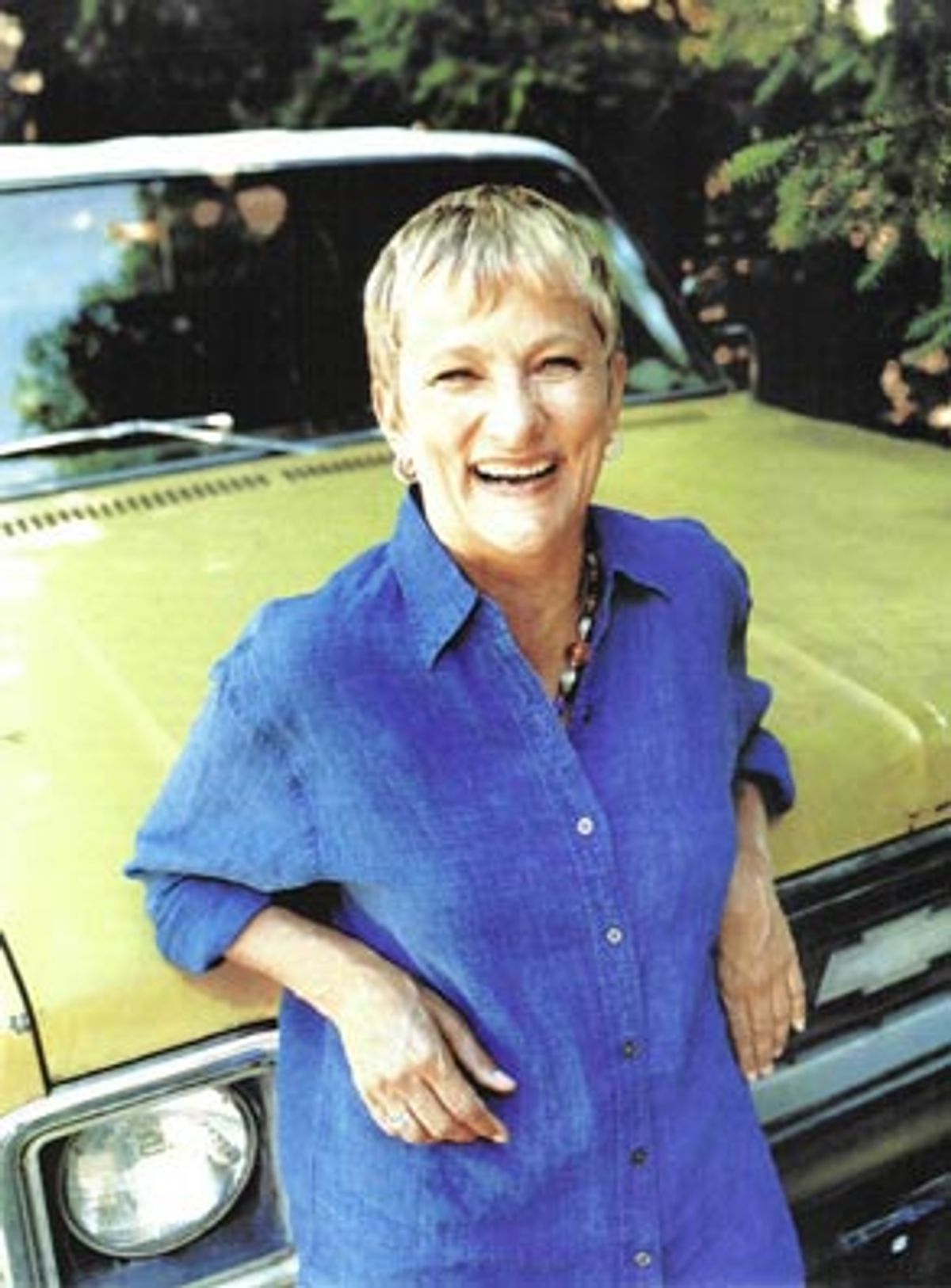

Anita Borg, a Silicon Valley computer scientist and influential advocate for the involvement of women in technology, died of brain cancer on Sunday, April 6, at her mother's home in Sonoma, Calif.

Her colleagues mourned Borg's passing, even as they stressed how crucial she was in creating a kind of collective consciousness for women working in the heavily male-dominated field of computer technology.

"It's impossible to overstate her role in creating a community of female computer scientists that has helped students and professionals stay in the field, organized to bring more women in and helped people achieve their full potential," said Ellen Spertus, a computer science professor at Mills College.

