Now that the dead are gone (though their bodies still lie in pieces, yet to be recovered, among the ruins), we are daily exhorted to celebrate their wake with more vigor, to abandon the restraint that the events have imposed upon us. Or, more accurately, the restraint imposed on our wallets.

Hotels, airlines, resorts, restaurants -- addicted to an uninterrupted stream of customers and frivolity -- are in a thoroughgoing panic less than three weeks after the most shocking attack our country has ever experienced. Their profits are down; they say their businesses are tanking. Aware that pandering to customers in the same old fashion seems in bad taste, they have turned to patriotism to ease advertising's return. Thus, the sell is less self-consciously intrusive, perhaps less insistent than in days of old. It is a bit softer, more reverent in a maudlin sort of way.

But, to borrow a phrase often used by President Bush, "make no mistake about it": It's still the same old sell. Thus, the administration encourages us to get on a plane and go to Disneyworld to put America "back to work." Fancy clothing manufacturers plaster their display windows with flags, inserting fashionable fall merchandise among the folds of Old Glory, reminding us that to buy a new pair of leather boots is to do one's part to get the economy back on track.

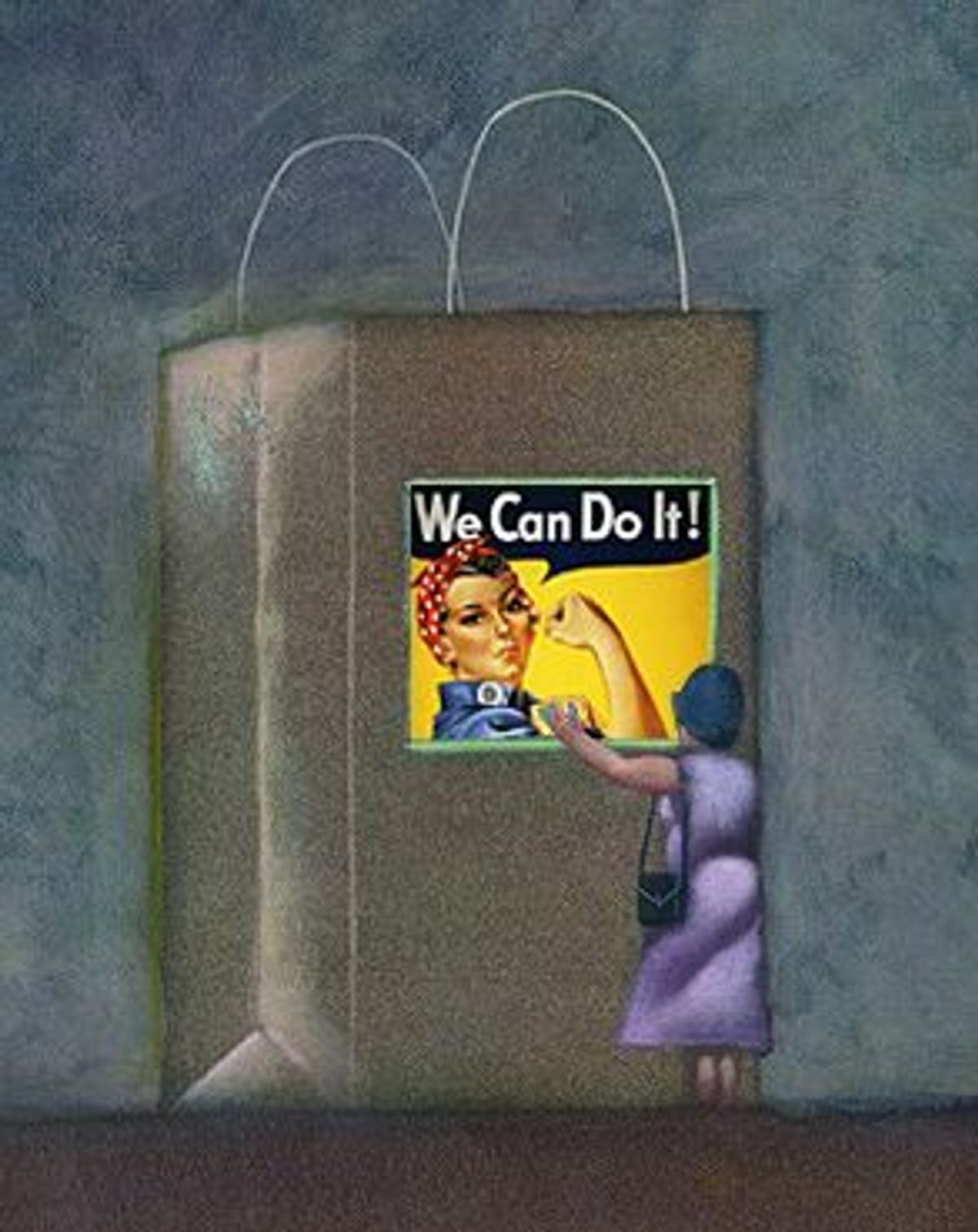

Forget the rivet-gun, Rosie! Shop!! The New York Times, in its "Pulse" section of Sept. 30, notes that for $32 we, too, can acquire the loungewear of choice "for New Yorkers who feel better staying at home just now": "skinny scrubs," knockoffs of the medical professionals' standard, are alluring in light blue and made particularly attractive by their "trimmer, slightly boot-leg cut, which minimizes hips and thighs." (The author thoughtfully acknowledges that concerns about hips and thighs might not be "uppermost" in our thoughts as we "stagger to the newsstand" in the morning.) The toll-free number to order is provided. Anxiety might keep us at home, but shopping (and our "pulse"?) can go on unabated. Whether it's a trip to fantasyland or fantasies about private retreats in one's pajamas, the airwaves and newspapers are full of options to make us, the people (otherwise known as the economy), feel better and "get back to normal." Retail therapy for a nation.

At best, this rhetoric sounds shrill and starkly highlights the most grasping aspects of our national culture. At worst, it threatens to turn us into cannibals, feasting upon ourselves out of panic that the famine is about to set in. Where in all this is the dignity borne of mourning? In the wake of all our losses, do we have no greater sense of our purpose than to get people to spend money, pathetically chasing consumer goods in an attempt to salve our wounds? Where is the time of quiet, of reflection on life, that death should always bring? We should consider our impulses carefully, for they are the best evidence yet that we have already surrendered the freedom that we say we want to defend. Slaves to the mall, to our own consumption and that of our neighbors, we find our liberty to abstain has been eroded. Such restraint is not tolerated, but is feared, even abhorred by some as unpatriotic.

But traditions of mourning rightly distance us from the patterns of everyday life; they offer us a way to live out, symbolically, our sorrow, to represent publicly the change that the loss has brought upon us. We are told to be patient in the war to come; let us also be patient with ourselves -- as human beings, not automaton-like economic actors -- as we strive to understand how to live in light of this loss. Nothing we can buy will provide the space for that reflection, although the demand that we do so could well demoralize us even further.

Shares