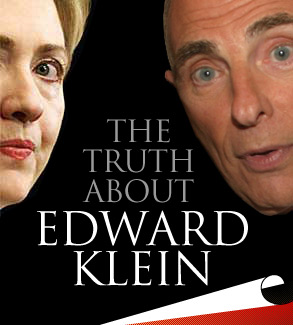

“I’m not being used by anybody,” said Edward Klein, author of the book “The Truth About Hillary: What She Knew, When She Knew It, and How Far She’ll Go to Become President,” published today by Sentinel, a conservative imprint of publishing behemoth Penguin Group. Klein was responding to a question about whether the right wing was using his past work at supposedly liberal institutions like the New York Times and Newsweek to lend authority to his book’s assertions about Hillary Clinton, which many are calling shoddily reported and nastily personal.

“I worked for the organizations that I worked for and people can make of that whatever they want,” Klein continued evenly. “But it’s absurd to suggest that anybody has put me up to this.” He went on, with a touch of amusement, “It’s that people are confused. They don’t know what to make of me. Because what is somebody with my background and reputation doing writing a book like this? Why aren’t I writing a book supporting Hillary?”

OK, we’ll bite: What is a guy with Klein’s background and reputation doing writing a book like this? “The Truth About Hillary” boasts a passel of petty, sexist and plain old “no duh” claims against Hillary: “She shows no wifely instincts,” “She isn’t maternal,” “She’s a feminist, but she rode to power on her husband’s coattails,” “She has abetted decades of chronic infidelity,” “Many of her closest friends and aides were lesbians.” It claims to shed light on the way that “the culture of lesbianism at Wellesley College shaped Hillary’s politics” and that “she set up an elaborate system to monitor her husband’s girlfriends.” The book opens with a scene in which former White House intern Monica Lewinsky fondles Bill Clinton’s penis at Radio City Music Hall.

“Life of Samuel Johnson” it ain’t. But the fear of many Democrats is that “The Truth About Hillary” could prove to be a powerful weapon against Clinton as she moves closer to becoming the Democratic candidate for president in 2008. Even if most of the claims in “The Truth About Hillary” turn out to be baseless, there’s a palpable fear that it could be a lethal cousin to 2004’s campaign killer “Unfit for Command: Swift Boat Veterans Speak Out Against John Kerry.” In New York media circles, the discomfort is doubled by the knowledge that this time, the cudgel is being wielded not by some easily dismissed nut-job from a state they fly over, but by a man they know, they’ve worked with, and whom they may have even created.

If his enemies were writing “The Truth About Edward Klein,” we’d learn that the author and editor is an odd duck. While some former colleagues had terrific things to say about Klein, many were eager to turn their backs — or their hoses — on him. (Some of the same people who excoriate Klein for using off-the-record information in his Clinton book declined to attach their own names to the comments they made for this story.) Klein’s detractors — happy to hypothesize — have cooked up several nasty theories about his move from legitimate journalism to increasingly cheesy tabloid tell-alls. One goes that he was never actually a media insider, never liked, and never accepted by New York’s media hierarchy. (The not-so-subtle implication being that a book like this is an attempt to break the toys and smash the idols of the playground clique that left him out.) Another insists it’s an obsession with powerful women and a desire to destroy them that drives Klein. And, of course, there’s a theory that insatiable greed has led him to do anything for a buck.

But all of these narratives rely on a plot that’s been somewhat revised with hindsight. The truth is, Klein was something of a macher himself. He didn’t just work at the New York Times Magazine, he was its editor from 1977 to 1988, a position that did not exactly send him to journalism Siberia. Under his stewardship, the magazine won its first Pulitzer Prize. He also went to work for Tina Brown at the ultimate in-club, Vanity Fair, in the early 1990s; he remains a contributing editor there today. “The Truth About Hillary” was excerpted in this month’s issue, right next to the bombshell story unveiling the identity of Deep Throat. As for how chilly, preening, ambitious, misogynistic or greedy the guy is: Those qualities don’t exactly set him apart from a lot of other guys running around the New York Times or Condé Nast buildings at this very moment.

