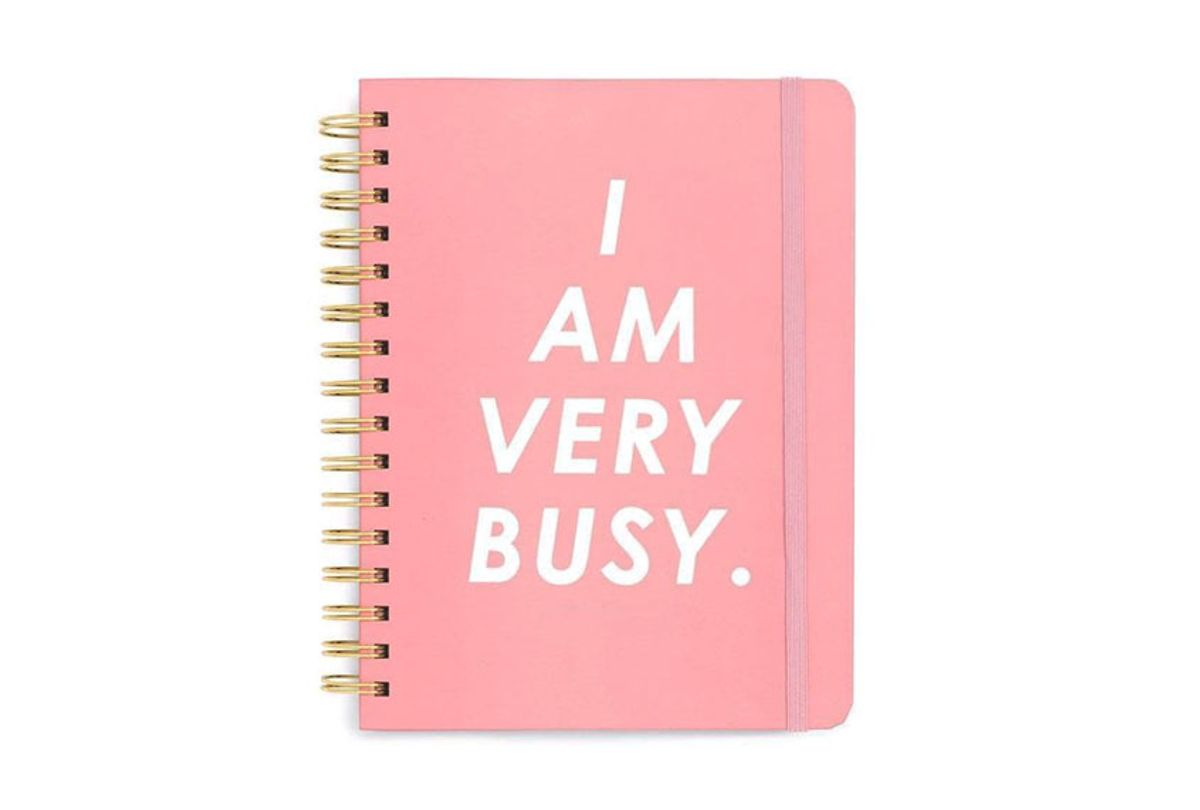

Few people embody the pastels-and-typography aesthetic of our era as perfectly as Jen Gotch. I first discovered her nearly a decade ago, via her captivating photography and the addictively popular retail brand she cofounded, ban.do. You know that thing on Instagram, where you see a picture of a woman sporting a pink planner that says "I Am Very Busy"? That's ban.do — cheerful, colorful and cute, but with a strong dose of hustle.

That identity also applies very much to Gotch, a sunny blonde who runs, as the Daily Dot has described it, "an empire built on rainbows." Yet over the past few years, Gotch has also built an equally formidable present as an outspoken mental health advocate, openly chronicling her own experiences with bipolar disorder on her social media and via her podcast, "Jen Gotch is Ok . . . Sometimes." Now she is the author of a brand new memoir, "The Upside of Being Down, How Mental Health Struggles Led to My Greatest Successes in Work and Life." I spoke to her recently on "Salon Talks" via Zoom — even sheltering in place, she's still flawlessly fashionable — about the book and why toilets are great idea incubators.

