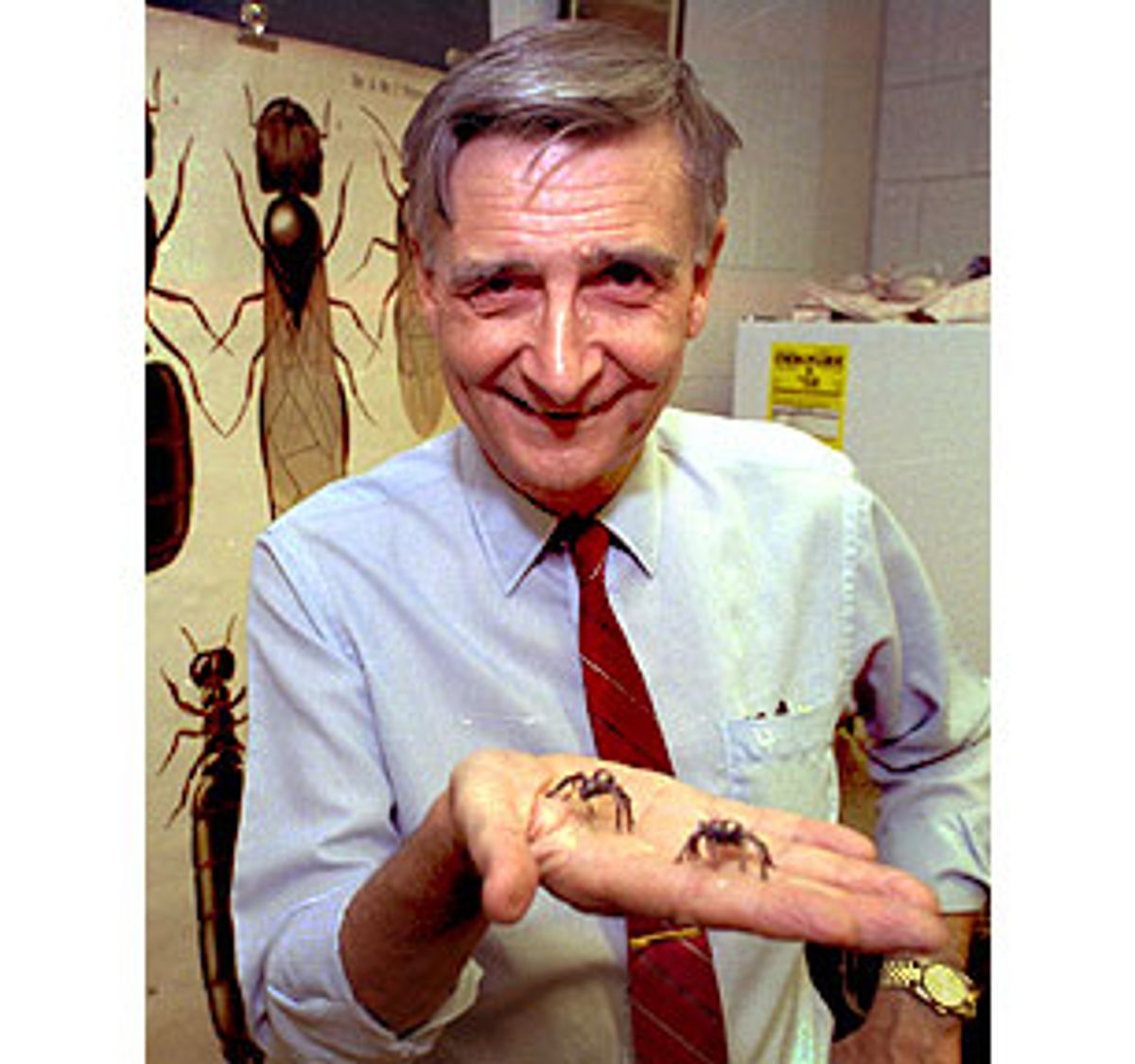

Edward O. Wilson, born in 1929, began his career as a scientist and while still young became a tenured professor at Harvard specializing in myrmecology, the study of ants and their social systems. He was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Jimmy Carter in 1977, and he has won the Pulitzer Prize twice -- for his books "On Human Nature" and "The Ants." Over the years, Wilson has achieved the unusual status of unofficial societal wise man, an elder consulted on a wide variety of human affairs.

Wilson's belief that the hope of humanity lies in traditional religionists adopting more science and environmentalists appealing more to humankind's spiritual impulses comes at a crucial moment for the environmental movement. The hard truth is that the condition of the environment is far worse on Earth Day 2000 than it was on the first Earth Day in 1970.

