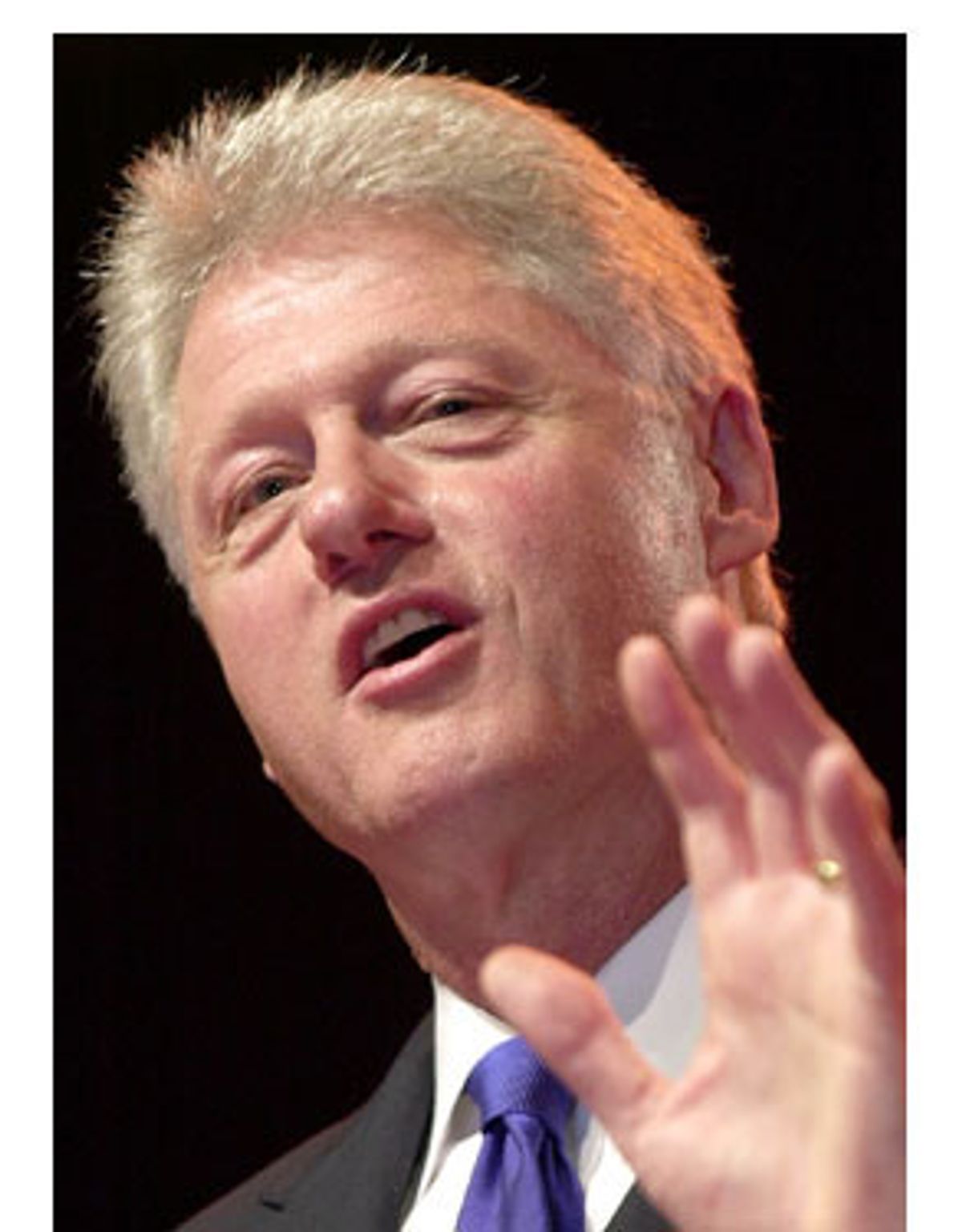

Editor's note: Former President Bill Clinton delivered the following remarks before the Labor Party Conference in Blackpool, England, on Wednesday. The speech, which ranged from Africa to Iraq to his differences with Bush conservatism, was hailed in the Guardian as the work "of a true political master ... At times, it was as if Mr. Clinton was calling on Mr. Blair to rescue America from Bushism ... What a speech. What a pro. And what a loss to the leadership of America and the world." The Mirror was even more exuberant: "It was a magnificent speech from a man who is rapidly becoming the greatest figure in world politics, second only, perhaps, to Nelson Mandela."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Bill Clinton

