The story line is as old as Midas: Greed corrupts; absolute greed leads directly to bankruptcy court. As we contemplate Enron's ascent to Olympus and free-fall into bankruptcy hell, it is all too easy to see the company's corporate arc as a metaphor.

Ain't karmic retribution a bitch? Enron execs didn't just cook their books with their state-of-the-art scams while lining their pockets with hundreds of millions of dollars of ill-gotten gains. As Robert Bryce recounts in his delicious disemboweling of the company, "Pipe Dreams: Greed, Ego, and the Death of Enron," Enron's high and mighty were also guilty of a host of more familiar, venial sins. They thought nothing of sending corporate jets to pick up homesick daughters from Paris, or to shuttle themselves to car races in Canada and the Masters Tournament in Augusta, Ga. They tried to charge their lunch-hour trips to strip clubs as business expenses. They publicly derided Wall Street money managers as "assholes" while simultaneously lying to the press, the public and their own employees. They cheated on their spouses and their shareholders.

And they got what was coming to them. Class action suits, criminal indictments, frozen bank accounts, congressional investigations, national and international humiliation. Story over: The Enron gang grabbed for too much, and they were slapped down for it.

Now Enron is the punch line to a joke, its mighty E sold at auction, its vaunted traders scattered to the four corners of the globe. For writers like Bryce, a veteran investigative reporter (and occasional Salon contributor) who convinced an impressive number of (unnamed) sources to dish him inside dirt, the rise and fall of Enron is a tidy package with a clear ending. Bad people, and, even worse, bad businessmen, sow the seeds of their own downfall.

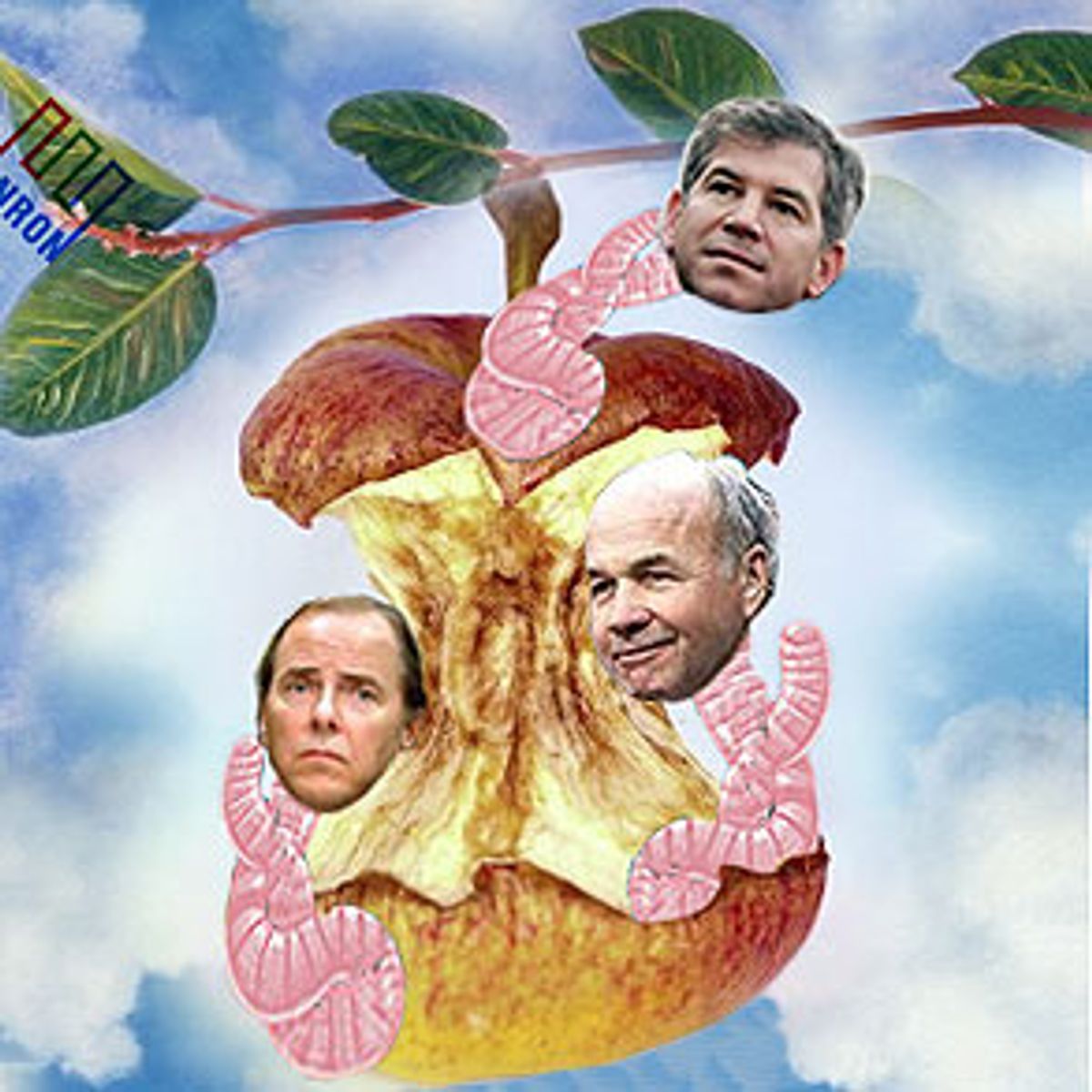

But the story isn't over. Enron isn't a metaphor, nor is it, as some would have us believe, a "bad apple," a rogue company that was out of control. Enron was the acme of a brand of unchecked capitalism that was almost universally embraced at the end of the '90s.

