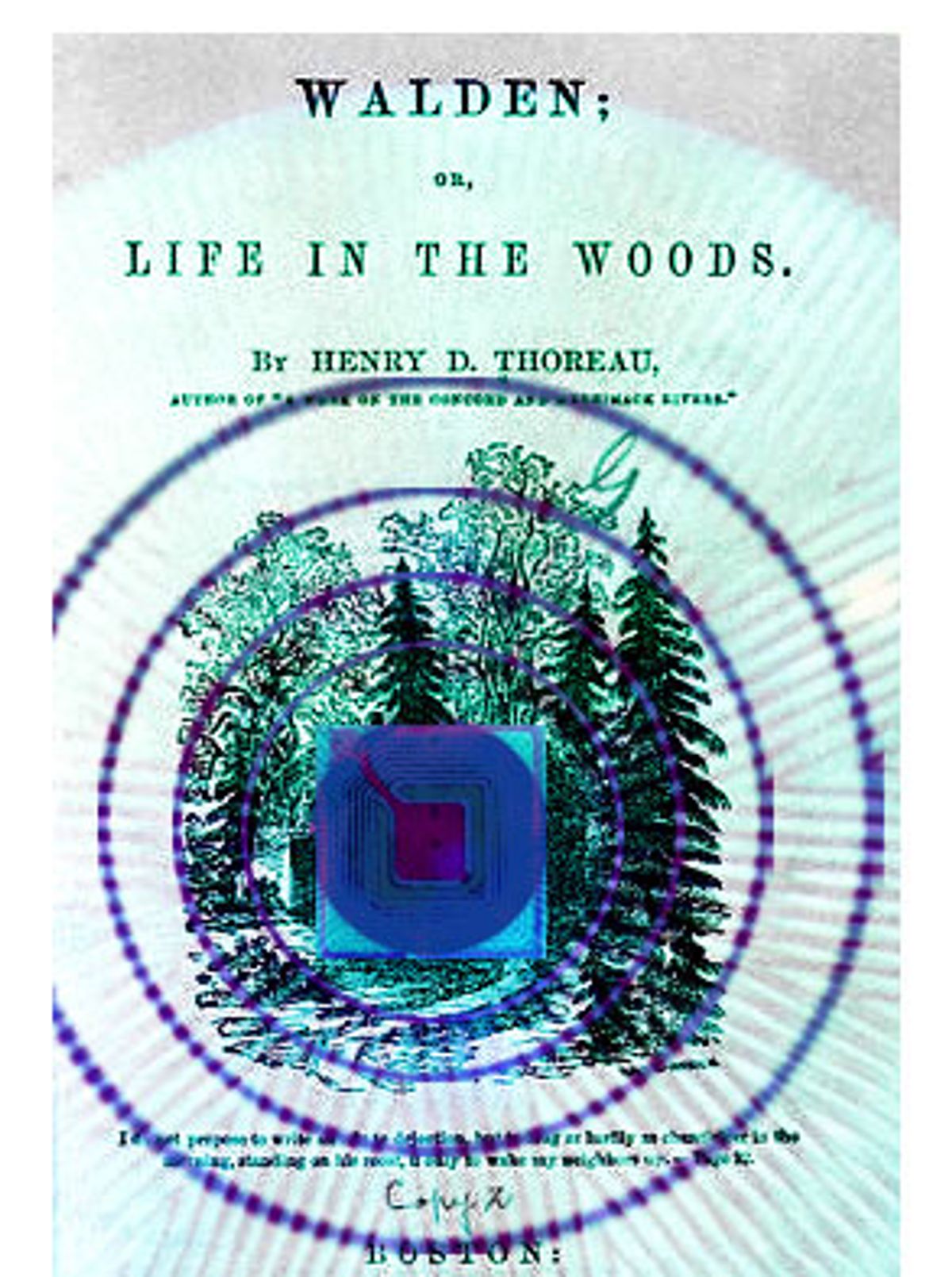

This week, staffers at the Berkeley Public Library will begin putting radio frequency identification (RFID) tags in half of the 500,000 items in their collection.

When the tags embedded in copies of "Gone With the Wind" and "Mein Kampf" pass within 18 inches of the library's RFID readers, they'll come to life, revealing a unique identification number specific to each individual copy. The tags will allow readers to do their own checkouts and will liberate librarians from the monotonous -- and sometimes painful -- task of endlessly scanning books.