Watch my "Salon Talks" episode with Jen Gotch here or read a Q&A of our conversation below.

What was it, after everything that you've done, every direction you've gone in, that made you say now was the time that you wanted it to tell your story in this particular format? You've been telling it for years.

People started approaching me probably five, six years ago to write a book. I had always wanted to write one. I first wanted to just write a straight business book, which I tried to do about six years ago with a friend. We didn't get very far because I was very heavily involved in the day-to-day for ban.do.

So it stuck as this dream in the back of my mind, and then Lauren Spiegel, my editor, probably started reaching out five years ago. Every year or so she would pop back in, "Are you ready? Are you ready?"

The last time she did, a couple of years ago, I felt like I was finally in a place logistically to be able to do it. It wasn't that it was all of a sudden like, "I'm ready to tell my story and I'm ready to write about it." I feel like I had been marinating on that for a long time. I just was subconsciously aware that it was going to take a lot more brain space than I had, when I was so immersed in the day-to-day of ban.do. We were finally at a place where I could float away for whatever time was needed to do that.

She [Spiegel] was very passionate about it being a memoir. I really wanted to write just a straight-up self-help book. I'm probably more didactic in nature than I am a narrative writer, but she's an editor for a great reason. She really has a good sense of how things should go. It felt like the natural progression, especially after the podcast, and seeing what a connection I could make through that, to be able to give people something that they could have forever, and revisit in a way that maybe is a little bit easier to digest than the way I talk sometimes.

I'm really a huge believer in timing and I still believe, even given the current circumstances, that everything happened exactly as it should.

One of the things that is really important in your story, and in particular in this book, is your process of diagnosis and medication. I think a lot of us don't know, when we're at the beginning of feeling not right in the head, what is going to be involved. For you, it took years and years and years. Yet when you finally got to that place where everything came together, it was not a devastating thing to get a diagnosis. It was actually a relief.

It, of all of the many diagnoses that I have received, always felt like a relief. For whatever reason, I just didn't view it as a stigma. I know that I'm probably in the minority. Hopefully that percentage is starting to flip.

Because of that, it was just a diagnosis like anything else. When you don't feel well and you go to the doctor and they say, "This is what you have," you immediately feel relief because you're like, "Okay, now I know what it is I'm working with and I can work towards feeling better." That is always what a diagnosis meant to me. I already knew there was something wrong, so it wasn't a shock, "Oh my gosh, something's going on."

I knew something was wrong. I needed someone to say, "This is what it is." I'm a hugely curious person, so to be able to have language around something and be able to research it, and learn about it, and learn about myself in the context of that diagnosis was incredibly helpful for me.

You have been part of this wider conversation over the last decade or so about mental illness. It's not just you. Shows like "Crazy Ex-Girlfriend" and celebrities coming forward and talking about their mental health issues. It is becoming de-stigmatized, but it is also becoming de-stigmatized first for only certain kinds of people. And we still see so many taboos when it comes to mental illness for men, and for people who are in other socioeconomic populations. As one of the people who was a part of that first wave, what do you think we can all be doing to bring other people into that conversation?

I also think the other thing is that culturally it tends to be very different, too. From my end, it's just continuing to talk about it. I think the beauty of people who have a platform and an audience is to show that it's not a debilitating thing. It doesn't have to mean that if you have a mental health issue, you can't succeed or live the great life. That's a big part of removing the stigma. As far as how we get through to those other areas, what has been the most impactful is, we work with a nonprofit called Bring Change To Mind.

The necklaces that we created, the net proceeds go to Bring Change To Mind, and they're an organization that's basically built to de-stigmatize mental health.