Oct. 3, 2002 | I am trying to imagine what in the world I am doing here. I have never been to Blackpool before, I had never been to the McDonald's in Blackpool before. I like the city, I like the weather, and I understand I may have brought it; if so I will take credit for any good thing I can these days. I accepted when Prime Minister Blair asked me to come because he and Cherie are old friends, because I love this country and feel deeply indebted to it. It gave me two of the best years of my life and I think my daughter is getting two of the best years of her life here as well. (Applause).

I am sort of getting used to being the spouse of an election official instead of one, but it is flattering when someone who no longer has a shred of power is asked what he thinks, so I thought I would show up and say it. It is also fun to be in a place where our crowd is still in office and I am glad to be here. (Applause). But the real reason I came here today is because politics matters. It matters to the people whom you represent, and because we live in an interdependent world and what you do here matters to all of us across the globe.

I have just come here from a trip to Africa which provided me with all kinds of fresh evidence of the importance of politics. I spent a week working on issues that are central to the mission I follow now that I am no longer in office and to the future of Africa; increasing economic opportunity for the continent's poor, fighting HIV and AIDS, building bridges of reconciliation between races, tribes and religions, supporting still new democracies. Time and again I was reminded of the importance of politics to the lives of ordinary people.

(I visited) Ghana where a new president is working with a great Peruvian economist, Hernando De Soto, to bring the assets of poor people -- their houses, farms, businesses -- into the legal system so they can be collateral for loans and they can grow their own families' incomes and the nation's income. I met a woman there who gave me a shirt made in a factory of 400 Ghanaians that came into being because of the trade bill I signed in 2000 in Nigeria, where decades of corruption and poverty amidst all that oil wealth had led some of the states in desperation to adopt Shariya law, under which a young mother of three was recently sentenced to death by stoning for bearing her last child out of wedlock -- and where I pled for her life.

(I also visited) Rwanda, where the government has established a reconciliation village and welcomed me with amazing evidence of new beginnings in the aftermath of the terrible genocide just eight years ago which claimed the lives of over 10 per cent of the country's population. I met a Tutsi widow in that village whose husband died in the slaughter, standing right next to her neighbor, a Hutu woman whose husband is in prison awaiting trial for participating in the slaughter. I saw Hutu and Tutsi children dancing together in a ceremonial dance for me, for what the governor said was the very first time since 1994. These kids were smiling again, they were young again, they were beginning to trust each other again because of a decision made by the government to establish a village and to welcome them all to come and live together.

In Mozambique I saw the president, Mr. Chissano, who is struggling to fight AIDS, overcome the effects of massive flooding and build a modern economy. In South Africa I met with university students who are looking past all their problems with confidence towards a multi-racial democratic future. I saw President Mbeki leading the continent to adopt Africa's very first home- grown economic plan called NEPAD: it is a third-way document because it calls on the developed world and Africa to work in genuine partnership and assume mutual responsibilities; and I saw Nelson Mandela, 84 years young, still getting me to do things he wants me to do. (Applause)

On this particular day he got me involved in his effort to challenge young people to take personal responsibility for reversing the AIDS epidemic through prevention and engaging in more citizen service. So politics matters, and even if you are a former president there are some things that we can accomplish for the common good only through the common instrument of our elected officials.

It was a wonderful trip and I had such a good time, I asked one of my traveling companions to come with me today, Kevin Spacey, who is over here. (Applause).