By implementing the system this fall, the Berkeley Public Library will join more than 300 libraries around the world that have already outfitted their books with RFID tags, including the Santa Clara City Library, the Maricopa County Library in Arizona, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries, the Independence Township library in Michigan and the National University of Singapore Libraries. Even the Vatican Library's vast collection is getting chipped.

But by embracing RFID, librarians have raised the ire of civil libertarians who have long looked askance at the technology. They find it alarming that librarians, who are normally among society's staunchest defenders of intellectual freedom and First Amendment values, are contributing to the electronic erosion of privacy.

"Libraries are not Wal-Mart. Libraries have traditionally been very concerned about patron privacy," says Lee Tien, senior staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who has testified against the implementation of the tags at the San Francisco Public Library, which is in the early stages of adopting RFID.

The Berkeley Public Library sees compelling practical reasons for adopting RFID. Since the library expanded into a larger main building in April 2002, it has seen an increase in circulation without an increase in budget for more staff. The librarians think the new system will allow more patrons to check out items themselves without having to struggle with the library's clunky self-check bar code machines, freeing up staffers to help patrons better navigate the stacks. The librarians also hope that letting patrons check out their own books will cut down on the repetitive stress injuries, like carpal tunnel and shoulder pains, that plague many staffers.

"We had to get out of the checkout, check-in business," says Jackie Griffin, director of library services at Berkeley. "That's the place that staff was getting injured. And it's not helping people find materials in the library. We have really good, really well-trained people, and that's not using them in the best way." Facing almost $2 million in worker's comp costs every five years because of employees' repetitive stress injuries, the Checkpoint RFID system sounded like a relative bargain to Berkeley: $650,000 to tag the whole library, including the 500,000 tags, which go for 40 to 60 cents each. The main recurring cost is buying more tags as the collection grows.

But the specter of millions of books being tagged with unique identification numbers has raised a cloud of privacy concerns, sparking outcry from groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union. Are libraries putting at risk one of their most cherished values: protecting the rights of readers to peruse whatever they want without scrutiny?

Will anyone who happens to be carrying an RFID reader be able to figure out that you're toting around a copy of "Personal Bankruptcy for Dummies" in your $700 handbag? Or, even worse, will that RFID-chipped book in your backpack become a way to track your movements? Will a library book with its unique number in your bag suddenly become a way to track you? The librarians who are installing these systems say that they are taking precautions that make the first scenario highly unlikely. And they argue that the privacy gained through the ability to self-check out books without showing them to a library employee far outweighs the risks of the latter.

Many libraries, including Berkeley, are declining to put the name of the book or even the book's ISBN, its international standard book number, on the microchip implanted in it. They're using a unique bar code number instead, one that would have to be hacked out of a library's circulation database to connect it to a specific title. That's not just to assuage the privacy concerns of readers. For inventory management, libraries need to track individual copies of books and not the words between a given book's covers.

"Many libraries feel to protect patron privacy you should keep the information on the tag to a minimum," says Becky Anderson, a former librarian who is the marketing manager for 3M Library Systems, a company that has sold about 100 of the RFID systems currently operating in libraries around the world. "A publisher might put an ISBN number on a tag that they're selling to Wal-Mart, but a library wouldn't find that useful."

"The ISBN number is not terribly useful," agrees Gene Rollins, the assistant director for systems and technical services at the Harris County Public Library in Houston, Texas. Harris County has chipped all the video and audio cassettes in its collection and has plans to chip its 2 million books as the price of the tags continues to drop. The reason: All 150 copies of a popular title in stock at the library, like "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," have the same ISBN. "For us to be able to use this we need to track it down to the copy level. So, the ISBN number doesn't really get you anywhere," Rollins says.

But even if individual libraries, like Harris County or Berkeley, are careful not to put the title of the books on the chips, instead embedding each book with its own number -- a number not shared even with other libraries -- privacy advocates still have concerns. To them, opening the library up to RFID means opening it up to function creep. The numbers used aren't interoperable between libraries now, but does that mean they will never be?

Right now, retailers are using RFID only to manage relatively large shipments of goods moving through the supply chain. The cost of the chips still makes it prohibitive to enact the futuristic dream of wiring up everything from toothpaste to individual shaving cream bottles to every paperback book. But as the tags get cheaper, new books could arrive at the library with the ISBN already encoded in them by the publishing industry.