I worked specifically with their student division, and in speaking to like 300 students at their high school student summit last year, of different races, different religions, different socioeconomic groups. These kids are so eager to talk about it, and that feels to me where the hope is. These 14-, 15-year-olds, their ability to talk about their issues, the things that they were saying to me, a total stranger, in front of everybody else, just blew me away. I'm like, "That's actually the generation that's going to do it." It's certainly going to take time. Even where I sit, there's still a lot of stigma. I'm sort of insulated because everyone knows my deal and I have a world built around me because of that.

But I think empowering these younger generations to not ever feel that, that's when it's going to happen. I was like, "Do I just move into their high school? What do I do? This is so amazing." Empowering children is where I see the straightest line. I would imagine in everyone you speak to there are different ways, which is amazing. We're going to have to come at it from a lot of different angles. But that's a huge focus for me.

It's not just mental health struggles that particularly younger people are dealing with, it's also career and academic. You talk about your process of, in your early years, going through having different careers, trying out different jobs, trying what works and what doesn't work. There's so much pressure on everybody right now to pick a lane, stay in it and be perfect at it right out of the gate. That's also a common American success story. "I built this thing in my garage when I was in high school and now I'm a cool rich guy."

Certainly there were a lot of objectives I had in writing the book, and changing the narrative around success was certainly one of them. I didn't think I was succeeding unless I was following this straight path to a goal that I had decided I had when I was 18. I'm still deciding that, and I'm 48. So I've been very passionate about sharing that, to say, "I didn't know what I was doing."

Somehow it all ended up leading to this amazing career, but at the time I felt incredibly lost. But I was following my intuition and my passions, and there's something to be said for that. I think there's so much about success that we get wrong.

In speaking to these kids, I saw a lot of that too. Whether it's the perfection, or the busy-ness, The amount of extracurricular activities that they're expected to have, and the homework, and then to get As, get first place. I think that's something that needs to be debunked as well. I feel like we're all in this forced introspection right now, so some of that maybe is going to move along a little bit faster. But I agree, as successful adults, we have to show that it's not always as it looks, being busy all the time is not healthy and there is no such thing as perfect. So let's show that over and over again and make it okay.

It's really great for those of us who follow you, getting to that part of the book where the woman who defines "I am very busy" — you've made that a brand — gets to a point of saying, I need to maybe learn a lesson about that, too. You take a page from the people who are maybe not putting their identity on busy-ness. We are in that place now, where as you say, we're all trying to figure out how to be maybe a little less busy.

Among all of the horrible things that are happening, there's the potential for some really amazing things to happen, because things are standing still in a way that they never could have. I know for me, when things have stood still in my life, I've been able to really get deep into things, and get clear about what's important and what isn't. I think as a world, to be able to do that together, maybe we're going to make some progress.

It's like when you talk about getting all those great ideas on the toilet. We all need to be on the virtual toilet, and have that stillness.

Let's be on our toilets.

You talk early in the book about the idea of bringing emotion into the workplace. More than ever, we're all emotional. Our workplace is our home, and our home is our workplace. You can't compartmentalize anymore, it's impossible. How have you dealt with that historically, and how are you dealing with it now? How do you do that in a way is also ethical, that respects your own boundaries, and respects those of your colleagues? Because everyone else has different ideas of how vulnerable they want to be in their professional lives.

Ban.do was sort of born out of emotions; it's never been this corporate entity. The DNA of our company has always been that there are going to be emotions. I'm obviously an emotional person, except for the times in my career where I was really struggling personally. I feel like I'm quite a responsible manager of emotions, which is another reason why I feel like I should lead that for people, because I understand where those boundaries lie, emotion-wise.

I think the thing that happens in the workplace when we talk about emotions is, we're just assuming that means someone walking around crying all the time. But emotions are not just crying. It's joy and fear, and sorrow and gratitude. I think that allowing the full spectrum is important because of the amount of time that we're at our jobs. To think that as humans we're going to be able to put that in our drawer when we get to work, and then collect it with our things at the end of the day, just isn't possible.

