Merle Haggard has given up on the idea of a sound check. We're in his tour bus on West 43rd Street in Manhattan, in front of the Town Hall theater, where he will perform in a few hours. President Clinton is in town, and the Merlemobile is being shooed away by New York's finest to make room for the motorcade. Traffic is moving in slow motion; finding another place to park this hulking vehicle could take all night.

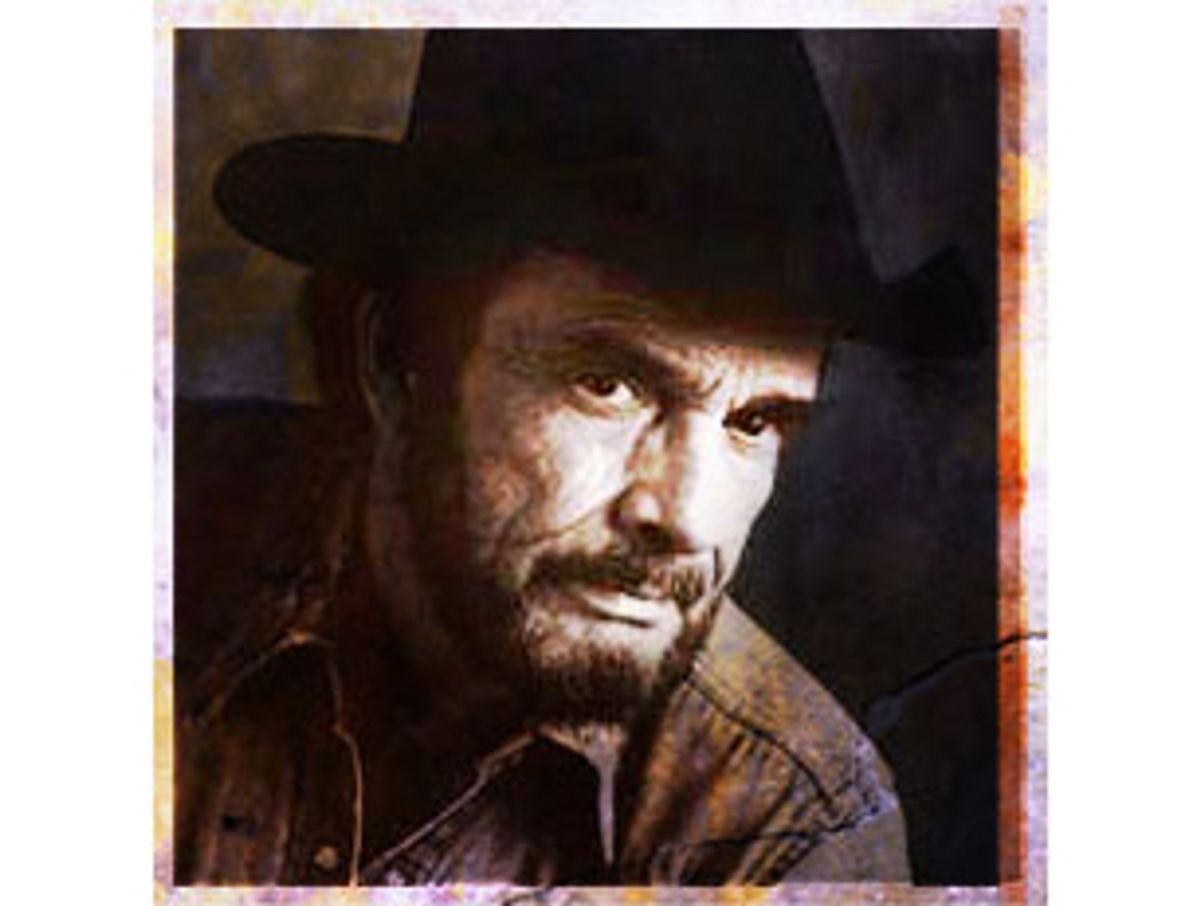

Not that Haggard is concerned. He's been in this business for 35 years and has 41 No. 1 country songs on his risumi, including the classics "Mama Tried," "Think I'll Just Stay Here and Drink" and the notorious "Okie From Muskogee." He specializes in writing deceptively upbeat songs of longing -- for a woman, for the bottle, for the past, for the road -- that are inspired by his rough-and-tumble life and the struggles of the rural working class. His singular mahogany voice and synthesis of elements of the work of artists from Bing Crosby to Lefty Frizell continue to thrill listeners and influence musicians of every persuasion. He's a living legend of country music; he don't need no stinkin' sound check.

