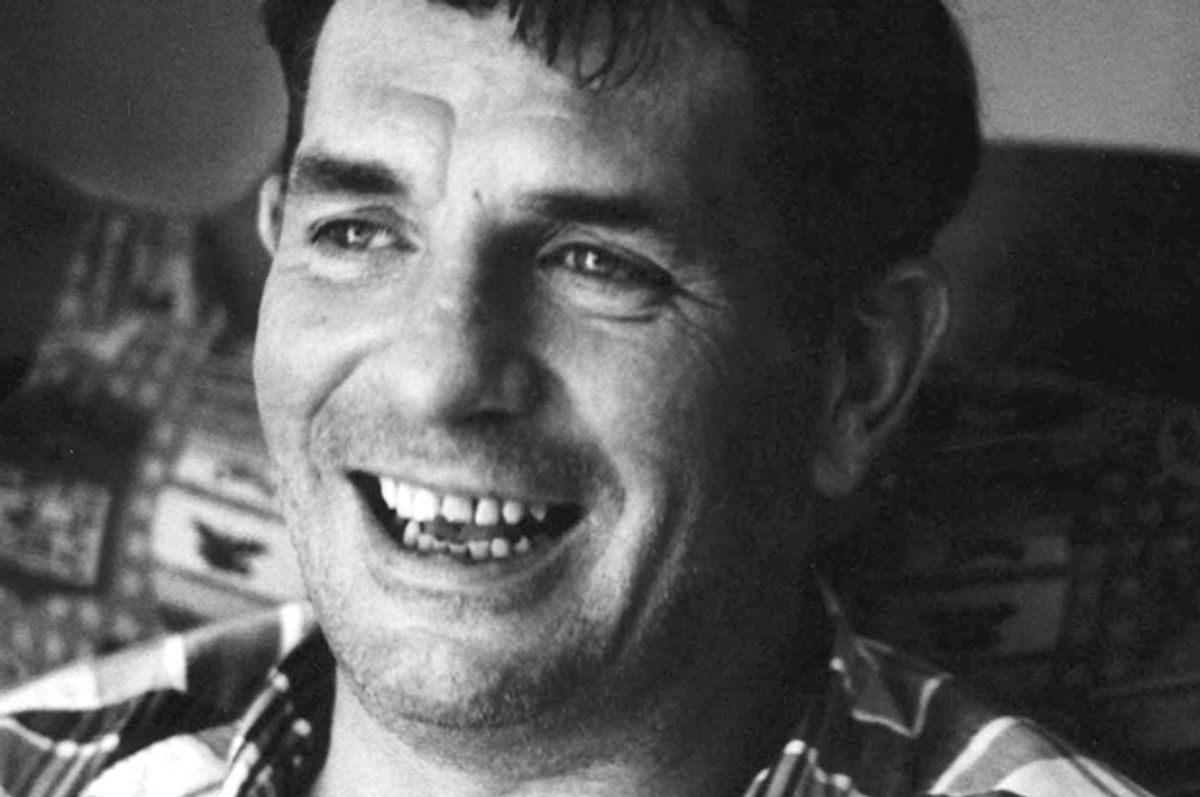

THE EDIFICE OF Columbia University’s Butler Library still had the glimmer of freshly quarried limestone in the early 1940s, when Jack Kerouac traipsed around the Manhattan campus with his pals.

THE EDIFICE OF Columbia University’s Butler Library still had the glimmer of freshly quarried limestone in the early 1940s, when Jack Kerouac traipsed around the Manhattan campus with his pals.

Kerouac could not have missed the building’s symbolism.

A monument to manliness, Butler’s façade touts the names of more than 40 thinkers, writers, and politicians – all of them men.

Ionic columns draw the eyes up stone shafts toward an all-male marquee: Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Virgil. Ten more European names grace the building’s sides – Shakespeare, Dante, Chaucer, and the like. Two dozen American statesmen and author-men – Lincoln, Thoreau, Poe, and more — are lionized in smaller print on the front.

