Roger Vadim, who died in Paris on Feb. 11 at 72, was the classiest exploitation filmmaker who ever lived. That's not intended to belittle the director, as some of the American obituaries that have appeared seem bent on doing. (If you read Alan Riding's obit in the New York Times you might wonder what's worse: death or having your life summed up by this guy.) Probably no screen purveyor of gratuitous female flesh has ever been so blithe, so beguiled by the leading ladies who paraded nude through his movies. The fact that those women were frequently his wives (Brigitte Bardot, Annette Stroyberg, Jane Fonda) or mistresses (Catherine Deneuve) might help to explain Vadim's unique brand of exhibitionist tenderness, but I think there's another reason: Vadim adored women.

His first film was called "And God Created Woman" (1956), and Vadim photographed his stars like a man who never stopped giving thanks to the Creator. The director George Stevens once said that CinemaScope was good only for shooting snakes and funerals. Vadim proved him wrong with the glorious shot near the beginning of "And God Created Woman" in which a sunbathing Bardot stretches out across the wide screen. It may be the most famous shot in all his movies (helping to get it condemned by the Vatican -- always a good sign) and the most emblematic. It's frankly voyeuristic (as is a later shot where Bardot rises nude from her conjugal bed, shielded by the transparent sail of a model boat) but without a trace of smirking or leering. There was no grossness or vulgarity in Vadim. He may have been a voluptuary, but he was a discreet one. He may have been a Svengali, but he gazes at his leading ladies more like Casanova than Don Juan.

Vadim wasn't a great filmmaker. His plots are often trivial, and when he took a turn toward the fantastic, as in "Barbarella" (1968) and "Don Juan, or if Don Juan Were a Woman" (1973), the results were often ludicrous. Even in his heyday Vadim received very little critical respect. He wasn't reworking the form of movies as were his contemporaries, Truffaut, Godard and Rivette, and so, in contrast, he seemed easily dismissed. It may be that American critics, working under our native assumption that "European" equals "art" (and, to be fair, working in an extraordinarily fertile period for foreign movies), didn't know what to do with a foreign director who was unabashedly commercial. And then there's the traditional critical blind spot: the inability to make a case for what gives us pleasure if it can't be defended as art.

Or the inability to see the virtues of a filmmaker who is casual about his craft, who isn't preoccupied with filmmaking. Vadim's movies are relaxed, not obsessed. Their sexiness is like being immersed in a warm bath. There are no great revelations here, no philosophy that goes deeper than partaking of the sensual pleasures life offers. You get the feeling that if Vadim had been told he could never have made another movie, it would have been fine by him, that there were plenty of other things for him to enjoy. But that capacity for pleasure is at the heart of the pleasure his movies give.

Vadim's movies reveal the eye of a natural filmmaker. His cinematographers vary from movie to movie and so the consistent clarity of his compositions makes it pretty clear that their pictorial instinct was Vadim's. The vistas of the Mediterranean in "And God ... " and the Spanish mountains in 1958's "The Night Heaven Fell" (both of them recently released in restored, wide-screen videos by Home Visions Cinema) are postcard-pretty but also attuned to the distinctive quality of light and air, to each climate's particular brand of heat. Bardot scandalizes the locals in the former by sunbathing nude. But the "amorality" that the Vatican saw in Bardot's wild child-woman (with exquisite irony, the same thing the blue noses in the movie condemn) seems like a natural response to the setting. A hedonist of superb taste, Vadim was drawn to locales of both natural beauty and indolent sensuality. (It's no accident that his 1984 American remake of "And God Created Woman," starring Rebecca DeMornay, is set in Santa Fe.)

