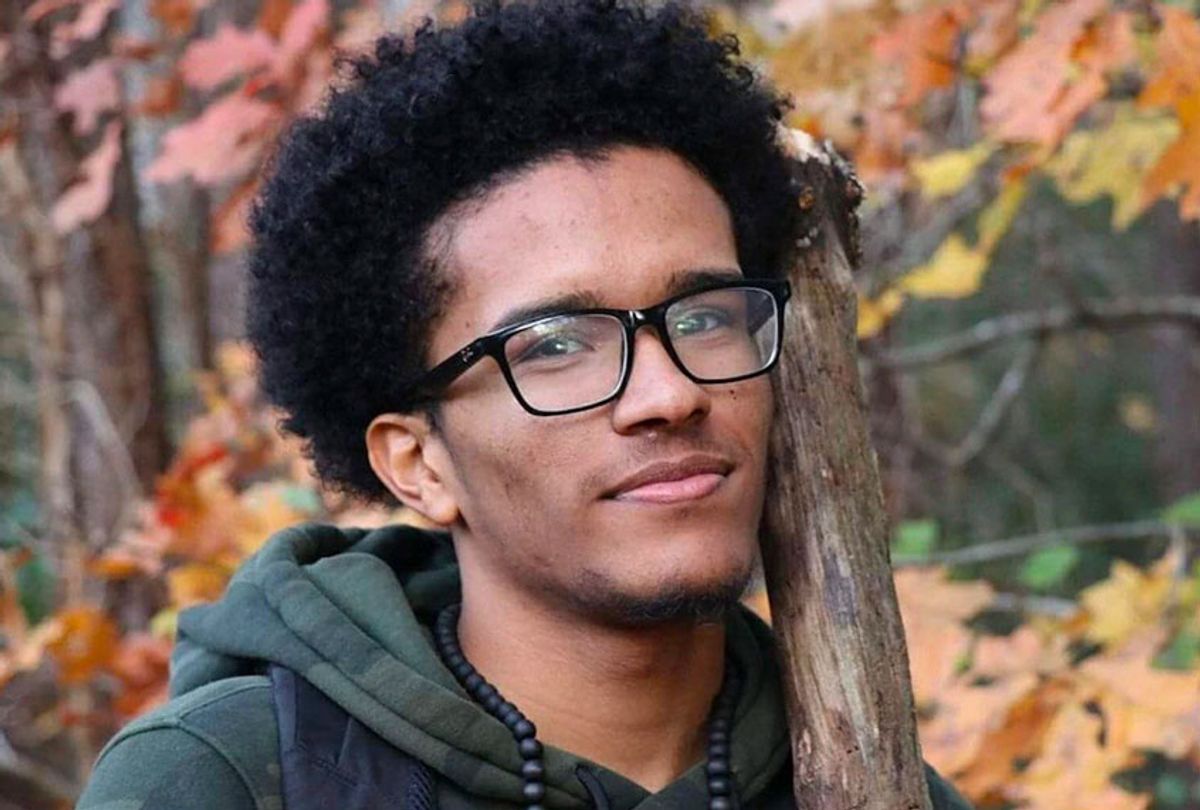

The ongoing Black Lives Matter protests have thrust police racism and brutality into the public consciousness, bringing to light many individual instances of injustice that were ignored previously. One of the most notable is that of Virginia's Matthew Rushin, a Black autistic man whose surprisingly long prison sentence is finally getting the scrutiny it deserves.

Matthew Rushin was 19 years old last year when he pleaded guilty to malicious wounding and felony hit and run, eventually receiving a 50-year prison sentence (a judge ordered that he had to serve 10 of them). Rushin was responsible for a car collision that put a 72-year-old man, George Cusick, into a coma for nearly two months and reportedly rendered him unable to talk, feed himself or recognize his family members. The controversy emerges from the fact that Rushin signed a plea deal which his mother claims he did not understand; Rushin was diagnosed with ADHD and Asperger's Syndrome as a child and later experienced a traumatic brain injury.

