If the Bush administration won't fight global warming, California will. By any means necessary.

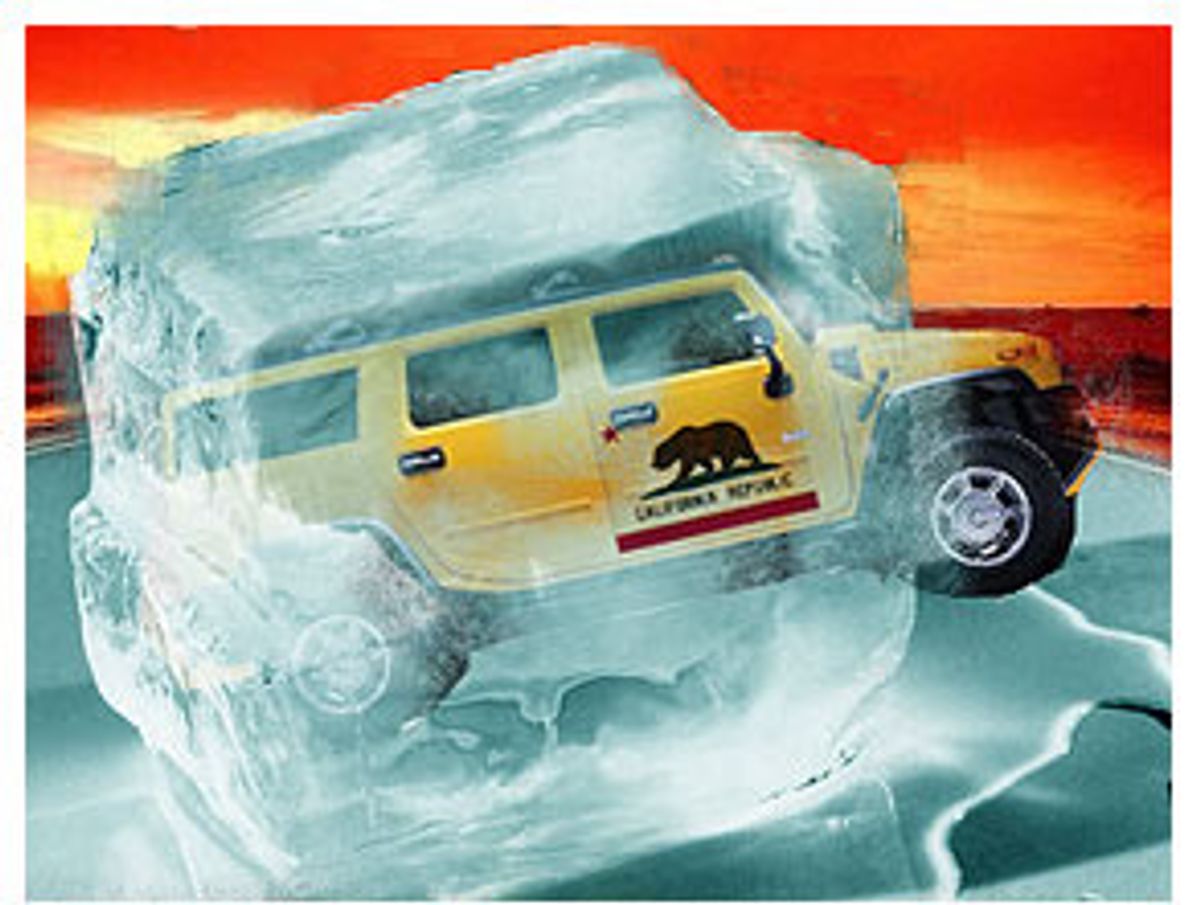

That's the message of the state's new proposed auto regulations, which would cut greenhouse gases emitted by passenger cars and trucks nearly 30 percent over the next decade. It's a message with bipartisan punch. The climate change plan, made available for public comment on June 14 by the Air Resources Board of the California Environmental Protection Agency, is the result of legislation signed into law by former Democratic Gov. Gray Davis in 2002. But the current Republican governor, Hummer-driving Arnold Schwarzenegger, has also pledged to uphold the new rules and defend them in any potential court battles.

The plan has outraged automakers and is setting up what could be another juicy showdown over the environment between the federal government and California. By going after carbon-dioxide emissions, which are considered by most climate scientists to be a major contributor to global warming, California is opening up a new front in the struggle over who controls fuel efficiency standards. Because unlike what are traditionally considered air pollutants, carbon-dioxide emissions, a byproduct of burning fossil fuel, cannot be filtered out at the tailpipe. To achieve the mandated reductions, the fleet of cars and trucks on the road in California must become fundamentally more fuel-efficient, burning less fuel per mile traveled.

Automakers are screaming because they say that by attempting to limit motor vehicle contributions to global warming, California is effectively regulating fuel economy. And that's supposed to be something only the federal government can do. (Although at the moment, the EPA seems more interested in making fun of drivers who want more fuel efficient cars than in actually increasing fuel economy.)

The fact that California can regulate air pollution from automobiles at all is a twist of regulatory history that dates back to California's horrendous smog problems in the 1960s. California began regulating the tailpipe well before the federal government got around to it in the Clean Air Act of 1970. When federal standards were finally set, California's laws were grandfathered in, and the state was allowed to continue to set its own standards. There's just one catch: As a result of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, the feds retained the right to set the CAFE standards -- or Corporate Average Fuel Economy -- the fuel-efficiency minimum levels which cars and trucks must meet.