Since humanity came out of Africa eons ago, the whole history of our species has been marked by human beings' attempts to meet their needs and fulfill their hopes, confront their dangers and fears, through both conflict and cooperation. We have come to define the meaning of our lives in relationship to other people. We derive positive meanings through positive associations with our groups and we give ourselves importance also by negative reference to those who are not part of us. There has never been a person in any age, and I bet it applies to everyone in this room, who has not said at least once in your life to yourself if not out loud, "Well, I may not be perfect but thank God I am not one of them." That has basically been the pattern of life. But since people first came out of caves and clans, we have grown ever more steadily inter- dependent and wider and wider in our circle of relations. And that has required us constantly to redefine the notion of who was "us" and who is "them."

Yet the prospect for a truly global community of people working together in peace with shared responsibilities for a shared future was not institutionalized until a little less than 60 years ago with the creation of the United Nations and the issuance of the universal declaration of human rights. Such a community did not even become a possibility until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

The history of civilization as we know it -- with writing and urban life -- is just a little over 6,000 years old. Human beings have been on the planet, depending on how you read the evidence, somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 years. I say that to begin on a note of optimism. The world has a whole lot of problems, but we have not had a chance to bring it together for very long. You should be upbeat and grateful that your party is in power at a time that you have a chance to make all the difference in the world. (Applause).

So, here we are in this interdependent world of open borders, easy travel, mass migration, universal access to information and technology, drenched in global media. I will just give you a stunning example that occurred to me on the way over here. When Kevin and I walked over to the hotel and got into our van to ride here, his cellphone rang and two friends of ours were calling from Paris to say they had just watched us walk out of the hotel in Blackpool, and how nice we looked. So I said, "Well, it's a slow day for news in Paris," but it is a good example of our interdependent world.

This world has brought great benefits to the British people and the American people and to people everywhere who are prepared to make the most of it and have the right values, the right vision and do the right things. But there is a big problem with our interdependent world; it does not include a lot of us yet.

Half the world's people live on less than $2 a day, a million people live on less than a dollar a day, including people in three of the five nations I visited on my recent trip to Africa.

A billion people are hungry every night, a billion and a half people never have any clean water, 130 million kids never go to school, 10 million children die every year of preventable childhood diseases, even though overall life expectancy is up and infant mortality down, even in the developing world.

One in four people this year who perish will die of AIDS, TB, malaria and infections related to diarrhea. And it is not just the economic, health and education divides; there are large numbers of people who simply do not have the values and vision necessary to be part of an interdependent world because they think their differences -- whether they are religious or political or racial or tribal or ethnic -- are more important than our common humanity. They believe the truth they have justifies their imposition of that truth on other people, even if it means the death of innocents.

What happened to us in September 2001, is a microcosmic but painful and powerful example of the fact that we live in an interdependent world that is not yet an integrated global community -- which means that people who do not share the same values and vision and interests still have access to open borders, easy travel, technology and information that the al-Qaida network used to murder 3,100 people in the United States, including over several hundred Muslims and over 200 British citizens, among those from over 70 countries who perished.

It would be boring if we were all the same. Britain and America are more interesting countries than they were 30 years ago because they are more diverse. But the only way we can really live together is if we say that the celebration of our differences requires us to say that our common humanity matters more. (Applause)

There are a lot of obstacles in the road towards that kind of world. There are terrorists, there are tyrants, there are weapons of mass destruction, there are all these people who are not part of our prosperity -- and there are a lot of people on our side who think that we can for ever claim for ourselves what we deny to others. There are a lot of obstacles in the way. But let us be realistic; none of you believe that we will ever be completely defeated by terrorists. We will not allow ourselves to be defeated by tyrants with weapons of mass destruction; that will not happen. But we could reduce the future that we can build for our children if we respond to the challenges in the wrong way.

Yes, we have to care for the security of our nation. This means, among other things, of course that we have to fight terrorists. But we also have to build a world with more partners and fewer terrorists. Of course we have to stand against weapons of mass destruction -- but if we can, we have to do it in the context of building the international institutions that in the end we will have to depend upon to guarantee the peace and security of the world and the human rights of all people everywhere. (Applause).

