Brewster Kahle may be the last Silicon Valley tech entrepreneur in the waning days of 2001 who isn't embarrassed to boast about his Big Idea. Maybe that's because he's not trying to make any money with it.

"The last time someone really tried to do this it was 2,000 years ago. It's the chutzpah of the Greeks," he bragged at the launch party for the Internet Archive Wayback Machine on Oct. 24. "There are only 5 billion people in the world and they can only be typing 60 words a minute, 24 hours a day. So, that bounds it," he said to an admiring audience of librarians, academics and computer scientists gathered at UC-Berkeley's Bancroft Library.

Kahle, the founder of the Web "navigation company" Alexa, started the nonprofit as a side project five years ago. The idea was simple: to preserve the notoriously ephemeral Web by grabbing as many pages as possible and storing them for history. So far, the archive holds more than 10 billion Web pages dating back to 1996. "Our opportunity is not only to have it all, but to make it widely available. That is the opportunity of our time," he crowed.

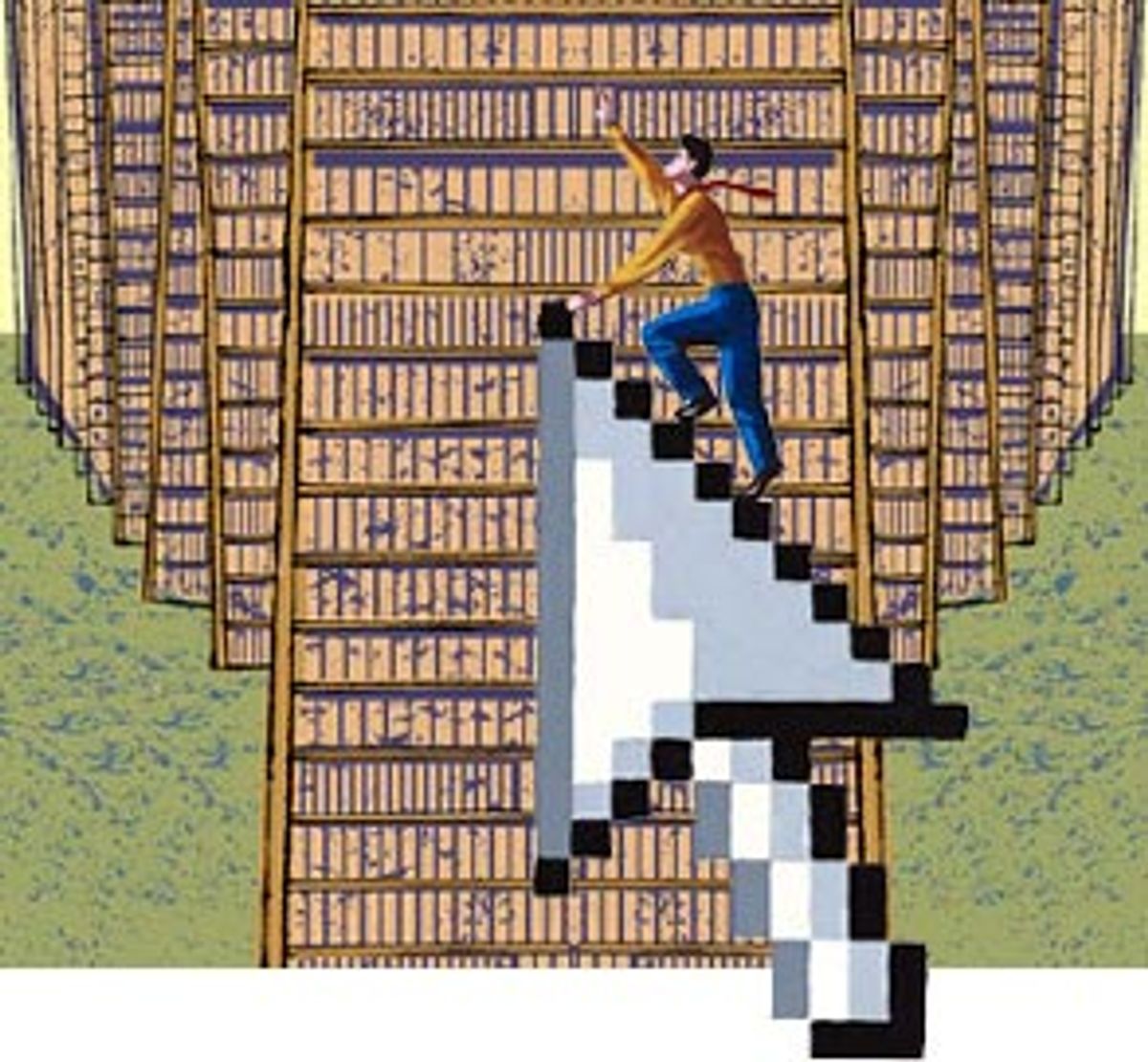

The opportunity of our time! It's been a while since anyone has been willing to pump out some of that old-school hyperbole so familiar from the Internet hot-air balloon of the late '90s. But that's not all. "The idea of making all knowledge available to anyone on the planet is the democratic ideal," Kahle said.

It's certainly a very geeky version of the democratic ideal -- tons and tons of unsorted data. Quantities of such scope that it's measured not in megabytes or gigabytes, but terabytes -- 100 of them, which adds up to about 100 trillion bytes. And it's an ideal that has attracted a lot of excitement from a tech press corps desperate to find something to pay attention to in the post Sept. 11 era.

