The directions Kenneth and Gabrielle Adelman give to get to their home are inaccurate, on purpose.

The flaws theoretically make it easier to find the couple's 4,200-square-foot house in Corralitos, Calif., located in a gated enclave in the hills just south of Santa Cruz. After I drove up a narrow mountain road past twisty live oaks and a flock of wild California quail, I learned that the distances indicated on the directions were just a tad shorter than they actually are on the road. Ken explains that they've shaved off a tenth of a mile from each leg of the trip to get guests to look for that next turn in the road just before it appears.

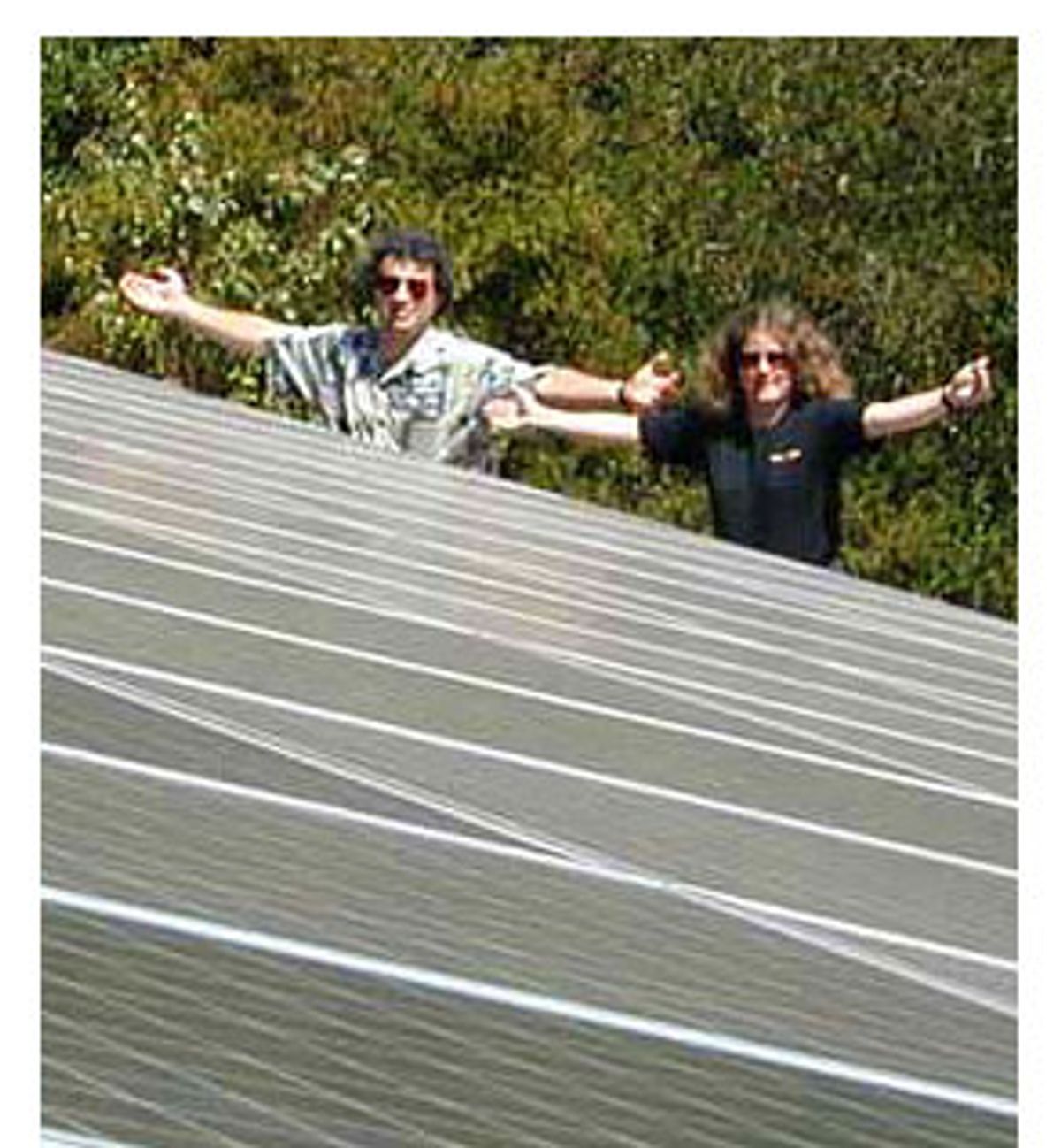

It's a tiny hack of human behavior, social engineering through clever manipulation of data, typical of the two Caltech grads who live here. Kenneth Adelman is a retired tech entrepreneur in his 30s who sold his last company to Nokia for millions in stock; Gabrielle is the bookkeeper for the Santa Cruz Flying Club, where the couple are avid aviators.

