George Harrison was my favorite Beatle when I was the age when you have favorite Beatles. For a shy kid lurking on the edge of teenagerdom, the skinny, quiet Harrison was the perfect moptop to adopt. The two big guys were too obvious; John was too brash and Paul was too pretty. There was Ringo, but for some obscure reason the fact that he was the drummer worked against him. Besides, he was cute in a way that in sixth grade was strictly for the girls, and he had what looked disturbingly like a 5 o'clock shadow.

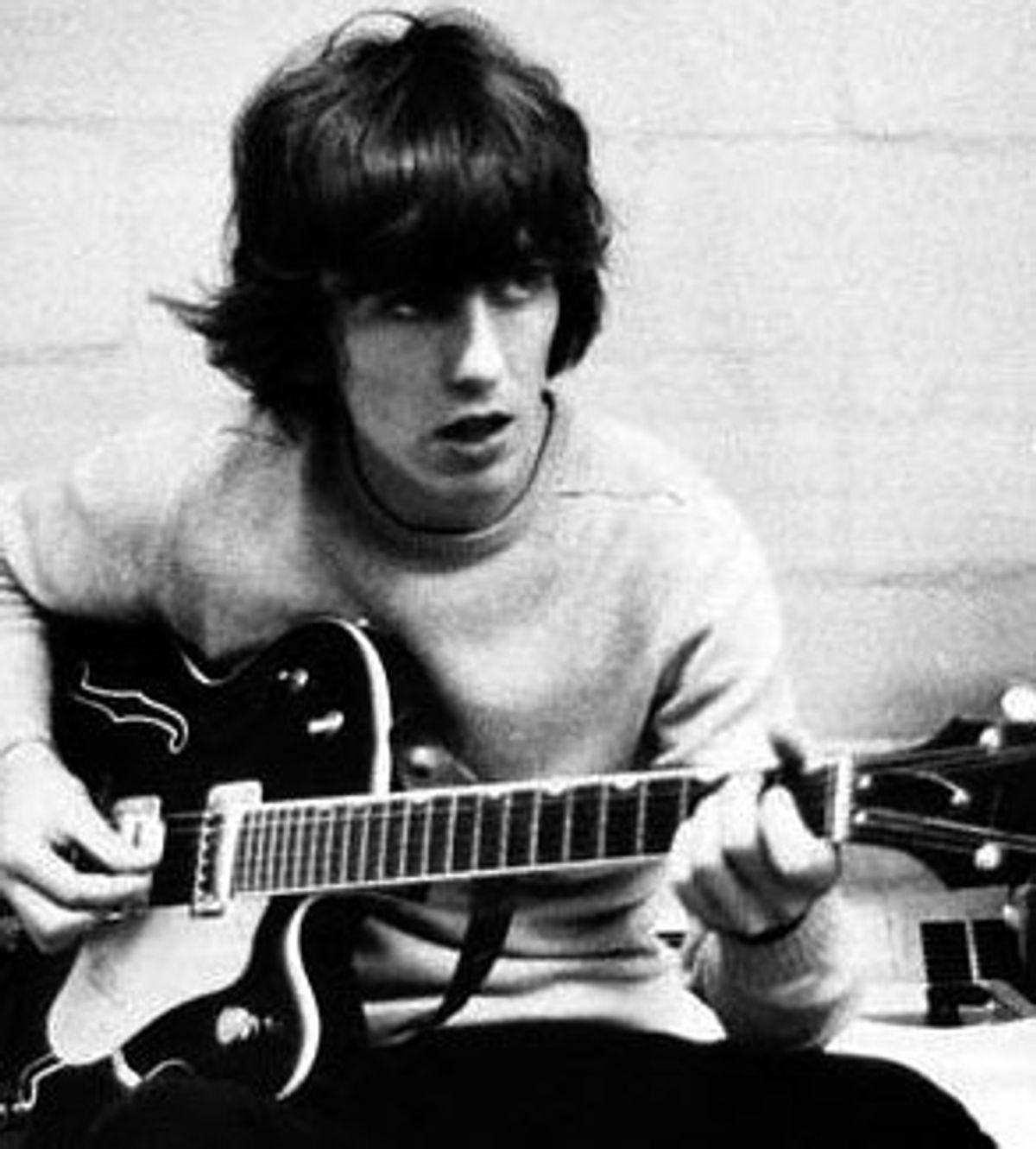

George, by contrast, seemed aloof and innocent and mysterious -- and young. He wasn't entirely boyish -- there was some hint of mastery about him, some vaguely unnerving sense of sexual knowledge in his lean face -- but he definitely came off like the junior partner in the band. On the cover of "Meet the Beatles," the first record I ever bought, he looks like he's about 16 years old -- which wasn't that far from the truth. He was the kid who was accepted into the club: the perfect wish-fulfillment icon.

And he played lead guitar. At the time, I barely knew what that meant, but I figured it must mean he was a better instrumentalist than his gaudier big brothers. While Paul and John were busy being geniuses and stars, I imagined George in the background, hunched over the neck of his guitar like a writer hunched over his typewriter, quietly and painstakingly adding the notes that would make the songs John and Paul wrote even better.