But it is Wilson's willingness to venture into public policy and to apply the insights of science to a wide variety of human affairs that has brought him the most public attention. He has played a seminal role in alerting policymakers and the public to the crisis of declining biodiversity. Arguing that humanity is living through the greatest mass extinction of plant and animal species in 65 million years, he has done perhaps more than any other single person to spur action to preserve biodiversity around the planet.

Wilson is also unusual among scientists for his emphasis on the importance of the spiritual impulse, both as an evolutionary advantage central to human nature and as a key to hope for the future. Yet his career has not been without controversy. His 1975 book "Sociobiology," which argued that human behavior was profoundly affected by our genetics, spurred left-wing critics to accuse him of thinking linked to genetic determinism and racism. In a famous incident described in his memoir, "The Naturalist," critics poured a pitcher of water on his head at a Washington conference.

Time heals most wounds, however. The rise of evolutionary psychology in the 1990s, and Wilson's softening of some of the hard edges in later editions of "Sociobiology's" final chapter, have largely vindicated his approach. The sum total of his life's accomplishments has made him one of America's most respected thinkers.

Despite the work done by the environmental movement over the past 30 years, the condition of the environment seems to be getting worse.

That's true. You could say that the rate at which it's being degraded has maybe been slowed a little bit as a result of the environmental awareness that we have. But it's continuing downhill.

You've said that if the environmental movement is to succeed it must go beyond its present focus on simply making the environmental argument and somehow join the environmental case to the spiritual impulse which you've described as central to human behavior and one of our most powerful drives.

I also agree with a lot of other environmentalists that to put the price tag on future products that may come from the wild environment and the ecological services that the wild environment gives us -- as impressive as these figures may be -- is potentially disastrous. Because they leave the impression that the wild environment, the place we live and to which we're so very well adapted, can be bought and sold on the market. And obviously there's vastly more to environmental consciousness than that.

To what extent is increased suffering or even the disappearance of the human species threatened as you look out over the next century?

I'm pretty sure the human species will survive, but in what condition is very uncertain. The key problem is that while a certain percentage of the Earth's population will be able to cocoon itself and maintain a very high standard of living, the rest of the population will have a serious problem due to overconsumption.

What's giving way most rapidly in the attempt to raise quality of life in the developing world are the natural environments. The experts on natural resources around the world are in pretty much complete agreement that the world population as a whole is running down arable land, and the trend shows no sign of being reversible. Also, fresh water is declining around the world, with many of the aquifers scheduled to give out in the next several decades. The forests, estuaries, coral reefs, river systems and, increasingly, even the oceans are being either destroyed or seriously degraded.

So there appears to be no solution to what may be the final Malthusian limit for 8 billion people, which is about where we'll be in two decades, almost all of them striving for the greater consumption that everybody greatly desires for themselves and their families. It's obvious that the key problem facing humanity in the coming century is how to bring a better quality of life -- for 8 billion or more people -- without wrecking the environment entirely in the attempt.

You're known for alerting the world to the biodiversity crisis, which you've said is the greatest mass extinction in 65 million years. What's really at stake here? Is this simply an issue where humanity will miss out on certain medicines that might have been discovered? Or are we really talking about a phenomenon that could lead to the destruction of the human species?

Again, it's not going to result in the destruction of the human species. But the worst-case scenario is that by the end of the century we would be living in a still changing and increasingly hostile physical environment. We would have an impoverished world with great inequities remaining in quality of life and an enormous opportunity cost for what we've done in the 21st century.

By opportunity cost, I mean that whole libraries of potential scientific information disappear with each species. And a wide range of products -- many of our future pharmaceuticals, new crops that are badly needed especially for marginal areas, new sources of fibers and other products that will come from biotechnology and gene transfer in agriculture and animal husbandry -- will be lost. And therefore there'll be a very substantial economic opportunity lost in destroying the environment.

But there's a lot more to the ill effects of habitat destruction than just opportunity costs. There's also the opportunities that the ecosystems give us for free.

Such as?

Such as the cleansing, availability and continuous supply of water, and the renewal of soils. This is an art that 3 billion years of evolution has perfected, but that we haven't even begun to think about properly as a single dominant species modifying everything. And providing the very air we breathe, all free of charge.

