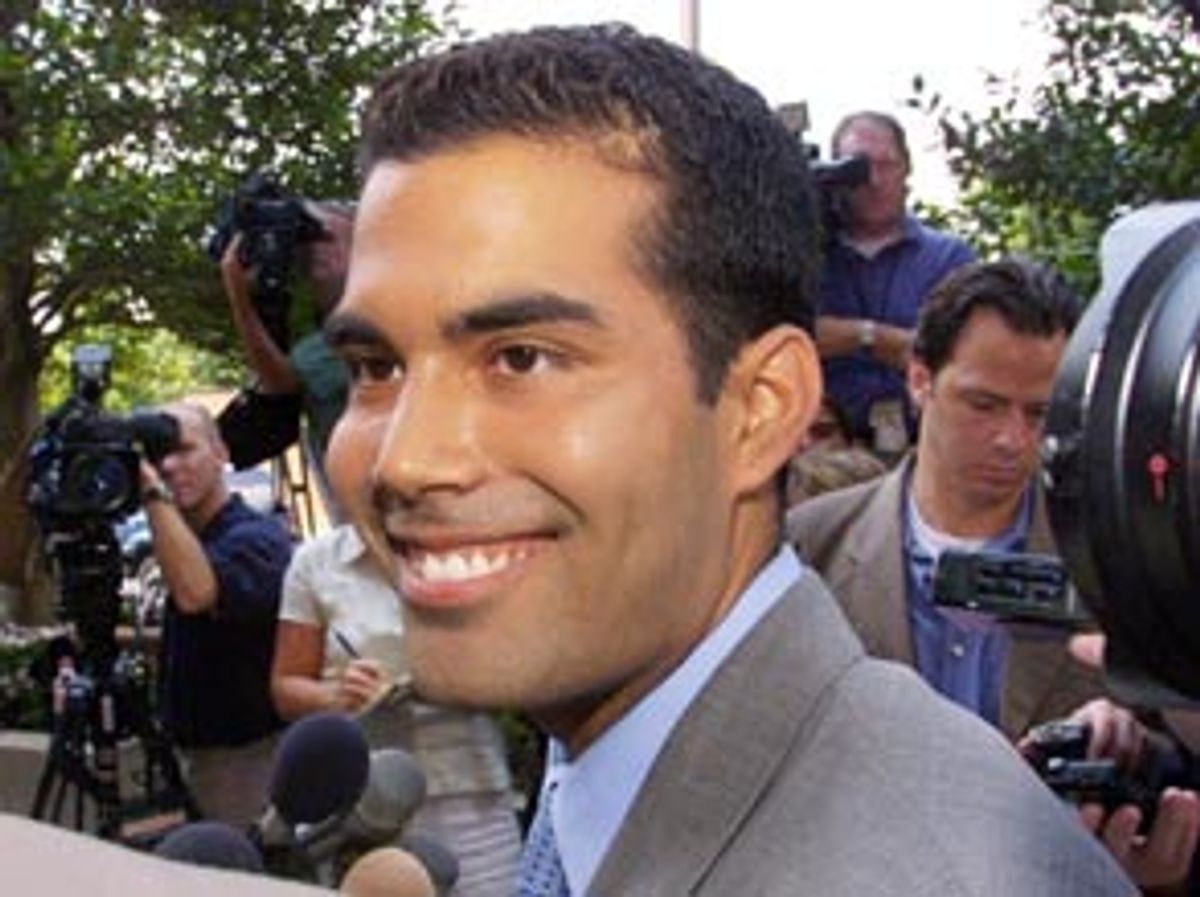

When George P. Bush -- or just "P.," as his family calls him -- showed up at an Arlington, Va., barbecue joint this week to talk with members of a local chapter of the Young Hispanic Republican Association -- many wearing pins that read: "Viva Bush!" -- he was met by a team of eight TV cameras.

"That's more than Steve Forbes got at any major event," cracked one reporter.

P. has one obvious factor in his favor that Forbes never will: He's eye candy. Salsa-sexy, lean and disconcertingly smooth is P. And what he's offering this day, complementing the pulled pork, is a diet of nice, soothing rhetoric.

