British actress Julie Walters, first seen by American audiences in "Educating Rita," works in an utterly singular style that might be called Method caricature. Often outfitted in shellacked wigs and dowdy clothes, Walters looks as though she might be getting ready to do a sketch on "The Carol Burnett Show," and her broad take on her characters' accents and patterns of speech wouldn't be out of place in sketch comedy. But by bombarding us first with the physical trappings of the women she plays, Walters gives us time to get used to their eccentricities.

After a few minutes, they don't seem so strange anymore, and we're freed to witness Walters getting down to her real work: the emotional revelations that she accumulates in precise, sometimes minute layers. Unfortunately, the films in which she has done her best work -- as the working-class madam in "Personal Services," the repressed petit bourgeois in the horrifying "Sister, My Sister," the terminally ill woman preparing her weak husband for her inevitable death in "The Wedding Present" and the English housewife who has a disastrous affair with a young boarder in "Intimate Relations" -- have barely been blips on the radar in this country.

"Titanic Town," directed by Roger Michell ("Notting Hill," "Persuasion"), may stand a better chance. It's being presented by Sony theaters in the series of films that earlier this year brought us "Judy Berlin" and "Croupier." In some ways it's not a very good movie. Michell, working from Anne Devlin's screenplay (based on a novel by Mary Costello), tries to mix comedy and tragedy and the uneven result only throws into relief how well Walters routinely brings off the same unstable mixture. But the movie has an exciting subject -- the true story of an Irish Catholic housewife who set out to stop the "troubles" in Northern Ireland -- that holds your interest even as the direction falters.

There's a terrific opening sequence. Bernie McPhilemy (Walters), her perpetually ill husband, Aidan (Ciaran Hinds), and their four kids move into a new housing estate in Belfast. That night, their relatives and friends gather for a housewarming and Michell gives us a familiar, sentimental scene: the family gathered in the parlor singing "Danny Boy." And then he does something that undercuts the whole cozy: Cutting to the McPhelimys' new front yard, the camera pans along until it picks up an armed British soldier, camouflage darkening his face, lying with weapon at the ready in the family's flower bed.

