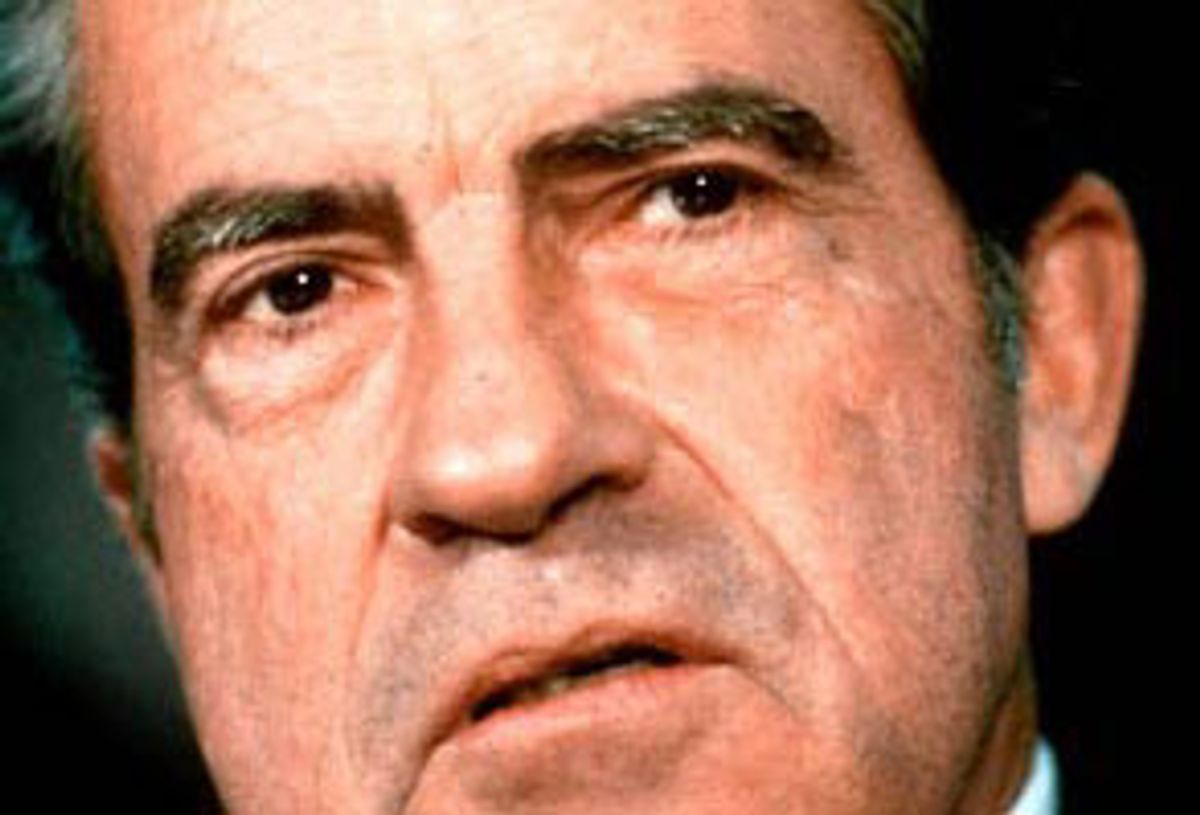

Anthony Summers' new Richard Nixon biography "Arrogance of Power" is by no means the first, and certainly won't be the last, to serve up a decidedly unflattering portrait of the 37th president of the United States. Over the course of almost 500 pages, Summers recounts numerous episodes from Nixon's political life -- many familiar, others not. Yet, as is so often the case with hotly hyped works of popular history, attention has focused on three extremely controversial charges to the exclusion of most of the rest of what is contained in the book.

Of course, through no one's fault but his own, rumors and less than fully substantiated reports about Nixon's misdeeds are treated with much less skepticism than those of other occupants of the White House. Just think. Ever hear the one about how Nixon used the IRS to punish his enemies? Or maybe about how Nixon had a crew of goons break into a State Department whistleblower's psychiatrist's office? Or even the one about how Nixon sent a crew of burglars to break into DNC headquarters to spy on the Democrats? Well, you get the idea.