It seems appropriate that this vast book sarcophagus houses some of Kerouac’s letters.

~

I am quite familiar with this piece of architecture. In the 1990s, I had a view of Butler from my faculty office at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. One day, I was sitting at my desk speaking with Beth Reinhard, a spirited student who now covers politics for the Wall Street Journal.

Her gaze gravitated toward the library.

“For god’s sakes,” she suddenly said, “they couldn’t come up with a single woman?”

Apparently not.

A donation from Edward Harkness, scion of a Standard Oil stock millionaire, was used to build the $4 million library in the early ‘30s, during the crux of the Great Depression.

But the building really is Nicholas Murray Butler’s big erection.

The names branded into the stone were personally selected by Butler, Columbia’s president for most of the first half of the 20th Century. Although largely forgotten now, he was viewed as a sage in his time. The New York Times, in particular, blew Butler’s trumpet, describing him in a 1927 editorial as “the incarnation of the international mind.”

Count me among his detractors.

An arriviste who grew up in the gritty factory town of Paterson, New Jersey, Butler put on a phony posh British accent—and, occasionally, a toga—and exhausted audiences bloviating about whatever he pleased. He published turgid letters in theTimes about a breathtakingly tedious panoply of subjects—Hawaiian statehood, local government reform, Prohibition, world peace, and more.

In the spring of 1945, during the closing months of Butler’s long Columbia tenure, a whippersnapper student used his finger to scrawl imprudent messages into the accumulated grime of his dorm room window, which faced Butler Library.

Among them was this one: “Nicholas Murray Butler Has No Balls.” He added a childish sketch of a penis and testicles.

The student was Allen Ginsberg, who would gain fame as a Beat poet. Ginsberg said he wasn’t upset with Butler; he was simply trying to prompt someone to clean his damned window. He got the cleaning, though it was a Pyrrhic victory: He was suspended from school.

~

A story about the Beats drew me back to Columbia a few years ago, 15 years after I left the J-School. (Old-fashioned journalism looked more and more like a craft entering its denouement. I feared I was funneling students down a career gangplank, so I returned to writing, where any occupational failings were mine alone.)

On a spring day in 2012, I visited Columbia’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library on Butler’s sixth floor to conduct research about a murder case, the bread-and-butter of my work as a writer. The Times had asked me to look back at the 1944 slaying of David Kammerer by Lucien Carr, the precocious Columbian who gave intellectual inspiration to the coterie of dissent-minded young men who become the core of the Beats.

I had learned that Butler holds a boxed collection of 37 letters written to Carr by Ginsberg between 1956 and 1975. The same box hold 23 letters and postcards from Kerouac to Carr, written from the mid-‘50s to 1967, two years before Kerouac drank himself to death, at age 47. (Carr, who died in 2005, bequeathed the letters to Columbia.)

A number of the Ginsberg letters were lyrical travelogues sent from exotic places. Kerouac’s letters were something else—jocular, raw and breezy, one hail fellow to another. But the letters had one thing in common: Well into adulthood, both Ginsberg and Kerouac clearly continued to beg for Carr’s esteem.

As a long day of research and reporting wound down, I quickly thumbed through the Ginsberg letters, each in its own sequentially-numbered file. I then turned to the Kerouac letters. The last of five letters he wrote to Carr in 1962 stopped me cold.

It was typed and two pages long, dated Aug. 11, 1962. (Actually, Kerouac wrote the date in French: “aout 11.”) The letter is a make-believe Q&A between Kerouac and “the renowned French Journalist Lucien Tablet Carr.” (In fact, Carr was an editor with United Press International in New York.) After a nitpick about UPI, Kerouac got to the meat of his message:

LUCIEN: Mr. Kerouac, what do you think of Marilyn Monroe? Your honest opinion.

KEROUAC: She was fucked to death.