But George didn't stay my favorite Beatle for very long. Partly this was because he was so much less incandescent than John and Paul that idolizing him felt almost perverse, self-consciously eccentric: It was like choosing to memorize Rosencrantz's speeches instead of Hamlet's. All the great songs, all the great vocals, were by John and Paul. "Don't Bother Me," the first Harrison composition to appear on a Beatles album, was a nice song, and his voice had a slightly nasal, sensitive thinness that was endearing, but it wasn't memorable enough to thrust him into the limelight. His guitar playing and backing vocals sounded good, but you didn't really notice them. If you were going to have a favorite Beatle, and you weren't making your choice on the basis of sexiness or deliberate obscurantism, it had to be John or Paul. George just kind of fit in.

The real reason George didn't stay my favorite Beatle is that as I listened over the years, it became clear that the Beatles couldn't be taken apart. They were indivisible. It was the Beatles, not John or Paul or George or Ringo, that my generation grew up with; it was the Beatles that, for a host of sometimes inexplicable reasons, created a soundtrack that so many of us lived by. I couldn't have a favorite Beatle any more than I could have a favorite parent or a favorite child.

And it is as a member of the Beatles -- nothing more, nothing less -- that we will remember George Harrison. "He fit in" does not appear to be much of an epitaph -- until you remember that what he was fitting into was the greatest rock group of all time.

Say "lead guitar" and you don't think of somebody fitting in -- you think of somebody soaring off, opening their id like a firehose and blasting away everything in the vicinity. This is the mainstream guitar-god rock legacy, from Mike Bloomfield to Jimi Hendrix to Eric Clapton to Van Halen to Allan Holdsworth. This wasn't Harrison's style. Blinding speed was never his specialty, though he could lay down nasty licks with the best of them. And in his entire career with the Beatles he probably never took longer than a 30-second solo. But what Harrison brought to the Beatles was exactly what the Beatles needed.

Harrison remains a seriously underrated guitarist, but even to call him a "guitarist" feels wrong. He played the songs, and the guitar was what he happened to use. As a soloist, he had a beautifully clean melodic style, one almost completely devoid of the blues-riff clichis that almost every rock guitarist falls back on. He was a master of sophisticated chord voicings and gorgeous intros, like the roaring, cascading opening guitar line in "And Your Bird Can Sing." He was disconcertingly versatile: from the tricky pick-and-fingering country-twang Chet Atkins style of some of his early work, to the sitar and tamboura experiments on "Norwegian Wood" and "Within You Without You," to the gut-shaking straight rock in "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart Clubs Band (Reprise)."

But his signature style (which the above solos share in -- Harrison had an identifiable voice from the beginning) is unclassifiable: It's the orchestral approach found on songs from "Fixing a Hole" to "Tomorrow Never Knows," an osmosis-like style in which the phrasings soak up the musical context like a sponge. Many of Harrison's solos sound like they were worked out in advance. This can sometimes take away from their sense of spontaneity, but it gives them great depth and subtlety. He played guitar like a composer, unhurried, willing to use silence, making every note count: He himself retreats until he becomes almost invisible, and what is left are musical passages that are so perfectly crafted that it is impossible to imagine them any other way.

Harrison was also an exceptionally gifted and varied songwriter, whose light was somewhat obscured by the supernovas he kept company with. His Indian-mystic efforts never quite sent me into whatever empyrean they were intended to, but the soft poignancy of "Here Comes the Sun," the muscular empathy of "If I Needed Someone," with its great chiming 12-string chords, and the satisfyingly nasty rant "Taxman" bear witness to a talent that at its best stands comparison with Lennon and McCartney. I don't know whether he had in him more than the two or three songs he was allotted per album or not (most of his post-Beatles work seems to indicate he didn't), and I don't really care. "Rubber Soul" and "Revolver" and "Beatles '65" and all the rest are his legacy, along with that of his mates, and they will do.

Above all, Harrison epitomized taste -- a commodity we don't readily associate with rock 'n' roll. He knew how to listen. He was a consummate team player, both as a calming influence on the stormy Lennon-McCartney sea and as a creative collaborator. And when dozens of his peers who ran off those pyrotechnic solos are long forgotten, George Harrison will still be there, deeply ingrained in songs that in their honesty, their strangeness, their enduring loveliness, will form his permanent epitaph.

For those of us who grew up when the Beatles were the very face of invincible youth, George Harrison's death, like that of John Lennon so many tragically long years before him, is inevitably a memento mori. The shock and pain of Harrison's passing is not as great as Lennon's, of course: Lennon was cut down at 40, and his murder ended the dream -- the illusion -- that the era of the Beatles could somehow go on forever. Dying of cancer at 58 is different. Yet something of the same pain, a pain mixed with an old wonderment, is stirred by George's death -- because in some corner of our hearts, he will always be George, that shy, fearless boy whose unlined face looked out at us so many years ago. So when we're thinking about it all we will ask each other: Do you remember the opening chords of "Getting Better"? Do you remember that bit when he comes wailing in at the end of "Got to Get You Into My Life"? And when the tears come, as they will for many of us, they will be tears not just of sadness but of joy, of a profound gratitude.

Shares