I've heard tango described as a three-minute love affair with someone you do not know. But I believe a concern for time is the enemy of love.

I met Ofelia while I was eating ice cream outside the famous Berthillon ice cream store on the Ile Saint-Louis in Paris. It was rum ice cream, with rather swollen golden raisins. I was headed for the Quai Saint-Bernard, where you can dance the tango beneath the trees on Saturday afternoons during the summer.

Ofelia was coming out of the store herself, a lush mound of blueberry capping a slim cone in one hand, and a copy of the Buenos Aires daily El Clarín in the other. She was in her early 40s, dressed in blue, a short velvet summer dress that exposed her shoulders. Her black hair was also quite short, combed back severely and gleaming -- "pelo engominado" in the Spanish phrase. Our eyes met, but she looked away. I could tell by the interested second glance she gave me over her shoulder that she had noticed me.

She passed up the street toward the Pont de Sully, and I followed her. She crossed the bridge and entered the small triangular park at the end of the island. It was a warm day of summer clarity, the high trees in the park languid in their movement back and forth in the breeze from the river. She sat down on a bench and surveyed the newspaper before her. I sat on a bench several feet away.

In tango there is something called the "cabeceo" -- a gesture by which you invite someone to dance. It can be a raising of an eyebrow when you've caught a person's eye, a nod of the head, something silent but very well understood. If the "cabeceo" is successful, you stand and meet the other person on the dance floor, you exchange pleasantries for a moment or two. Then, at an appropriate moment, you enter each other's arms and dance.

I could not get Ofelia's attention. She appeared distracted, the fingers of her left hand drumming her knee as she looked toward the entry gate to the park. She appeared to be waiting for someone.

Suddenly she glanced toward me.

I felt I should look away. But I wanted to meet her. I stood and approached her.

"Pardon me," I said.

Her fingernails were painted like splashes of blood.

"May I ... ?"

I realize now that even these first words in that park were of love and the senses, because her mouth opened in a smile as we spoke. Because I had been watching Ofelia's eyes, it was easy to begin a contemplation of her lips, lips that I already loved.

"Of course, please sit down," she said.

She rested her hands together on her folded newspaper.

"My name is Luis," I muttered.

There was a flutter of intimacy as she looked at me. My words were unimportant. I gestured toward her paper.

"Are you by any chance going to dance tango?"

Ofelia's mouth moved softly, the lipstick she wore bright and dark, wet-appearing and elastic. As the words appeared, charged with feeling, her mouth became so as well.

"I'm Ofelia," she replied. "Yes, I am dancing the tango."

The walkway on the Quai Saint-Bernard gives a view of the Seine that includes Notre Dame and the Opera House of the Bastille. It is near the old Gare d'Austerlitz and its Victorian resonance, a memorial built during stodgy times that were soon to be washed away by things like World War I and tango.

We'd been dancing for about an hour. The sun glistened in the sweat that had appeared in the temples beneath her hair. She'd just put her glass of wine down on the stone ledge where we were sitting. Her blue dress (perhaps even the same shade of blue as the dress Ingrid Bergman wore in "Casabanca," in love with Bogart, the Germans wearing gray) and her black pumps, without stockings, had flashed through our many "molinete" turns.

They were playing "Anclao en París," a tango of Carlos Gardel I love dancing to, though I seldom have the chance to do so. Argentines do not dance to Gardel's music, out of respect for his memory. He enjoys a kind of saintly grandeur in the Argentine pantheon, the greatest tango singer of all time, the very essence of tango and therefore of the history of that country. It is a long-held tradition in Argentina that to dance to Gardel's music is an offense to his soul. As an Argentine I respect that, but it is an opportunity missed because Gardel's voice is so elastic, expressive and contemporary, imbued with so much jazz musicality and feeling that it's a shame not to dance to it. Tirao por la vida de errante bohemio, estoy, Buenos Aires, anclao en París; curtido de males, bandeado de apremios, te evoco desde este lejano país. (Taken up by the rambling bohemian life, I am, Buenos Aires, stuck here in Paris; harmed and hardened, pushed around, I conjure you up from this faraway country.)