In a world in which our careers and the states we live in can serve as accurate predictors for how we’ll cast a ballot, how the hell did Edward Klein evolve, or devolve, depending on your perspective, into Judas Iscariot of the New York press?

The answer to the question “Why did you write this book?” is, according to Klein, “pretty simple.” “I write about fascinating people. Hillary Clinton is probably the most fascinating person in the country today, if not in the whole world,” he said. He decided to do the book in late 2002. “I knew I wanted it to be a hard-hitting, truth-seeking book, and though I did not go in with any ax to grind or any agenda, I knew it was going to be warts and all, because that’s what I write.”

Klein sold “The Truth About Hillary” to Penguin in 2003 along with “Farewell, Jackie,” his fourth book about the Kennedys, as a two-book deal. Klein will not disclose how much he was paid. Viking, Penguin’s prestigious trade imprint, published “Farewell, Jackie”; the Clinton book went to the brand-new conservative imprint, Sentinel. Sentinel’s publisher, Adrian Zackheim, said that Klein’s Clinton proposal had been “about the aptness of a book about her, not about what was going to be in it.” It wasn’t just aptness; it was angle. As Zackheim said, “We don’t anticipate selling to people who are advocates of the senator.”

According to this timeline, Klein did the bulk of the research and writing of “The Truth About Hillary” while being paid by an openly conservative press that was not looking for a book that would appeal to Clintonites. When asked if the circumstances could have had an impact on his objectivity, he said no. “I wrote this book for Sentinel exactly the way I would have written it had it been for Random House or Simon & Schuster,” he said. “However, I don’t think any of those imprints would have published it.” Claiming that “book publishing is probably more liberal in its political affinities than even newspapers and magazines,” Klein said that “the people at the top of Penguin aren’t happy with ‘The Truth About Hillary.’ I think most people who work at that conglomerate hope to see Hillary as president of United States.”

Klein does not. “I think she’s the closest thing we have today to what I would call a Nixonian character,” he said of Clinton. “Like Nixon, she is paranoid; she has an enemy list. Like Nixon, she has used FBI files against enemies. Like Nixon, Hillary believes the ends justify the means, and like Nixon, she has a penchant for doing illegal things.” When asked to elaborate on the illegal things, Klein laughed. “I believe that the order to get those FBI files came directly from Hillary to Craig Livingstone,” he said. “I believe that the miraculous discovery of the Rose law firm billing files two days after the statute of limitations ran out was also an illegal act. I think she lied to the country when she said that this Monica Lewinsky matter came as an utter and complete surprise to her.”

But lying about Lewinsky was not illegal. “Well, technically it’s not,” replied Klein. “But it certainly strikes me as, if not illegal, then at least immoral.”

Clinton’s press secretary, Philippe Reines, offered only this response to the book, “We don’t comment on works of fiction, let alone a book full of blatant and vicious fabrications contrived by someone who writes trash for cash.”

Klein pointed out he’s been a journalist for almost 50 years now. For “The Truth About Hillary,” he said he interviewed over 100 sources, including classmates, White House support staff, speechwriters, military aides, Cabinet officials, senators and congressmen.

The trouble is, so much of his information is attributed to others who have written on the Clintons that his own sources, anonymous or not, don’t exactly burn the barn down. While there is lots of ugliness about Clinton’s role in Whitewater and the Lewinsky affair, none of it will come as news to anyone who has watched television over the past 14 years. Klein’s fresh revelations include the accusation, made by a fired White House usher, that Clinton went over budget in her White House redecoration and “secretly tapped into Historical Association funds.” Klein doesn’t indicate in his text that he checked this claim with the people who manage the Historical Association budget. But even if he had, the great faux-wicker scandal of ’93 is not likely to provoke the frothing fury of, say, allegations that John Kerry shot himself to get a Purple Heart.