You clapped when I made that comment about the United Nations and I am glad you did, but one of the challenges we face today is that all the international institutions in which we place such hope are still becoming, they are still forming. We have only really had a chance to make them work for a little over a decade. The European Union is not what most people think -- and at least I hope -- it will be in five, 10 or 20 years; it is becoming. The United Nations is not what I hope it will be in five, 10 or 20 years. There are still people who vote in the United Nations based on the sort of old-fashioned national self-interest views they held in the cold war or even long before, so that not every vote reflects the clear and present interests of the world and the direction we are going.

I take it almost everybody in this room supports what Prime Minister Blair and I did in Kosovo. (Applause). It was a clear and present emergency; you had a million people being driven from their homes. But in the end, even though we had all the Muslim world for it and most of the developing nations for it, all of NATO for it, we could not get a U.N. resolution because of the historic ties of the Serbs to the Russians. So we went in anyway and as soon as the conflict was over, the Russians came in and did a very responsible job participating with the United States in an international U.N. peacekeeping environment. Why? Why did that happen? Because the U.N. is still becoming.

You also see the same thing when we, the United States, do not contribute in my view as much as we should to international institutions. (Applause) You know I have a difference in opinion with the Republicans about whether we should be involved in the Kyoto protocol, the comprehensive test ban treaty, the international criminal court, and all these things, but these things stand for something larger which is our larger obligation to create an integrated world. You cannot have an integrated world and have your say all the time. And America can lead the world towards that, but we cannot dominate and run the world in that direction. There is a big difference. (Applause)

So, having said that, do we want to strengthen these institutions? Yes. Why? Because they contribute to an integrated global community. But if we cannot solve all the problems, what else do we do? One thing we know is that whenever possible the outcome is likely to be better if Great Britain and the United States -- and if the United States and Europe -- are working together. We have half a century of evidence to support that.

I am profoundly grateful for the partnership that we enjoyed in the years when I served as president -- in Bosnia, in Kosovo, in the Middle East, in Africa, in East Timor; in bringing China into the World Trade Organization and the community of nations; in trying to build alliances with Russia between the United States and Europe; all of the things we did together for global debt relief, and a hundred other issues; whenever we were working together the outcome was likely to be better.

I am profoundly grateful for Britain's involvement with the United States and with others in diplomatic efforts and where necessary in military ones. You were there when we turned back Slobodan Milosevic and the tide of ethnic cleansing which threatened every dream people had of a Europe united, democratic and at peace for the first time in history.

You were there in 1991 when the United States and the global alliance turned back Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait. When Saddam Hussein threw the weapons inspectors out in 1998 and we attacked Iraq, you were there. And when you were working towards peace in Northern Ireland, we were there. (Applause).

Whatever America did for Britain and Northern Ireland in the Irish peace process, you repaid 100 fold in the aftermath of September 11. Prime Minister Blair's firm determined voice bolstered our own resolve, his calm and caring manner soothed our aching hearts; and the British people pierced our darkness with the light of your friendship. In the aftermath of September 11th, we went to work against terror in a world rudely awakened to its universal threat, and much more willing to support the actions necessary to prevail.

I still believe our most pressing security challenge is to finish the job against al Qaida and its leaders in Afghanistan and any other place that they might hide. I would support even committing war forces to that. We have only about half as many forces in Afghanistan today that we had in Bosnia after the conflict was over and we were keeping the peace. I applaud Britain's commitment to finish the job in not only the conflict but to winning the peace, to staying in Afghanistan with an international force and with the kind of support necessary to make sure that we do not have the disaster that occurred when the West walked away from them 20 years ago. (Applause).