Bryce recapitulates how the press, the analysts, Enron's board of directors and its shareholders all bought into Enron's vision of itself. There were obvious reasons, as he points out, for the widespread collusion. The analysts worked for companies that also wanted Enron's investment banking business. The directors had companies of their own that were doing deals with Enron. The shareholders loved to see the stock price go up and up, and the business press, well, the business press loves a winner!

But the willingness of investors and analysts and bankers and reporters to go along and get along with Enron has deeper roots. Everyone wanted to believe in Enron's numbers, because more is better. We don't live in a society where 10 percent annual growth or 10 percent return on investment is enough. Nothing is ever enough, growth has to be faster, the profits bigger, the windfall larger -- and if you declare, like Enron, that your numbers are super-duper better than the best, then everyone's happy. No one wants to carp, to be a downer on the American dream.

As Bryce details, there were problems at Enron long before disaster overcame it, but no one outside the company bothered to take a close look until Enron ran out of tricks and was forced to declare a large quarterly loss. Then it all fell apart. If Enron had somehow managed to keep afloat, few people would care that Enron's executives yelled at their employees, slept with their secretaries or moved into really, really big houses. All that stuff is OK as long as you are reporting mind-boggling numbers.

Enron, in fact, is not an isolated case at all. Enron is everywhere. When media companies consolidate, seeking economies of scale at the expense of independence and creativity, it's because their shareholders are always demanding bigger numbers. That's Enron. When investment banks "spin" hot IPO stocks to their biggest clients, the goal isn't to help build a new company, it's to get 300 percent profits after a few hours of trading. That's Enron. When all the rules are lifted, and the government encourages businesses to do as they please, because, gosh darn it, regulation really puts a damper on the profit margin, that, more than anything else, is Enron too.

This is what happens when there are too few rules, too weakly enforced. Enron is no metaphor -- it is the embodiment of capitalism run amok.

By working fast and writing well, Robert Bryce has jumped out of the starting gate ahead of what is sure to be a couple of catalogs full of Enron books. Some will be more detailed, and some will likely take a broader view of Enron's place in the business universe. But few will be as much fun to read.

One chapter begins thus: "Oscar Wyatt was just plain mean. He was the kind of guy who'd sue his own brother-in-law. In fact, he did just that. Three times." At the beginning of another chapter, as he sets up an explanation of the evolution of Enron from mundane, plodding natural-gas pipeline company to high-flying "innovative" trading company, Bryce notes, "Face it, there's no sex in laying pipe."

There's plenty of sex in "Pipe Dreams." Robert Bryce is a rollicking writer in classic Texas gunslinger mode -- and it would be hard to think of a style more appropriate for a tale of varmints as lowdown as the Enron gang. Bryce has a rare ability to explain complex financial concepts clearly, combined with a breezy, colloquial style that makes his story a page turner. You could read "Pipe Dreams" at the beach, sipping a cocktail, and consider the day well spent.

"Pipe Dreams" appears to be compiled from two main sources -- every news article written on Enron in the last year, and scores of unnamed sources from the company, most of whom appear to be from middle management.

The inside sources add flavor, but if you have fanatically followed every iota of Enron coverage in the pages of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, you probably won't find many surprises. But that's not a drawback. Enron's story is so complex -- its venture into the international water business and its charge into trading financial derivatives are both worthy of books in and of themselves -- that just being familiar with the headlines as it unfolded in the newspapers is unlikely to be helpful in understanding how the whole mess unraveled. Bryce excels at fitting all the pieces into a compelling, if a bit breathless, story line.

In that story line, there is one central villain, and one compelling problem. The villain is Jeff Skilling, who took over as Enron's chief operating officer in 1996 and briefly served as CEO before stunning the financial world with his resignation in August 2001. The problem is Enron's consistent failure to generate enough cash to pay for the company's ongoing expenses.

Ken Lay mostly appears as a kind of absentee owner, more concerned with pursuing a political agenda of deregulation and hobnobbing with bigwigs than with actually running his company. One of the more interesting early chapters in the book concerns an incident in 1987, when rogue traders in the town of Valhalla, N.Y., committed Enron to contracts for millions of barrels of oil that Enron couldn't afford to deliver. The fiasco, writes Bryce, almost wrecked the company.

