Can you tell if someone’s lying? There are scientifically proven traits that most people exhibit when they’re cooking up a lie. Sweaty palms. Dry throat. Tight collar. Fidgety movements. Right-handed people tend to look up and to the left when thinking up a lie, and up and to the right when trying to recall a truth—the opposite for lefties. But can you tell if an object is lying? If it is not what it appears?

You sure can. Studying how forgers have successfully pulled the wool over our eyes offers some revealing clues as to how to avoid being fooled in the future.

There are some surprising characters in the pantheon of art forgers. Before he was a household name, Michelangelo began his career forging ancient Roman sculpture. He created a new sculpture out of marble, then intentionally broke it, buried it in a garden, and dug it up, declaring it to be a lost Roman antique. The cardinal who bought it grew suspicious after a few years, and demanded his money back from the dealer who had sold it to him. But the dealer was happy to accept because, by then, Michelangelo had made his famous Pieta and was the hottest new artist in Rome—the sculpture was sold on for a fortune, now as a Michelangelo original.

Many of the most famous forgers are more prankster than gangster: part illusionist, part admirable artist, part charming rogue, and all ingenious, often depicted by the media as harmless Robin Hood types, duping only wealthy and elitist individuals and institutions. They are often failed artists who turn to forgery to show up the art world that rejected their original creations and that they feel deserves to be shown up. Those who are caught, sometimes after decades of success, are found out through some accidentally inserted error or anachronism. Shaun Greenhalgh had a 17-year career as the most diverse forger in history, passing off everything from ancient Egyptian sculpture to 19th century watercolors. He was entirely self-taught, buying books from which he copied works and styles, and simply ordering materials off the Internet, while he turned his garden shed into his forgery studio. He was caught when, on what was supposed to be a 7th century BC Assyrian relief sculpture, he accidentally misspelled a word in cuneiform.

But not all anachronisms were accidental. Lothar Malskat forged medieval frescoes that he supposedly found during a church restoration. They were so admired that the German government ordered the printing of 4 million postage stamps featuring a detail from them. Such a success is a private one—only the forger himself knows the truth, and sometimes that’s not enough. Malskat wanted notoriety for having pulled off this fraud, but no one believed him, so he took the unusual step of suing himself, in order to have the public, official platform to explain that he really was the forger. He was disbelieved until he pointed out two “time bombs,” anachronisms in his work that he had intentionally inserted, just in case he was not believed. He had painted a turkey into the fresco—indigenous to North America, there were no turkeys clucking around medieval Germany. And he’d also inserted a portrait of Marlene Dietrich—who was definitely not clucking around medieval Germany.

