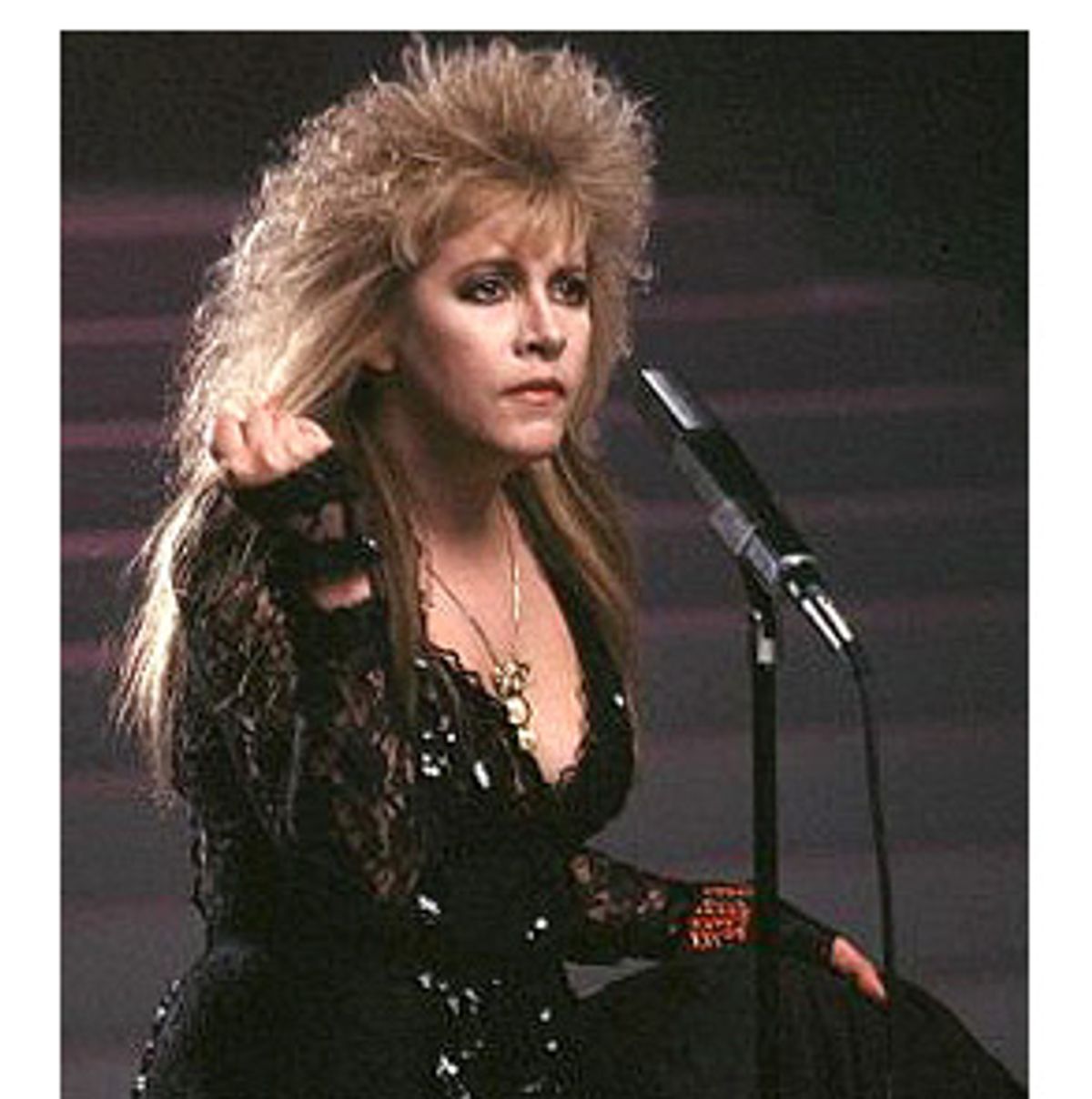

Nicks is one of Fleetwood Mac's three singer-songwriters -- keyboardist Christine McVie and guitarist Lindsey Buckingham are the others. But onstage (and Fleetwood Mac is touring incessantly), Nicks is front and center, tiny and snub-nosed and as fresh-faced as a cheerleader, twirling in her ballerina skirts and gauzy batwing blouses and lacy shawls and Bride of Frankenstein platform boots. She's the photogenic one, and the media gloms onto her, which isn't fair, really, because Fleetwood Mac is much more than Stevie Nicks' backup group.

Drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, the band's namesakes, are one of the most supple, crackling rhythm sections in rock 'n' roll; they've anchored Fleetwood Mac through years of personnel changes, and now they've made their big, unimaginably big, score. The latest incarnation of Fleetwood Mac has a luscious sound merging the smoky blues favored by Christine McVie with the American pop-folkie confessionalism of Buckingham and Nicks, two kids from affluent San Francisco suburbs who played in a local band together, ran away to Los Angeles, became lovers and recorded one unsuccessful album as a duo. The album nonetheless caught the ear of Mick Fleetwood, and they joined the band in 1974.

In Fleetwood Mac, Christine and Stevie are like the Dashwood sisters in Jane Austen's "Sense and Sensibility," although not in the way you'd assume. McVie is an accomplished, respected musician. Her singing is self-possessed and serene. But she's the one writing vulnerable lyrics like "You can take me to paradise/But then again you can be cold as ice/I'm over my head/And it sure feels nice," and "Oh Daddy ... I'm so weak but you're so strong." Nicks has the flighty, passionate image of a girly-girl pirouetting in a fairyland of crystal visions ("Dreams") and snow-covered hills ("Landslide"); onstage, she pulls her velvet cloak around her and becomes "Rhiannon," the sensuous witch who "rings like a bell through the night" and "rules her life like a bird in flight." But her love songs are tough and clear-eyed and almost always about the ends of affairs. She does the leaving, and the getting even. She does not beg. McVie and Nicks are a beguiling contrast, and between them stands the intriguing, intense Buckingham, half tempestuous rock stud, half needy little boy. This is a band.

But as great a band as Fleetwood Mac is, it's the romantic entanglements of its members -- during the recording of "Rumours," Nicks and Buckingham were breaking up, and so were the McVies -- that got them on the cover of Rolling Stone, all in one big bed together. And you have to admit, the Nicks-Buckingham oil-and-water coupling, chronicled in the songs they wrote to and about (but, oddly, never with) each other, is in itself worth the price of admission.

Their split is captured in the greatest he said/she said single of all time, "Go Your Own Way"/"Silver Springs," released in 1976. "Tell me why/Everything turned around/Packing up/Shacking up is all you wanna do," Buckingham writes, rather ungallantly, in the fevered "Go Your Own Way." In "Silver Springs" (which was left off "Rumours"), Nicks hits him with a spine-tingling curse: "I'll follow you down till the sound of my voice will haunt you/You'll never get away from the sound of the woman that loves you." (Twenty years later, Stevie will sing that song in Fleetwood Mac's MTV reunion special, her calm, level gaze fixed unwaveringly on Lindsey. Chain, keep us together.)

Yes, it's 1977, and Stevie Nicks (born Stephanie Lynn Nicks, in Phoenix) is the most popular, most visible, woman in rock. And she's a joke. Rock critics (East Coast, male) call her an airhead, a fluffball. "Stevie is a California girl prone to writing songs about witches, mysticism and all the other shit one would conjure up sauteeing in a Jacuzzi ... But although Big Mac's sound has been consistently bland, you can't blame Stevie -- she's tried to provide some comic relief," goes one review from Creem. But punk is coming and it's gunning for mega-ultra-supergroups like Fleetwood Mac. A new generation of women rockers will rise and they will play unpretty, untwirly music. Nicks' reign will soon be over. In the future, she and Fleetwood Mac will be a footnote, a footprint frozen in the tar pits of the bloated corporate rock age.

And coffee will never cost $3.50 a cup, LPs are here to stay and California will never, ever run out of electricity.

It's 2001 and it's OK to admit it now: Stevie Nicks is cool. Actually, she's more than cool -- she's hot. Girl group du jour Destiny's Child samples the chattering, buzzing rhythm track from Nicks' post-Mac hit "Edge of Seventeen" on "Bootylicious," a song from their chart-topping CD "Survivor"; Nicks appears in the video. Courtney Love is a fan; so is Smashing Pumpkin Billy Corgan. (Love and Corgan covered Nicks' "Gold Dust Woman" and "Landslide," respectively.) Disciple Sheryl Crow produces, plays guitar and sings on five of the 13 songs on "Trouble in Shangri-La," Nicks' first album in seven years. Other members of Lilith nation -- Sarah McLachlan, Macy Gray, Dixie Chick Natalie Maines -- sing on "Trouble in Shangri-La," too. Even Nicks' '70s glam princess look ("For me to be without it would be like Gypsy Rose Lee without her boa," she once told an interviewer) is back in style, resurrected in recent collections from fashion designers Isaac Mizrahi, Jill Stuart and Oscar de la Renta, among others.

