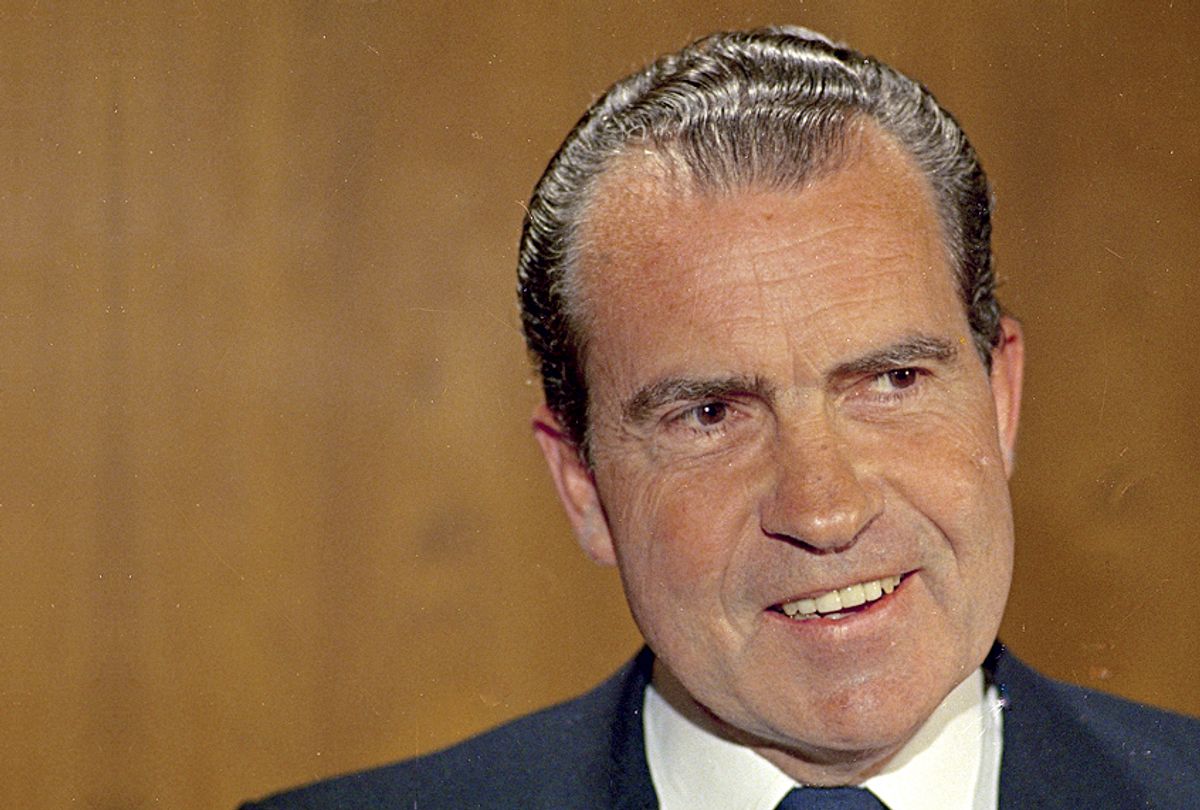

The Republican nominee colluded with a foreign government to win the presidential election. The nominee was Richard Nixon, the foreign government was South Vietnam, and the election was 1968. This “sordid story,” as then-President Lyndon B. Johnson described it to Nixon (in a telephone conversation LBJ secretly tape-recorded), is one of the many narrative threads masterfully woven by directors Ken Burns and Lynn Novick into episode seven of "The Vietnam War," titled “The Veneer of Civilization (June 1968–May 1969).” LBJ did not exaggerate. “Sordid” is a mild way to describe the ruthlessness with which Nixon put his political interests above all else, including the law, the truth and the lives of American soldiers.

For most of 1968, Nixon was the presidential race’s clear front-runner. In a year of violence — the Tet offensive, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, the riots in Chicago and so many other American cities — Nixon’s candidacy hearkened back to the tranquil years of the Eisenhower administration, when Nixon had been Vice President. Candidate Nixon promised to restore law and order at home (a theme that played on racist fears as well as a real rise in the crime rate) and to achieve peace with honor abroad. He saddled his Democratic opponent, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, with all of the baggage of the 1960s — crime, disorder, Vietnam. By September of 1968, Nixon led Humphrey in the Gallup poll by 15 points.