Dressed in jeans, sweat shirt and pork-pie hat, Haggard sinks back into the bus's beige leather banquette as he talks about his many projects this fall: HarperCollins published his memoir "My House of Memories" last month; he has a new two-CD set, "For the Record: 43 Legendary Hits" out from BNA; and he's winding up a cross-country tour. At 62, Haggard shows no signs of slowing down. Of course, his bankruptcy in 1992, due to a combination of reckless living and careless money management, gives him little choice. "It's not really what I had in mind for this point in my life. But we seem to be getting hotter," he says over the goofy banter of the members of his entourage who are along for the ride. ("Maybe we should ask Clinton to play with us tonight. He could play the whore-Monica.")

Recording the CD, a collection of new versions of many of his greatest songs, was a humbling experience. "An analogy might be if Babe Ruth had lived as long as I have and then tried to repeat a great moment at the plate," he explains. "It's hard to recapture." It's a mixed bag, Haggard admits: "Some of the songs are better, some not as good, some just different." Tracks such as "Misery and Gin" seem richer coming from an older, wiser man; others, including "Sing a Sad Song," don't seem to suit the depths of his mature voice.

There are also duets with Willie Nelson and Brooks & Dunn, and, despite his vocal aversion to most contemporary singers, he teams up with Jewel for "That's the Way Love Goes." "I was on tour when she recorded at my studio, so I didn't even meet her until we performed together at the Country Music Awards" in September, Haggard recalls. "It was a pleasant surprise. She's a real nice girl. I think we'll be doing more together."

Suddenly, Haggard is craning his neck, scanning the lanes of stationary cars. "Is that Kris' limo up there?" he asks. (Kris Kristofferson is the opening act tonight.) "Let's go see if he wants to come back here."

"I already asked the driver," one of the gang pipes up. "He said he didn't want to."

"Not the driver, Kris!" exclaims Abe Manuel, an all-around musician and longtime member of Haggard's band, the Strangers.

"He didn't seem to speak English."

"Who, Kris? He writes in English," Manuel says of the songwriter, with mock bewilderment.

Haggard is much amused by the exchange. He rocks back slightly as his creased face stretches into a huge grin. Then he turns to me: "You see what it's like around here?" he deadpans, his eyes a heart-stopping cobalt blue. "The only way we can keep from going crazy is to try to totally confuse one another."

His wrinkles are not all of the "laugh line" sort, to be sure. A mix of "The Grapes of Wrath" and "Rebel Without a Cause," with some

Elvis Presley-style brilliance and excess mixed in, Haggard's life has been a series of dramatic highs and lows. "My House of Memories" more or less picks up in the 1970s, where "Sing Me Back Home," his first memoir, left off. "I've had a monstrous 20 years since that first book, just career-wise," he marvels.

Haggard grew up in a converted boxcar outside Bakersfield, Calif. His parents were transplants from Oklahoma, like many who moved West during the Depression, but Merle was born in California. (He has lived there almost all of his life, shunning the Nashville scene.) After his father died when he was 9 years old, Haggard was constantly in trouble: running away, hopping trains, skipping school, joyriding and committing other minor crimes. The stories of his many escapes from the authorities might be the best parts of "My House of Memories." He finally landed in San Quentin for a botched restaurant robbery when he was 20.

Prison shocked him into living on the straight and narrow. "Going to prison has one of a few effects," he explains. "It can make you worse, or it can make you understand and appreciate freedom. I learned to appreciate freedom when I didn't have any."

When he was paroled in 1960, he became a regular on the stages of Bakersfield, where the local oil- and cotton-field workers were enthusiastic country-music listeners. "Sing a Sad Song" hit the charts in 1963, and he signed with Capitol soon after. He had five No. 1 country songs by the end of 1968, including "The Fugitive," "Sing Me Back Home" and "Branded Man." Then in 1969 came the controversial song that secured his stardom: "Okie From Muskogee," an anthem defending traditional values in the age of hippies and free love. "The song confused everybody," Haggard remembers. People assumed the song reflected his views, but "that was just the way the song went together. It wasn't necessarily me in that song."

"Okie" struck a powerful chord with many Americans. The first time Haggard played it was at an Army base. "People came up on the stage, grabbed the mike and said, 'We don't want to hear anything else until we hear that song again.' We thought an Army base wasn't a fair trial, so the next night we played it in a concert hall. People came over the orchestra pit and onto the stage. It was kind of scary -- Beatlemania was going on at the time and we didn't know how to handle that kind of response." "Okie" went double platinum in 120 days, and Haggard went on to record more hit songs than any other country performer except Conway Twitty.