A few words about Iraq. I support the efforts of the prime minister and President Bush to get tougher with Saddam Hussein. I strongly support the prime minister's determination, if at all possible, to act through the UN. We need a strong new resolution calling for unrestricted inspections. The restrictions imposed in 1998 are not acceptable and will not do the job. There should be a deadline and no lack of clarity about what Iraq must do. There is no doubt that Saddam Hussein's regime poses a threat to his people, his neighbors and the world at large because of his biological and chemical weapons and his nuclear program. They admitted to vast stores of biological and chemical stocks in 1995. In 1998, as the prime minister's speech a few days ago made clear, even more were documented. But I think it is also important to remember that Britain and the United States made real progress with our international allies through the U.N. with the inspection program in the 1990s. The inspectors discovered and destroyed far more weapons of mass destruction and constituent parts with the inspection program than were destroyed in the Gulf War -- far more -- including 40,000 chemical weapons, 100,000 gallons of chemicals used to make weapons, 48 missiles, 30 armed warheads and a massive biological weapons facility equipped to produce anthrax and other bio-weapons. In other words, the inspections were working even when he was trying to thwart them.

In December of 1998, after the inspectors were kicked out, along with the support of Prime Minister Blair and the British military we launched Operation Desert Fox for four days. An air assault on those weapons of mass destruction, the air defense and regime protection forces. This campaign had scores of targets and successfully degraded both the conventional and non-conventional arsenal. It diminished Iraq's threat to the region and it demonstrated the price to be paid for violating the Security Council's resolutions. It was the right thing to do, and it is one reason why I still believe we have to stay at this business until we get all those biological and chemical weapons out of there. (Applause).

What has happened in the last four years? No inspectors, a fresh opportunity to rebuild the biological and chemical weapons program and to try and develop some sort of nuclear capacity. Because of the sanctions, Saddam Hussein is much weaker militarily than he was in 1990, while we are stronger -- but that probably has given him even more incentive to try and amass weapons of mass destruction. I agree with many Republicans and Democrats in America and many here in Britain who want to go through the United Nations to bring the weight of world opinion together, to bring us all together, to offer one more chance to the inspections.

President Bush and Secretary Powell say they want a U.N. resolution too and are willing to give the inspectors another chance. Saddam Hussein, as usual, is bobbing and weaving. We should call his bluff. The United Nations should scrap the 1998 restrictions and call for a complete and unrestricted set of inspections with a new resolution. If the inspections go forward, and I hope they will, perhaps we can avoid a conflict. In any case the world ought to show up and say we meant it in 1991 when we said this man should not have a biological, chemical and nuclear weapons program. And we can do that through the UN. The prospect of a resolution actually offers us the chance to integrate the world, to make the United Nations a more meaningful, more powerful, more effective institution. And that's why I appreciate what the prime minister is trying to do, in trying to bring America and the rest of the world to a common position. If he was not there to do this, I doubt if anyone else could, so I am very very grateful. (Applause)

If the inspections go forward, I believe we should still work for a regime change in Iraq in non-military ways, through support of the Iraqi opposition and in trying to strengthen it. Iraq has not always been a tyrannical dictatorship. Saddam Hussein was once a part of a government which came to power through more legitimate means.

The West has a lot to answer for in Iraq. Before the Gulf War -- when Saddam Hussein gassed the Kurds and the Iranians -- there was hardly a peep in the West because he was (fighting) Iran. Evidence has now come to light that in the early 1980s the United States may have even supplied him with the materials necessary to start the bio-weapons program. And in the Gulf War the Shi'ites in the southeast of Iraq were urged to rise up and then were cruelly abandoned to their fate as he came in and killed large numbers of them, drained the marshes and largely destroyed their culture and way of life. We cannot walk away from them or the proven evidence that they are capable of self-government and entitled to a decent life. We do not necessarily have to go to war to give it to them, but we cannot forget that we are not blameless in the misery under which they suffer and we must continue to support them (Applause).

This is a difficult issue. Military action should always be a last resort, for three reasons; because today Saddam Hussein has all the incentive in the world not to use or give these weapons away, but with certain defeat he would have all the incentive to do just that. Because a preemptive action today, however well justified, may come back with unwelcome consequences in the future. And because I have done this, I have ordered these kinds of actions. I do not care how precise your bombs and your weapons are -- when you set them off, innocent people will die. (Applause).

Weighing the risks and making the calls are what we elect leaders to do, and I can tell you that as an American, and a citizen of the world, I am glad that Tony Blair will be central to weighing the risks and making the call. (Applause). For the moment the rest of us should support his efforts in the United Nations and until they fail we do not have to cross bridges we would prefer not to cross.