You're stifling people, and eventually that causes other problems.The question really is, how do we define what is responsible? That's going to be hard to have this blanket statement [about]. I feel it is a huge responsibility on the leadership of the company to decide what that is, exemplify that and create a safe space for the employees to follow suit, while also feeling comfortable enough for them to say, "This isn't right. I need more, I need less." It really depends on communication, because you have to create a safe space. When I talk to people who feel right now they don't have that safe space, and wouldn't even know where to begin to have any emotion at work, it's because they're scared to lose their jobs.

It's really important that the leaders own that. Now, there's a huge challenge. Because we're not together, we can do as many Zoom calls as we want, or encourage people to call and talk, but people are really going inside themselves in a way that they're able to, because everyone is secluded.

I'm actually not sure what the answer is. I was literally writing notes this morning on, how am I going to try and make it safe emotionally? Because the other thing, liability-wise, it's very confusing. Now as every company is trying to find their footing and figure out what it's going to look like, there are a lot of technicalities to what you should say and what you shouldn't say.

With emotions, mental health and workplace — on top of all of the humanness — then there is the business piece, the policy piece. I certainly haven't figured out the cyber version of emotions in the workplace, but I just always try to go back to all the things I know about being human, when I have felt the safest, and advocate for that. Being the chief creative officer and the founder allows me to lead with a little bit more emotion than probably an accountant at an accounting firm might be expected to.

You leave the book on this note about the practice of optimism. There is often a misperception that optimism, as you say, that it's something that we come by natively. Some of us have more of an optimistic or resilient bent than others, but it's like anything else, and it has to be worked at and practiced and applied. So particularly now, what are you doing to further your practice of optimism, that maybe I can learn something from, Jen?

It's something I have practiced for a long time. I think that one of the big keys is understanding that I'm really talking about realistic optimism. I'm not talking about, "Isn't this wonderful?" I think there's a huge part of acknowledging how horrible any situation is, or disheartening, or whatever. Right now we're dealing with a horrible situation, so I'll just talk about that. It's not pretending it's not there. It's understanding it and trying to be realistic about what that means, and then tempering your optimism accordingly. Find a silver lining, or an upside, in any situation. Sometimes it takes a long time for it to present itself. I believe they are always there. Optimism, especially as you're training, has a lot to do with creating new neural pathways in your brain. If you tend to go to a darker place, you have to kind of make new pathways.

So for me, the first thing you have to do is get some of that negativity out of the way. Something that I learned over the last couple of years was understanding the relationship we have with our thoughts, and how we actually don't have to believe everything that's generated up there. A lot of it is generated by an ancient mechanism that used to help us when we had to fear for our lives every day. Now it's just looking for a job and it tends to take us on these journeys of fear, and worry, and projected outcomes that may never come to fruition. We spend a lot of mental energy going there. To me the best thing you can do is just start to recognize when that is happening and try not to have a reaction immediately. You start by putting some distance there, and then once you've got some distance, you can start to observe them and you can let a bunch of them pass by without any reaction.

Then, as you really start to create that space, you can start to insert something about optimism, something about gratitude, and just start to reframe your thinking. That is literally what I did over the last few years, as I tried to eradicate my own anxiety that was getting so debilitating that I was just like, "I'm not going to be able to write this book, or go outside, or have relationships." That is what I did, and now it's a lot quieter up here. There's not a lot of that chatter about how horrible things are, or what if this happens, or what if that happens? I absolutely know that all of these horrible things can happen, but I choose to focus my energy either in silencing it with mindfulness and meditation, or just trying to evoke joy within myself.

That sounds like that's a lot, which I get. But I think the key is operating from a place of gratitude and just taking inventory of what's going on up there, and just starting. Start there.

Shares