Axl Rose has hit his own fans with glass bottles, told Jon Bon Jovi to suck his dick, compared Indianapolis residents to "prisoners in Auschwitz" and canceled concerts without warning. He has also paid out more than $1 million in legal settlements. Critics have labeled both him and his music racist, homophobic and asinine.

Many of Rose's former boosters now consider him a crybaby, an OK singer who cares only for himself and is unable to act his age. His two wives divorced him over claims of mental and physical abuse, while Slash, his former Guns n' Roses partner in crime, hasn't spoken to Rose in almost a decade. His fans aren't much kinder -- long before Guns called it quits in 1993, they'd started calling the band "Guns n' Poseurs," and when Rose returned to the stage last year in Las Vegas, most of the Guns faithful focused less on the music, and more on Rose's expanded waistline.

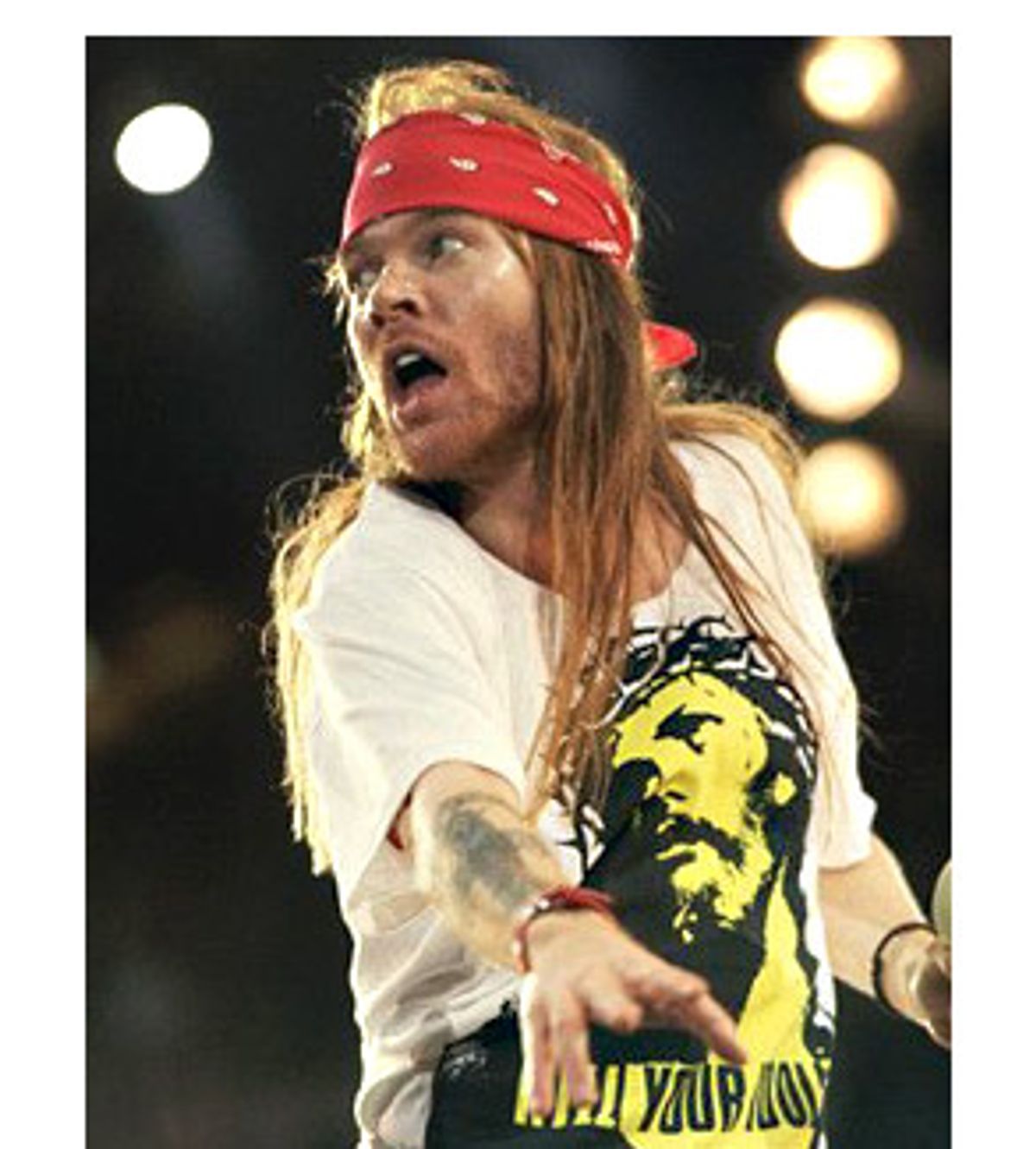

But forget all that. Rose's personal problems, legal travails and general immaturity can never overshadow his talent. Axl Rose kicks ass. He descended on the '80s like acid, burning holes in a country that had become culturally complacent. For anyone with angst, anyone who grew up under Reagan-Bush, hating suspendered suits, hair-spray rock and synthesizers, Axl Rose was a savior. His angry, paranoid lyrics, piercing screams and stomping stage presence all acted as antidotes for the made-up go-go conservatism of the time. He was the anti-Culture Club hero, the flat-haired, bandanna-clad bad boy who never played by the rules, never tried to look pretty -- the one guy who repeatedly made people listen, then told them to fuck off. Few rock 'n' rollers -- Johnny Rotten in his prime, Kurt Cobain -- have given the world a more sincere dedication to pure, authentic anger.

No one could have seen it coming. Rose, born Bill Bailey on Feb. 6, 1962, in Lafayette, Ind., enjoyed most of his boyhood without incident. He grew up in a strict Pentecostal home, but didn't seem to mind much, singing in the church choir and working around his mother's rule that no rock 'n' roll be played in the home.