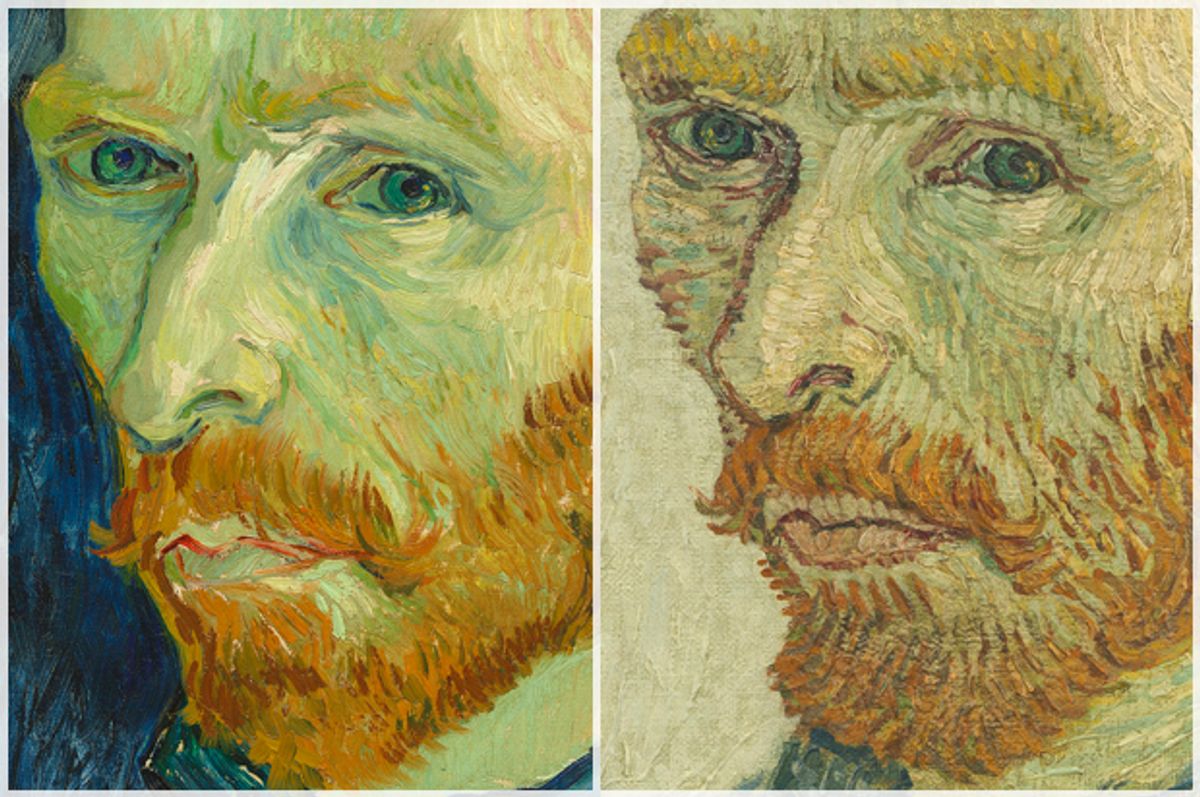

Time bombs can be visual, like Malskat’s magical medieval Marlene Dietrich, or material. Otto Wacker was brought to trial when the world’s two leading van Gogh experts couldn’t agree on the authenticity of several paintings he had sold. A Dutch chemist named Martin de Wild was called in to break the tie. In an episode from "CSI: Art Crime," he found pulverized lead and resin in the Wacker “van Goghs,” which would have been added to make the oil paint dry faster—something van Gogh never did. Wolfgang Beltracchi, who was recently released from prison, used titanium white in a forgery that was meant to have been made a decade before the pigment was developed. (One of his forgeries was eventually acquired by the actor Steve Martin.) The inclusion of a material that should not have existed when a work was supposedly made can give away the game, but requires testing. What fools the eye can rarely fool forensics.

But artwork is rarely subject to forensic tests. There is no good reason as to why this is—it’s a part of the sociologically bizarre organism called the art world. It is neither prohibitively expensive nor necessarily invasive to test the work. But the weird culture of the art trade revolves around gentleman’s agreements and a certain etiquette, and it’s just not the done thing, to rock the boat. If the artwork looks reasonably good, and, more important, if the story behind the work is convincing, then it is very unusual for it to be tested scientifically. The key to passing off forgeries is in the provenance, the documented history of the object: contracts, references to the work in archives, catalog entries, receipts and so on. If this is compelling, then most art dealers are satisfied and don’t feel the need to look deeper. After all, the dealer benefits only if the work in question is authentic (and was not stolen), so there is little incentive to look gift horses in the mouth. You might learn that you’re dealing with a forgery, or a stolen work, and not only lose your commission, and possibly lose face, but could also wind up in court. It’s easy enough for an expert to claim that they were fooled, as in the recent, high-profile case of Manhattan’s storied Knoedler Gallery, which sold forged works—the question was whether the gallery was tricked by a clever fraud scheme, or if it knowingly sold forgeries.

Art authenticity is all about perception. If the world thinks a work is authentic, then it is authentic. But forgers know that a convincing provenance is actually more important than an aesthetically perfect forgery or one that would fool forensic tests. Imagine a character who appears in a history book, but is actually an invention of the author, a personage nestled into real historical events. The more detail about the character’s biography, the more convincing the character. Provenance is the biography of an artwork, but provenance, like art, can be forged.

John Myatt’s paintings looked pretty good, but any expert worth his salt should have been able to see that they were painted with acrylic paints, when the original artists he aped, like Monet and Giacometti, would have used oils—but the “experts” never noticed, because the provenance was so convincing. But Myatt’s accomplice had made fake documents and inserted them into real archives, to be “discovered” by researchers, in order to prove the authenticity of Myatt’s forgeries.

"The Vinland Map," acquired by Yale University and purportedly the first map of North America, made in the 15th century, was found to have 20th century synthetic materials in its ink. But despite this fact, some scholars still think it’s authentic, because of the bizarre story of its arrival at Yale, gifted alongside an entirely authentic 15th century manuscript that seemed to have been cut out of the same book as the "Map."

The history of forgery is full of surprising stories and larger-than-life, ingenious characters, but it also provides real lessons in how famous forgers have succeeded—and how we can avoid being fooled in the future.

What can you keep an eye out for if you are buying art, whether you’re dropping seven figures or three, to help ensure that what you’re buying is genuine? Here are five tips to avoid being a forger’s next victim.

- Look at the back of paintings and the bottom of sculptures. There is often a wealth of information there, like old auction labels or owner stamps. Lazy forgers make the front of works look good, but might not bother with the parts that are not on view, so you may be able to identify something fishy going on by looking where the forger hopes you won’t.

- Ask for provenance documentation. This is a no-brainer and is actually required, in order to avoid potentially getting into legal trouble if a work you buy turns out to have been stolen: you need to be able to prove “due diligence,” that you checked to make sure the work was legal, and that you bought it in “good faith,” with the true belief that it was all above board.

- Double-check the provenance. Make sure that the provenance really does go with the object in question (and was not borrowed from some other object, in an art version of Don Draper), and that it was not forged. Be suspicious of provenance that is impossible to confirm with a phone call (if all the galleries listed as having displayed the work in the past are out of business, for instance, this might be a reason to probe further).

- Buy from reputable dealers with a good track record. Famous dealers and auction houses get fooled, of course, but they are much more likely to deal in authentic works. Buying online especially is asking for trouble—if you can’t see a work in person, look a dealer in the eye and ask questions, then…good luck.

- Request forensic test results, or the option to have a work tested yourself. This is not the least bit standard in the art trade, but it should be. If a dealer refuses, be prepared to walk away. Would you buy a car that a dealer refused to allow your mechanic to look over? Artworks often cost much more than a car, but we still tend to buy them based on the opinion of experts, who may have ulterior motives, or may be less “expert” than they claim.

Shares