One day in the fall of 1985, a small boy captured a tiger in a trap (using a tuna fish sandwich as bait, of course). The newspaper-reading public was immediately enraptured, first in the United States and then around the world, without yet understanding that they were witnessing the birth of the last great newspaper comic strip in the form’s history. That strip was Bill Watterson’s “Calvin and Hobbes,” and it occurred to me while watching Joel Allan Schroeder’s slight but agreeable documentary “Dear Mr. Watterson” that I’ve never heard anyone explore the question of why these two beloved characters are named after such forbidding figures in the history of British moral and political philosophy.

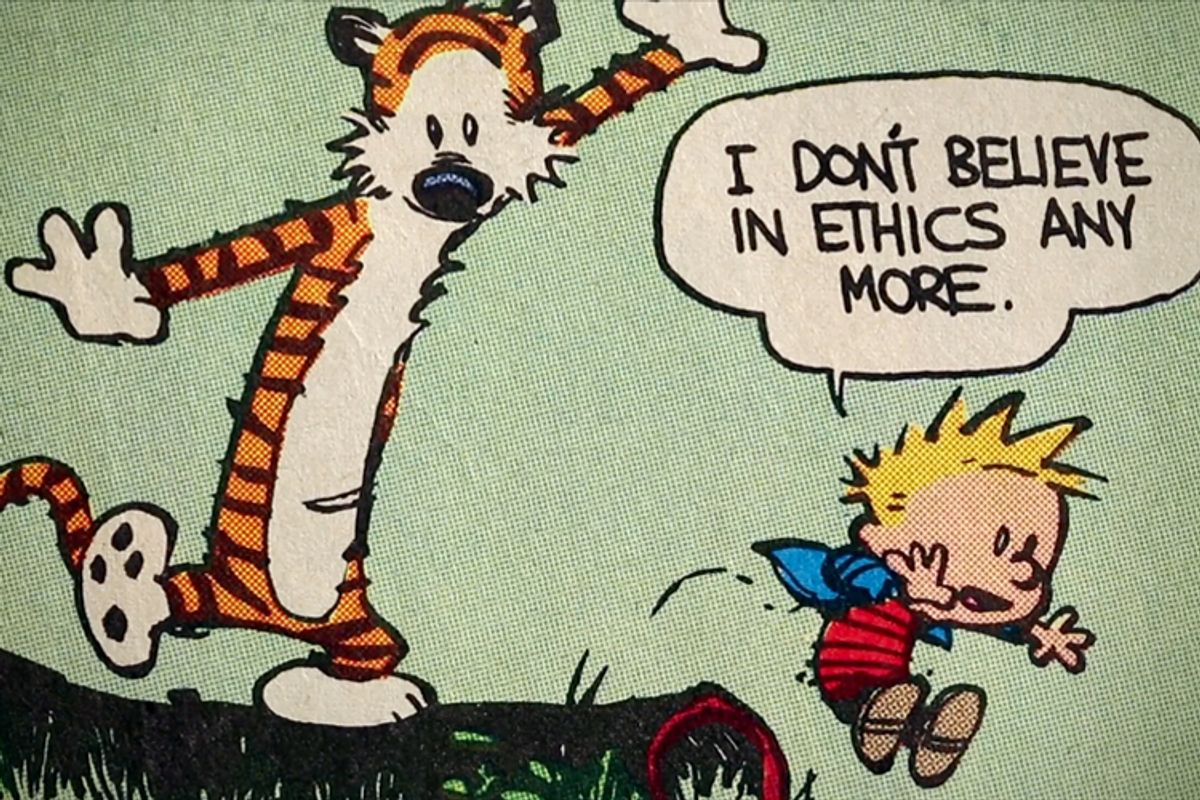

It’s hard to imagine a reader who doesn’t know this, but Calvin is an imaginative, inquisitive and entirely reckless boy of about 6 or 7, and Hobbes is his somewhat more prudent tiger companion, who often functions – albeit ineffectively – as Calvin’s conscience or superego. (To adults inside the strip, Hobbes appears to be a stuffed toy. We, and Calvin, know different.) Their adventures, set entirely in a mythic Middle American landscape that’s partly “Peanuts” and partly “Huckleberry Finn,” range from the straightforward, realistic and sentimental (setting aside the question of how “realistic” a comic strip can ever be) to the satirical and the flat-out surreal, even the postmodern and the meta-textual.

Perhaps you remember the T-rex who sometimes ran roughshod over the playground during school recess, or the vicious and dangerous “snow-goons” summoned to life in winter. Calvin can never resist mashing the button on the Transmogrifier (although it’s never a good idea), and neither could Watterson, who might draw an entire Sunday strip in “neo-cubist” style, or in hilarious imitation of long-gone story comics like “Mary Worth.” As with Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts,” there are very few direct references to the world outside of childhood, although the strip always had a large adult audience and Calvin and Hobbes’ philosophical disputes play very differently to audiences of different ages. But you don’t need to understand the pop-culture or political context of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s to enjoy “Calvin and Hobbes,” which may be why children (my own included) eagerly devour it today.