Then, at 17, he discovered that his natural father -- a man named William Rose -- had abandoned the family when his son Bill was 2. Rose suddenly started to lash out. School and church mattered less and less and he began getting in trouble with the law. The infractions were minor -- shoplifting, public drunkenness -- but they foreshadowed the future.

They also led to Rose's flight. Fed up with Midwestern mores, he hitchhiked to Los Angeles in 1980 with dreams of rock stardom in his head. He soon hooked up with another Indiana native, guitarist Izzy Stradlin, and two other musicians, guitarist Tracii Guns and drummer Rob Garner. The latter pair left Guns n' Roses after the band failed to get a record contract, leaving room for Slash, drummer Steven Adler and bassist Michael "Duff" McKagan to join.

This second draft of Guns n' Roses had more luck, and released its first album in 1985, a live EP from Geffen Records called "Live ?!*@ Like a Suicide." The band's official entrance into the pantheon of rock, however, came two years later with "Appetite for Destruction." Here, it seemed, was something different. Guns rocked somewhere between punk and metal; fast but approachable, it drove listeners just crazy enough to keep returning for more. Even now, the album still hammers a nerve, selling an average of 9,000 copies a week, according to SoundScan.

Some credit for success should be shared. Slash, in particular, played an important part in forging Guns' hard-driving style. But while the songs were supposedly written by all members of the band, the lyrics reek of Rose. And more than anything else it's Rose's delivery -- the squelching engine of rage -- that makes Guns n' Roses unique.

Rose simply attacks the music. I'll never forget throwing on headphones and walking to seventh grade with "Appetite for Destruction" in my Walkman. Rose made me blast the volume and pick up the pace. He didn't so much sing as scream and I couldn't help yelling with him. By the time I got to school, I had beads of sweat on my forehead and a distinct desire to take over the world, to make it listen -- to be, no matter what anyone said.

It wasn't just the big hits -- "Sweet Child o' Mine," "Paradise City" and "Welcome to the Jungle" -- that grabbed me and so many other teenagers. It was the songs that never ended up on the radio, the songs that injected adrenaline into our lives, the songs with (gasp!) swear words.

