Stanley Tookie Williams was executed by lethal injection at California's San Quentin prison early Tuesday morning. He was 51 years old.

Williams walked into the execution chamber, a semioctagonal room with a padded green gurney and flooded with pale white light. He lay down. Guards strapped him in. A guard kept a hand on Williams' shoulder. A nurse had difficulty finding a vein in his left arm. She accidentally drew blood. It took 12 minutes to prepare the IVs. Williams held his head up. He looked at the press -- 17 journalists in all. He looked at his loved ones -- five of them present -- and mouthed words that journalists couldn't hear or understand.

At 12:21 a.m., the first drug, five grams of sodium pentothal to make Williams unconscious, was pumped into his arm. That was soon followed by injections of 50 cc's of pancuronium bromide to stop his breathing and 50 cc's of potassium chloride to stop his heart. After a few minutes, Williams' stomach begin to spasm and contract. Soon he was not moving. The roomful of witnesses sat in silence looking at Williams' unmoving body.

A circular flap in a heavy metal door near Williams' body was opened by someone unseen. A piece of paper was slipped through and was unrolled by a female guard who made the final announcement. Stanley Tookie Williams was dead at 12:35 a.m. Three of his passionate supporters, including Barbara Becnel, a former Los Angeles Times reporter, cried out, "The state of California just killed an innocent man."

Inside San Quentin's media center, journalists finally sprung into action. Most had been here over four hours. The décor was like that of an old library, with drab purple carpeting and bright halogen lighting. A trophy case stood next to instructional videos on what to do if taken hostage. A stage with a folding table and the American flag was at the front of the room. "It looks like they do plays here," one journalist had said earlier. "They could put on 'Annie.'"

For most of the night, there had been apprehension and boredom. One guy sketched in a notebook. "Monday Night Football" played on a small TV. Others flipped through the press package prepared by the San Quentin press office. It opened with three pages of pictures of a young Albert Owens, followed by pictures of his dead body, lying in a pool of blood next to empty Pepsi bottles. On another page that addressed Williams' Nobel Prize nomination, the booklet explained that over 140 nominations are submitted each year and that former nominees have included Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini.

But now journalists clutched their BlackBerrys, hoping to get the first e-mail from their colleague who witnessed the execution. They began tapping the heels of their polished shoes. A photographer took a picture of their faces lit up by their hand-held devices' blue glow. A TV cameraman walked up and started filming.

When word broke out of the official time of death, a journalist got on his cell, "Hey, Joe, it's me. It's 12:35!" People ran to their camera stations.

People standing outside said prayers. They sang "We Shall Overcome," although a girl sitting on top of a trailer said, "I don't believe that. I'm not singin'." A Richmond, Calif., reverend began shouting through a megaphone: "I'm tired of singin'! I'm tired of talkin'! Do somethin'! Let's do somethin'!" He marched out to a chorus of amens, hollering and people following him. It was as if everyone decided to leave and follow the one person who was angry and ready for action.

A Native American man on the other side of the street held a large upside-down American flag with a white swastika painted in the blue field of stars. He was shouting at the "white maggots" who had defiled his land, who had oppressed and enslaved his people. He yelled at the blond news anchors below him, "You're all immigrants. This is my land you've been poisoning for the last 500 years." He lighted the flag on fire as a black woman told him he shouldn't do that, that he should have more pride in this nation. He responded that it was time for a "true indigenous people's revolution." Then the white picket fence he was holding onto broke and he fell down the small embankment. Then the people he'd been arguing with lifted him up and asked him if he was OK. "Yeah," he said. "I'm OK."

Williams' last chance had been clemency. But early in the afternoon on Monday, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger had made his decision. Williams had never apologized nor showed remorse for his victims, the governor's statement said, so there could be no clemency.

Williams had been convicted of murdering four people. He was found guilty of shooting Albert Owens during a 7-Eleven store robbery on Feb. 27, 1979, and shooting Yen-I Yang and Tsai-Shai Yang and their daughter, Yee-Chen Lin, 12 days later at a Los Angeles motel the family owned. He was sentenced to death in 1981. He maintained his innocence until the end.