Summers' two most sensational charges are that Nixon beat his wife on at least one occasion in 1962 and during the last years of his presidency took the drug Dilantin (a drug used for a variety of ailments including seizures but subsequently discredited for psychiatric use), which he had not been prescribed by a doctor. But what of the charges? And how will they affect our collective understanding of Nixon and his presidency, if at all? A host of Nixon observers, historians, close friends and other committed critics expressed extreme skepticism about the charges of wife beating and drug abuse. Irwin Gellman, an historian who is writing a generally sympathetic, three-volume biography of Nixon told Salon that "people were giving him stuff all the time. But Jack Dreyfuss [the founder of the Dreyfuss Fund and near-missionary promoter of Dilantin, who now says he provided Nixon with the drug] was a big-time Republican contributor. Nixon wasn't going to embarrass himself by saying he's a flake. I assume he either threw them away or gave them to one of his staff."

Historian Stanley Kutler, who's written his own books on Nixon, finds the charges of wife-beating equally difficult to accept. Summers' evidence for this charge comes from John Sears, a former Nixon aide, who told Summers that Waller Taylor, a Nixon family lawyer, told him that Nixon had punched his wife in the aftermath of his 1962 defeat for the California governor's race. In other words, it's not exactly a firsthand account. "In any seminar in critical methodology, you learn you need evidence. This just doesn't even come close. If you read Haldeman's diaries and the conversations between him and Nixon, the evidence of emotional abuse [of Nixon's wife] is fairly well-documented. But I've never seen any evidence of wife beating."

Leonard Garment, Nixon's friend and former counsel, while not commenting on the specific charges, expressed a similarly low opinion of the book. "Look, politics is a porous profession. But I see stuff like this, this book, as just an example of the congealed hatred which still exists for this man."

The essence of the matter is that Summers' charges are quite serious. The evidence Summers adduces to support them is not insignificant. But it also falls far short of proving his charges. Not only does his evidence not stand the scrutiny scholars would demand. It also falls well short of the looser strictures we properly apply to popular historical writing. The fact that these charges got included and are receiving so much attention is not only unfortunate for Nixon's reputation, but also for Summers' book. Because the book contains at least some information that appears to add important details to the story of the Nixon presidency, details which are sure to be lost in the frenzy over the wife-beating and drug abuse charges. The most provocative of these is Summers' contention that Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, concerned about Nixon's deteriorating mental state, ordered the armed forces not to react to orders from the White House without first clearing them with the secretaries of State and Defense. Summers quotes Schlesinger at length and Schlesinger last week told the New York Times that "the book's description of events was the most complete and most accurate account of [my] actions."

Unlike the other claims receiving attention in the book, this is an on-the-record account by one of the principals in question. And even those most dismissive of Summers' other claims don't rule out the essence of what Summers says in this section. "Of all the claims," says Gellman, "this is the one which is closest to reality. Look, Schlesinger has an ego, like Nixon had an ego, like Kissinger has an ego. You figure Schlesinger was hearing all kinds of things how Nixon was losing it. He figures he's not going to be in a position where Nixon goes 'Dr. Strangelove.' So he says unless [orders for military action] goes through the chain, through the guys over at the Pentagon, I'm not going to allow it. Other than the nature of how Summers presents it, I don't know that I disagree with that."

To Gellman, the fact that Schlesinger may have over-reacted to what he was hearing about Nixon's mental stability isn't necessarily so surprising. And just because Schlesinger thought Nixon was losing it doesn't mean that he was. That's true as far as that goes, of course. But the fact that the Secretary of Defense took it upon himself to take precautions against the president's using the armed services for ill purposes is, needless to say, quite a significant story in itself. And for this alone Summers' book adds significantly to our understanding of the Nixon presidency in its final days.

Gellman, for his part, sees Summers' work as yet another example of the "sad state of historical research."

"It's going to be put in with Edmund Morris's book ["Dutch" on Ronald Reagan]. To writers like them, what's more important is the sensational salacious stuff ... Viking [the book's publisher] should be ashamed."

But Summers also has his defenders. Seymour Hersh, one of the most acclaimed of all investigative journalists and no stranger to controversy himself, cautioned critics who would dismiss Summers out of hand. "I haven't read the book yet," Hersh told Salon, "but I have reason to think there's a lot of good, carefully reported stuff in his book. Tony's a cutting-edge guy and he's nobody's fool. A lot of people are very eager to trash him, but Tony Summers works his butt off. I don't always agree with him, and it's easy to dismiss him, but his critics do so at their own peril."

Shares