California residents and legislators may see greenhouse gases as a pollutant requiring regulation, but the auto industry sees the rules as a sneaky backhanded way of cracking down on fuel economy, during a time when it is painfully obvious that the current administration has no desire to do so.

"States can't set their own fuel economy standards. Only the federal government can do that," says Eron Shosteck, director of communications for the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers.

Carmakers also contend that cutting back on carbon dioxide can't occur without significant, costly changes in how most cars are made today.

"Any scientist, physicist or auto engineer will tell you there is no way to control carbon dioxide at the tailpipe," says Shostek. "The only way to combust less fuel is to make cars lighter, smaller and less powerful, stripping them of features that consumers demand."

Does stopping global warming mean we all have to go back to driving Ford Pintos without air conditioning? Environmentalists and the state of California strenuously disagree -- most of the technological fixes necessary are already available. It's possible, they say, to have your DVD player and save the world at the same time.

California's climate-change plan enumerates various energy-saving technologies that could be used to create reductions in CO2 emissions, including everything from aerodynamic drag reduction to improved tires. The plan estimates that it will cost an average of $241 for a light passenger car and $326 for pickups and SUVs to meet the initial standards of 15 to 20 percent. But as the plan phases in, achieving greater reductions will get more costly, jumping to an average of $539 for light duty passenger cars and $851 for heavier vehicles.

Representatives of environmental groups stress that the changes will easily pay for themselves in just a few years through savings at the gas pump -- especially if fuel prices remain high. The Union of Concerned Scientists calculated that a 30 percent reduction of carbon dioxide emissions would improve fuel efficiency so much, that with gas prices at a meager $1.74 a gallon, it would take only three years to pay for the improvements. At last week's average California statewide price for regular gas, $2.26 a gallon, those costs would pay for themselves in about 2.3 years.

The auto industry disputes the figures. "It would add about $2,500 to $7,000 per vehicle," says Shosteck. "Eighty percent of the technologies that are mentioned in the Air Resources Board report are currently available on cars in dealer showrooms, but very few consumers choose those options because they are so expensive."

Jason Mark, the Clean Vehicles Program director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, says the auto industry has a long history of exaggerating the cost to consumers (and industry) of proposed regulations, whether they're seatbelts or airbags aimed at improving safety or catalytic converters that will cut pollution. Costs come down, he notes, when technologies are implemented widely.

"When Detroit sends its lawyers and lobbyists home, and puts its engineers to work, it's found that they can innovate all kinds of new solutions," adds Roland Hwang, senior analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

But Anthony Pratt, a senior manager at J.D. Power and Associates, an industry market research firm, echoes the auto industry's contention that most consumers won't voluntarily shell out up front in the car dealership for features that will improve the fuel efficiency of their new vehicle.

"Would someone be more likely to spend $700 to improve the fuel efficiency or do they want an entertainment center?" asks Pratt. "People start to think in those terms: 'That would be pretty cool, but I could use a DVD player every day.' People tend to favor the creature features."

Automakers aren't ready to file suit to stop California's plan yet, because the details of it won't be finalized for at least a year. But "we're examining all our options," says Shostek.

One of the reasons why Californian legislators have felt compelled to push for new regulations is the politically controversial side issue of whether carbon dioxide is really a pollutant at all. Under the Bush administration the Environmental Protection Agency has refused to regulate CO2 as a pollutant covered by the Clean Air Act.

It is true that CO2 occurs naturally, and events such as forest fires cause it to be released into the atmosphere. But most climatologists now believe that as humans rapidly burn fossil fuels for power the excess CO2 released into the atmosphere, along with methane, nitrous oxide and hydrofluorocarbons, is causing the planet to heat up, threatening human and environmental health. And when that happens, CO2 is acting as a pollutant, and thus can be legally classified as such, according to Dan Becker, Washington director of global warming issues for the Sierra Club.

"An air emission that causes or contributes to environmental or health problems is a pollutant," says Becker.

The American Lung Association of California agrees, arguing that global warming is a clear threat to the air quality in California, and therefore public health.

"There will be hotter days, so there will be more emissions from electricity generation, evaporation of fuel and power plant usage," says Bonnie Holmes-Gen, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association of California. "And increased temperatures will facilitate more ozone formation in urban areas that are already experiencing poor air quality."

Becker argues that California law can't be preempted by a federal standard, since there is, as yet, no such rule: "The reality is that this law doesn't regulate fuel economy. It sets a global warming emissions limit for automobiles, and the federal government has no law or rule setting a global warming limit from any product including automobiles. So, it can't be preempted."

Other environmentalists point out that California's existing auto regulations, such as its zero emissions vehicles program, have mandated the introduction of electric and hybrid cars. "It has a side impact on fuel economy. Some of the vehicles use no gasoline. Some use less gasoline, like a hybrid electric. That's not really a problem," says Hwang, from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Whatever happens with the law, the implications will reach far beyond California's borders. If New York, Massachusetts and five other New England states that have currently adopted or are in the processing of adopting California's existing tailpipe regulations also adopt the state's greenhouse gas emissions rules, then a quarter of the U.S. car market will be affected, says Jason Mark.

To put that in a global perspective, says Mark, if just the emissions generated by U.S. passenger vehicles today were counted as their own country, they'd be the fifth highest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, spewing more CO2 than all of Germany or India.

Shares