LUCIEN: Will you send us a telegram saying so?

Six days before the date on the letter, Monroe, 36, had been found dead of a barbiturate overdose at her home in Los Angeles. Her death was both a spectacle and a singular American tragedy. My mouth went agape as I sat reading the letter. How could Kerouac be so pitiless?

In 1962, he was 40 years old and far removed from the callow youth of his Columbia days. What would prompt a worldly, middle-aged man to emote such adolescent contempt for a woman whose life and death had been heartbreaking?

Aristotle, one of Nick Butler’s darlings, might have lectured Kerouac about pathos. He likely would have failed to move his emotional needle. After all, Kerouac has emerged as a prototype of the mid-century modern misogynist.

Kerouac’s "On the Road" generally treats women as cardboard cutouts with vaginas. The point of view of male characters is not merely a gaze; it is a drooling leer. Women are limned based upon a handful of hollow adjectives. (“Beautiful” is the author’s go-to descriptor.) They are inventoried by breast size and hair tint, like sex bots.

Lee Ann is “a fetching hunk, a honey-colored creature.” There is “a beautiful blonde called Babe – a tennis-playing, surf-riding doll of the west.” And then there is Terry, “the cutest little Mexican girl… Her breasts stuck out straight and true; her little flanks looked delicious; her hair was long and lustrous black; and her eyes were great big blue things with timidities inside.”

There are many similar examples, including this snippet of dizzying dialogue by Dean Moriarty, a character based on Kerouac’s buddy Neal Cassady:

“Oh I love, love, love women! I think women are wonderful! I love women!” He spat out the window; he groaned; he clutched his head. Great beads of sweat fell from his forehead from pure excitement and exhaustion.”

Self-regarding the Beats may have been. Self-aware they were not.

~

I ordered a photocopy of Kerouac’s Marilyn Monroe letter during my visit to Butler and have kept it at hand ever since.

I can’t let it go.

Academicians and amateur enthusiasts have cranked out scores of books on Kerouac and the other Beats, parsing and parrying over every detail of their work and their lives. I’m certain that other researchers have found and read Kerouac’s appalling letter about Monroe, but I have been unable to find a single published reference to it.

That surprises me since this overlooked document seems to add an important piece of evidence of Kerouac’s infantilism when it comes to women—and, more broadly, a distillation of American male misogyny, circa 1962.

It was too puerile for publication, you argue? Have you read Bukowski?

I sat in the library that afternoon wondering over Kerouac’s point.

Clearly, the letter was a plea for Lucien Carr’s elusive endorsement via humor rooted in shared chauvinism. Affirmation from Carr was the sine qua non of Kerouac’s manhood.

Though he was among the youngest in Columbia’s Beat clique, Carr was cornerstone. The others were entranced by his profane rants about the beauty of unalloyed creativity and the plague of cultural philistines.

Ginsberg called the boyishly handsome Carr his first love. And in one of Kerouac’s lesser romans-à-clef, he described the Carr character as “the kind of boy literary fags write sonnets to, which start out, ‘O raven-haired Grecian lad…’”

And then there was David Kammerer. He had stalked Carr to New York (and several other cities) from their hometown of St. Louis, where Kammerer had once been his Boy Scout leader. Thirteen years older, Kammerer sexually abused Carr, beginning in his adolescence.

Kammerer was a familiar figure in the Beat circle, and the others were fully aware of his obsession with Carr. James W. Grauerholz, a Beat biographer, has described Kammerer as Carr’s “stalker and plaything, his creator and destroyer.”

At 3 a.m. on Aug. 14, 1944, Carr and Kammerer walked down the hill from Morningside Heights to Riverside Park after drinking at the West End saloon, a Columbia hangout. Seated on a slope in the park, Kammerer made “an offensive proposal,” as the Times put it. Carr fatally stabbed him with a Boy Scout knife and rolled his body into the Hudson River. The New York Daily News called it an “honor killing.”