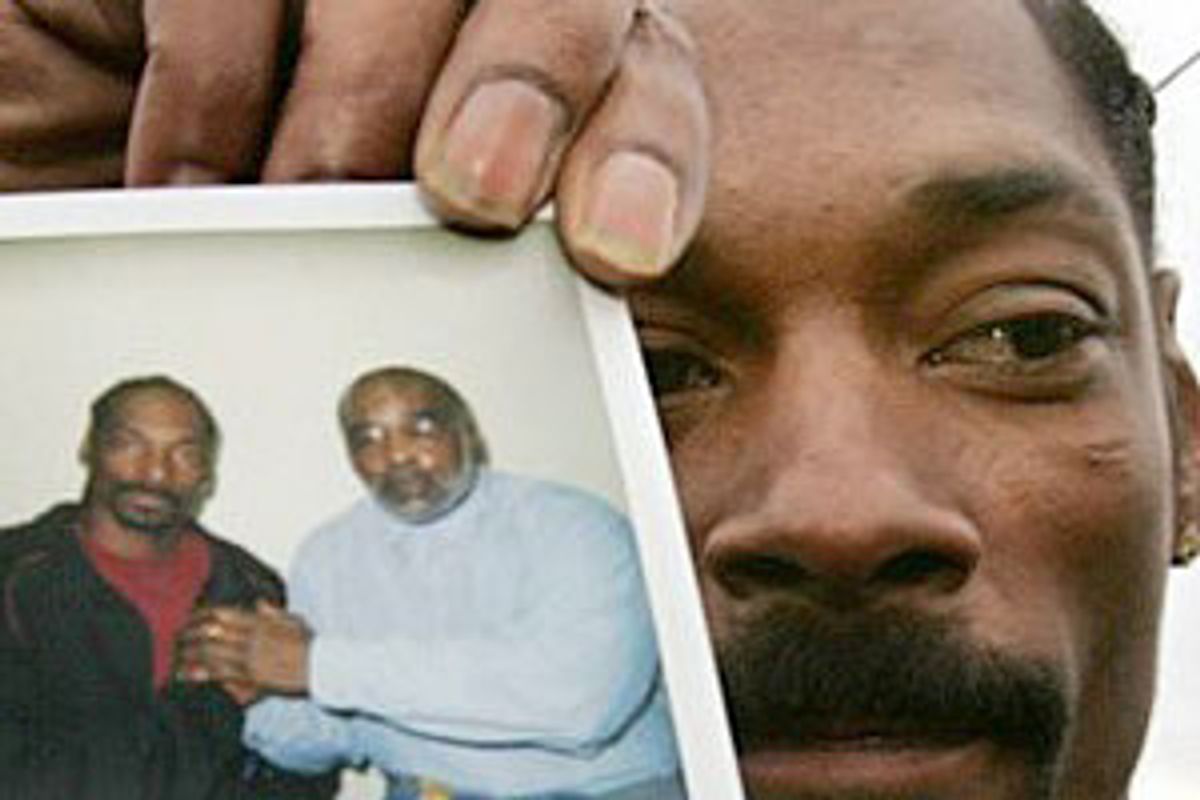

One of Williams' last visitors on Monday was 67-year-old Richmond resident Fred Davis Jackson, who had been coming to see him since 1997. Williams wore his regular blue prison uniform and was in good spirits on Monday, according to Jackson. "This time I couldn't hug him like I wanted to. He was handcuffed; and he's so big, it's hard to get your arms around him." Williams had been on suicide watch, so a guard sat in the room with him. He had refused an official last meal. But there was turkey there, according to Jackson. "He didn't eat any, though," he said. "And I didn't have an appetite neither." The warden later reported that Williams only drank water and milk.

"We said goodbye, like we always do," Jackson said. That was at 6 p.m. It was dark out and getting colder. "I said, 'I'll see you later.' We acted like nothing was going to happen. I gave him a regular goodbye because his faith is so strong. And when I said that I'd see him tomorrow, I was saying that he would be with me no matter what." Soon after, Williams was moved and saw no more visitors.

Earlier Monday, Williams met with several friends and supporters, including the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Becnel. For 10 years, Becnel had helped Williams broker gang truces and carry his message to inner-city youth. She had helped him write a series of books for kids and teenagers. The intent of the books was to inform readers of the perils of gang life, which Williams, who co-founded the Crips gang in Los Angeles, had experienced firsthand.

In the afternoon, outside the prison's main gate, Jackson was harangued by conservative L.A. radio shock jocks John Ziegler and John Kobylt, who were pushing microphones in his face and yelling: "Name one of the victims! Name one." Jackson ignored them and tried to walk away. He never answered the question. "You don't know. Answer the question. You don't know, do you?" At one point, sheriff's deputies stepped in and pushed the men in opposite directions.

Adjacent to the prison sits Point San Quentin Village, a town of 75 people living in quaint houses, condos and cottages nestled into the hill flush against the prison fences.

As night approached, floodlights shone down on Main Street. It looked like a movie set. Some residents had fled. The television and radio trucks were backed into their driveways, lawns and gardens. Reporters worked out of some of their houses, and NBC-TV broadcast from a balcony. Locals charged upward of $2,500 for the space -- the going rate for previous executions had been $1,000. News anchors and reporters were lined up one after the other in their spotlights, and were on every 30 minutes, as if they were doing a play by play.