The Adelmans do things differently, if in their judgment it means doing them better. Even if that involves going head to head with the power giant Pacific Gas & Electric or to court with a celebrity like Barbra Streisand.

The Adelman's entire house is a vast experiment in alternative energy, but you'd never know it just by seeing it. Five miles inland from the Pacific Ocean, on California's Coast Range, the house is situated in golden, oaky hills. So spacious that it includes an entire guest wing the couple rarely uses, the house is hardly the centerpiece of the property; it's the landscape that dominates, dotted with live oaks, yielding to sweeping views of the surrounding forested mountains, down into the populated valleys of Watsonville.

On a sunny day like the one on which I visited, this expansive, multimillion-dollar home, the air conditioning, even the heated pool and hot tub outside, are all powered by the sun. The three electric cars in the Adelmans' garage also, indirectly, get their electricity from the house's primary energy source, a 2,880-square-foot solar array, which sits some 600 feet downslope from the home, out of view, on a south-facing hillside. This system, including backup batteries, cost $360,000 to build (although the Adelmans received a $135,000 rebate from the state government as a partial subsidy.) It was thought to be the largest such residential system in California when it was installed in 2001, and has a theoretical output of 30.5 kilowatts, but really produces more like 27 kilowatts in sunny summertime production.

The Adelmans are environmentalists, but one of their favorite hobbies is flying their own planes and helicopter, which means that their fossil fuel consumption is not insignificant. Gabrielle decided that with all the flying they were doing in their private aircraft, they should find other ways to mitigate their own contributions to environmental pollution and global warming. That led them to purchase the electric cars, which in turn sent their electricity bills skyrocketing. So they decided to go solar.

But the Adelmans aren't living off the proverbial grid. On the contrary, they're engaged in a symbiotic relationship with the power grid, feeding energy back to it, as well as drawing down from it. The system that powers their house, a set of solar panels designed by EcoEnergies of Sunnyvale, Calif., generates so much power when the sun is shining that the Adelmans feed power back to the grid. They only draw power from the grid at night, when it's dark, or when the weather is bad. In a process known as "net metering," the excess energy their solar system produces during the day serves as a credit so that they can light and heat their home at night, as well as charge up their electric cars when they're least likely to be driving them, and when overall power demand is at its lowest.

The Adelmans are obviously not a typical family -- and the example they set is not easily duplicated. But they are vigilant and innovative about reducing their impact on the environment. They subscribe to the belief that alternative sources of energy coupled with the right kind of technological innovation can deliver a better world, if the entrenched interests would just get out of the way. And if they won't, it's worth fighting them.

To get their solar system online feeding power back to the grid, as well as into their home, the Adelmans had to fight Pacific Gas & Electric before the Public Utilities Commission, as well as endure having their power shut down during the dispute. But with their own home, they've managed to show just how far individuals can go, if they have the means, toward changing patterns of power consumption, even while maintaining all the trappings of a retired tech entrepreneur's lifestyle. In an era when gas prices are climbing with no end in sight, their example is more relevant than ever. And if new legislation currently before the California state Assembly passes, many other Californians will soon be living in homes a little more like the Adelmans'.

The Adelmans are best known for their fight with Barbra Streisand. The chanteuse took exception to their nonprofit, Web-based conservation effort, the California Coastal Records Project. The CCRP documents the state's coastline from the Oregon to the Mexican border with more than 12,800 photos that the couple snapped from their personal aircraft. The goal is to maintain a permanent, publicly accessible physical record of the coast as a weapon against illegal development.

Streisand, whose sprawling Malibu estate appears in one of the photos, decided she didn't like her house, pool and backyard showing up online, so she sued the Adelmans and their Internet service provider for $10 million in May 2003, alleging invasion of privacy. Streisand did not prevail in court, however; a Los Angeles Superior Court judge ordered her to compensate the couple $177,107.54 in legal fees and court costs.

The spat with Streisand is really little more than a footnote to the Adelman's overriding passion: their commitment to alternative energy sources, solar power in particular. But the two things are connected: According to the Adelmans, their heavy use of fossil-fuel-burning airplanes and helicopters for their conservation project made them feel so guilty about their impact on the environment that they decided to compensate for their profligacy in other ways. So they went on an electric car buying frenzy.