Carr surrendered to authorities the next day, after rambling around Manhattan with Kerouac. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and served a short term at the Elmira, N.Y., state reformatory.

By literary osmosis, the killing gave credibility to the tortured-soul narratives in the three Beat masterworks: On the Road, Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems, and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch. One critic suggested they felt “a narcissistic pride in having been tangentially involved in anything so Dostoevskyan.”

~

Rebranded as Lou, Lucien Carr began a 47-year career at UPI straight out of the reformatory in 1946. He came to be regarded as a great editor and generous mentor to young journalists. (Until he sobered up, he was also a legendary drunk.) A history of UPI calls Carr “the soul” of the news service, the same role he played for the emerging Beats.

Though beloved as a newsman, Carr apparently was deeply flawed as a father and husband. His son Caleb Carr, the writer, has said that Lucien abused his family physically and psychologically. Caleb Carr linked the “cycle of abuse” to the sexual and psychological damage inflicted by Kammerer on young Lucien. Caleb Carr wrote, “Of all the terrible things that Kammerer did, perhaps the worst was to teach him…that the most fundamental way to form bonds was through abuse.”

Lucien Carr had been at UPI 15 years when he received the Marilyn Monroe letter from Kerouac. Like the dedicated phallocentric that he was, Kerouac worked in a riff about giant penises:

LUCIEN: ….Say, wattayamean she was fucked to death?

KEROUAC: It was what was told me about another girl in San Francisco, who jumped off a roof, that she was fucked to death. I understand Joe DiMaggio had a dong actually as long as a baseball bat…and that Arthur Miller had a dong as long as Robert Sherwood.

In the mid-50s, Monroe spent nine tempestuous, abusive months married to DiMaggio, the baseball star, followed closely by a turbulent marriage to Miller, the playwright. And Robert Sherwood? He was a 6-foot-8 writer from the Algonquin Round Table gang, New York literary luminaries a generation older than the Beats. So, yes, a big old Sherwood might have been a killer-sized penis, especially to the chronically insecure (and 5-foot-8) Kerouac.

He continued his letter to Carr by suggesting that he was just the man to protect Monroe from those giant phalluses.

KEROUAC: Sir, I would have given her love.

LUCIEN: How?

KEROUAC: By telling her that she was an Angel of Light and that (writer/director) Clifford Odets and (acting coach Lee) Strasberg and all the others were the Angels of Darkness and to stay away from them and come with me to a quiet valley in the Yuma desert, to grow old together like “an old stone man and an old stone woman”…to tell her she really, is really, Marylou.

“Marylou” refers to another character in On the Road, a “beautiful little chick” based on Luanne Henderson, Neal Cassady’s real-life adolescent bride. Kerouac wrote, “Marylou was a pretty blonde…But, outside of being a sweet little girl, she was awfully dumb and capable of doing horrible things.” It seems absurd that Kerouac conflated or equated Monroe, one of the most powerful women in Hollywood, with Cassady’s child-wife, who was fifteen when they married. But it’s also a telling detail that Kerouac imagined – saw himself as – Monroe’s protector, her superhero.

Later in the letter, Kerouac refers a second time to Angels of Darkness, presumably the 1954 potboiler film about Roman prostitutes (“LOVE WAS THEIR TRADE! Daughters of Joy…Sisters in Sin!”). After a few inside jokes and another homoerotic reference to someone who might “suck your spire up,” Kerouac turned to the deaths of two other famous actresses.

LUCIEN: Mr. Kerouac, now that our altercations are begun, and I am a journaliste, what do you think caused the death of Carol Lombard then?

KEROUAC: Imploding eyeballs.

LUCIEN: And of Jean Harlow?

KEROUAC: What YOU said: parrot cement.

~

I can’t decode the references to eyeballs and parrots, but I do recognize Kerouac’s obsession with blonde actresses who died young. Freud could have spent years unpacking the psyche behind that fixation.