The smooth success of his career always contrasted with his rocky personal life. There have been four divorces (including one from Bonnie Owens, once Mrs. Buck Owens, who still performs with Haggard), drug addictions, high-stakes gambling and ill-fated investments. "My House of Memories" describes in detail the hedonistic years Haggard spent living on a houseboat on Lake Shasta during the 1980s. By the early-'90s, he had burned through $100 million. He received his bankruptcy papers at the hospital the day his son Ben, now 6, was born.

Today he is on his way to financial health and says he is finally living at peace. The habits of his wild years are nowhere to be seen on the ranch outside Redding where he lives with his fifth wife, Theresa, and their children, Ben and 9-year-old Jenessa. Instead of chasing women and throwing parties, Haggard spends his free time with his family at one of the nearby creeks, fishing for bass. "After we take care of all our chores, and we have about 200 acres so there's a lot to do, at about 4 we turn off the phone and go fish until dark. We usually have our supper down there by the creek. It's our tradition."

Looking back on the old days wasn't easy for him. "Writing a memoir is like going to a psychiatrist," he says. "The emotions are still sensitive. You uncover these memories and the emotions are just lying there, naked." Indeed, his guilt and regret are clear in the memoir's passages about his children from previous marriages, who he doesn't think got enough of his affection; his mother's memories and fears that were only revealed to him in a handwritten autobiography discovered after her death; and his loss of control over his life due to drugs and drink, which allowed others to take financial advantage of him.

Sound like the screenplay for a movie? Robert Duvall thinks so. He owned the film rights to Haggard's life story, but they expired recently. Now he's trying to buy them back. However, "the deal he's offering isn't that good, and I'm just not in the market for deals that aren't that good," Haggard says. "It's my life and I don't particularly care if the story is told."

Haggard stares out the window for a moment, seeming not to hear my questions about his opinion of contemporary country music. The bus inches forward. Did I say something wrong? I think about his recent encounter with two pushy reporters from the Star tabloid at his ranch -- Haggard got fed up with their prying and escorted them off his property, mid photo session -- and hope I am not about to be ejected from the bus.

Finally he turns and quips: "Someone said to me today they really like the commercials on the radio --they let you know when one song stopped and another started." (Phew, I'm safe.) "I hear a lot of blandness, a lot of songs about things with no point. In Redding, I'd rather listen to the rock 'n' roll station than the country station. At least on the rock station you get good rock." The last "spectacular" thing he heard on the radio, he says, is "Unforgettable" by Natalie Cole, one of his favorite singers.

Particularly rankling for Haggard, who is passionate about the history of music, is contemporary country's lack of roots. "I'm not sure today's country comes from the same place mine does. It comes from technology, not from the labor camps or cotton fields that I identify with," he says. "When I got started in this business, you started with the art form. Then they'd say they want you to record. Now they pick you because you look like Hank [Williams], and they add the music. But you can't take a guy and make him into a Hank."

Haggard thinks pop-country music -- which has produced megastars like Shania Twain and Garth Brooks -- is on its way out. "People are being force-fed new country. They haven't had a choice. Only one type of music is getting played. But I think a change is about to occur. Music fans are bored to death," he argues. "It's like Harry Potter. No one expected that to be so successful. But people grabbed on to something different." Haggard, too, seems ready for something different. "The music and the crowd's response are what make this fun," he says as the bus rounds the corner of Sixth Avenue and 44th Street.

Yet of all his songs, he says the one that best describes his current position in life is "Footlights," a 1978 number about a burned-out musician. He wrote it after he had to play a concert five minutes after hearing that Lefty Frizell, one of his idols, had died.

I'll try to hide the mood I'm really in

And put on my old Instamatic grin

Tonight I'll kick the footlights out again.

"I'm getting to the point where it's time to start thinking about not being able to make a living the way I have for 35 years," he says as the bus parks in a once-in-a-lifetime empty stretch of curb not far from Virgil's, the barbecue restaurant where he will have a quick dinner before taking the stage. "I wasn't investing until recently. Now I have a new family I wasn't planning on. You know they say if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. Well, my plan was to live on a houseboat and drink and party my way out. I quit drinking and smoking not because of pressure from outside but because of the kids and new responsibilities. I'm glad I did it. I think I'm more in charge now."

He'd like to get into business -- the "other side of the camera," as he calls it. But that's later. Right now he's looking forward to getting back to his ranch and his family. "I like to listen to the creek run."

Shares