Actor Mike Farrell -- well known for his role as B.J. Hunnicutt on "M*A*S*H" and as an advocate against the death penalty -- stood before a crowd of gathering protesters and a swarm of media and spoke out against Gov. Schwarzenegger's decision. He said Williams' lawyers met with the governor Dec. 8, then left and they didn't hear from him for 97 hours. "He left Stanley Williams to twist in the wind," Farrell said. "All of us are not only disappointed but are disgusted."

A California Highway Patrol officer told us there were possibly 4,000 people gathered. (More likely the number was closer to 2,000.) But the officer did not say that that number represented a diverse group of African-Americans, Native Americans, whites, nuns, ministers, Buddhists, Christians, Jews and members of the Nation of Islam.

The night wore on and six women -- who called themselves the "Threshold Choir" -- stood in a circle holding burning candles. They sang hymns and prayers. Their voices, almost whispers, were intermittently drowned out by helicopters flying overhead. Below them, people sitting on the beach looked out over the bay, which reflected the dark magenta and violet city light. No one seemed to be talking, as if they were lost in meditation and prayer. Joan Baez sang "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

In the San Francisco Bay Area, people had been gathering for days in support of Williams and in protest against the death penalty. On Sunday, at an American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California ceremony in downtown San Francisco, 700 people showed up to honor Sister Helen Prejean. She received the Chief Justice Earl Warren Civil Liberties' Award. Past winners have included Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall and Farrell, who was there moving through the crowd. But it was clear that Williams was on everyone's mind.

Dorothy Ehrlich, executive director of the ACLU-NC, said, "No one should be put to death without the world watching." Sean Penn introduced Sister Helen. They knew each other from working on "Dead Man Walking" together, the movie that starred Susan Sarandon and Penn, and depicted Sister Helen's experience ministering to Patrick Sonnier and watching him die in the electric chair in 1984 in the state penitentiary in Angola, La. At the ceremony she posed a question to the audience: "What if we put 1,000 condemned people in a stadium and shot them?" And then answered it sharply, "The whole world could see. We have killed 1,000 people and nobody saw."

Earlier that morning, members of the anti-capital-punishment group Death Penalty Focus met in Sausalito, Calif., for a fundraiser brunch. Executive director Lance Lindsey had helped organize it, and organization president Mike Farrell talked informally about Williams to a room of criminal attorneys, professors, business entrepreneurs, a vineyard developer, a private investigator and a psychologist. There were artists and writers. There were people with money. There were liberals who had worked in politics, fundraising and volunteering for various social causes and campaigns.

Farrell, who is tall and has watery blue eyes and white hair, said he met Williams five or six years ago. "He's very impressive. He's very calming, extraordinarily peaceful, given his circumstances," Farrell said. "The transformation -- from his perspective, redemption -- is visible. He's quiet. He speaks like an educated man, interestingly articulate. To use an odd word, he's sweet."

Farrell stood in front of a large fireplace. He had helped defend condemned inmates for more than 25 years, starting just after 1976, when the U.S. reinstated the death penalty. "We all have a finger in it," Farrell said. "We all have a finger in the execution of Stanley Williams." He wore a black coat and sweater, dark navy pants. "We must uphold the American principle that we all have human value, and I believe that issue starts with the death penalty." He articulated the issues, talking of the great inequalities in the system, how poor those on death row are, the discrimination, how most death sentences are carried out in the former slave states.

"People like Stanley, people on death rows across this country, I call them 'the invisible people,'" Farrell said, his hands speaking also, as if he were conducting. "The thinking goes that people who are invisible in our own lives can be dispensed with easily."

He said he knew the pain of those who had lost family members. "I lost a loved one to murder, and I felt great pain, but it doesn't mean I'm going to stoop to the lowest part of my self."

"I spoke with a woman who lost her loved one in the Oklahoma City bombing," he continued. "She said she didn't want Timothy McVeigh to be executed. She said, 'No, I want him to be skinned alive.' She wanted him to be tortured every day for this rest of his life. Though I understand the feeling, we cannot, as a society, condone anyone acting on those feelings. Otherwise we might as well strap an inmate to a chair, and give the grieving family an ax and have them go out at them, and let there be blood on the walls."

There was silence in the room. A woman with her legs folded beneath her on the couch looked as if she might cry.

After midnight on Monday, plenty of people were crying. Following the execution, people trickled down the dark street, and Penn was among them. We asked him how one could ultimately make an invisible person visible. "I feel the answer to your question is right here, among all these people, who came to say what's on their mind, what's in their hearts," he said. And why was he there walking among them, lost in the crowd in his black jacket and faded blue jeans, an unlit cigarette in hand? "For the same reasons these people are here. I'm here to abolish the death penalty."

Shares