But rumors that Hillary Clinton is secretly a lesbian very well could. It’s true, Klein doesn’t come out and directly level this charge, but the intimation is there. In advance of the book’s publication, even Page Six in the New York Post — not exactly the press organ of choice for Hillary supporters — questioned the veracity of Klein’s reporting on the issue, and took issue with the book’s innuendo about Clinton’s proclivities, including the implication that because Clinton is friendly with lesbians, she may well be one herself. “The reason the words ‘lesbian’ and ‘lesbianism’ appear in the book at all have nothing to do with sex and all to do with politics,” said Klein in defense of the book. “Hillary’s politics were shaped by the culture of radical feminism and lesbianism at Wellesley College in the 1960s.”

Here Klein seemed to go off the deep end, rolling off names of Clinton friends and appointees and their Culture of Lesbianism crimes: Tara O’Toole (Marxist reading circle), Roberta Achtenberg (persecuted the Boy Scouts), Joycelyn Elders, Donna Shalala, Janet Reno, Eleanor Acheson. “She surrounded herself with many women who were either openly lesbian or suspected of being lesbian or appear to be masculine,” he said.

“I did not invent the fascination with her sexuality,” said Klein. “When people found out I was writing this book the first question they asked me was: Is she a lesbian? Should I have written a book that didn’t address that question? What kind of woman would countenance a marriage of 30-something-odd years in which her husband is constantly betraying her? Does sex mean anything to her? What kind of woman boasts that one of her favorite publications of all time was a magazine called Motive, published by the Methodist Church, in which Marxism, feminism and lesbianism were promoted as positive ideals for young people? What kind of woman is purposefully surrounding herself as a public figure with women known to be lesbians?”

It seemed that the expected answer could only be: “A lesbian?”

No, insisted Klein, for what could only be legal reasons at this point. “If she had had lesbian affairs, don’t you think the right-wingers would have uncovered at least one lover?”

As for comparisons between his book and “Unfit for Command,” Klein said that he wrote his tome “to take a good, hard look at Hillary’s true character. If my book is being compared to the Swift Boat Vets’ book on that account, then comparison is apt.” (Klein has not read “Unfit for Command.”) “On the other hand, I did not set out to scuttle Hillary’s chances of becoming president.” In fact, said Klein, he believes that Clinton “not only has a great chance of getting the Democratic nomination in 2008, but a great chance of winning the White House.” Klein said he is registered as an independent and votes “rarely” to preserve his journalistic distance.

Klein was born in 1936 in Yonkers, N.Y., and at the age of 21 secured a job as copy boy at the New York Daily News. “I fell in love with journalism,” he said, “practically the moment I set foot in the city room.” With a degree from Columbia’s School for General Studies and a fellowship from its journalism graduate school, Klein spent three years in Japan, reporting for United Press International and other papers. He also developed an early devotion to the work of A.M. Rosenthal, then a New York Times foreign correspondent, who later helped him get his first big break as a foreign affairs writer at Newsweek, where he eventually became foreign editor.

Ed Kosner, former editor of Newsweek and the New York Daily News, arrived at Newsweek as a national affairs writer at about the time Klein started there. The two climbed the masthead together, and when reached by phone, Kosner said that Klein and Newsweek were a good match. “Ed was a very enterprising and very talented newsmagazine writer and editor,” said Kosner. He recalled Klein as “a work chum” who has always been “a very serious man; he’s hardworking and he’s very focused.” Kosner didn’t remember Klein showing any signs of political partisanship back at Newsweek. “I don’t think Ed is an extremely political guy,” said Kosner.

In 1977, Klein got a call from his mentor Rosenthal, then managing editor of the New York Times, asking him to take over the paper’s weekly magazine. Klein recommended a complete overhaul, and set about making the magazine more fun. He published shorter articles, hired fashion writer Carrie Donovan, amped up the magazine’s home design section, and made photography a priority. Proud of his “nose for news,” Klein also bragged about the articles he assigned on subjects like the revolution in in vitro fertilization. “I have often been criticized for not assigning serious articles,” Klein said, “but the magazine in some ways became more serious.”