It's very important to keep in mind, while considering ecosystem services, just exactly what is happening to the world and what the essence of environmentalism is. This planet is not in physical equilibrium like the other solar planets. It's in a shimmering disequilibrium that comes from vast arrays of species and plants and animals and microbes living on a thin film. The biosphere that envelops the planets is so thin that it cannot be seen, edgewise, from an orbiting shuttle. This film modifies and holds the physical environment of the world in a very special equilibrium. It does this by maintaining quite complex and sophisticated cycles of energy and materials transport. And the human species is exquisitely adapted to that particular environment that the biosphere had in place when we first came along.

We did not descend into the biosphere as angels to occupy it. And we are not visitors from outer space who have colonized Earth. We are an animal species, very special, but an animal species nonetheless, that evolved in the biosphere. This is the cradle to which the human species was born and to which we are very finely adapted physically and psychologically. So when that special environment is modified in any way, the Earth becomes very much more fragile and unstable, and the future of the human species is increasingly at risk. This is the naturalistic view of how the world works that most scientists who are concerned with the environment share. It puts things in perspective.

The truth of the matter is that all the changes we make render the planet less suitable, not more suitable, for human beings. It's a fundamental distinction to be made between scientific environmentalism on the one hand and nonscientific, ideological- or religious-based anti-environmentalism or indifference on the other. This is what arguments about the environment -- as they are still with us at this Earth Day -- basically consist of.

If the spiritual impulse is central to reversing this state of affairs, we need to understand it more. Why is it so central to who we are? Why do we have so many religions?

That it exists is beyond any doubt. But exactly why we have these deep feeling and tendencies to render sacred the things most important to us is far from settled by evolutionary psychology, biological or social studies of the human mind.

But we can make some guesses: for instance, that we are intensely religious because we are intensely tribalistic. If there's anything characteristic about the history of humanity going back into deep time, it is that human beings have lived in tight clannish groups, whose members are often related to one another -- and their relationship is kept close record of -- and they are in competition with, and often hostile to, neighboring groups.

So to have the deep-seated biological, neurological impulse to draw together into the clan, particularly in times of stress and conflict, is highly adaptive. It also provided added likelihood that the group, and therefore the individuals in the group, will survive difficult times. So tribalism is surely a major element.

What's the connection between tribalism and the belief in an external God or a spiritual-religious impulse?

The way to make something sacred, or the way to give yourself the self-confidence and ability to risk individual lives on behalf of the group, is to assume the presence of a superior being that most likely created that particular group and certainly gives it superior knowledge and validity in the world. Those are the characteristics of tribes. That seems to be a principle that both anthropologists and biologists would agree on as one source of religious or spiritual impulse.

But that's only the beginning. This aspect that I've dealt with to some extent -- and I feel that this is not studied nearly enough generally -- is what I call biophilia. That is the innate tendency to affiliate with, and draw deep satisfaction from, other organisms -- specific ones, certain species that we fixate on, certain habitats that we recognize as home based and also certain environments and settings that we recognize as ideal habitation.

There's no doubt anymore, from psychological tests, that people do prefer a natural environment in which to live. They want to have also a substantially modified environment for their habitation -- and to provide food and protection. But then, beyond that and given a choice, the vast majority of people -- allowed to develop freely in their psychological preferences and where they go and what they experience -- do prefer access to a natural environment. Clearly this is something very deep and very mysterious in the human psyche, and very important for human welfare.

In your book "Consilience" you say that consciousness is evolved from the material. But you also use the word "sacred" a lot. When most people use the word "sacred," they're usually talking about an external, nonmaterial God. How do you use the word "sacred"?

It's true that the word "sacred," strictly used, is assumed to be connected with the supernatural in some sense. That may take the form of divine intervention from a single creator God, or something as diffuse as the spirits of trees and rocks, a kind of sacred quality of nature.

The naturalistic view, though, requires that we consider the broader meaning of the sacred: the deep sense of spirituality about each other and about our natural environment. And to sacralize, to make sacred, is in my view the end product of evolution in our moral and aesthetic reasoning. It proceeds from mere preference and liking, to custom, to ritualization, to law, all the way to ascribing that behavior or perception to a profoundly important source.

How would you define the word "spirituality"?

You're about to turn me into a philosopher [laughs]. Spirituality in my mind is a sense of awe and wonder. A combined sense of awe and wonder and mystery that comes from the perception of, or belief in, something that exists in the world that is very important to us to the point of being given special status in our everyday lives. And it's protected by custom and ritual and law.