"Right now, those tags are about as meaningful as a bar code. You walk past a reader that picks up those tags, and it's just a jumble of numbers. But I am concerned that librarians are not thinking long term," says Beth Givens, the director of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, who herself is a former librarian. "What if the publishing industry adopts RFID and in doing so encodes the ISBN number. Now you've got a tag that is revealing meaningful information."

But librarians argue that there are very real privacy gains to be seen right now through RFID. Would you rather self-check "The Infertility Survival Handbook: Everything You Never Thought You'd Need to Know," or share your most intimate concerns with the librarian behind the checkout counter?

"When I was a teenager and I was figuring out that I was gay, I could not go to the library and check out a book about it, because some other human being was going to see that I was doing that," Griffin says. "And the same thing holds true for people who have medical conditions and people who have financial problems. For a certain portion of our population we've increased their privacy."

Griffin reports that since the library announced that it was planning to introduce RFID, the only concerns about the technology raised by patrons have been with regard to health issues: Would the antennae embedded in the book be emitting something that they'd rather not have coming their way? The librarians in Berkeley say that they haven't been able to find anything in the relevant literature that suggests so.

But the other privacy concerns that civil libertarians raise about the RFID tags are much harder to answer and somewhat more nebulous. While a privacy-conscious library like Berkeley can take steps to ensure that no one knows what you're reading, it can't get away from RFID's assignment of a remotely readable, trackable number to every patron walking out the door with a book.

"What we're talking about is real privacy pollution. They're polluting the social environment with the unnecessary ability for someone to be tracked," says Tien from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "The number is unique. And you don't necessarily have to know what it corresponds to. That allows the individuation of the person. They are not secure. And they are remotely readable."

How remotely is debatable, since librarians -- and manufacturers -- stress that the chips and readers are designed to interact only in a limited range, so you won't accidentally check out the books of the person in line behind you. But privacy advocates point out that the reader, not the chip, gives RFID its real power:

"Passive RFIDs are essentially like reflectors. They get their power from the reader. It emits a field. So it's from that field that the chip or tag gets the power," Tien says.

Privacy advocates paint a host of nefarious scenarios: How would you like to be unwittingly and remotely identified at a political rally, for instance, if not by name, then by the book in your backpack? If you're arrested hours later, would the book's RFID number be enough to prove you'd been active at the protest?

And one needn't hack into a library database to connect a specific number to a specific book. All you have to do is check out that book yourself and read the tag. So, if the FBI really wants to know who is reading "The Anarchist Cookbook" or the Koran, they need only check those books out of the library, check them back in, and then install a reader to capture that number on a street outside.

"You take the item out. You read the tag. And now you have a little database, capturing whenever someone else takes out this book," says Deirdre Mulligan, director of the Samuelson Law, Technology and Policy Clinic at UC-Berkeley's Boalt Law School, which worked with the Berkeley Public Library to develop its privacy guidelines around RFID.

But Mulligan doubts that a book in itself makes such a hot tracking device for monitoring political dissidents. The system just isn't very efficient -- people leave their library books at home or in their cars and give them to their kids. Still, she admits that the tags make surveillance via library books possible, if not probable: "It's not very likely, but there is always the outside chance."

Privacy advocates like the idea of tags that are rewritten with a new number every time a book is checked out. But, while technically possible, that's not what is going into the books on the shelves today.

Libraries aren't the only place that RFID is sparking privacy concerns. In California, a bill to set privacy standards for implementation of the technology in retail outlets recently failed in the state Assembly. Other states, such as Missouri and Utah have considered similar legislation.

But even people who have privacy concerns about RFID see why librarians want it. "It really does make inventory management wonderful," says Karen Schneider, director of the Librarians' Index to the Internet, who has written critically about RFID.

From the librarians' perspective, the promise of RFID in libraries does not stop at self-checkout. In theory, with a system that works smoothly, a librarian can just scan a wand up and down the stacks to see if all the books are in proper order, a laborious and time-consuming process to do manually. And librarians will be able to easily track which books in the noncirculating-reference rooms are being used and re-shelved frequently, so they'll know if it makes sense to invest in another Oxford English Dictionary or another subscription to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Schneider, who herself has been a librarian, found that in discussing the privacy issues in committee at the American Library Association, many large library directors got very defensive. "I feel like it's a battle I've lost," she says. "A number of large libraries implemented RFID before it really got on the privacy scope of anybody. By the time big well-heeled libraries had gone out on a limb to implement this expensive new technology, it was too late. They have a lot invested in no one saying: 'Oh, you know those 3 million books you just chipped? There's an issue with that.'"

Shares