The most vivid setting of the Vadims I've managed to see (many, like "Circle of Love" or "The Game Is Over," both with Fonda, have been unavailable here for years) is in "Blood and Roses," his 1960 film of the Sheridan Le Fanu vampire tale "Carmilla." Part of the movie was shot on the grounds of the Emperor Hadrian's villa, and Vadim and cinematographer Claude Renoir (the nephew of Jean Renoir) surround it with misted wintry light. Even in the disgraceful video available from Paramount (a pan-and-scan job taken from a terribly faded print) the eerie delicacy of the movie's look comes through. The dialogue is often stiff and the acting (by Mel Ferrer, Elsa Martinelli and Vadim's then-wife Stroyberg as the vampire Carmilla) worse. But that stiffness gradually takes on the feel of somnambulance and the movie achieves some of the fragmented lyricism of the great silent horror films. Mood is everything here, and it pays off in a dream sequence that's a startling piece of Gothic modernism, like what Cocteau might have come up with if he'd surrendered to the high-fashion erotic perversity of Helmut Newton.

Sex, of course, is what sold Vadim's movies, though most of them are exceedingly decorous. Vadim was naughty, not shocking. If, for critics, "foreign" equals "art," Vadim's movies recall the days when, for couples looking for an acceptably titillating evening out, "foreign" equaled "sexy." Which may be why his 1973 "Don Juan," starring Bardot (in her last role) as a female version of the seducer as destroyer, feels so lost. Coming out in the era of porno chic, when it was OK to discuss "Deep Throat" at suburban dinner parties (as in a memorable scene from Philip Roth's novel "American Pastoral"), the movie is Vadim's attempt to live up to the new era. But his heart isn't in it, and the movie, complete with a pot-party orgy that's as silly as most movie orgies, is gaudy, false to his decorous taste. The scene where Bardot takes Jane Birkin to bed was much touted at the time, but the two do little more than cuddle (and Vadim rather primly focuses on their feet). Even his most famous film, "Barbarella," is best summed up as racy.

"Barbarella" sounds like such a good time -- a sci-fi sex comedy scripted by (among others) Terry Southern and starring Fonda in a role Vadim described as "a sexual 'Alice in Wonderland'" -- that discovering how bad it is remains one of my biggest movie letdowns. The cheap visuals make it appear to be taking place in a sound-stage vacuum, and the execution is not only flat-footed but at times (when evil mutant children set dolls with razor-sharp teeth upon Barbarella) inappropriately unpleasant. The movie, though, is a validation of the faith Vadim put in his leading ladies. Fonda's delicious performance periodically guides Vadim to amusing comic-book carnality. When Fonda proved herself a great dramatic actress a few years later with her roles in "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" and "Klute," "Barbarella" was held against her, proof of the frivolity she'd left behind. Fonda's performance, though, is one of the sexiest comic performances in the movies. She's the square-jawed American hero transformed into an all-American sexpot, Buck Rogers with an itch in her knickers.

But the original "And God Created Woman" is the movie that still best sums up Vadim. The plot is pure melodrama -- Bardot inveigles an inexperienced innocent (Jean-Louis Trintignant) into marriage to escape being sent back to reformatory, though she still resents being jilted by his stud older brother. But unlike most movie melodramas, this one didn't omit the sex. The familiarity must have been reassuring to audiences, a turn-on that didn't threaten them. Frangois Truffaut summed it up (with the enthusiastic overstatement that made his criticism so lively) when he said the film was "simultaneously amoral (rejecting the current moral system but proposing no other) and puritanical (conscious of its amorality and disturbed by it)." It is, of all things, a movie about a young couple who learn to love each other through the joys of marriage. (The same is true of the DeMornay remake, a bad, but sweet mixture of soap and soft-core sex. And it appears to have been true of Vadim's life. He was reportedly a good papa who loved to cook for his four kids, and at the time of his death he had been happily married to his fifth wife, actress Marie-Christine Barrault, for 15 years.)

It's undeniably conventional -- Bardot learns to respect her husband when he becomes man enough to take charge -- and it's a bummer that Trintignant expresses his anger over Bardot's dalliance with his brother by slapping her. But the movie is rooted enough in recognizable sexual archetypes to not be a total concoction. It's not so farfetched to think that a timid husband would find self-confidence by discovering he's capable of giving his wife sexual pleasure, or that a spouse's jealousy would be a turn-on to a cheating partner.