But Nixon ran scared. He realized that President Johnson had it in his power to do one thing that could make Nixon lose. In March, Johnson’s popularity had skyrocketed when he announced that he was placing nearly 90 percent of North Vietnam off limits to aerial and naval bombardment. At that time, Johnson offered to stop the bombing completely if the North agreed to prompt, serious peace talks. This was Nixon’s nightmare: that Johnson would announce the end of the bombing and the start of peace talks before Election Day, causing the president’s standing in the polls to rise — and lifting Vice President Humphrey’s with it. Nixon was not going to let that happen if he could help it.

Publicly, Nixon said the right things. Accepting the Republican nomination, he said, “We all hope in this room that there’s a chance that current negotiations may bring an honorable end to that war, and we will say nothing during this campaign that might destroy that chance.” That was the first presidential promise he would break.

By the time he made it, Nixon had already set up his own private backchannel to the South Vietnamese government. To conceal his hand, he used a cutout, a top Republican fundraiser named Anna C. Chennault. She introduced Nixon to South Vietnamese Ambassador Bui Diem the month before the Republican convention. At that time, Nixon told Diem that Chennault would be his representative to the South Vietnamese government. Secrecy was paramount, so much so that Nixon concealed the fact that the meeting took place from his own Secret Service detail.

That meant Secret Service agents could not inform President Johnson of the meeting, even if questioned. Nixon was portraying himself to Johnson (and the country) as the picture of bipartisanship and patriotic loyalty. And Nixon really did support the President — as long as Johnson didn’t order a bombing halt.

It was easy at first, since Johnson’s proposal was rejected by the North, which demanded that he stop the bombing “unconditionally,” without any “reciprocity” on its part. Johnson had conditions, military as well as diplomatic. In return for a bombing halt, North Vietnam would not only have to agree to peace talks with South Vietnam, it would also have to stop shelling South Vietnamese cities and start respecting the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that divided Vietnam. Johnson briefed Nixon on his three conditions, and Nixon backed them all. (The more conditions Johnson had, the less likely the North Vietnamese were to accept them, so the more likely it was that Nixon would be able to cruise to victory without having to worry about the political impact of a bombing halt.)

Throughout the negotiations, Johnson stuck resolutely to his three conditions, demanding that the North (1) enter peace talks with the South, (2) respect the DMZ and (3) stop shelling Southern cities. The North just as resolutely rejected all three.

Until one month before the election, when North Vietnam reversed itself and suddenly accepted all three of Johnson’s conditions. At that point, Johnson balked. He feared that the North was trying to elect Humphrey — with the backing of Moscow, America’s primary Cold War adversary. (LBJ was right about Moscow. It feared Nixon’s reputation as a cold warrior, and secretly offered Humphrey help — including, according to Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, “financial aid.” Humphrey rejected the offer immediately.) Johnson also feared that the North would not keep its end of the deal. Most of all, Johnson feared that a bombing halt would look like a political move by the old wheeler-dealer LBJ to elect another Democrat. Johnson would not be able to defend himself against the charge very well, since he could not afford to reveal that the North Vietnamese had accepted all of his conditions. “We don’t want to call it reciprocity, we don’t want to call it conditions,” Johnson said to the presidential candidates in an October 16 conference call, “because they object to using those words, and that just knocks us out of an agreement.” Publicly, Johnson would not mention his military conditions regarding the DMZ and the cities at all, fearing that doing so would cause the agreement to fall apart.

Nixon told him, “I’ve made it very clear that I will make no statement that would undercut the negotiation.”

Behind LBJ’s back, however, Nixon did make statements to undercut the negotiations. As biographer John A. Farrell discovered while researching his masterful "Richard Nixon: The Life," Nixon told his chief of staff H.R. Haldeman to “keep Anna Chennault working on SVN [South Vietnam]—insist publicly on the 3 Johnson conditions.” Nixon did this on October 22, well after President Johnson had warned him that making the three conditions public would destroy the agreement. Nixon’s attempt to sabotage the negotiations failed this time, since South Vietnam did not make LBJ’s three conditions public. Nevertheless, the attempt violated the Logan Act, which prohibits American citizens from interfering with the diplomatic negotiations of the U.S. government. The attempt also gave the lie to Nixon’s promise to Johnson and America that he would do nothing to undercut the negotiations. Worst of all, the attempt put Nixon’s election above the human lives that would be lost if a bombing halt agreement was not reached, including the lives of American soldiers, who would continue to be subject to artillery fire across the DMZ, and the lives of South Vietnamese civilians, who would continue to be subject to artillery attacks on their cities.

