Forget hoodoo: Attention to craftsmanship is its own kind of curse. Because Iain Softley's Southern gothic thriller "The Skeleton Key" is one of those late-summer releases that gets its turn only after all the big blockbusters have spent themselves -- and because the previews make it look kind of dumb -- moviegoers may just assume it's a piece of junk. Actually, it may not be junky enough: Softley, working from a script by Ehren Kruger ("The Ring Two"), puts so much care into layering moods and textures that he doesn't always scoot the action along as briskly as he should. There are sections of "The Skeleton Key" that feel poky and tasteful, as if throwing off too much energy would be an affront to good Southern manners. It's so genteel in mood and feeling that it doesn't fully spring to crazy life until too near the end.

Still, that's all part of Softley's plan. And what other picture this summer is going to give us creepy broken dolls, drawers and shelves full of yellowed bones and monkey skulls, and dusty jars filled with pickled pink-gray whatsits? And what other picture is going to give us flashes of Kate Hudson in her skivvies -- a kind of hoodoo in their own right? In "The Skeleton Key," earnest hospice worker Hudson takes a job at a vine-draped Louisiana estate to care for stroke victim John Hurt. Hurt's wife, polite but shifty-eyed Gena Rowlands, mistrusts Hudson from the start: As she keeps telling the family lawyer, Peter Sarsgaard, who's trying to help the old folks through these tough times, "She won't understand the house."

And who in their right mind would? This architectural ode to the old-time graciousness of the South is pretty enough from the outside, but inside, it's a warren of boarded-up doors just waiting for the right key, ominous rooms lit only by the meager shafts of light that manage to sneak through slatted windows, and crackled-cream doors and window frames that look as if they haven't seen the wet end of a paintbrush since 19-ought-two. (Cinematographer Daniel Mendel gives the movie a moody, moist look.) Disquieting religious statues nestled into various dark corners keep their glass eyes trained watchfully on the goings-on. Little wonder Hudson comes to believe that something isn't quite right with the place -- or with Rowlands, who has some very strict rules about when and how her bedridden, now-mute husband should get his "remedies."

Softley allows the tension to build slowly, using props as touchstones to help us find our way through the picture. (My favorite is a spooky, scratchy conjurers' recording from the '20s, which sounds like something from the 1981 Brian Eno/David Byrne collaboration "My Life in the Bush of Ghosts," only creepier.) This is just the kind of thriller you'd expect Softley to make -- if you ever know what to expect from Softley. His previous pictures include "The Wings of the Dove," a Henry James adaptation with a seductively soft look and a suprisingly sharp edge, and the Stu Sutcliffe biopic "Backbeat," which I consider his finest picture, as well as one of the greatest rock 'n' roll movies ever made. Softley is an intelligent, thoughtful director, and the travesty "K-Pax" is the proof. It's a picture that's hated, with very good reason, by almost everyone, but the typical Softley care and workmanship is there in every scene. There is such a thing as a noble failure, although I confess I wouldn't want to suffer through "K-Pax" again just to diagram the flow of its scenes or to relive its astonishing visual textures.