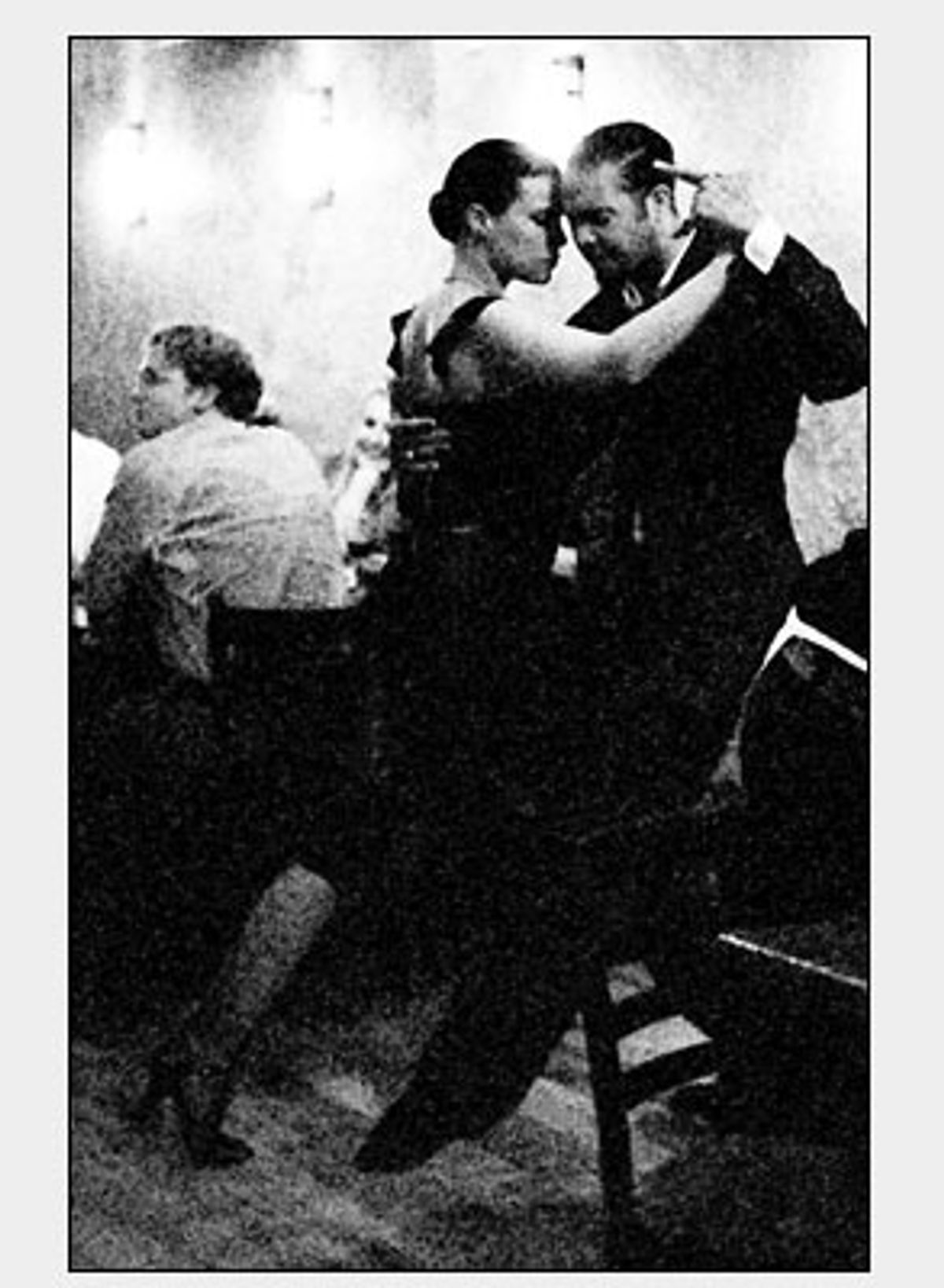

We decided to dance despite our respect for tradition, holding our entwined hands by the side of my pocket, cheek to cheek in a fast step. Once or twice, we allowed our hands to part, and I danced with my left hand in my pocket, arrogant in the Parisian afternoon. Gardel mourned our lost Buenos Aires. I caressed Ofelia's cheek with my lips and we turned, turned again, our legs conversing sometimes like a couple in love, sometimes arguing.