The media lobs a few softballs. "George, can you tell us what your message is for young Hispanics?" is one. He handles it like a pro: He fills the air with words, throws in a statistic and avoids really saying much.

"I think that our generation definitely has a label of being apathetic, but I think a lot of younger people would disagree with that," he says. "One statistic that I found very interesting is that young Americans, more so than before, are devoting time to their communities, volunteering their time. I think it goes to show that our generation is socially conscious, but I think campaigns -- especially my uncle's campaign -- is trying to reach out more and channel that enthusiasm, channel that energy, so that they do register, they do vote, get involved."

P. is the son of Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and Columba, the nephew of George W. Bush and grandson of former President George Bush, who once famously referred to him and his two siblings, while pointing out his grandchildren to Ronald and Nancy Reagan, as "the little brown ones." That P.'s a Spanish-speaking Latino (his mother was born in Mexico) adds to his value for his uncle's campaign.

Even more valuable is his performance: P.'s a natural on the stump, and will reach his first national audience during the GOP's national convention, beginning July 31. Generally, the media greets him with a pool of drool. P. even hit No. 4 on People magazine's list of the "Top 100 Eligible Bachelors."

As his profile has increased, there's still a lot about P. nobody knows much about, aside from the standard political aphorisms he so pleasantly spouts. But a group of his close college friends from Rice University, where P. graduated in 1998, describe a mellow, charming guy savvy enough to tell when people were sidling up to him because of his famous last name. A guy who introduced himself as "George," and never as "George Bush."

They also describe someone who is definitely an independent thinker, and much less conservative than the uncle he's campaigning for.

But even though P. will serve as youth chairman of the GOP convention, his friend Chris Fide says that in recent e-mails, P. still insists he's not sure that politics is for him. "He keeps stating, 'I'm not sure I want to go into politics,'" Fide says. "Meanwhile, he just told me that he's 'taken off on a three-week barnstorming tour where I'm going to try to make a speech, defend it, then make a difference, which is what I love doing.' Then three sentences later he's saying that he's not going to run for anything ever. The two ideas are butting against each other."

So far, P. isn't subjecting his newfound celebrity to much introspection and analysis. He's still "in the honeymoon period," Fide says. "The things he's saying are, one way or another, making it into print. And he's just happy that his name's out there" and that he's helping his uncle's candidacy.

"It's pretty crazy" to see him on TV, says another friend, Mike Donovan. "He always said he didn't want to get into the political racket, but he seems to be heading that way whether he wants to or not."

P. has quickly become an expert at the benign comments you can also hear from the other side, from the mouth of Vice President Al Gore's oldest daughter, Karenna Gore Schiff, 26, who, like P., is the Generation X spokesmodel sent out by her family's campaign to put on a young, fresh face for the cameras. P. appeals to Latino voters and helps de-emphasize the Bob Jones-y side of his uncle; Karenna makes like the prototypical professional woman/soccer-mom-in-training and assists in warming up her pop's blood temperature to above freezing.

Having been raised in the public eye -- Karenna turned 3 on the day her father won the Democratic primary in his first run for Congress, P.'s earliest memory is of his grandfather declaring his intention to run for president in 1979 -- both are as polished as the good silver. At events and rallies they shake every hand, make eye contact, smile blindingly, greet every question and comment -- no matter how inane or sycophantic -- with what looks remarkably like interest. Comparatively free of baggage and enemies, they are in some ways more appealing candidates than their respective relatives seeking the presidency.

Politicians since the dawn of time have used their children for such ends, but here the youngsters are being trotted out under the guise of substance. Because, in addition to the uncontroversial subjects of increasing voter turnout and derailing Gen X apathy, P. and Karenna do address issues of some debate: Young mom Karenna talks about the urgent need to keep the Supreme Court abortion-friendly, while P. professes his pride in his Latino heritage and serves as a new face for the GOP.

Karenna's influence is much greater than P.'s; she is one of her father's most trusted advisors, though not every suggestion she's made -- such as bringing in feminist author Naomi Wolf -- has been heralded as wise. Though she urged her father to move his campaign from D.C. to Nashville, she also encouraged him to give his "no controlling legal authority" press conference before he knew all the facts and was ready for the tough questions.