The incident that sent Rushin to jail occurred because, while on a trip to pick up pastries at a Panera where he worked, he accidentally struck another moving vehicle in a parking lot, fled and then had another car collision. Prosecutors claimed that he was trying to kill himself by citing words he said that others claim were taken out of context, but his defenders insist that it was a genuine car accident. The Old Dominion University engineering student's mother says he simply made a driving mistake while trying to do a U-turn to return to the scene of his initial accident.

Terra Vance, an autistic woman and psychology consultant, studied the case in depth and concluded that it was a regular car accident without suicidal intent. She published a letter from a forensic engineer and traffic collision reconstruction expert who studied the evidence and likewise concluded that it does "not support the theory of suicidal behavior or attempted homicide" but rather "strongly suggests pedal misapplication as the primary collision factor." This is supported by the fact that he told police during his interrogation that he had applied his brakes, tried to stop and did not intend to hurt anybody.

The forensic engineer's letter also notes that poor executive function is common in autism and ADHD. (I can relate: this author is on the autism spectrum and, because of his executive functioning disability, cannot drive.) Rushin is still in prison, where his mother claims he has received neither mental health care nor attention for the headaches, dizziness and transient blindness he has suffered since the crash.

"My heart goes out the Cusick Family, but accidents happen everyday and no one died," a Change.org petition purportedly written by Rushin's mother explains. "My son is NOT a killer. Matthew is very remorseful and wishes he could take the place of those are in pain."

Rushin's story brings to mind the case of Neli Latson. When he was 18 years old in 2010, the Virginian special-education student — who had been diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome when he was in the 8th grade — was sitting outside of a library when an anonymous person called complaining of "suspicious" behavior. (The caller also claimed he was possibly carrying a gun, although an investigation revealed that the caller had not seen a firearm.) Latson had not committed any crime but, according to a civil rights lawsuit filed by his mother, the deputy who approached him grabbed him several times while the two interacted with each other. Laton responded with "a fight-or-flight response, which is a common response for individuals with [autism spectrum disorder] who are faced with these types of situations," according to the lawsuit.

Because the deputy got hurt, Latson was sent to jail, where he was often held in solitary confinement for long periods (including once for over 100 days). On one occasion he was Tasered and strapped to a restraint chair. Although the jail which Tasered him paid a settlement and has since limited the use of isolation for inmates with intellectual disabilities and mental illnesses, Latson's claims against the Virginia Department of Corrections were dismissed on the basis of "qualified immunity." He was later given a conditional pardon by then-Gov. Terry McAuliffe but Arc, a national advocacy organization for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, is urging Gov. Ralph Northam (D) to grant Latson a full pardon.

"Thinking about Matthew Rushin, and then the situation with Neli Latson, I wish I could say that these situations were rare, but they're not," Morénike Giwa-Onaiwu, a board member of Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network, told Salon. "They might not always escalate to the point of death or arrest, but these type of interactions with authority figures are not rare. This is our normal."

Giwa-Onaiwu noted that, as an African American woman who is on the autism spectrum, she has also had tense encounters with the police.

"It may not be discussed openly in the media, but there is evidence that a lot of the individuals themselves have some form of a disability with regard to these frequent relations," Giwa-Onaiwu explained. "Even personally: I'm a Black woman and autistic and I have personally had interactions with police officers that have frightened me, where I worry about my safety in subsequent situations where I had some difficulty with auditory processing or communication, or I had a spinning device in my hand, in the vehicle, that was a metal coil that was mistaken for a weapon."

She later added, "A person who is autistic, who is not a person of color, obviously still faces ableism and a lot of other bigotry in society. So speaking for myself and hopefully on behalf of some people in my community who agree, we want our white autistic allies to use the experiences that they've had to try to relate to us." Giwa-Onaiwu commented that often within the autism community, people will ask why race is brought up in those conversations.

"It's almost like the conversation gets shut down. No one wants to discuss these elements, but they're very real," she added

Shares