Not everyone was thrilled.

Klein admitted that he came to the job with some “very, very severe weaknesses.” The first, he said, was that he was used to exercising magazine-style editorial control over copy, which didn’t go over well at the Times. The second, he said, was that he “had an overbearing personality [that] did not really fit well there.” Third, Klein said, was the prevalence of Times lifers who couldn’t care less who the new guy was. “These were people who were virtually impossible to fire unless they stole money or plagiarized,” said Klein. “And the attitude was, ‘Look buddy, I’ve been through three editors and I’ll go through three more after you’re gone,’ which didn’t please me very much. So I had this recalcitrant staff used to doing things the way they’d been done since Lester Markel founded the place.

“I’m not trying to compare myself to Tina Brown,” said Klein, “but just the way she found the New Yorker a hard nut to crack after it had been run virtually the same way for decades, I found the Times Magazine staff and its methods a tough nut to crack. And nuts I cracked. So I admit it made me not the most popular guy in the world.”

“He was a snapper, an angry guy,” said one of his former colleagues who asked not to be named. Longtime Times correspondent Steven Weisman remembered, “When he first came aboard I shared some of the skepticism felt by my colleagues.” Weisman, then a White House correspondent, recalled, “The first time I met with Ed he lectured me — and I remember this quite well — he implied that a lot of what I wrote about was boring. He might have even said that outright.” Weisman continued, “But he ended up getting good work out of me.” In fact, Weisman said that he feels that he did the best work of his career for Klein. “It was his sense of narrative,” said Weisman. “He wanted good stories.” About Klein’s work now, Weisman said, “I am amused and delighted that he’s found these outlets for his creativity.”

Some perceived Klein’s popularity problem as extending outside the workplace, and told tales of his tone-deaf attempts to mimic the social cues of Manhattan’s movers. “He had this need to be accepted that never happened, either at the Times or in any real publishing circles,” said one person who knew Klein then. “There was this desire to be let in in a way that never happened, and that led him to be obsessed with powerful people and want to strike at them.” Klein dismissed this characterization: “Anyone who is editor in chief of the New York Times Magazine is automatically invited to everything. In no sense was I shut out of New York City or its social circles. I was a first-nighter on Broadway. I was at parties with Frank Sinatra. I had to turn down more things than I went to.”

But as far as the Times went, Klein agreed with his detractors. “Obviously I was an outsider,” he said. “I think I was insensitive and I wish I hadn’t been.” But, he said, his unpopularity didn’t faze him. “It didn’t bother me because during the entire period I was there I was under Abe’s protection,” said Klein. “You needed a rabbi at the Times and you could not get a stronger rabbi than Abe Rosenthal.”

It didn’t hurt that the magazine was improving. There was the magazine’s first Pulitzer Prize, in 1983, won by Nan Robertson for her story on toxic shock syndrome, which Klein described as “great, a vindication that we were doing the right thing.” He also noted that when he started, the magazine had been losing money. “When I left in the end of ’87 it was grossing almost $130 million a year and adding $20 million of that after expenses to the bottom line of the New York Times,” Klein said.

There was a dark spot, though, a journalism hoax that embarrassed Klein in 1982, when reporter Christopher Jones did a piece for the magazine on the Khmer Rouge in which he claimed to have seen Pol Pot through binoculars on a distant hillside, his eyes “dead and stony.” Alexander Cockburn, then at the Village Voice, smelled something fishy. Noting that Jones “clearly has an uncanny knack of being in the right place at the right time,” Cockburn wrote a column remarking on the similarities between Jones’ piece and a passage from Andre Malraux’s accounts of his travels in Cambodia. The Washington Post picked up on Cockburn’s column and ran a story questioning the piece. After a confrontation with Klein and two other Times correspondents, Jones confessed to having invented the story.