By the time Nixon made the attempt, reports that a bombing halt was in the works had cut his lead in the polls nearly in half — to 8 points. Recognizing the issue’s political power, LBJ fretted about how a bombing halt before the election would look. “Now, you and I can’t have our reputations ruined the rest of our life — that they’re trying to elect Humphrey,” he said to Secretary of State Dean Rusk on October 23. Johnson said he would campaign for Humphrey, “but damned if I’m going to throw a peace for him.”

But Rusk said Johnson’s reputation could be ruined by his own record if he refused to stop the bombing even after the North had accepted his military conditions. Johnson’s hawks, “the architects of the war,” were now urging him to make the deal. The U.S. military commander in Vietnam, General Creighton W. Abrams, told him that the deal would be to America’s military advantage. A halt to the bombing of the North would enable Abrams to send more American aircraft into Laos to bomb North Vietnamese supply lines, and the North’s military concessions would enable him to send the troops that had been defending the DMZ and the cities into the countryside to conduct offensive operations. Abrams advised the president to make the deal. “I have no reservations about doing it,” Abrams said. “I know it is stepping into a cesspool of comment.”

On the day President Johnson made up his mind — October 29, one week before Election Day — he learned that the Nixon campaign was trying to torpedo the deal. The information came from an extraordinary man, Alexander Sachs, a Wall Street economist famous for warning President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Nazi Germany might build an atom bomb, a warning that led to the Manhattan Project. Sachs was also credited with giving accurate warnings about the Great “Depression, the 1933 banking crisis, and the rise of Hitler,” according to The New York Times. Now, Sachs privately warned the President that Nixon was trying to block the start of the peace talks. Nixon “would incite Saigon to be difficult,” Sachs said.

The warning prompted the President to take a closer look at his diplomatic intelligence. At the time, the National Security Agency was intercepting cables from the South Vietnamese embassy to Saigon, and the Central Intelligence Agency had a bug in the office of South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu. LBJ picked up enough from the NSA and CIA reports (which remain partly classified) to get an idea what Anna Chennault and Ambassador Diem were up doing. “She’s around town and she is warning them to not get pulled in on this Johnson move. Then he, in turn, is warning his government,” Johnson said. But the NSA and CIA had no direct evidence against Nixon himself. President Johnson asked the Federal Bureau of Investigation to follow Chennault and wiretap the embassy.

In a televised address on October 31, President Johnson announced a halt to the bombing and the start of peace talks with the North “in which the Government of [South] Vietnam was free to participate.” Nixon’s lead in the polls evaporated. The final Gallup poll before the election showed the race within the margin of error.

But on November 2, the Saturday before Election Day, President Thieu publicly announced that South Vietnam was boycotting the Paris peace talks. Thieu said that the North would “bring along the National Liberation Front [NLF] as a separate delegation” and that this “would just be another trick toward a coalition government with the Communists in South Vietnam.” In reality, Johnson had insisted that the NLF (the political wing of the Vietcong) could not participate in the peace talks as a separate delegation and had ruled out a coalition government for South Vietnam. Thieu’s objections were pretexts. He objected to holding peace talks at all, since he thought they would provide a pretext for American withdrawal and thereby doom South Vietnam to a Communist takeover. He also preferred Nixon, the prominent Cold Warrior, to Humphrey, the liberal who had privately objected to the Americanization of the war in the first place. Regardless of his real motives, Thieu’s refusal to take part in the peace talks made the bombing halt look like a political ploy by Johnson, a sellout to the Communists to win an election.

That same day, Johnson got an FBI wiretap report confirming that the Nixon campaign was secretly encouraging Thieu’s boycott. On the tapped embassy phone, Chennault told Ambassador Diem “that she had received a message from her boss (not further identified),” the FBI report said. The message: “Hold on, we are gonna win.”

Furious, Johnson called the highest-ranking elected Republican in the land, Senate Minority Leader Everett M. Dirksen, R–IL, and threatened to expose the Nixon campaign.

President Johnson: Now, I’m reading their hand, Everett. I don’t want to get this in the campaign.

Dirksen: That’s right.

President Johnson: And they oughtn’t to be doing this. This is treason.