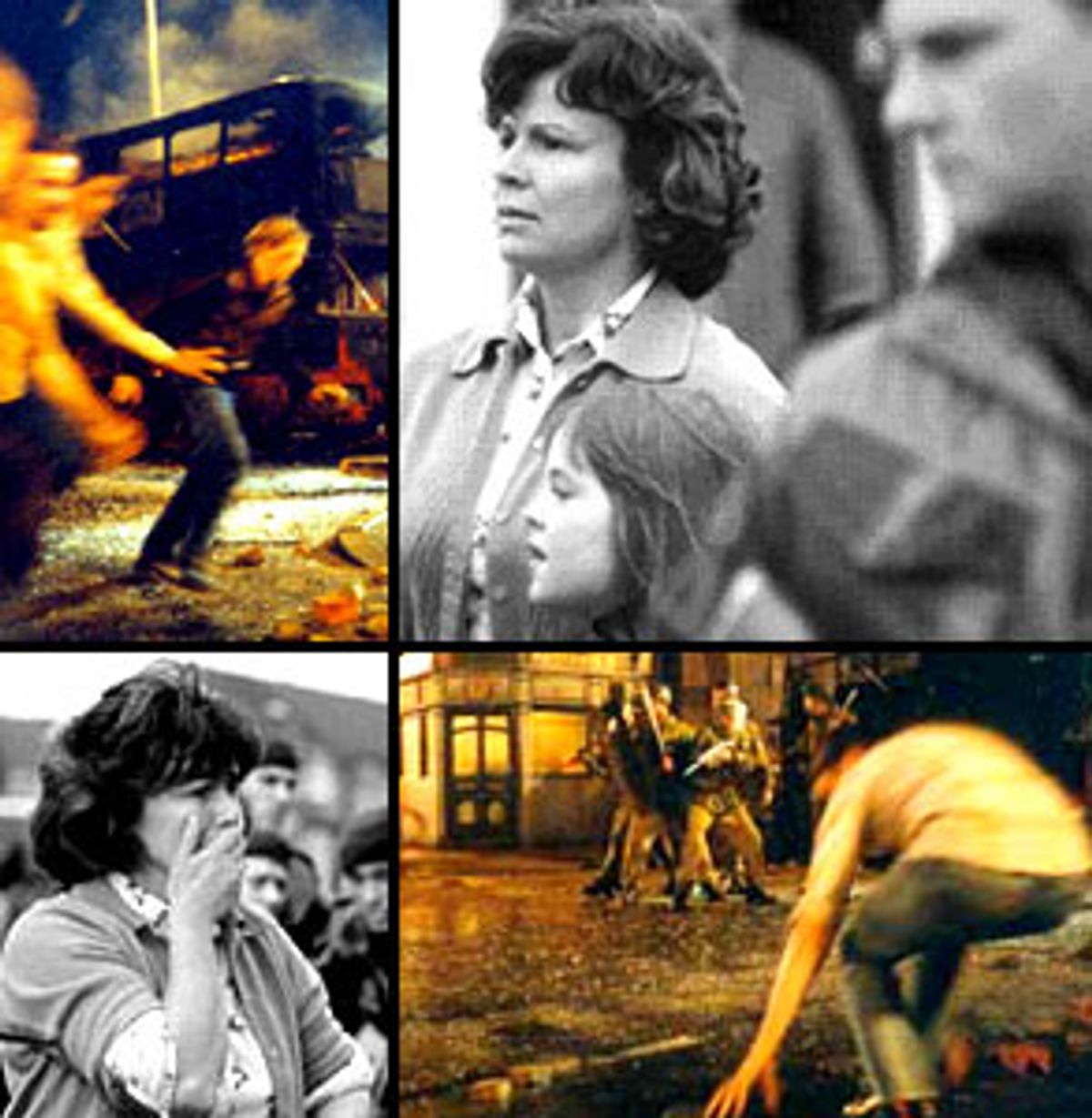

There are other moments, too: People go about their shopping on rubble-strewn streets while soldiers maneuver from hiding post to hiding post; passengers calmly disembark from a bus as rock-throwing kids attack the vehicle and then, after a drink at the pub, continue on foot while the charred hulk of the bus burns. In all of these Michell gives us violence as a fact of life so accepted it's nearly unnoticed -- except that Bernie can't ignore the helicopters circling overhead at night, the wounded IRA soldier banging on her door for shelter, the neighbor shot in the face by a rubber bullet as she stands by her window.

So she sets about trying to secure a promise from both sides that there will no gunfire during the daytime, attempting to restore some semblance of everyday safety to her family's existence. Taking the position of talking to anyone who'll listen, she encounters the wrath of neighbors who think she's selling out to the British, as well as the suspicion of the British that she's fronting for the Irish Republican Army.

What's exasperating about Bernie is inseparable from what's admirable about her: her disdain for politics. When the IRA tells her it'll agree to a cease-fire under certain conditions, she reports the conditions to the British, not even thinking that she's rattling off a list of impossible demands they've heard countless times before. I don't know that I've ever seen a performance that captures as well as Walters' does the kind of naive indignation of people who venture into a politically fraught situation with nothing but their implacable sense of what's right and what's wrong.

When Bernie is verbally attacked by neighbors, you can almost feel her spine stiffen as her voice rises to a high, choked pitch. Defending her position is, for Bernie, inseparable from defending herself, and you can feel her shock and hurt as she tries to assure her detractors that she isn't taking sides. What Bernie McPhelimy did, garnering scores of signatures on a petition supporting peace, was not only brave (her house and family are, in one tense scene, attacked by a gaggle of her pro-IRA neighbors) but a triumph against dangerous odds. But Walters isn't interested in striking heroic poses. She refuses to shortchange the blinkered, headstrong parts of Bernie, refuses to make the character more likable than she is. It's a fully honest portrayal without a trace of condescension in it, and a challenge to the audience. Take this woman as she is, Walters might be saying, or not at all.

Unfortunately, we have to take the movie as it is as well. Michell is a serviceable director, but he lacks urgency and focus. He gets by on the tragedy of Northern Ireland rather than the sharpness of craft. What he does right -- like that opening scene that ends with the glimpse of the British soldier, or the truly unnerving black-humored final shot -- is nearly sensational. But the movie never accumulates the force of other films that have dealt with the troubles.

I'm thinking especially of Terry George's fine and too little seen "Some Mother's Son," which starred Helen Mirren and Fionnula Flanagan as two mothers on separate sides of the Irish question whose sons are both part of the IRA hunger strikes led by Bobby Sands. That film also featured imposing, ruggedly handsome actor Hinds, as an IRA official. Here, as Bernie's husband, Aidan, Hinds looks shockingly different. In horn-rimmed glasses and ugly sweaters, his long, dark hair limply plastered to his forehead as if he were in a perpetual state of clammy sickness, Hinds suggests a withered heft, like an enormous balloon slowly deflating. Hinds, in his way, is as unsparing as Walters. Aidan is an essentially weak man whose fear for Bernie keeps him from lending her the support that a wife might expect of her husband. But the role doesn't do much for Hinds. The script never digs as deep as it should into Aidan's character, and he comes to seem a sweaty albatross around his wife's neck.

Nuala O'Neill does much better as Bernie and Aidan's daughter Annie. She has to contend with both the typical teenage embarrassment with one's parents and real resentment toward her mother for the danger she's putting them in. Physically, O'Neill is perfect for the role. She's touching in the manner of girls who blossom while the baby fat is still visible on their cheeks, making them seem both womanly and childishly vulnerable at the same time.

She and Walters play a fine scene in which all of Annie's resentments toward her mother come pouring out, and the confused feelings she shows toward a university student (Ciaran McMenamin) she falls for are touchingly real. But she's let down by Devlin's script and Michell's direction, which are confusingly unclear about the young man's intentions toward her.

There are so few movies today that offer the immediacy of topical subjects that even this muffled, uneven picture can make you feel more connected to a larger issue than most movies do. At its best, it's a dark comedy of quotidian catastrophe. But the underlying tragedy never cuts as deeply, as woundingly, as it should.

Shares