You've called for "devising a new spirituality based on what we actually know about our own origins across millions of years of evolution, and thence on into our historical origins," or what might be called a human-based spirituality or religion. One of the basic purposes of traditional religion has been to provide us with a sense of meaning and purpose. Under a human-based religion, how would individuals feel a sense of meaning and purpose if it isn't to go to heaven and sit at the foot of God?

You're asking me a very particular personal question. You've just given a reason why I'm active in the humanist movement -- which is a relatively small population of people in the United States. I'm always impressed by the fact that there are something like 5,000 members -- and there are 15 million Southern Baptists alone. This tells us something about how the mind works. It doesn't necessarily serve as a means of figuring out which belief cuts the deepest.

And humanists -- I'll identify myself as a secular humanist -- recognize that they do not have 2,500 years of the evolution of ritual and mythology into which they can invest their spiritual energies. That's the easy way. Humanists recognize that there's another way. It's harder and it's not undergirded by a long history of sacralization. And it may never have sacred prayers and sacred hymns.

But it will instead provide a substitute, based upon an understanding of how the world works, that in time could grow stronger than the support and psychological strengths provided by traditional religions. One thing that is apparent now is that most religious mythologies are poor descriptions of how the world works. So in effect they are fallacious. And this shakes one to the extent that one wishes to hold onto a traditional religious view.

What has become clear is that as far as we can work out -- with all the science and technology and reconstruction of history that we are capable of -- the world is very different from the vision of traditional religion. And far more complex, far larger, far vaster, far more interesting in many ways.

The human species -- in achieving its independence from that universe, its ability to survive in good part by understanding how the universe works -- has achieved something truly magnificent. And what we need to offer in the way of reverence should be not to some imagined higher power, but to each other. And we need to dedicate ourselves to preserving the one home -- seemingly the only home -- that we're ever likely to have as a species. And that brings us full circle back to just what this world consists of in terms of a very particular disequilibrium that has taken billions of years to evolve.

You're saying that the purpose of life under a human-based religion is first to show reverence to each other and all life on Earth and, second, to preserve life? That would be the purpose of this new human-based religion?

Yes. Thanks for putting it so succinctly.

One of the major functions of religion over the millenniums has also been to provide humans some comfort in the face of their deaths.

That's one other powerful source of religious belief. It's a way of dealing with our own mortality. We're the first species, the only ones, to understand our personal mortality. Actually we have a powerful motivation to want to rationalize ourselves into immortality. The way that's done in traditional religions is through the promise of paradise and everlasting life. And the way it's done in naturalistic circles is by identification of ourselves more closely with our species and our planet.

If you look out over the next 50 years, how do you personally find comfort or deal with your own intimations of mortality?

That's very easy. When you talk to most thoughtful humanists, they agree that once they've gotten over their idea of personal immortality, they're freed. It's an enormously liberating experience in one sense, now giving you a whole new set of guidelines by which to live your life. And at that point you start measuring the value of your life according to what you can give back to humanity and to the long-term future of life on Earth.

This would place a great importance on caring about future generations. But in your article "Is Humanity Suicidal?" you present what you call the dour scenario that "people place themselves first, family second, tribe third and the rest of the world a distant fourth. Their genes also predispose them to plan ahead for at most one or two generations." To what extent do you believe that that's not just a dour scenario but actually true for humans -- that we have a lot of trouble thinking four, five, six generations out?

Unless people make an extraordinary effort, they're aware and concerned about only a relatively small number of people and for a relatively small number of generations. And this, of course, is more easily acceptable if you have a traditional religious point of view -- you're concerned with the disposition of the immortal soul. But if you have a naturalistic viewpoint, you don't believe in an immortal soul. Therefore where you can put your most altruistic impulses and best reasoning is the physical and physiological welfare of future generations.

But if the evidence thus far is that we have trouble thinking out more than two generations, is there any evolutionary basis to think that humanity can make the transition to looking five, six, 10 generations out?

I think so. By reasoning. By building scenarios in our mind and actively cultivating an authentic ethic of the welfare of future generations, not just talking about it.

Let's try to make a distinction between what your mind and heart would tell you. In terms of pure intellect, if you were an analyst who came here from another planet, would you feel humanity is suicidal? That we don't have much chance of existing the next two, three, four, five hundred years?

No, I don't think we're suicidal at all. My favorite quotation is from Abba Eban, the Israeli political leader. In 1967, when everything seemed to be insane in the Middle East he said: "After all else has failed, men turn to reason." So we do have these wonderful, deep innate impulses to preserve the tribe. That can be expanded to mean humanity and the rest of the biosphere. And we do have a powerful and extremely ingenious set of emotions and psychological devices to look after our children and our grandchildren. We can extend that to an indefinite number of generations.