Most of all, "And God Created Woman" is a happy case of a born movie star being brought to the screen by a born filmmaker. Bardot and Vadim had begun an affair when he was 21 and she was 15, and he'd begun to mold her into a starlet who caught the attention of the press. What she does in the movie isn't acting (that would have to wait until her heartbreaking performance in Godard's 1963 "Contempt"), but it's transfixing. Bardot is a walking overabundance of everything -- hair, curves, lips. So much has been written about Bardot the sex kitten that it's worth saying that her appeal in the movie has something of the appeal James Dean had in "Rebel Without a Cause," though without Dean's neurotic neediness. Bardot has a thoughtless insolence that gets you immediately on her side. When she comes down to the wedding banquet wrapped in a sheet and appropriates for her husband the lunch her new mother-in-law has laid out (he's waiting in bed upstairs), or when she refuses to defer to the snooty customers she encounters at her boring job, she's the triumph of instinct over duty, of youth over everything fusty and stale. The clichi invoked over and over to describe Bardot in the film was a wild animal, and there's an element of truth there. Seeing her walk away after sloughing off the chastisement of some authority figure is like watching your cat walk out of the room after you've scolded it: They both move with the deliberate provocation of a creature who couldn't care less.

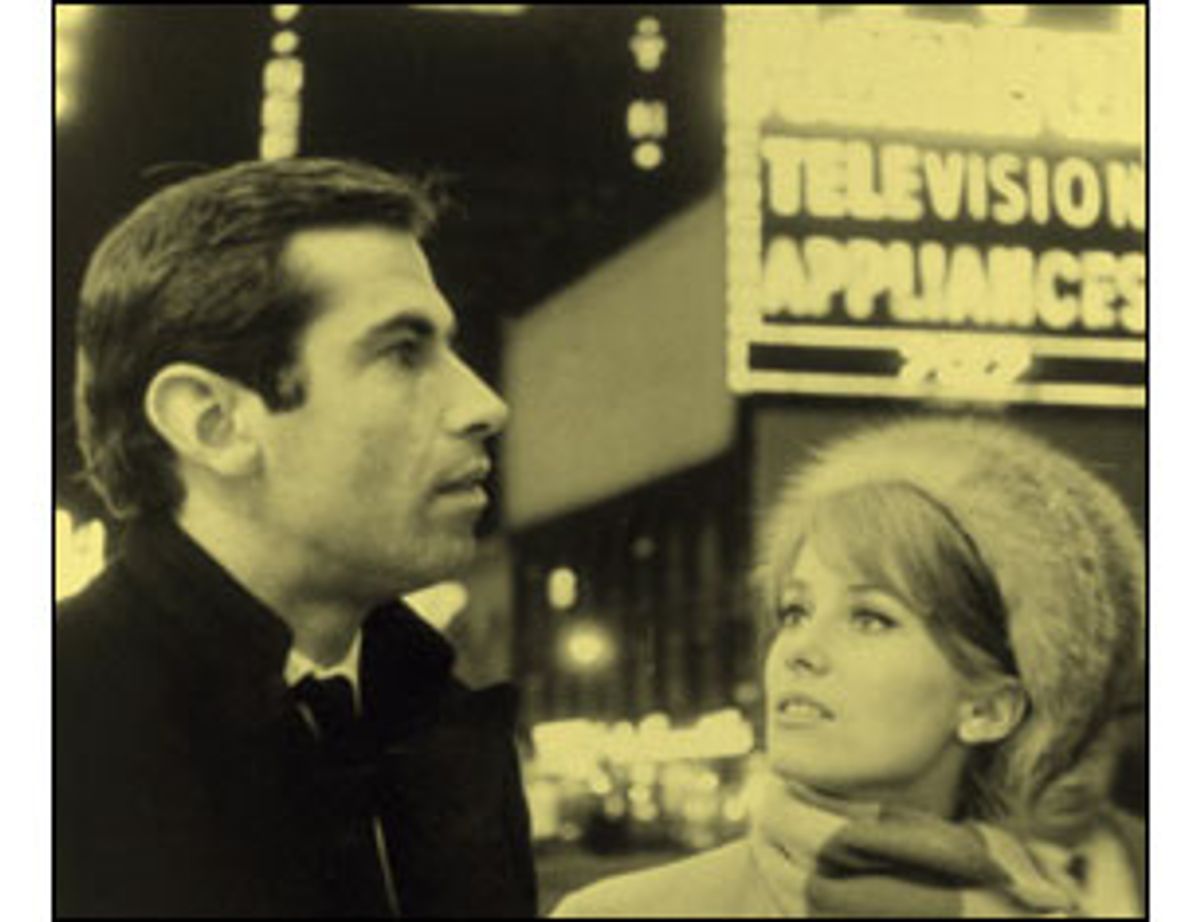

If "And God ... " is as close as Vadim came to a credo, a guiltless celebration of the pleasures of sex, love, food, sea and sun, it makes sense that his best film revolves around what for him seems the only true sin: the poisoning of pleasure. "Les liaisons dangereuses" (1959; rereleased here about 10 years ago as "Dangerous Liaisons 1960"), a modern-day retelling of Choderlos De Laclos's epistolary novel, is the work of a hedonist moralist with a sting in his tail. The prologue Vadim filmed for the American release, a sly digression in which he assures us that not all married French women are like the calculating temptress Jeanne Moreau plays in the film, sets you up to expect a droll, winking sex farce. And then the movie knocks you flat.