In the lead-up to “The Truth About Hillary,” some Clinton defenders have implied a connection between the Khmer Rouge story and Klein’s departure from the Times, but Klein remained at the paper for five years after the hoax. However, when Max Frankel succeeded Rosenthal as executive editor of the New York Times in 1986, Klein said he figured his goose was cooked. Frankel kept him on for a year, until, after a disagreement about a Constitution bicentennial cover story — Klein wanted original art by Robert Rauschenberg and a novella by James Michener; Frankel wanted articles by legal scholars — Klein resigned. “If I hadn’t resigned I probably would have been forced out,” said Klein. “It just wasn’t working.”

After the Times, Klein considered launching his own magazine, but the stock market crashed. He returned to reporting, writing a story for Clay Felker’s Manhattan Inc. about Arthur Sulzberger Jr.’s succession to the top of the Times. The piece was spotted by old eagle-eye herself, Tina Brown, then the highflying savior of once-moribund Vanity Fair. She took Klein to lunch at the Four Seasons. “She asked me what I’d like to do and I told her I’d love to do a story about Emperor Hirohito,” said Klein. “She said, ‘Fine, go ahead and do it.'” Klein did the story, and was soon made a contributing editor at the magazine. In an e-mail, Brown wrote, “I had a great time with Ed at Vanity Fair. He always had fabulous story ideas and had this self-regenerating energy where he would make all his own action.”

About this time, Klein was asked by Parade editor Walter Anderson to take over the “Personality Parade” column famously penned by Lloyd Shearer for many years. Klein has been writing the column — one of the most widely read weekly columns in the country — ever since. By the early 1990s, Klein was officially starting to color outside of journalism’s etiquette lines, beginning with a story he wrote in 1989 about former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. The two had met a decade earlier, when Klein published a novel, “Parachutists,” with Doubleday, where Kennedy was an editor. They’d struck up a professional friendship and occasionally met for drinks. “I’m not saying I’m the only one who ever hit it off with her,” Klein said defensively, conscious perhaps of suggestions that he cannibalized his relationship with Kennedy for what would become four books on her and her family. It began, though, with a Vanity Fair cover story on the occasion of her 60th birthday, with which Kennedy did not cooperate. Klein said when he told Kennedy he was writing the piece, “She was not pleased and our relationship cooled,” adding, “It wasn’t as though I was stealing secrets she had told me and telling the world.” Later, Klein claimed, their phone calls resumed, and Kennedy never brought up the story.

After her death, Klein published “All Too Human: The Love Story of Jack and Jackie Kennedy” with Pocket Books. It didn’t make the family happy, but Publishers Weekly was impressed by Klein’s 200 attributed sources. “What he has come up with can surely be regarded … as thoroughly vouched for,” read the review. (“The Truth About Hillary” footnotes just 26 original attributed interviews.) “All Too Human” shot high on the bestseller list and showed Klein that he’d tapped a lucrative vein. “The success of ‘All Too Human’ made me realize I’d only written about half her life,” he said. Next came “Just Jackie: Her Private Years,” which also sold well. Klein said he “probably wouldn’t have done any more Kennedy books except that when John Jr. died in that plane crash … I started to think to myself, why would one family be subject to so many tragedies?”

The resulting tome, “The Kennedy Curse,” was the book that started to get Klein in real trouble with the legitimate press, filled as it was with lurid details of John Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette’s troubled marriage. While interviewing Klein about “The Kennedy Curse” on CBS’s “Early Show,” host Harry Smith confronted Klein right out of the box, listing the accusations in the book and telling Klein, “When we spoke with another Kennedy biographer, Laurence Leamer, he said none of these things rang true to him … Respond to that.” Smith also said of the book, “It has a kind of a breathless sort of tabloid style to it … the style of it almost made me question the validity of it.” Nevertheless, the book was a bestseller, and Klein defended it. “I was severely criticized for making this stuff up, for exaggerating, for using anonymous sources,” said Klein. He theorized that people were too heavily invested in the myth of the glossy Kennedy-Bessette union to hear anything negative about it. “I can understand that,” said Klein, “but everything I wrote about them later turned out to be confirmed by other writers and is now accepted as true, and nobody has ever said, ‘Sorry we were so critical, because you turned out to be right.'” When asked how it felt to take a beating from his peers, Klein replied, “How could it feel good? It was sort of stunning and surprising, because I had been treated so well up to that point.”