Take "Out ta Get Me." Never mind that the song simply mixes tired Old West outlaw ideas with a guitar-heavy assault of sound. Never mind that it leads directly to Rage Against the Machine's "Fuck you/I won't do what you tell me." And forget the fact that Rose's paranoia may or may not have been justified. Just listen to the words:

"They're out to get me," Rose sings several times. "They won't catch me/I'm fuckin' innocent/They won't break me."

Talk about a contagious chorus. Who hasn't felt such paranoia at some point in his life? Who hasn't felt so wrongly accused that he wanted to scream? Who hasn't wanted to declare, "They won't touch me 'cause I got somethin' I been buildin' up inside"?

And yet, it's not just the content that's magnetic; it's also the development, the performance. Rose, at his best, can rival Robert De Niro playing Jake LaMotta in "Raging Bull," or Al Pacino in "Serpico." Rose draws you in with his sway, his simple wardrobe of jeans, T-shirt and a red bandanna -- and then he makes you watch and listen as he edges closer and closer to the abyss.

It's all the more exciting to experience because Rose moves so quickly between acting enraged and actually doing damage. Seeing Rose live is a "never know" proposition. You might see the best show of your life, or you might get three songs and the middle finger. But Rose will never put on a concert that's merely routine.

The mix of the sinister and the righteous seems too intense for Rose to suppress. The bitches' brew has only grown stronger over the years. "Lies," for example, Guns n' Roses' second album, which came out in 1988, contains several songs that twist contradictory emotions into a rough, intriguing thread. "I Used to Love Her" tells the story of what sounds like a murder, yet it's widely considered a song about Rose's dog -- which he loved but had to euthanize and bury in his backyard. "Patience" preaches virtue in ballad form, but Rose breaks down in the end; and then there's "One in a Million."

The hateful, six-minute rant filled with lines like "immigrants and faggots don't mean much to me" brought hailstorms of criticism. Yet it sounds a lot like a parody of the late-'80s political mood. Once you overlook the sheer offense of what Rose screams, which is no easy task, the song looks more and more like a documentary of discontent, the preface to the white male backlash that we now acknowledge exists thanks in large part to Susan Faludi's book "Stiffed."

Rose's later career seems to support the theory that he's not so much ignorance incarnate as he is perpetually immature. Writing last year in Rolling Stone, critic Peter Wilkinson may have said it best when he noted that Rose is "a complicated man who can be sensitive and funny but who is also controlling and obsessive and troubled."

Fame in particular seems to have changed Rose. By 1990, only three years after "Appetite for Destruction," he burned out. He didn't show up for studio sessions, cut concerts short and tended to be reclusive when he wasn't throwing temper tantrums. He even scared off his wife Erin Everly, who married Rose in April only to divorce him nine months later. She also accused him of beating her, which Rose denies.

Regardless, the music seemed to suffer. "Use Your Illusion I and II," and "The Spaghetti Incident" -- an album of cover songs, including one written by Charles Manson -- lacked the tight mix of sound and fury. There's a bit too much vengeance here, toward the press, toward fans and mostly toward women. Rose and the band spend too much time and energy settling scores. "Oh My God," the only song released by Guns since Rose and Slash parted (while Rose secured the band's trademark), also feels stilted.

But even in the midst of the mess, while Rose went through another rough relationship, this time with model Stephanie Seymour, and then found himself trampled by "alternative" rock, more lawsuits and depression, Guns managed to bang out a few gems. Rose may have been right last New Year's Eve when he told an audience, "I have traversed a treacherous sea of horrors to be with you here tonight," but throughout his rise and fall he has never lost his volatile brilliance.

It's the rawness of Rose that forms the core of his appeal. He may be a lot of things -- a brat, a prima donna, a seriously troubled, violent man -- but one thing he's never been is a fraud. He's always had his own look, his own vocal style, his own attitude and his own agenda. In the rock 'n' roll marketplace of the '80s and of today -- when consumers are given a choice only between overproduced pop and overproduced nü metal -- the sheer honesty of Axl Rose stands out. He's always given the world a piece of his mind. And for that, some of us will be forever grateful.

Shares