The history books like to say that the men came home from Europe and the Pacific in 1945-46 brooding over the atom bomb, the lessons of the concentration camps and the "problem" of communism. But most men aren't like that. I've never seen any figures on the subject, but I'd bet that most men came home troubled by whether a girlfriend or a wife would still be there, waiting patiently; or whether they could suppress their new knowledge of foreign whores; or whether they could endure life without the buddy with whom they'd shared five campaigns and a bleak foxhole. We know divorce got a terrific boost from the war, but so did a larger realization of homosexual affection and need.

That's why "Gilda" (1946) is such a great American film, so exciting and disturbing still. Directed by Charles Vidor, written by Marion Parsonnet, produced and rewritten by Virginia Van Upp, it isn't guarded by big prestigious names. I'm not even quite sure that anyone working on it knew what it was about, or was organizing it toward its special ambiguity.

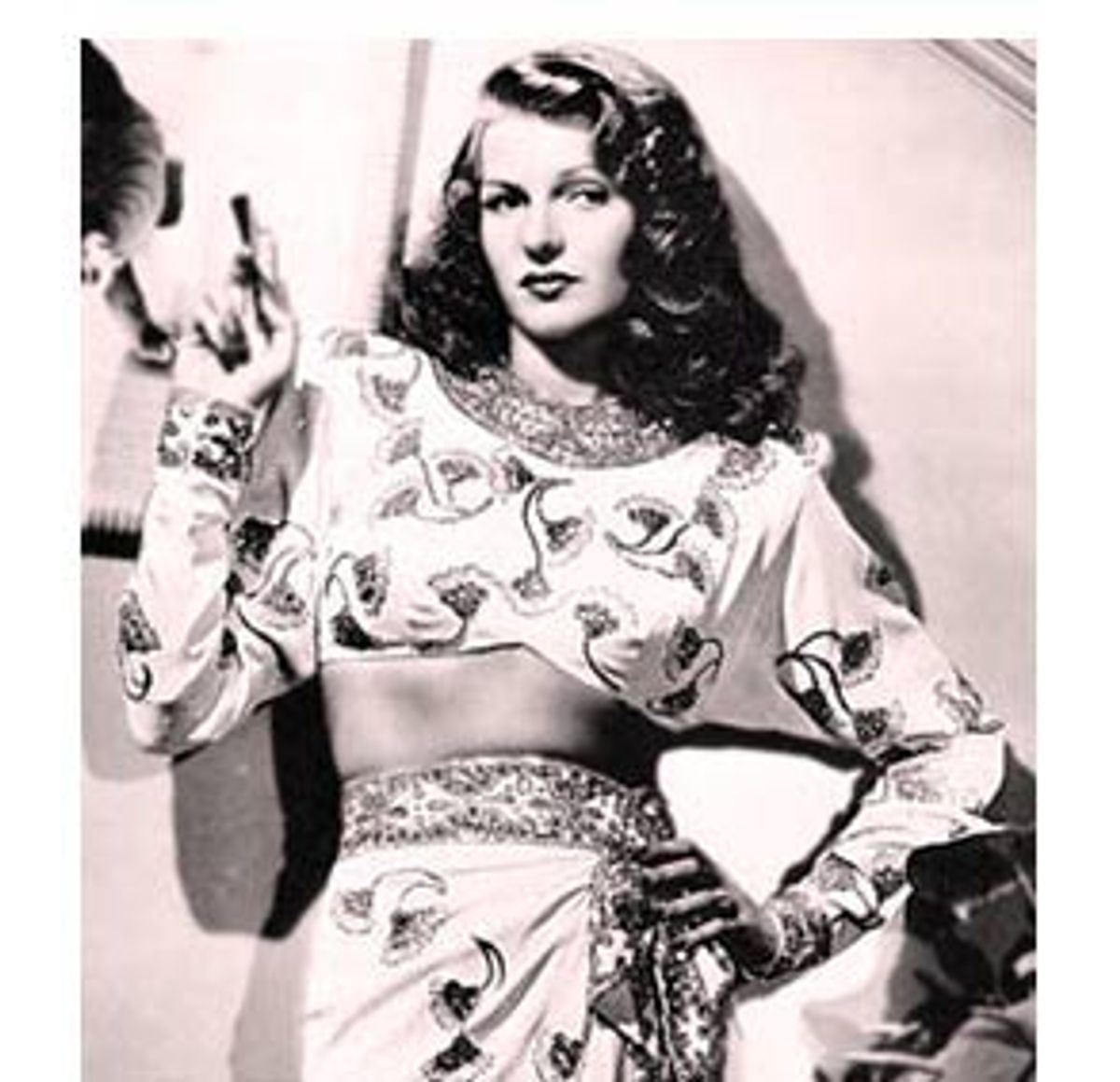

In some vague South American country, Ballin Mundson (George Macready) owns a casino. One night, on the waterfront, Mundson saves an American, Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford), from being beaten up. He hires Johnny to manage the casino and they become best buddies. It's a 1946 film: There's no hint of gay action between them, but the code is obvious now. Then Ballin goes away and comes back with a bride, Gilda (Rita Hayworth), who was once Johnny's girlfriend.

The atmosphere south of the border turns to poison: Like a lion-tamer with wicked kittens, Ballin watches Johnny and Gilda consumed by love and loathing. I stressed the rewriting earlier, because it seems that a lot of the uncommonly good dialogue was developed during shooting -- and as if out of some barely acknowledged understanding. For the film is based on a kind of mocking disgust with sex, and a true wish to destroy a betraying partner. I can think of no film before "Gilda" in which the three characters are such obvious candidates for the psychiatric couch. The only question is, who goes first?

Now, it's a movie still, and it gets a quick, whitewashed ending, as well as set-piece dance routines for Rita -- like "Put the Blame on Mame" (full of contempt for misogyny) -- that is so brilliantly photographed in black and white it could make a regiment come running; or come, running.

Rita was never so lovely, so flamboyant, or so close to ice cream with melting butterscotch sauce -- the sheer liquidity of the image is arousing, the waves of her hair, the ripples in a satin dress. Her image in the film became one of the classic pin-ups. But it's actually the talk, the backbiting, the savagery, that is most arresting, and it's a film that reveals a terrible fear of heterosexuality and a creeping urge toward same-sexism in a nation so trained by war service.

It's not that "Gilda" is an unknown quantity. But sometimes it gets misleadingly offered as a Hayworth vehicle or a film noir. It's both, yet Ford's cruel neurotic is really the best performance and the heart of the film. "Gilda" hasn't dated a quarter inch. In 1946 and '47, it was a box-office sensation, and its studio, Columbia, tried to repeat that. It missed every time -- probably because it never really knew just how dangerous a thing it had in its hands. It's an encouraging reminder of how grown-up a movie could be (50-plus years ago), if people had a lot on their minds.

Shares