On the cover of "Trouble in Shangri-La," Nicks is wearing something fluttery and flappy; her feet, in those platform boots, seem to barely touch the ground. Photographed from behind, she looks like she's about to fly off a castle balcony over the moonlit ocean. What's the matter -- all your life you've never seen a woman taken by the wind? Back in Fleetwood Mac's day, they called Stevie a witch and snickered at her and feared her whirly-girly, hit-making, mystical female powers. But wouldn't you know it, witches are cool now, too: Willow and Tara from "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," the sisters on "Charmed," Tabitha on the soap "Passions." Stevie Nicks was, of course, ahead of her time.

You can see why empowered females like McLachlan and Crow are lining up to pay their respect. There has always been a warm sisterliness about Nicks' music. OK, sometimes you don't know what the heck she's talking about, but she has never penned an unkind word about another woman. Nicks is a girl's girl. She always has a posse of female friends around her; female fans used to perm their hair and wear flowing shmattes in her honor. She was unselfconscious enough to write a love song called "Sara," and let people wonder.

When "Sara" came out on Fleetwood Mac's dense 1979 "Tusk" album, there was a theory going around that the song was about Bob Dylan's ex-wife, sung from Dylan's perspective. And though that theory has been debunked by Nicks herself, it remains a tantalizing possibility. Isn't it obvious that Nicks is a Dylan-head, always has been? Listen to her phrasing, her verbose, opaque, myth- and legend-referencing lyrics. Of course, nobody knows what Dylan's talking about sometimes, either, but nobody ever called him an airhead.

But I digress. The women in Nicks' songs are free birds and gypsies, in tune with the moon and the sea, independent, unafraid to be alone, uncaged. In the manly world of rock 'n' roll, Nicks articulated a yearning female spirituality. She put her womanliness right out there, undiluted. She was Lilith Fair before there was Lilith Fair.

Today, at 53, Stevie Nicks is still twirling. Her voice is deeper and slightly more nasal -- a byproduct, maybe, of the gigantic hole in her nose that resulted from her long coke habit (well documented on a particularly juicy episode of VH1's "Behind the Music"). But the new maturity in Nicks' timbre gives her "Trouble in Shangri-La" duets with Crow, Maines and Gray a more fascinating texture. All of those women have a bit of Nicks in them -- Crow has her husky-throated introspection, Maines her sugary toughness, Gray her slinky eccentricity. So when they take turns singing with Nicks, it's as if you're hearing her past and present selves meeting up to ponder what was, what is and what might have been.

Indeed, one song on "Trouble in Shangri-La," "Planets of the Universe," was written in 1976 while Nicks was breaking up with Buckingham. You can hear echoes of "Silver Springs" in the chorus' fierce prediction: "You will never love again/The way you loved me." She's still worrying that knot, and so apparently is Buckingham, who plays guitar on the track "I Miss You." Either that, or he's a really good sport.

"Trouble in Shangri-La" is Nicks' best work since her 1981 solo debut, "Bella Donna." The record is full of purpose and spark, and Nicks has found a symbiotic producer in Crow, who gives her tracks an elegantly crisp, country-folk/Beatles-pop sound -- she's like Buckingham, without the baggage. Although Nicks didn't write all of it, "Trouble in Shangri-La" is pure Stevie, with songs called "Sorcerer" and "Candlebright" and lots of womanly wisdom about not regretting the past and embracing age and being true to your dreams. Nicks is a middle-aged girl getting her second wind. She has never apologized for being Stevie Nicks, for doing those interpretive dances, for wearing those boots, for never learning to read or write music.

She has outlasted the bad reviews ("A menace solo, equally unhealthy as role model and sex object," wrote Robert Christgau in the '80s edition of "Christgau's Record Guide"). She has outlasted the cocaine addiction, and the addiction to the tranquilizer Klonopin, prescribed by a doctor to help her kick the cocaine addiction. She has outlasted the Epstein-Barr syndrome (caused by degenerating breast implants, she believes) that left her exhausted, bloated and creatively blocked. She has outlasted the depression and the self-doubt: "Will you write this for me/He said, No, you write your songs yourself," she sings on the new "That Made Me Stronger," about a pep talk she got from her old pal Tom Petty. But Stevie Nicks won't outlast "Rhiannon," "Landslide," "Dreams" and "Silver Springs." Those songs -- those melodies, that foggy, headstrong voice -- play on and on, woven into pop music's genetic code. You'll never get away from the sound of the woman who wrote them.

Shares