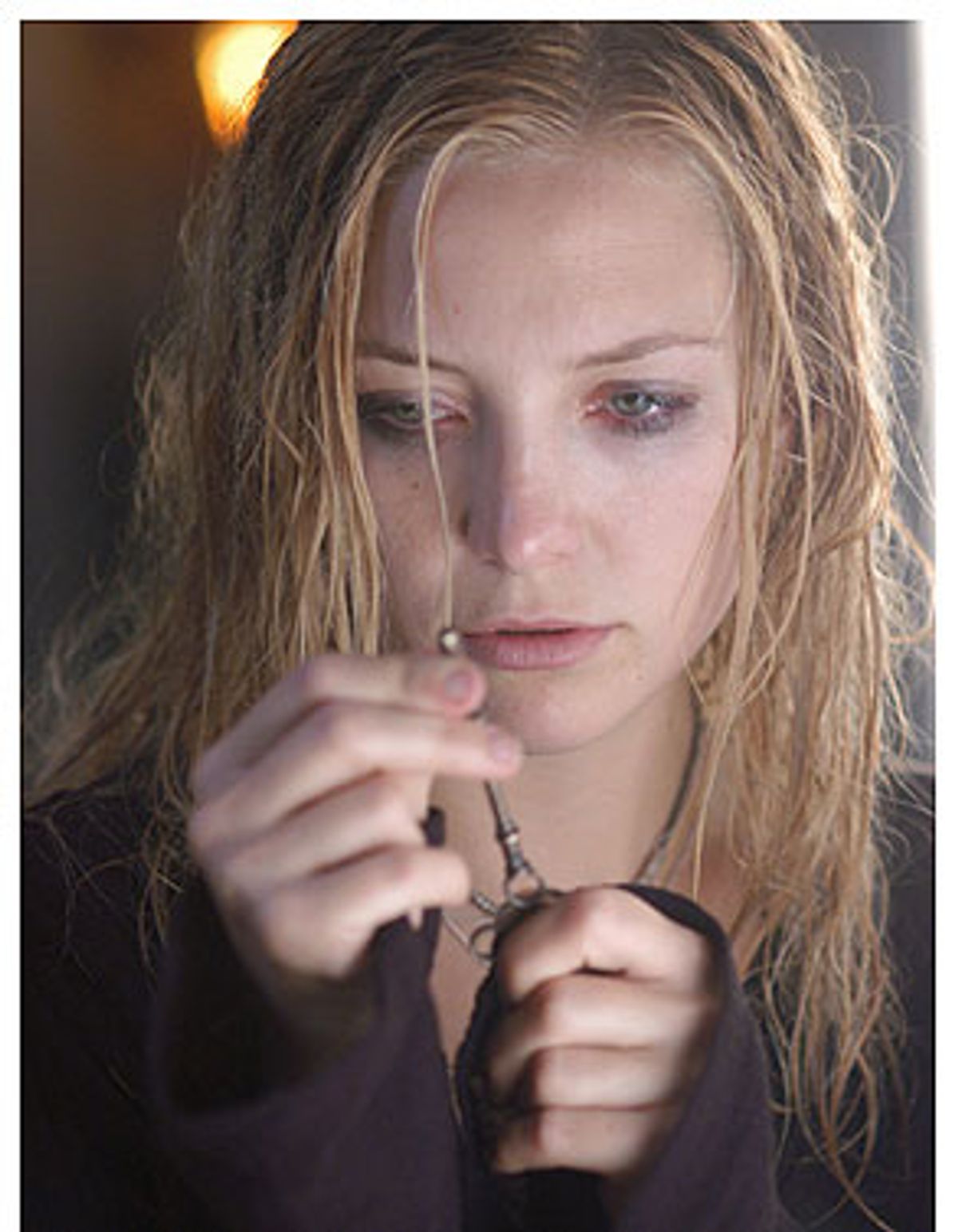

But with "The Skeleton Key," we're clearly in the hands of someone who knows what he's doing, and this time, we're having fun. The performances don't hurt: Rowlands gives us polite Southern graciousness with enough sinister undertones to keep us guessing -- is she a genuine bad 'un, or just fruity and reclusive? And Hudson, in addition to looking lovely in those skivvies, is given a far more interesting vehicle than the dumb romantic comedies she's been saddled with: Her character is a sunny idealist who dreams of becoming a nurse, but Hudson also shows us the dark, muted layers of determination beneath those ambitions. In this picture more than any other -- with the possible exception of "Almost Famous" -- I see the best qualities of her mother, Goldie Hawn, an extraordinary actress who sabotaged her own career by getting too hung up on being a beloved cuddlebug. There's lots of hope for Hudson, who, like her mother, is adorable, but who, also like her mother, has a flinty directness that's borderline intimidating.

No director yet has found the best use for Hudson, the role that will tap those terrifying and thrilling reserves that are just lying in wait. But Softley comes closer than anybody has. He always knows what he's doing -- he now needs more and better chances to actually do it.

Shares