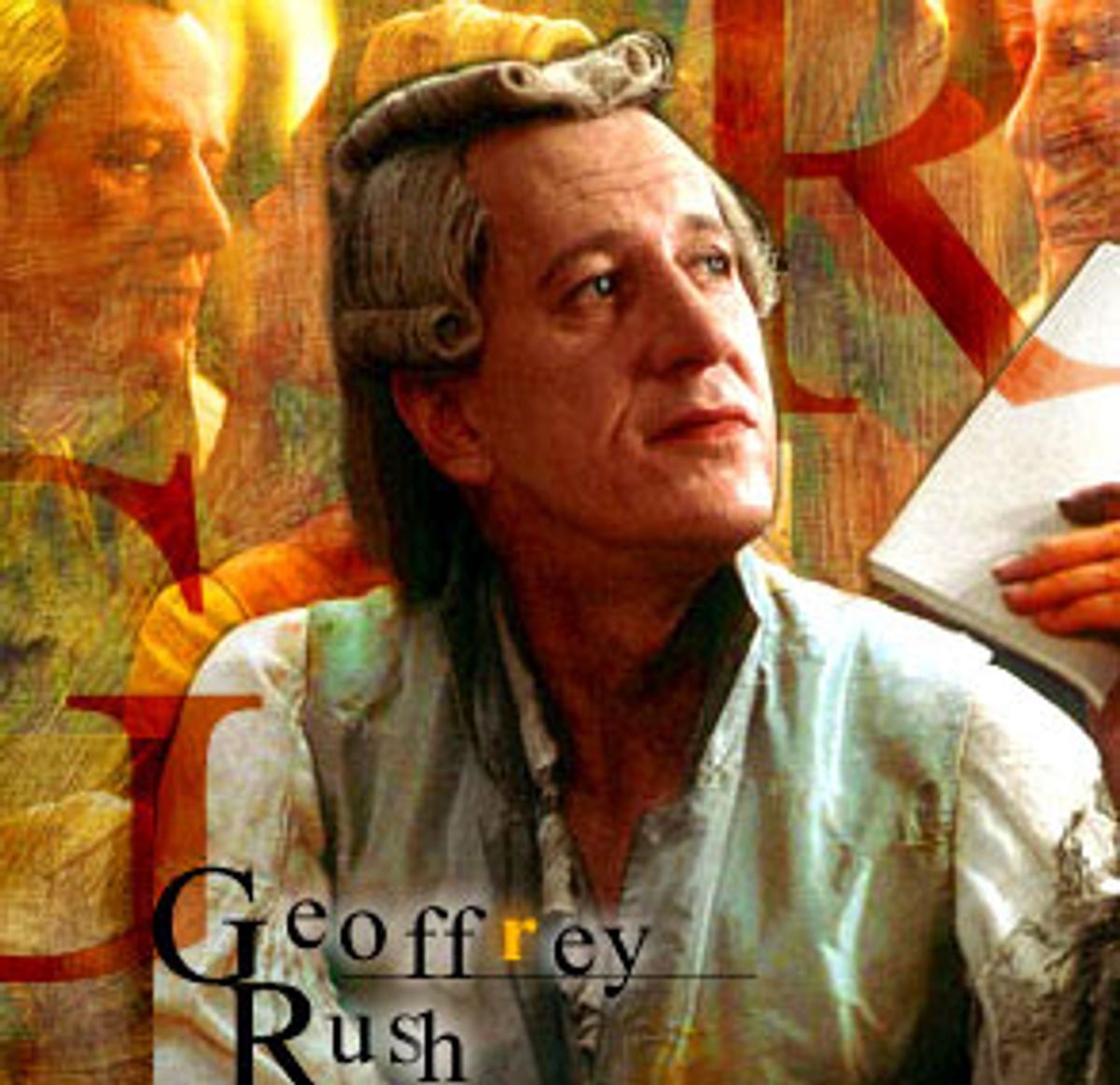

To quote Doug Wright's screenplay, the first aural and visual impressions you get of the Marquis de Sade in "Quills" are a "reptilian" eye and a voice at once "mellifluous" and "low." His hand sports an amber ring containing "an arachnid trapped in stone." Yet from the get-go, Australian actor Geoffrey Rush imbues this ominous figure with a nihilistic joie de vivre that's both infectious and unsettling. It's crucial to the complexities of Philip Kaufman's exuberant, rending tragicomedy that the man who prances through the intersection of pleasure and pain remains a life force and an art force. Rush comes through with flying colors -- albeit ones ranging from gore-red to dung-brown. He gives Sade an anarchic erotic glee that's inseparable from his theatrical imagination and volcanic urge to write. It's fitting that Rush used as a major source book Francine du Plessix Gray's biography "At Home With the Marquis de Sade: A Life," which emphasizes Sade's seductive dance with surrogates for his distant mother, while Kaufman relied more on Neil Schaeffer's "The Marquis de Sade: A Life," which pivots on the Marquis' vain attempt to find a moral and intellectual authority to substitute for an absent father. Thanks to Rush and Kaufman (and, of course, Doug Wright), "Quills" has a quivering blend of yin and yang.

With a kind of anti-noblesse oblige, Rush's Sade uses his superior wit to ensnare everyone who surrounds him at the Charenton insane asylum into fatal or near-fatal flirtations with his perverse worldview. That includes the liberal Abbé de Coulmier (Joaquin Phoenix), who tries to run Charenton as a City of God, and Madeleine Leclerc (Kate Winslet), the innocent laundress who helps Sade smuggle out his writing.

Ironically, he doesn't need to spin his twisted wonders on his enemy, physician Royer-Collard (Michael Caine), who answers Napoleon's call to squelch the writer's blasphemous and profane work. Royer-Collard, a righteous hypocrite, is already a more dangerous sadist than Sade is.

Kaufman has referred to the four leads as a quartet, and they are matched brilliantly. Caine brings subtle notes of savvy to his Machiavellian doctor. Phoenix has never been sharper or more commanding, while Winslet is gutsy, intuitive, alluring; together they're unsentimental heartbreakers. Yet Rush registers as their fellow player and also as their mad conductor, whipping them and the audience into unpredictable crescendos of laughter, snorts, gasps and tears.