Now, let me just say a couple of other things. This is a delicate matter, but I think this whole Iraq issue is made more difficult for some of you because of the differences you have with the conservatives in America over other matters, over the criminal court and the Kyoto Treaty and the comprehensive test ban treaty. I don't agree with (their positions) either -- plus I disagree with them on nearly everything: on budget policy, (laughter) tax policy (applause), on education policy, (applause), on environmental policy, on health care policy. I have a world of disagreements with them. But we cannot lose sight of the bigger issue. To build the world we want, America will have to be involved and the best likelihood comes when America and Britain, when America and Europe, are working together. I cannot believe that we cannot reach across party and philosophical lines to find common ground on issues fundamental to our security and the way we organize ourselves as free people. That is what Tony Blair could not walk away from, what he should not have walked away from and what we are all trying to work through in the present day. I ask you to support him as he makes that effort. (Applause).

If you will permit me, even though I am a retired politician (laughter), I would like to say just a word about domestic politics. United States and Britain cannot do good around the world unless we are good and getting better at home. You think about it. Much of the power that we can have grows out of the power of our example. We can't tell people to make a more integrated world unless they think we are making more integrated societies. Unless all of our children have a chance to get a decent education; unless we have balanced the demands for freedom and security; unless we have absorbed our immigrants in a way that is consistent with our values, and the elemental obligations we have for equal opportunity. We cannot do good abroad unless we are good at home. (Applause).

The ultimate case for the third way is that it works -- good values, good vision, good policies. We have eight years of evidence in the United States and now five years of evidence here that it works. (Applause). Opportunity for all, responsibility for all, a community of all people, good values. A vision where everyone has the chance to live up to his or her dreams, where we are growing together, not growing apart, where we are a force in the world for peace and freedom and security and prosperity. Where we shed ideas that don't work and embrace those that do -- and most of all go beyond the false choices that paralyze and make boring political debate. Going beyond neglect and entitlement to empowerment. Refusing to be told we have to choose between what's good for labor and good for business and say the best thing is if both do well. Refusing to be told that crime policy has to be about prevention or punishment and saying what works is both. That education has to be about excellence or equity; that health care has to be about access or quality; that environmental protection can only come at the expense of economic growth. All these things are factually untrue, but they dominate, control and paralyze the politics of countries all over the world. You have said no to that. The third way has said no to that and you got good results for doing it. (Applause).

If I might say, it worked pretty well in America too (laughter). We had a 30-year low on unemployment, we had a 32-year low in welfare roles, we had a 27-year low in the crime rate, all directly tied to policies we adopted. We had three years of surpluses in the budget for the first time in 70 years and the biggest increase in aid to university students in 50 years. And the thing that means the most to me is the comparison of our economic recovery with the Republican recovery of the 1980s. They had 14 million jobs and only 70,000 families move out of poverty. We had 22 million jobs -- 50 percent more -- but 7 million moved out of poverty, 100 times as many. (Applause).

That is the importance of politics of choices. I understand now that your Tories are calling themselves "compassionate conservatives." (Laughter). I admire a good phrase. (Laughter). I respect as a matter of professional art adroit rhetoric, and I know that all politics is a combination of rhetoric and reality. Here is what I want you to know. The rhetoric is compassionate, the conservative is the reality. (Applause).

Let me be serious a minute. Our politics are based on ideas -- a desire to increase opportunity and to strengthen community. And we know we are not always right, even though everybody hates to admit that, we are not. So we have to operate on the basis of evidence, and be open to argument. Their politics is based on ideology and power, and they don't like evidence and argument very much. My wife, the junior senator from New York, says that Washington sometimes seems to have become an evidence-free zone. They operate by attack. But at some point you've (got) to look at the evidence.