But it's not tough to see them as a logical result of the characters of the campaigns from whence they came, outgrowths of Al Gore's earnestness and George W. Bush's emphasis on symbols and image. Bush-whackers find it easy to see P. as the Darva Conger of the 2000 election, with little to recommend him but good looks and one key familial connection.

The campaign has done its part to feed this perception: In a gushing New York Times profile, one unnamed Bush aide compared P. to "Ricky Martin, except better looking." Another added that P. is "very smooth. Rico suave. Chicks ate him up -- they did." And Uncle George himself has said about P., "He's a handsome dude, isn't he?"

P., meanwhile, has said that he wants to be known for more than his looks.

But back at Rice, he didn't want to be known really at all. There "he liked to keep a low profile," his friend Kent Voss says. "He knew there were girls who wanted to go out with him because he was 'George Bush' and not because of who he was.

"He'd be like, 'She just likes me because of my name,'" Voss says. "So he liked to sniff out people who wanted to be friends with him because he was 'George Bush' vs. the fact that he was a good guy who liked to play intramural sports and was a good guy to hang out with."

Because of his celebrity on the small campus, P.'s freshman year was somewhat tumultuous. According to Bryce Allen, his college roommate for three years, Rice's small size -- there are about 2,700 students in the undergraduate program -- word got around quickly that President Bush's grandson was there. "For the first couple [of] weeks at least, people did come to see the Bush; rather than trying to find out who the new freshman was, they came to stare," Allen says. "I think after a couple of weeks of that, he got tired of that kind of attention and he just wanted to blend in."

Some on campus didn't like his attitude. "He was cautious," Fide says. "It might have come off as arrogance to some people who didn't know him, or who he didn't allow to get to know him." They used to tease him, Voss says, "for not using his name more. We used to say, 'George, you could get any girl you wanted to!'"

Now he gets to pick and choose media outlets. Or, rather, his uncle's campaign does the picking for him. Though P. told a Salon reporter that he would gladly sit for an interview, his uncle's campaign had other ideas.

But maybe they knew what they were doing; Bush seems to be already realizing that no one will wait for him to start talking about issues before attacking him on them.

For instance, according to his friends, P. was bummed when the Houston Press, a Texas alternative weekly, published a hard-hitting story at the end of June claiming that P. wasn't active in Latino politics while a student at Rice.

"National coverage would seem to indicate that George P. is the essence of passion for his people ... with a la vida loca commitment and an obvious legacy of activism for Latino causes," according to the Press story. "Just don't ask his former classmates at Rice University about that." The story quoted past presidents of the Hispanic Association for Cultural Enrichment at Rice (HACER), both of whom said P. was AWOL on campus Latino issues and events.

Mike Gomez, a past president of HACER, tells Salon that "for the most part we were pretty cognizant of who was involved and who wasn't. It's a small university, only about 2,700 students, like a high school."

"I don't make any character judgment on that," Gomez says. "But in regards to HACER or minority issues or any of those areas dealing with Hispanics, I wasn't aware that he was involved at all. Nor did I hear anyone talk about him."

"It's not so much an issue about ethnicity or cultural pride, things that I believe are wholly personal, but an issue of whether or not George P. really cares about the Latino community as a whole," Gomez goes on. "If he is going to push his uncle for president under the auspices of being Hispanic, I think it is legitimate to question his credibility, when he has not demonstrated in the past that the these issues are important to him."

But P.'s buddies defend their friend. His friend Kent Voss says P.'s insistence on having a low profile was "one of the reasons for him not being active in groups like HACER." His involvement would have been hyped, Voss hypothesizes, which he wouldn't have wanted. "It's true that he wasn't involved in HACER," acknowledges another friend, Marty Makulski, "but I have a lot of friends who are Hispanic who weren't involved in HACER. It just wasn't his thing at the time."

Donovan adds that any implication that P. "didn't embrace his Hispanic heritage 'til recently" is "completely untrue." P. had "a lot of close friends who "were Hispanic, and it seemed to me that he always embraced that side of himself."

But when P. was asked about his participation with HACER at a recent Seattle event, he insisted that he had attended some events, adding, "I think the president of HACER has a case of amnesia." What we are possibly witnessing is the birth of a politician. It is not always a pretty sight, as pretty as the politician might be.