Amid general acclaim, some critics have voiced surprise at Rush's wholehearted submission to the script's combination of depraved vaudeville, Grand Guignol and even grander tragedy. But you can see elements of Sade's shrewdness, furtiveness and unpredictable genius in the body of film work Rush has built from his shattered concert pianist in "Shine" and his master spy in "Elizabeth" to more lowdown parts like the ruthless thrill-park impresario in "House on Haunted Hill" and the mad scientist named Casanova Frankenstein in "Mystery Men." I think Rush was at his best as theater-owner Philip Henslowe in "Shakespeare in Love." It allowed him to wed his appetites for high and low culture -- he says he loved being a character dressed in a suit that made him look like a stink bug, who ordered no less than William Shakespeare to cut to the chase, with prose. "Quills" permits him to vent the same iconoclastic impulse on a riskier stage -- while demonstrating the heartbreaking human sacrifice exacted by the need to create art.

I interviewed Rush two weeks ago, on the morning of the movie's premiere in director Kaufman's home city, San Francisco.

I first saw the movie with eight people spread out across a large screening room; everyone was laughing to themselves but nobody could hear anybody else. It turned out everybody loved the movie and thought it was hilarious.

It kicks up with a bigger crowd; you get big surprise laughs. You know when audiences go "Whooaaa!" and then think, "We all just did that together and we didn't think we were going to" -- especially with a film that's presumably going to be about sadism. I think they're delighted to discover that it's about sadism in many different forms -- including the ways a society can be sadistic. At the beginning, when you see rough hands on a delicate young woman's neck who is breathing heavily, you think, "Oh, hang on, we're watching something in a kind of 'porn-ish' genre." When they find out what's really happening, people go "Ohhh!" It's scarier than the end of the "Jurassic Park" ride at the Universal tour; it's like the kind of nightmare where you're falling, falling, falling. Within the first two minutes of the film Philip Kaufman is already messing with your mind. I love that.

Phil and his team shot all the location stuff -- they managed to find French-style architecture in the environment of Oxford, England -- before I even got on the film. I felt like the bridegroom that showed up extremely late. But Phil was in such glee, so wired up and excited -- "We have the camera, here's the guillotine blade, let's put the neck of the audience on the block" -- I thought it was just brilliant.