The bourgeois world of late '50s France turns out to be a suitably decadent substitution for the luxuriousness of the 18th century. The regality has been stripped away, but what's left is the story's essence of acrid, bitter gamesmanship. As in Laclos, the world of Vadim's movie is a velvet trap, sealed off from the tedious necessities of everyday life. In this demimonde, where every affair can be counted on to become instant public knowledge, maintaining an appearance of coolly cynical disinterest takes precedence over any adherence to morality. The only protection not afforded its inhabitants is from the claws of their contemporaries. Infidelity makes for good gossip, but nothing as juicy as a fall from privilege.

The lovers who plot to destroy innocents are married here. Valmont (Gerard Philipe in one of his last films; he died shortly afterward at 36) is angling for an ambassadorship, and the charm of his wife, Juliette (Moreau), has brought him near it. The story depends on our being seduced by their amorality (Juliette refuses to sleep with Valmont, explaining she is never unfaithful to her lovers) only to be gradually bothered and finally appalled by the human wreckage they wreak. Expertly scored to the music of Thelonious Monk and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, the movie turns Vadim's postcard lyricism (lovers frolicking in the surf) into genuine romantic poignance as Valmont goes beyond the boundaries of his game by falling in love with his conquest Marianne (Stroyberg, presented by her then-husband with a touching vulnerability that makes up her for uneven acting). It's a supremely sophisticated film about the limits of sophistication. As the competition between Valmont and Juliette becomes more and more deadly, we're less and less able to be amused, and more and more, like Valmont, prodded into feeling. And feeling that is awakened out of callousness can be devastating. There are shots that seem to define the characters. Juliette swathed in an ocelot coat walking like a grimly determined hunter through a symmetrical landscape of bare trees; Valmont seen through the slats of a rocking chair that contain him like the bars of a prison cell. Moreau, who becomes more radiant as she becomes more devious, and Philipe, who has the poignancy of a grown man discovering the pang of love, are superb.

"Les liaisons dangereuses" suggests the director that Vadim could have been. But it seems churlish to slight the director he was since the pleasures of his films seem to spring from a pleasure in life itself, and who can blame anyone for choosing life over art? When Moreau's Juliette is disgusted by Valmont's falling in love with Marianne she tells him, "My Valmont was charming. Mme. Tourvel gives me a husband." People magazine reported last week that Bardot, remembering the man who made her a star, called Vadim "seduction itself." Of the men she married after him, she said, "They were only husbands."

Shares