In my country evidence shows that their ideology drove them to adopt an enormous tax cut heavily tilted to wealthy Americans. I ought to be happy, I am one of them now! (Laughter) But I am not. Why? Because we adopted a tax cut in America before we had a budget, before we knew what our income was going to be, before we knew what our expenses were going to be, before we knew what our emergencies were going to be -- and Sept. 11 turned out to be quite an emergency. So we went from a decade-long projected $5 trillion-plus surplus to having it go away. We went from having the money when I left office to take care of the Social Security retirement cost of the baby boom generation, and half of the medical costs of them, to having it go away and using those trust funds to pay for tax cuts for people in my income group. Did the evidence support it? No. But the ideology did.

They declared war on all my environmental regulations, they even tried to relax the standard on how much arsenic we could have in the water. The Democrats stopped them, and besides, there was a very small constituency for more arsenic in the water in America! (Laughter and applause). So then they went on to other things. To try to make the deficit look smaller, they tried to refigure the accounting and requirements to raise the cost of student loans at a time when college scholarships were going up. The Democrats stopped them and besides they found that even among conservatives there was hardly anybody who thought that college ought to be more expensive in America. But their ideology drove them to it and I could give you example after example after example.

I say this because you should be proud that you have stayed with what works, and you should stay with it. You should know that you have to fight every day to explain what you are doing. You have to always keep your ears and eyes open to find the errors that you make, and you must always be the party of change. But you have to keep going, because the rest of the world looks to you. When people are insecure, they often turn to the right because of the rhetoric, because of the ideological certainty, because if we show feeling sometimes people confuse compassion with weakness -- a mistake that the prime minister has taken great care to avoid here, and I appreciate that. So we have these election reversals in Europe. And the election was so close in America that they won it fair and square -- 5 to 4 at the Supreme Court. (Laughter).

We should actually be glad, though, because there were seven Republicans and only two Democrats on the Supreme Court -- and two of those Republicans (God bless them, they will be rewarded in heaven), they actually took the decision that we should count votes when the American people vote, and I appreciate that. (Applause). A lot of the retrenchment, the fear of voting, was understandable in Europe but now it is beginning to come back: Prime Minister Persen in Sweden re-elected, Chancellor Schroeder reelected in Germany. But all over the world constitutional democracies are now teetering on a 50:50 basis. In every place one party has become the repository of hopes and the other has been the responder to fears.

New Labor, this government, has not allowed that dichotomy to occur in Great Britain. Don't you ever do it; keep working for change and keep telling people strength and compassion are two sides of the same coin, not opposite. (Applause).

I would like to close with this simple idea. All of the hopes that I have for my daughter's generation, for the grandchildren I hope to have, for all of you who are younger than me and, unlike me, still have most of your lives ahead of you, rest upon our ability to get the world to embrace a simple set of ideas -- that we must move from interdependence to integration because our common humanity matters more than our interesting differences and makes the expression of those differences possible; because every child deserves a chance, every adult has a role to play and we all do better when we work together.

That is why we must build the institutions that will help us to integrate, that is why we must stand against the threats, whether they are from weapons of mass destruction, terrorists, tyrants, AIDS, climate change, poverty, ignorance and disease which would tatter this world and prevent us ever from coming together as one.

That is why we must never forget people at home, even as we work for those around the world; why we must want the same things for the children of Britain and America; of the Greeks and the Turks in Cyprus; the children of the Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda; the Colombian children so beleaguered by the narco traffickers and the terrorists there; the children of the East Timorese and the Indonesians in the Pacific; the children of the Muslims, the Hindus and the Sikhs in Kashmir and Gujurat; and maybe some day even for the children of the Palestinians and the Israelis in the Middle East. (Applause)

I ask you to think of this work as the true and ultimate third way, going beyond the exclusive claims of old opponents to a future we can all share; going beyond the fears and the grudges, the fights and the failures of yesterday's demons to a truth we can all embrace. The third way in the end must lift our adversaries as well as our friends, the children we must never see because they are too far away, as well as those just under our feet. If we do it, the 21st century will be the brightest time the world has ever known, and if we do it, it will be in no small measure because when you were called to meet the great challenge of the new millennium, you responded. Thank you, and God bless you. (Applause).

Shares