Ofelia told me a few hours later that she had fallen in love with me so completely in those moments by the river that she could barely let me go. I knew that couldn't be so. We barely knew each other. But I also knew that Ofelia reflected the light in the damp heat of her dancing. I had been dazzled by her. The curving walkway, the roughly cut stone tiles on which we were dancing, the darkening trees, the ancient blue-green river -- all of it made me hope that Toulouse-Lautrec would stroll by on his way to Le Chat Noir (hopefully in the company of Gardel himself), fascinated by the sad bohemians seemingly in love, dancing there on the quay beneath the trees.

I asked her to come with me to my apartment.

"Oh, yes," she said. "Yes, I will."

The lace curtains were pushed aside now and then by fresh warm air coming in from the Place des Vosges. Light made its way through the folds in the sheets, the white shadowed gullies. Our clothing was strewn about, and the bedroom had an air of disheveled friendliness and pleasure.

Afterward -- after lying around talking, the air drying the sweat on us -- Ofelia slipped her dress back over her head and lowered it down her body. I caressed the dark blue cloth that now rounded her hips again, the velvet's softness an underscore of the curve of her hips and their soft resistance.

The clothing excited me because of what it covered. The declaration of Ofelia's body when she had been nude had thrilled me. There was strength and delicacy in the very smoothness of her skin. But I was just as moved when she was clothed because I now had a memory of her skin. I could remember, and imagine, what she had looked like without clothing.

I asked her to show me her breast once more, simply to let me see it. Her hand moved aside. The dress, still unsecured, slipped from one shoulder, and she allowed her breast to emerge. The cloth fell down to cover her belly. She was passive and looked away, enjoying her surrender. Her hair, soft black jade, moved against my lips as her breast came from beneath her hand and became its own beautiful curve once again, as before.

There was evidence of the warm air on her breast, the light blue vein that appeared in it seemingly swimming in a damp surface of perspiration, a reminder of the fact that it was still a summer afternoon and that there may not be a particular reason for her to be wearing clothes. Nonetheless, as I caressed the curve of her breast with my fingers and leaned over to kiss it, I covered her skin for a moment with the same cloth that she had just allowed to fall, and kissed her through the cloth, feeling the gathering of her breast against my lips, her nipple growing taut once more beneath the velvet, her hand resting on my cheek and her breath -- suddenly, again -- more hurried.

She left me an hour later. The sun had gone down, but the air was still quite warm. She would not give me her address in Buenos Aires, where she was returning the next day, mentioning to me finally, while holding my hand, that there was a husband, there were children.

I could not bear the fact that she was gone. I had wanted to see her again very badly, but she would not let me.

She had left her newspaper behind. I read an article about the fractious politics left in the wake of the presidency of Carlos Menem, how he had soured the state of mind of the Argentine people. I wasn't interested. I tossed the paper aside. It fell apart, falling in separate sheets to the rug. Leaning on the palm of my right hand, I looked out onto the quiet night street. At least Ofelia had left knowing how I felt about her. I whispered a lyric from a tango I knew, a famous tango. !María ...! En las sombras de mi pieza es tu paso el que regresa ... !María! Y es tu voz, pequeña y triste, la del día en que dijiste: "Ya no hay nada entre los dos ..." (María ...! In the shadows of my room/ It's your footstep that returns ... María! And it's your voice, small and sad,/ The same voice from the day you said, "There's nothing left between us ...")

Shares