Any “Calvin and Hobbes” fan will enjoy watching Schroeder’s film, which is more a love letter to the strip and its publicity-shy creator than anything else. “Dear Mr. Watterson” is a work of charming reportorial energy, in which Schroeder (who wrote, directed and edited the movie) interviews many prominent fans and friends of Watterson – including “Bloom County” cartoonist Berkeley Breathed and actor Seth Green – and handles original “Calvin and Hobbes” artwork now in a comics archive at Ohio State. Schroeder’s passion for the material comes through clearly, and he correctly identifies a note of ruefulness – a sort of American-Zen reflection on the ephemeral and transient nature of all experience – that runs through Calvin and Hobbes’ adventures even at their most joyful. Watterson’s haunting and ambiguous final strip from 1995 -- with its largely empty concluding panel -- is one of the great pop-culture sendoffs, up to and including the last episode of “The Sopranos.”

But Schroeder isn’t much of a comic-strip expert or historian, by his own admission, so “Dear Mr. Watterson” bounces off many of the most interesting issues in and around “Calvin and Hobbes,” noticing them but not exploring them deeply. As various of Watterson’s fellow cartoonists point out, “Calvin and Hobbes” was the last in a historical line of fanciful or allegorical newspaper comics that attracted a large popular audience while pushing at the artistic and conceptual limits of the form. This tradition goes back at least as far as Winsor McCay’s “Little Nemo in Slumberland” (which debuted in 1905) – a major formal and structural influence on Watterson -- and then continues through George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat” and Walt Kelly’s “Pogo,” still viewed by comics devotees as the two greatest newspaper strips of all time. Like each of those three pioneers, Watterson treated the full-color, large-format Sunday comic as a zone of free-form experimentation, insisting on full editorial control.

I think that context is crucial to understanding Bill Watterson, and what he did and didn’t do. He was a struggling editorial cartoonist, nearly unknown outside northeastern Ohio (his hometown is called Chagrin Falls, which has to be one of the greatest American small-town names), when he suddenly leapt to fame with “Calvin and Hobbes,” which became an international hit within a year or two. He had the opportunity to become immensely rich off his strip and its characters – one industry expert in Schroeder’s film suggests that licensing and merchandising could have brought in $300 million or more – and refused to license anything, ever. There are no official Hobbes plush toys or Calvin action figures and never have been, although the world is full of unlicensed knockoffs: YouTube animations and Japanese video games and Calvin on the back of somebody’s pickup, peeing on the Dodge logo or kneeling before the cross.

If that wasn’t un-American enough, not to mention deeply contrary to the spirit of our age, Watterson published his comic strip for 10 years and then quit, without much advance warning, when it was still massively popular. As he told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 2010, in one of the two known interviews he’s done in the last 20 years, “I’d said pretty much everything I had come there to say. It’s always better to leave the party early … I think some of the reason ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ still finds an audience today is because I chose not to run the wheels off it.” Watterson apparently still lives in Ohio (although not in Chagrin Falls) but whatever he’s been doing for the last 18 years, it does not involve cartooning for public consumption. He’s not quite J.D. Salinger – he reviewed a “Peanuts” anthology for the Wall Street Journal in 2007 – but keeps a very low profile.

“Calvin and Hobbes” has been immensely influential – but mostly in TV animation, in stand-up and sketch comedy, and in graphic novels and in Internet culture. The newspaper comic, like the newspaper itself, has lost its social meaning. One way of understanding Watterson’s decision to quit, and also the melancholy tone his strip had all along, is that he knew or guessed that the McCay-Herriman-Kelly-Schulz lineage of great newspaper comics was coming to an end, and that “Calvin and Hobbes” was its last hurrah. That doesn’t mean that comics or cartooning are dead, not by a long shot. Comics in the 21st century are an immensely fertile field, and a more respectable artistic form than they’ve ever been before. They’re also a niche product, like almost everything else in our flattened, atomized media landscape that isn’t a superhero or a Kardashian. Watterson quit at precisely the right moment; “Calvin and Hobbes” never became “Garfield” and never became insignificant. When the Plain Dealer asked him about the Postal Service’s “Calvin and Hobbes” stamp, Watterson said he planned to use it immediately: “I’m going to get in my horse and buggy and snail-mail a check for my newspaper subscription.”

"Dear Mr. Watterson" opens this week in Los Angeles, New York, Santa Fe, N.M., and Toronto. It opens Nov. 22 in Albuquerque, N.M., Phoenix, Portland, Ore, and Spokane, Wash.; Nov, 29 in Miami; Dec. 1 in Dallas; and Dec. 6 in Cleveland, Grand Rapids, Mich., New Orleans and Columbus, Ohio, with more cities to follow. It's also available on VOD via cable, satellite, iTunes and other providers.

Shares