Ken was skeptical at first, but found that as soon as he got behind the wheel of an electric car, "I was absolutely hooked." He's now convinced that electric cars aren't just better for the environment, "they're better cars." The hassle of charging them up at night seems minor to the Adelmans, especially compared to the effort of going to a gas station: "I don't have gas at my home. I only have electricity," quips Gabrielle.

The couple first leased two (now recalled) EV1s from General Motors. Then came the purchase of two Toyota RAV4 Electric Vehicles. Toyota no longer sells the RAV4, but the Adelmans have held on to theirs, along with an AC Propulsion tzero.

The Adelmans became so hooked on their electric cars that the battery in their Miata died from lack of use after they let the convertible sit in the garage for a month and a half. Now, says Gabrielle, they religiously start up their conventional cars every month, whether they want to drive them or not.

U.S. automakers may have largely abandoned electric cars, but the Adelmans predict that Chinese auto manufacturers will take up the slack, given that nation's surging production of consumer electronics, and rising middle-class demand for cars.

But even as the Adelmans became evangelists for electric cars, they kept hearing a common objection from green-conscious skeptics. The cars might have zero noxious tailpipe emissions, but that didn't mean they were blame-free. "That just means that you're not polluting here,'" Ken says he was frequently told. "'Have you just moved the pollution to [the power plant at] Moss Landing?'"

The Adelmans reject the critique, arguing that generating electricity at a power plant is more efficient than fueling up individual cars at gas stations, particularly when one factors in the environmental impact of extracting, refining and transporting gasoline. There's also the benefit of not contributing to the financial and political costs of depending on foreign oil. Still, the Adelmans wanted to remove even the slightest stain of suspicion. They decided to reexamine the potential of solar power, a technology they'd considered for their home in 1998, but decided wasn't feasible in terms of cost or efficiency.

But by the early 2000s, the price of solar power technology had begun to fall significantly. In the intervening years, the Adelmans' move to electric cars had also dramatically increased their electricity use at home. The combination of the two factors started to mean that moving to solar would make financial sense, especially when one took advantage of California state subsidies for the use of the technology. There was one additional complication: The roof over their sprawling mansion juts up and down at varying terraced heights over different parts of the house, so a conventional rooftop system of solar panels wouldn't work. Nor did the Adelmans want to place the panels next to their house, because that would require chopping down native live oaks.

They eventually ended up with a giant black array of panels, located well down the hill from their house. Next to the panels, one live oak casts a bit of shade on the huge array, but Gabrielle won't let Ken cut down that tree to make the system more efficient. In this, as with every other ecological choice, there are always trade-offs. But as their Web site brags: "No oak trees were harmed in the process."

The Adelmans say that even though their system cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, the combination of their large power demands -- charging up their fleet of electric cars increased the cost of their electricity bills to $1,000 a month before they built their solar power system -- and skyrocketing energy prices would have ensured that they could have paid off the costs of the system in nine and a half years.

That is, if they hadn't had to fight the local power utility to get the system up and running. The problem was net-metering on the scale that the Adelmans demanded. PG&E refused to permit the practice -- in which excess power from the Adelmans' house was contributed to the grid -- for a system capable of generating more than 10 kilowatts. Even though California was in the throes of a massive power crisis at the time, the power company balked.

"PG&E doesn't want any competition," says Gabrielle, flatly.

California had recently raised the allowable limit for residential homes from 10 kilowatts to 1 megawatt, but the Adelmans soon found their system caught up in a blizzard of red tape. PG&E threatened to charge them $605,000 for upgrades to the local power distribution system to make interconnection to the grid feasible. (Ultimately the utility only charged $11,000.)

The pushback galvanized the Adelmans. "Whether I was just the first applicant of a system over 10 kw, or whether they somehow picked me out special for this treatment, was unknown to me, but a battle they wanted, and a battle I was going to give them," writes Ken on his Web site. "Besides, I had nothing to lose -- the solar system was already constructed and ready for operation."

"There are a lot of people who don't have the resources to fight back," says Gabrielle. But they did.

The summer of 2001 marked the high-water point of the California power crisis. PG&E declared bankruptcy, and Californians were being scolded to turn off lights and do laundry at off-peak times to avoid rolling blackouts. As Ken remembers on his Web site: "Pacific Gas & Electric was bankrupt from having to pay outrageous wholesale prices for peak-time power, and here I was willing to give them peak-time power in exchange for kilowatts that they would deliver to me at 2 a.m. to charge my cars. They were acting not just against the best interest of the public, but seemingly against their own best interest!" When local media stories in the San Jose Mercury News and the Santa Cruz Sentinel broke, the power company temporatily capitulated, approving the system. But then it revoked that approval just days later, forcibly disconnecting the Adelmans' house, putting them effectively off the grid. The Adelmans ended up spending months engaged in costly dickering before the Public Utilities Commission, before finally bending PG&E to their will.