Part of that may be because P.'s involvement in his uncle's campaign, all of his friends agree, stems more from the Bush family ethos of loyalty than from any of his own political views.

And on the trail, he does little but -- with a self-deprecating flourish -- repeat what his uncle says, never straying from message. He says what boils down to this: His uncle supports education. He passed two large tax cuts that, replicated on a national level, will help other Latinos realize the American dream. His uncle is reaching out to Latinos; it's "a real sincere effort," he says.

When asked about his political views, P. generally demurs. But he's coming around to the idea of embracing the family business. "He wants his uncle to be elected," says Allen. "But also he's interested now in getting his feet wet politically."

And W., who fiercely guards his 18-year-old twin daughters from the press, has been more than willing to grab P. and use him for every purpose imaginable -- and quite shrewdly. At an April campaign appearance in California, where Bush was heralded for "distancing" himself from Gov. Pete Wilson's immigration policies, P. was bolder than his uncle would ever hope to be.

Bush told the National Hispanic Women's Conference at the Regal Biltmore Hotel that he wants "the American dream, el sueqo Americano, to belong to all Americans; if your parents are first-generation ... this dream belongs to you as much as anybody else."

Bush didn't mention Wilson's name. P., on the other hand, told reporters -- in a moment of candor you won't likely hear from him again -- that "our biggest challenge will be to separate my uncle from the rest of the Republican Party."

"There is a perception in the Latino community," he said. "When the word 'Republican' is brought up, the image of Pete Wilson is restored in the minds of many voters."

While most of P.'s friends insist that the budding pol's moderate views on immigration are legit, Donovan says that he thinks P. is "a lot more open-minded" than his uncle.

"I don't know if that's more a function of his youth or what," Donovan says, but during late-night bull sessions in the dorm, P. was always interested in different perspectives on issues.

Voss doesn't think P. is anywhere near as conservative as the campaign for which he stumps. "I wouldn't say he was a Pat Buchanan, let's put it that way. I don't thing he's as strong-viewed as the party would like to portray," Voss says. "He's more moderate than the other George, the George from Texas."

While close with the family's political views on economic and fiscal issues, his friends say, P. is, according to Fide, "much more liberal on social issues than his uncle, and more so that his grandfather."

Specifically, these friends say that P. is more liberal on immigration and on gun control. They put the other two George Bushes on different poles: George W. supports the National Rifle Association's position on each and every gun issue, while the former President Bush resigned from the NRA after it made references in its direct mail to "jack-booted government thugs."

Fide says P. would "side with his grandfather more than his uncle on gun control."

P.'s involvement in an inner-city Houston tutoring program while at Rice and a post-graduation year teaching at an inner-city school in Florida have only reinforced this position.

Fide says: "Where he taught and some of the things he saw, plus all of the things happening all over the country with kids and guns, I think that position has been strengthened in the last few years."

Asked if P. -- during some future hypothetical run for office -- would run as a Republican, all say of course. "It would cause a lot of trouble if, as a member of the Bush family, you didn't, I guess," Voss says.

Now, Allen says that P. is "still a little leery of the publicity he's getting because of his name, but at the same time I think he's coming to realize that he is part of this political family and while he can have his own views he's -- like it or not -- part of the family. He's coming to terms with that and he's starting to like it more. I think that that's what the real change is for him"

Back at Rice, "he wanted to exert his independence, and I don't think he thought he could do that and still be a Bush. And I think he's found out that he can."

Makulski says that P. "appreciates all the positive stuff" about him in the media, though some of it, like the People spread, is "a little dizzying."

He's less enthusiastic about articles like the Houston Press story, which Makulski says "made him look opportunistic, things like that he finds really frustrating and aggravating." But then, P.'s not exactly a babe in the woods: "He's seen how the press has handled his grandfather, his father and his uncle, as well as some of the negative reports about his mother."

According to Makulski, however, the goodness and the commitment P. projects in his interviews is genuine. At Rice, the two participated in "Houston One-On-One," a mentoring and tutoring program for at-risk Hispanic youth sponsored by the Catholic Church. Each Saturday for two years, they'd spent an hour tutoring the kids "and then an hour playing games with them, and talking to them about morals and values," Makulski says.