Like “The Kennedy Curse,” “The Truth About Hillary” relies heavily on anonymous sourcing, and has already drawn criticism for it. This drives Klein crazy. “Why don’t people feel that way about Bob Woodward’s books in which he doesn’t even have any footnotes?” he asked. “I’m not knocking Woodward, but why did Ben Bradlee go with Woodward and Bernstein? Yes, I rely on anonymous sources and I’ll tell you why. You cannot write about Hillary Rodham Clinton unless you’re willing to let people [speak anonymously]. They’re afraid the Clintons will wreak their vengeance on them and they have good reason to believe this.”

More than one source mentioned Klein’s fascination — or obsession — with powerful women, women like Kennedy and Clinton. Is it possible that he had an urge to turn the tables on powerful females, to destroy or dominate or consume them? Klein laughed. “My wife is a strong woman. My mother was a strong woman. I like strong women … Fascinated, yes; obsessed, no.” As for destroying them, Klein said, “I am not threatened by strong women, believe me. That’s a piece of intellectual gibberish.”

Klein also offered up complicated explanations of how the rest of the early leaks from the book have been misread or misunderstood. He claimed that the Bill-raped-Hillary-to-get-Chelsea scandal fluffed by Matt Drudge last week, was taken out of context; the drunken Clinton was just making a joke about how his wife was frigid. And he stood by his reporting on late Sen. Patrick Moynihan’s wife Liz’s dislike of Clinton, despite accusations from Moynihan’s daughter Maura that he misquoted her mother.

The Moynihan chapter was excerpted in Vanity Fair, and Wayne Lawson, who has edited Klein since he started at the magazine, also backed up Klein, pointing out that “unlike book publishing, everything that we print is very carefully fact-checked and legally vetted.” Lawson, who has edited pieces by Klein on Wen Ho Lee and Etan Patz, described his writer as “incredibly professional, a very solid reporter who always comes in with lots and lots and lots of notes meticulously presented.”

“I love being a reporter,” Klein told me over the phone. “That is the most fun thing in life.”

Maybe. But another fun thing is making money. As Klein’s old Newsweek boss Ed Kosner said when I’d asked if Klein had been an outsider with his nose to the window, “Oh, I don’t think that he burned with a lust to be any kind of a journalistic insider. Sometimes people like to make a living, right?”

So maybe all the pop-psych explanations of how Ed Klein became Ed Klein pale in the light of an old-fashioned desire to get rich. After all, Klein’s arc teaches us that it’s not impossible for a foreign correspondent to become a retailer of Bill Clinton’s tasteless rape jokes. A guy who once steered a Pulitzer Prize-winning weekly magazine can go on to “report” that Hillary Clinton’s ass broadened after having Chelsea due to “chronic lymphedema … [a] disorder that causes gross swelling in the legs and feet.” He can also write a passage this vapid, about Clinton’s Wellesley classmates: They “refused to wear pretty dresses, style their hair, use coy remarks, or deploy any of the trappings that might make them appear subordinate to men. As a result, they sometimes appeared mannish.”

The day before its publication, “The Truth About Hillary” was No. 9 on Amazon’s list of bestsellers. And having a book in that slot is an ambition familiar to any New Yorker who has ever climbed a masthead or lunched at the Four Seasons.

“Isn’t it Dr. Johnson who said any writer who doesn’t write for money is a fool?” said Klein. “What I do for a living is write popular nonfiction and the more popular it is the more books I sell and the more money I make.”