In other words, these universal, ethical impulses do not countervail what we already have built within us. And by the same token we can take the best of our religious and spiritual impulses -- the awe and aesthetics and sense of mystery -- and expand them beyond the ordinary confines or traditional religions to encompass our continued exploration of the universe and preservation of the planet as our home.

Given that we have only 5,000 humanists and 15 million Southern Baptists alone, how can one envision the growth of a human-based spirituality quickly enough to make a difference in saving the environment?

That's easy: through the secularization of traditional religions. Already most of them accept the idea of evolution. Already most of them accept that the human mind really does have a physical basis. And, furthermore, most of the Abrahamic religions of Islam and Christianity have shown themselves very prone to the conservation ethic when the information is made available to them. There's a very strong green movement in Christian sects at the present time. So that is part of the evolutionary process.

What I see in the future is not some kind of mass conversion to the humanistic position. The best in people will still be manifested in traditional religions as they have been. But traditional religions will evolve in a secular direction until finally what most people will live by will be a naturalist view, even if it is not fully humanist. Certainly the fellowship of religions today are extremely liberal by historical standards.

What personally gives you hope as you look out over the next century, and what inspires you to do this work?

Well, I think every person wants to have a life that is generous in outlook and contributes something of value to the future. And in my case, the conservation and restoration of the natural environment is an extremely satisfying activity. I really can't say more than that. It's a worthy effort, it's worth hard work and constant thinking. And the rewards are very substantial for all of these reasons we've been discussing concerning the value of biodiversity.

In your book "Biophilia" you mention your visit to Cuba just before Fidel Castro's Moncado invasion and his "history will absolve me" speech. You suggest that he and all of us will likely be judged by history more on our environmental behavior than anything else.

Yes, I think we should look at the world that we're in and what we're leaving to future generations very much with conservation in mind. One thousand years from now, even just 100 years from now, people will judge us far more than we now dream of for the amount of the natural environment that we either destroyed or left intact for them. They're not going to be emotionally involved anywhere as much as we are with today's wars, epidemics and great economic problems. I think they will judge us by how much of the natural environment, and the remainder of life in the natural environment, that we have left them. Because that is the one thing, the one heritage, that cannot be modified, whether it is generous or unfeeling and stingy.

If I'm the average American and I say, in effect, "Look, I understand what you're saying, but the truth of the matter is all I really feel for is my own life and the people I know. I just don't feel any concern for future generations. I hope they live well, but it's not my concern." How would you respond?

I would say, "I don't believe you." I think the average person is a lot better than that. And I would add, "I hope you'll be an environmentalist. The cost is not great. And the payoff is enormous, even in your own time."

Could you give any more of a case for why my life would be enriched by caring about future generations?

I think I better leave it at that. I've probably been way too preachy already [laughs]. Your average reader has got enough in him or her, there's enough of an environmental mood in this country now, that they're going to know what we're talking about. You've been very nice, but you've led me off into the fever swamps of theology.

Well, I got there because it seems that the environmental movement's present reliance on environmental and technical arguments is not enough. The environment is getting worse. And even a politician like Al Gore, who clearly understands the crisis, has not made it a major issue in this campaign. Polls suggest that the environment is not a voting issue in the election. It seems that unless we can touch the spiritual impulses within us that care about future generations, we will not do what is necessary to save them.

I completely agree. I think we have to work on this aspect of it. This is the reason why I'm not dismissive of even the most fundamentalist among the religious. I'm not being cynical about it. I think they have wonderful impulses that can be added to the environmental movement.

Are you saying that scientists should seek a dialogue with traditionally religious folks and say in effect, "Look, let's not argue about what we disagree on, let's focus on what we can all agree on"?

Those are almost the same words I use in the last paragraph of my book "The Diversity of Life." That's how I close it.

It seems that unless the environmental movement can tap into people's largely unconscious feelings of spirituality, mystery, awe and reverence, and then tie it to concern for future generations, we're not going to save the environment.

The centerpiece of my new book is going to be what you just said. I think we've got to get moving on this. I don't think it is something that's going to be done in a humanistic ivory tower. It's got to be done in a way that touches what people like Joe Six-pack are thinking. We've got to get moving on an effort to spiritualize the environmental movement -- not in the sense of starting to offer up prayers -- but with a sound empirical base.

Shares