Other than that, it was all pretty normal. Their gang of roughly a dozen guys would go to the campus' undergraduate bar, Willy's Pub, on Thursday nights. They'd attend Rice football and basketball games, watch sports on the dorm's big-screen TV, play dorm sports. He was a freshman walk-on on the baseball team, but he didn't get much playing time and so eventually quit. He was a fair student, but he buckled down a bit during his last two years and even made the dean's list his last two semesters. All fairly standard.

"Once people stopped treating him like someone to come and stare at, I think he was a real fun guy," says Allen, laughing. When asked what he's laughing about, Allen says, "I was just thinking about some of the George stories," but he won't share any. "Not all of them are fit for print, certainly. He's a great guy and a very loyal guy and I think anything I might say would get him in trouble -- so I think I should just keep my mouth shut."

As for girls, well, Makulski says that P.'s "not the Casanova he's being made out to be." Freshman year, Donovan says, P. was "a little bit wild," but then "once he got a girlfriend [during his sophomore year] he kind of settled down." The couple went through the normal ups and downs, and broke up only recently.

"He was just one of the guys, struggling on a budget, living off Domino's," Makulski says.

There was the one time -- Halloween of 1994, their freshman year -- when P. took the boys over to his grandparents' new house to trick or treat. It was George H.W. and Barbara Bush's first time back in Houston for almost a dozen years. But even that, Makulski says, was just P. making an effort "to get his Gramps to know his friends."

Some of the guys dressed in drag; President Bush "had no problem with it," says Fide, "but his grandmother was a little taken aback. She looked at us like, 'So! This is what they do up at Rice!'"

P. would often spend Sundays having brunch with his grandparents, at a local Mexican restaurant called Molina's. His friends would often get a laugh when the former president would leave messages on P.'s answering machine: "P., it's Gampie," sounding quite like Dana Carvey's famous imitation. Eventually, "Gampie" wanted to meet them all, so P. began bringing some to brunch at Molina's; it became a routine.

"He's very, very charming," says Voss. "It's been quite interesting to see him work his magic" on the rest of the country. "We give him a lot of shit for being on the cover of the [New York] Times and being named one of the most eligible bachelors. I think he likes some of the attention, but I don't think it goes to his head."

It'd be hard for it not to. Few in the world of politics are afforded such unquestioning adulation. The media giveth and the media taketh away, but right now for P. it's just giveth giveth giveth. ("Isn't it true that a lot of young, Latino Democrats are starting to look at the Republican Party and someone like you, who brings a lot of important emphasis, can get them more involved?" one questioner asked at the Arlington event, verbatim.)

He's gotten a pass on the rougher questions he could eventually face. No one asks him about South Texas's colonias, the poorest region in the nation, where an estimated 400,000 Hispanics live in third-world conditions. Nor does anyone mention last year's charge by Enrique "Rick" Dovalina, president of the League of United Latin American Citizens -- the nation's oldest Latino civil rights organization. Dovalina, who has been critical of Gov. Bush's position on a number of issues, said that "we're very disappointed with the way [Gov. Bush is] parading around with his taco politics," posing for the cameras in Mexican restaurants without really addressing issues of importance to the Latino community.

And it looks like he'll disappear before the questions can really heat up. "I really play a minor role," P. says. "Personally, I'm going to end -- unfortunately -- my involvement with the campaign after the convention because I'm hoping to start a legal career. So we'll see how it turns out."

Having been rejected by the law schools at Columbia, Harvard, New York University and Yale, P. will begin studies at the University of Texas law school in the fall, and for the time being, he says, his political life will end. His normal life can may even go back to being, well, almost normal. The guys saw P. just a few months ago, in April, when Fide got married and P. served as a groomsman. The bride's teenage sisters were aflutter at the sight of the superstar. Fide laughed when he later heard P. had asked for his 21-year-old stepsister's phone number. "Same old George of six or seven years ago," Fide says he thought at the time.

"He was the same old George, except now most people in the world knew who he was," Voss says. "He was the same guy we all knew back then. Though he was probably dressed a little nicer."

Shares