Today, the Adelmans generate so much electrical power that they host Web servers for their friends for free just to use some of the excess. Their goal: At the end of the year they want to have the amount they've fed back to the grid during the peak hours during the day balance out exactly the amount they've used at night charging up their electric cars. Although PG&E will charge the Adelmans at year's end if they've consumed more power than they've generated, the company won't allow them to roll over any positive credit from year to year.

The Adelmans now live a lifestyle that few can claim to emulate, literally driving and living with sunlight. It's a shame that as yet there are no electric helicopters available for their use in taking photos for their Coastal Records Project. But as they point out on the project's Web site, the Robinson R44 helicopter they fly gets about 13 miles per gallon, "approximately the same as most SUVs on the road today."

"We're aware that we burn fossil fuels operating our helicopter, and sincerely believe that the environmental good that will come from this project far outweighs the bad," they write. "Furthermore, we have almost completely eliminated our use of fossil fuels in our terrestrial transportation by driving electric cars which we charge using our photovoltaic solar system."

Can the average Californian duplicate the example of the Adelmans, without the benefit of having sold a technology start-up right before the dot-com crash? It's possible, with a little help from the government. The California Legislature is currently considering a bill to help Californians -- and not just the wealthy, technocratic elite -- embrace solar technology without having to fight the power company to pull it off, by mandating that solar power be built into new construction.

"Thousands of homes are being built in California every year, and they're being built without solar power, and we think that's a missed opportunity," says Bernadette Del Chiano, an energy advocate for Environment California, a nonprofit group that is lobbying for the legislation. "We should start to build solar in as a standard feature on new homes where it makes sense."

The bill, S.B. 1652, was passed by the California state Senate, and is now in committee before the state Assembly. It would require that, starting in 2006, a yet-to-be-determined percentage of all new homes in sizable new developments be required to get some of their energy from solar panels on the roof. According to the California Building Industry Association, in 2006 about 135,000 single-family homes will be built in California.

California is currently the third-largest market for solar power in the world, after Japan and Germany, according to Environment California. But even so there are just a few new housing developments scattered around sunny parts of the state, such as the Cherry Blossom subdivision in Watsonville, near the Adelmans, that market solar energy as a feature. Most solar systems, like the Adelmans', are installed on a one-off basis by environmentally conscious homeowners through costly retrofits.

Solar technology has fallen in price some 85 percent since the 1980s, but it's still subsidized by some forward-looking states in an effort to make it financially viable. Environmental groups, and the sponsor of the legislation, state Sen. Kevin Murray, a Democrat from Los Angeles, predict that the regulatory kick of this legislation could help costs come down even more.

"It's a technology that is coming down in price, and it's been around long enough to verify its value. If we jump-start the demand for it, the price will come down significantly," says Sen. Murray.

"It will make it mainstream, as opposed to the kind of high-tech, environmentalist niche that's retrofitting their homes. We need to get it into suburbia in a meaningful way," says Chiano.

The California Building Industry Association is opposed to the regulation.

"What the legislature in this bill is trying to do is accomplish an energy-savings policy on the backs of new home buyers. I think it's a little bit misleading to suggest to the public that for $20,000 a home, we're going to save enough energy to solve the state's energy problems," says Tim Coyle, senior vice president of governmental affairs for the association. "It's a promising technology, but an untimely and inappropriate tax on home buyers."

Del Chiano disagrees. The going price for a 2 kilowatt system retrofitted onto an existing house is now only $14,000, and the cost for a system built into a new house should be considerably less. By baking the cost of the solar system into a standard 30-year mortgage, she says, a homeowner would be breaking even or even saving money.

"Every time you tell any business what to do, they don't like it," adds Sen. Murray. "Anytime there is anything that costs them any money they say it must be horrible for the world. They're just inflating the costs, because they don't want to do it."

Tim Merrigan, senior program manager for the Zero Energy Homes Initiative at the National Renewable Energy Lab, which works with developers to voluntarily build solar into new homes projects in California, Nevada and Arizona, says that some of the developers he's worked with have been able to sell solar-powered homes at a premium. But he isn't enthusiastic about mandates: "This is something that the home builder can offer to the home buyer, and make a profit. Starting to say that it's mandatory maybe sends the wrong message to home builders."

To which the Adelmans, or any other socially responsible, energy-conscious consumer, might respond: The state mandates all kinds of details of home construction, from electrical wiring to smoke alarms to whether you can add a bungalow in your backyard. Why not mandate a cleaner future?

Shares