Dirksen: I know.

The next day, Nixon called Johnson and protested his innocence.

Nixon: I just wanted you to know that I got a report from Everett Dirksen with regard to your call. And I just went on Meet the Press and I said that—on Meet the Press—that I had given you my personal assurance that I would do everything possible to cooperate both before the election, and if elected, after the election. And that if you felt, the Secretary of State felt, that anything would be useful that I could do, that I would do it. That I felt Hanoi—I felt that Saigon should come to the conference table, that I would—if you felt it was necessary—go there, or go to Paris, anything you wanted. I just wanted you to know that I feel very, very strongly about this, and any rumblings around about [scoffing] somebody trying to sabotage the Saigon’s government's attitude there certainly have no—absolutely no credibility as far as I’m concerned.

President Johnson: That’s—I’m very happy to hear that, Dick, because [Nixon attempts to interject] that is taking place.

One day before the election, the White House was asked to comment on a story that the Christian Science Monitor had not yet decided whether to publish. The lede: “Purported political encouragement from the Richard Nixon camp was a significant factor in the last-minute decision of President Thieu’s refusal to send a delegation to the Paris peace talks— at least until the American Presidential election is over.”

Johnson was torn. He held a conference call with Secretary Rusk, National Security Adviser Walt W. Rostow, and Defense Secretary Clark M. Clifford.

President Johnson: Now, I don’t want to have information that ought to be public and not make it so. On the other hand we have a lot of . . . I don’t know how much we can do there, and I know we’ll be charged with trying to interfere with the election, and I think this is something’s going to require the best judgments that we have.

Rusk was opposed to making any comment to the newspaper.

Rusk: Well, Mr. President, I have a very definite view on this, for what it’s worth. I do not believe that any president can make any use of interceptions or telephone taps in any way that would involve politics. The moment we cross over that divide, we’re in a different kind of society.

Clifford, a fixture of Democratic politics since the Truman administration, agreed with Rusk.

Clifford: I’d go on to another reason also, and that is I think that some elements of the story are so shocking in their nature that I’m wondering whether it would be good for the country to disclose the story and then possibly have a certain individual elected. It could cast his whole administration under such doubt that I would think it would be inimical to our country’s interests.

Rostow agreed with both. President Johnson made no comment. The Monitor decided not to run the story. On Election Day, Nixon won by less than a percentage point. The final tally was Nixon 43.4 percent, Humphrey 42.7 percent.

Nixon betrayed President Thieu within days of the election. South Vietnam continued to boycott the peace talks even after the votes were counted, since President Thieu believed that talks would eventually lead to American withdrawal and Communist victory. President Johnson persuaded Nixon to privately issue an ultimatum to the South Vietnamese by threatening him with exposure of his campaign’s secret sabotage of the peace talks. It was “killing Americans every day. I have that documented. There’s not any question but what that’s happening,” President Johnson said. He told Nixon to inform South Vietnam that it would lose American support if it didn’t take part in the peace talks. Nixon agreed to send Dirksen to deliver the bipartisan ultimatum on behalf of the Democratic President and the Republican President-elect. South Vietnam immediately dropped its objections to participating in the peace talks. After all, South Vietnam depended on American aid for its existence. (Thieu’s immediate about-face explains why Nixon felt he had to secretly urge South Vietnam to boycott the peace talks. If Thieu had thought that candidate Nixon truly meant what he said in public in favor of the peace talks, he would not have dared risk losing American support by defying both parties. Thieu wanted to boycott the peace talks anyway, but he could not afford to do what he wanted if it would lead to loss of the American support on which his government depended for its survival.)

President Johnson’s decision not to reveal to the American people what the NSA, CIA and FBI had uncovered regarding Nixon’s secret sabotage of the peace talks had far-reaching consequences. As President, Nixon would continue to put his political interests above the law, the truth, and the lives of American soldiers and the people of Vietnam. One consequence was Watergate. Another was Nixon’s decision to add four more years of a war he knew he could not win, but could not afford to lose before his reelection in 1972. The most dire consequence for President Thieu was Nixon’s negotiation of a “peace” accord that merely delayed the day the Communists finally overthrew the South Vietnamese government for a “decent interval” following American withdrawal. Those consequences are examined in episode nine of "The Vietnam War," “A Disrespectful Loyalty (May 1970–March 1973).”

Shares