While Kahle and his co-conspirators have been putting the pieces of the archive together for five years, the debut of his new Web interface -- the Internet Archive Wayback Machine finally makes traveling back in time in the history of the Web as easy as using a search engine. In its early weeks online, the Wayback Machine has proved so popular that the site's Web servers are laboring mightily: The home page has been broadcasting an apology: "Warning: Service intermittent. We apologize for not anticipating the usage this service is receiving. We are working on adding servers, but this process will take weeks. Again, we apologize."

That very popularity could threaten more harm to the project than just overloaded servers. Kahle's geeky democratic ideal -- all the information! for everyone! all the time! forever! -- is the same formula that has made so many other Internet utopia engines -- think Napster -- run headlong into the restrictions of old-fashioned copyright law. And while in the last five years the archive hasn't attracted much attention from the copyright cops, it's also true that its 100-terabyte holdings hadn't previously been just a click of the mouse away.

Kahle says that he and his cohorts have now unleashed on the Web-surfing public nothing less than the largest collection of human words ever, bigger even than the Library of Congress, which the Wayback Machine is affiliated with. Of course, those words are not limited to the great works of the literatures of the world, but include a mess of just about anything one could imagine, including millions of pieces of marketing literature from now-defunct companies and the early versions of uncounted confessional personal homepages.

So with a little digging, you can learn that on May 11, 2000, Pets.com offered this bit of wisdom: "Word to the wise: Beware -- pooper scooper laws vary." Or that May 5, 1999, was Jenni of JenniCam's first day at a new job: "Mostly I just watched videos," she mused in her journal. "On the Job Safety, Our Corporate Vision, How to Sell, stuff like that. I haven't worked retail since high school."

But as any cultural relativist or American studies major knows, it's just such banal ephemera that counts, if you have enough of it. Beyond sheer novelty, there's a social value to preserving these cultural artifacts. In the future, perhaps they'll reveal more about us and the early Web than we could ever imagine. And while the bulk of the archive can be compared to a library of millions of digital brochures and scrapbooks, there are also featured "collections" of pages designed to show off the more serious artifacts as well: the Web news coverage as it happened on Sept. 11 and the way that some of the pioneering sites on the Web looked in 1996. There's certainly lots for researchers, scholars and pop culture fanatics to wade through. And there will surely be lots of writers and graphic designers searching for the remnants of their own hard work, now vanished as a result of publishing Web sites gone missing.

Then there's the pure nostalgia factor. Old mouse-hands will grow misty as they contemplate the good-old Ultimate Band List as it was in late 1996, or Amazon.com, that humble online bookstore, light-years before the smiley logo grinned its first evil grin on Jeff Bezos' quest for world domination of all "e-tail" everywhere.

At first, it's hard to see how anyone could object to such a historic preservation project. One of the maddening paradoxes of the Web has always been the odd reality that once something makes it online, it can't be taken back, and yet an individual page or site might disappear at any moment. But making the Wayback Machine freely available to all comers poses several legal problems.

The archivists are fond of using the metaphor of a library for the archive, and in its early years, it did function like a library, albeit one with closed stacks. It was a huge body of information that could only be accessed by sending a request to engineers who would pull out the relevant volumes. But now that it's online and free to search by anyone, the archive is more like a shadow Web, another version of the Web that's effectively republishing huge amounts of data from sites irrespective of copyright law.

It's a conflict that the founders of the archive are well aware of, one that led Lawrence Lessig, a law professor at Stanford, to rally the troops at the Internet Archive Wayback Machine's launch party with this amusing call to arms: "I join your fight against the students that I produce."

There are already some sites that refuse to be included in the archive. Sites can keep their pages off-limits either through password protection or robot exclusion, simply by automatically rejecting the software robots that specialize in indexing the Web. For instance, although some of the New York Times home pages can be found and searched in the archive, the stories themselves, as they ran, are not available.

Any Web page that is password protected is also inaccessible, which is likely to have an increasing impact on the future quality of the archive's collection as more and more commercial sites try to make money through subscriptions rather than advertising. But it's also likely to cause controversy with newspaper sites like the San Jose Mercury News, which offer free access to new stories, but make readers pay for archived material. Why pay up if you can already find the story for free at Archive.org?

"We're sure that there are going to be a lot of people who want to be excluded," says Kahle, although he notes that in the Internet Archive's five-year history 90 percent of the complainers have become converts after hearing that the nonprofit's primary goal is simply to preserve history, not to profit off it. Kahle says it has typically been individuals, not companies, who are most concerned about protecting their intellectual property -- or future privacy.

The Internet Archive's nonprofit status may help it avoid some legal challenges, but it is still not immune from basic copyright concerns. The problems that arise aren't likely to be entirely solved by blocking access to individual sites within the archive. That's because the copyright to the content of any given site doesn't necessarily reside with the operator of that site. For instance, a wire service, such as the Associated Press, might balk when it discovers that thousands of its stories, published on other sites, can be freely visited in the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. The testy members of the National Writers Union may also view the archive as an unauthorized and uncompensated republishing of their work. There's also the tricky question of what happens if a settlement in a lawsuit requires that libelous material be removed from a Web site, yet the original lives on in the archive?

The Internet Archive Wayback Machine may be ready to take us on a mind-blowing sojourn into the digital past, but it may have less success delivering us to a less litigious future.

Shares