Ken Lay claimed to have been unaware of what the traders were doing. But he did note that "oil trading is a very volatile, very risky business. I would not want anyone to think at any time in the future this kind of activity would affect our other businesses."

In 1987, Enron was saved by some quick thinking and hard work by its executives. But a decade later, those executives were gone, replaced by a new generation of rogue traders whose main approach to covering up a big hole was to dig another, deeper one. And Lay's failure to keep tabs on what they were up to proved catastrophic.

Bryce devastatingly documents how Enron failed miserably at generating income from the plethora of new businesses it entered. It took a bath from its water and bandwidth trading escapades. It sold off some of its most dependable revenue-generating assets, such as its gas exploration and production unit, and poured hundreds of millions of dollars into its online trading business -- which may never have made a profit at all.

Anyone who has paid even the scantest attention to the Enron debacle is aware of the off-balance-sheet partnerships created by Andrew Fastow that blew up in Enron's face in the fall of 2001. But for Bryce, the main break in the Enron saga came when Jeff Skilling replaced chief operating officer Rich Kinder in 1996. From that point on, cost controls were out and reckless trading was in. From that point on, Enron hemorrhaged cash. But Skilling covered it all up, and set the stage for future disasters, by pushing Enron to employ a technique known as "mark to market" accounting.

In "mark to market" accounting, the full value of a long-term deal is booked as immediate revenue. So, if Enron signs a deal to provide natural gas to a power company for 15 years, with the power company agreeing to pay, say, $10 million each year, Enron gets to book $150 million in revenue immediately, even though it won't actually see the bulk of the cash for years to come.

Those bogus revenue figures covered up the losses that Enron incurred as it tried to move into new businesses. At the same time, Enron's cash crunch forced it to borrow billions of dollars from banks. Fastow's notorious off-balance-sheet partnerships also allowed Enron to shift hundreds of millions of dollars of additional debt off its books, thus maintaining the facade that the company was an income-generating colossus.

Ironies abound. CFO magazine named Fastow "Chief Financial Officer of the Year," and the business press continually labeled Enron one of the best-run companies in the country. Yet all the while the company was incapable of doing the one thing that you expect well-run companies to do -- make money.

Even better, there is the case of Wendy Gramm, wife of Sen. Phil Gramm, R-Texas. As head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Gramm was instrumental in getting the rules changed so that Enron could trade energy derivatives without any government oversight. Then she quit her job at the CFTC and was immediately given a well-compensated seat on Enron's board. As Bryce notes, if she hadn't gotten that exemption passed, and Enron had been prevented by government regulations from setting up some of its dubious derivative deals, the company might still be solvent today.

Bryce intersperses his explanations of Enron's cash troubles, derivatives schemes and off-balance-sheet partnerships with thick dollops of juicy gossip. "Pipe Dreams" probably contains more than readers need to know about the sexual liaisons of Enron executives with lower-ranking employees, or executive Louis Pai's fixation with strippers, or the exact sums of money wasted on unnecessary uses of the fleet of corporate jets.

But when Bryce writes of Ken Lay's affair with his secretary Linda Phillips that "His marriage to Linda would help define Enron's culture," the moralizing gets a bit thick. Sure, it's salacious -- as it turns out, there was plenty of sex involved in laying pipe -- but it is also distracting.

A fixation on the sex lives of Lay and Skilling and other Enron executives leads easily to the proposition that Enron failed, not just because it was badly run, but because the people who ran it were bad people. In this view, Enron was fundamentally different from its competitor Dynegy, where the executives boasted about their long marriages to their first wives. Enron's culture was uniquely corrupt -- it rewarded cheating, lying and browbeating like nowhere else.

But that misses the point. Enron didn't occur in a vaccuum. The hordes of freshly minted MBAs from Harvard and Wharton and Chicago who were banging on the door to get into Enron were not transformed into evil rapscallions by their employment with Enron. The law firms and accounting firms and investment bankers who signed off on Enron's deals didn't do it because they were hornswoggled by a few bad apples.

Decades of deregulation, of the mantra that the "market knows best," of the elevation of quarterly profits into the next best sign of godliness, led us directly to Enron. It is, perhaps, possible to argue that Enron's executives conducted their skulduggery with a flair unmatched in corporate America, but the closer one looks at Tyco and WorldCom and Global Crossing, the less exceptional Enron seems to be.

In your run-of-the-mill Greek myth, the gods strike down those who aspire too high, who get carried away with their delusions of pride and grandeur. Right now, Enron looks for all the world like it has been zapped by a barrage of Zeus' lightning bolts.

But Zeus missed his target. Who would have been pleased as punch to have owned some Enron shares in 1999? Just about everyone. Who changed the rules so that investment bankers, accountancy firms and Enron wannabes could do as they pleased? Elected politicians. And who elected those politicians? We did.

We're getting just what we asked for.

Shares