The founder of the Systers mailing list, the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing and the Institute for Women and Technology, Borg was just 54 years old.

In the punny parlance of geeks everywhere, Borg liked to joke that she was her "systers keeper," since she'd started the Systers mailing list -- that's "sisters" in "operating systems" -- an online communications forum that now has some 2,500 members in 38 countries.

Fittingly, that mailing list grew out of a conversation in the ladies' room. At a major operating systems conference in 1987, Borg and several other women observed how few women were at the conference, not to mention in the overall field of computer science. Borg invited the 25 female attendees at the conference (out of a total of 400) to have dinner together, and started the mailing list to keep the conversation going. It hasn't stopped since.

Borg also co-founded the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing, which brings together top women in the field to give papers about technical topics. Last year's conference drew some 630 attendees, from 7th and 8th graders to women in their 70s.

"When you worry about how few women there are in computer science you can look at the barriers that women face, but she took a completely different approach. She knew it could be a positive experience for women to meet other women who are doing well in the field," says Maria Klawe, dean of engineering and applied science at Princeton University and president of the Association for Computing Machinery. "The first Grace Hopper Conference was just a transforming experience for everyone involved. I think we were just blown away. For all of us, it was the first time in our lives we'd been in a room with 400 other technical women."

Borg was a research computer scientist, whose own work was in fault-tolerant operating systems and microprocessor memory systems; she spent 11 years working in research at Digital Equipment Corporation, where she once threw out her scheduled remarks for an internal conference and instead made an impromptu speech on the topic of "Why There Are Only Seven Women Left in Research at Digital."

She was a proud second-wave feminist who wore a T-shirt that said: "Well-behaved women rarely make history." At a National Science Foundation gathering in the late '90s, she threw out a challenge -- Borg's own "moonshot" -- that she called "50/50 by 2020." She wanted to see half of all computer science degrees go to women by 2020.

But as Borg worked in the industry to bring that dream to fruition, she simultaneously fomented a much more radical goal than mere gender parity. She argued that to achieve the creation of socially valuable technology, the users of the technology must shape its development, and not just the (mostly male) computer scientists.

"She was the first woman who really said that women should create the tools of society, not only technology, but machinery, every kind of tool, because the people that design those tools determine how they should be used, and ultimately control society," said Sylvia Paull, the founder of GraceNet, an organization for women in technology.

"What if only 30-year-old women developed technology?" Borg told me in an interview in 1999. "All of it -- and that technology was geared mainly for 13-year-old-girls? Technology would be out of whack, out of balance. But that's the world we live in: Men hold the power, and boys drive the market.

"Technology is not neutral," she added. "Every invention reflects the values, perspective, background, and needs of its inventor. The variety and impact of new digital technologies will depend on the extent to which women are involved and their needs are taken into account. Technology is going to change our political, economic, social and personal lives. Women need to be there saying: 'This is how we want things to change.'"

In the late '90s, when it seemed as if everyone in Silicon Valley was fixated on stock option millions and dazzling IPOs, Anita Borg went to Xerox PARC, the venerable research facility, to found a nonprofit -- the Institute for Women and Technology. There, she strove to change how new technological ideas were created, not just by encouraging women to become computer scientists, but also by finding novel ways for the "nontechnical" to influence technological development.

"Being a visionary is kind of easy, but to be a visionary and execute that vision is very rare, and she was one of those rare people," said John Seely Brown, then director of Xerox PARC.

"She believed that anything was possible, and she created environments where that was true," says Denise Brosseau, co-founder of the Forum for Women Entrepreneurs.

Personally, Borg was known for her high-octane approach to having a good time. She took up motorcycle riding in the '70s, white-water kayaking in the '80s and learned to fly a Cessna 152 in the '90s. While working at Xerox PARC, she mountain-biked every day in the Silicon Valley hills around the bucolic campus.

In the last months of her life, Anita Borg was offline. But she wasn't out of touch with the community that she'd brought together.

"Anita's been getting hundreds of letters from women all over the world," said Telle Whitney, a longtime friend of Borg's, and co-founder of the Grace Hopper conference and current president and CEO of the Institute for Women and Technology. A typical card would read: "You don't know me, but I can't tell you what a difference you made in my life. When I heard about you, I knew that I was not alone. I joined Systers in 1992, and it was the first time that I had a community that I could talk to."

Shares