Note that Lombard had died a full 20 years before, in 1942, at age 34. And Harlow died at age 26 in 1937, when Kerouac was 15 years old. For Kerouac, one hot blonde screen star apparently blurred with the next into some warped apotheosis of Woman as a loveless cipher. They stand forever apart from him, on the other side of a screen. Yet Kerouac yearns for them, like a schoolboy at a matinee.

Kerouac ended his make-believe Q&A with one tender note—not about dead blonde actresses, but about Carr:

LUCIEN: What is your opinion of ME?

KEROUAC: I just thought about you with tears, here in old Orlando, cause it’s been a long time.

That might seem sweet—had it not been buried in woman-hating sludge about death-inducing penal assaults. (We have attached a copy to this story so readers can examine the letter themselves.)

So how should we judge this latest affirmation of the writer’s troubling misogyny?

Kerouac’s misogyny already has inspired a cottage industry of commentary. One contemporary writer calls the Beats “immature dicks.” Another suggests it is unrealistic to consider Kerouac (or any writer) outside the context of his or her times.

So Kerouac was “of his time,” to use a tired phrase. And some use the same excuse for the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1962, the inaugural edition of Ms. Magazine was still a decade away. But Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was in the publishing pipeline that year, and the English-language edition of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex had been available since 1953.

On the Road was published in 1957, just five years before Kerouac wrote the fucked-to-death letter to Carr. After the glamour of his first novel faded, Kerouac spent the 1960s on a bender. Chronically drunk, desperate for money and living with his mother, he peddled the same repackaged book content into the twilight of his life.

His 1968 book, Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46, was built from the same bricks, mortar and misogyny as On the Road. His editor, Ellis Amburn, later said, “I had so wanted to love the book, but the final manuscript was full of gratuitous racial and sexist slurs, and Kerouac’s contract protected him from editorial changes.”

~

Columbia’s rare book library was wrapping up business for the day; my time with the original copies of Kerouac’s letters was drawing to a close. Around me, other patrons rushed to view a few final pages as Columbia staff members tidied up, warning of impending closure.

This corner of Butler’s sixth floor has changed since Kerouac’s time on campus, and the valuable documents maintained here are kept secure behind glass doors and a phalanx of earnest librarians.

No doubt Kerouac spent his share of time at Butler too. As I repacked the letter files into the Lucien Carr box, I wondered what he might have to say if he found his Monroe letter, all these years along.

Would he cringe? Argue that it was a joke? Own it? Burn it?

A bonfire would be needed to incinerate all the sexist passages in Kerouac’s oeuvre, of course. Yet On the Road remains relentlessly popular, now nearly 60 years since its publication. The book shows up on English lit reading lists and tucked in backpacks beside Rough Guides. Jack Kerouac continues to enjoy a reputation—deserved or not—as a literary contrarian who was willing to raise an extended middle finger toward American society.

Surely, few read Kerouac today without some degree of awareness of his misogyny problem. Perhaps contemporary readers use a single squinting eye to scuttle past the objectionable passages.

Kerouac’s Monroe letter must be regarded as exceptionally repulsive. And the passage of time adds context that makes its content even more significant. Marilyn Monroe has advanced in stature from a sex symbol to a cultural icon to an influential proto-feminist figure. She has transcended mere sexuality—for those able to see beyond her exterior.

Kerouac apparently could not. Poignantly enough, his On the Road was among the books in the Monroe’s library when she died.

She apparently admired him. And he objectified her.

So after three years of mulling Kerouac’s letter, it is with an owly gaze that I have come to regard this author of the great dissident cultural marker of the American mid-century.

The former callow youth, a high school gridiron golden boy long removed from his glory days, rolls rickety into middle age, sleeping down the hall from his mother. Behind the bedroom door, he is alone with his woody, lost in a wet dream about the iconic blonde he is certain he ought to possess.

In fact, Jack, you don’t deserve her—never did, never will.

Shares