Did Phil see you play the character of Casanova Frankenstein in "Mystery Men"? Casanova Frankenstein wouldn't be a bad nickname for the Marquis de Sade.

[Laughter] Well, curiously enough, that film got cut so badly that Lena Olin [the star of Kaufman's "The Unbearable Lightness of Being"] was edited out of the movie. We had four big scenes together which would've given you an idea of why he was called "Casanova Frankenstein" -- high-comedy love scenes that were also suitably cheesy, to fit the comic book form. What appealed to me about the script of "Mystery Men" was this great oxymoron of a name. The moment you say, "I'm playing Casanova Frankenstein," you think "I can see two big dimensions in this character, just for starters." [Laughter] But -- no regrets, you know. It was an absolutely wonderful experience.

In your major movie roles, you've often played characters who are obsessed, like Javert in "Les Miserables." In fact, Javert and "Shine's" David Helfgott and now Sade, lurk around prisons or asylums or, for that matter, theaters, and have twisted relations with authority. From the outside, this body of work has an oddball coherence to it.

But in my head I think, well, I've played a theater owner in the mercantile world of the Elizabethan theater ["Shakespeare in Love"]; I've played a cop, which is very unlike me, in "Les Miserables"; and I've played a libertine who happens to be in an asylum. What makes them coherent for me is that the story being told in all of them is allowed to emerge out of small isolated environments.

You've talked about sharing a sensibility with Phil Kaufman, despite coming from different countries, cultures and generations. I wonder if it has anything to do with him continuing to make films the way he and others did in the late '60s and early '70s.

The films the American studios made in that era did have a big impact on me in Australia. When I was first leaving high school and going to university, it was during those three or four years of extraordinary change in pop culture that are covered in the book "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls." In my last years of high school, it seemed that everyone was trying to remake "The Sound of Music": They did "Star"; they did "Dr. Dolittle"; they did "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang." And they almost brought the studios to their knees. But then suddenly, in 1969, I was smack in the middle of that generation that would go to see Alan Bates' penis in "Women in Love" and Olivia Hussey's breasts in "Romeo and Juliet." And I discovered that people like Antonioni and Fellini, great Italian auteurs, were still releasing major work. All that was obviously an influence on me.

I was torn between this great passion for the psychology of American films -- through John Garfield and Brando and Shelley Winters, up to Robert De Niro -- and the classics I was doing onstage. I started working professionally in 1971. Throughout my whole first decade as an actor, when I was studying in Paris and stuff, I'd follow an actor like Dustin Hoffman -- who I knew was from the New York theater scene -- do "The Graduate" and then maybe a year later "Midnight Cowboy" and then "John and Mary" and then "Little Big Man." And DeNiro, a bit later, in "Mean Streets" and "Taxi Driver" and "The Deer Hunter" and "Raging Bull." And they were phenomenal, luminous, highly sculpted, anti-heroic but large figures -- which is so unlike what I was doing on stage.

Well, you're an amazing student of film acting -- you list "John and Mary" as one of Dustin Hoffman's credits, and that's probably his least remembered movie.

But I did get the order right, didn't I? That's how his films came out.

My point exactly!

People used to say to me, "Oh, you'd never be very good in films; you're too big." I felt like I came from a generation of Australian actors that was still influenced by an English tradition of theater, perhaps because of a certain heritage of language. But then we started to redefine ourselves in Australia over the course of a couple of decades, finding our own particular voice and expression within the classical repertoire.

Most recently in the theater -- say in the last 10 years or so -- I've done things like Gogol's "The Government Inspector," and "Diary of a Madman," based on the Gogol short story. I've been Astrov in Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya." I've played a scabrous cockroach con artist in Ben Jonson's "The Alchemist." I've played lots of Shakespearean clowns, idiots, outsiders, sleazebags. I sense a huge dimension in that repertoire, but those roles are my strong suit.

It seems to me that I'm more a figure in a landscape in wide shots than I am a mind to watch at work in long, lingering close-ups. Do you know what I mean?

Yes, but I don't agree. In your films, and especially in "Quills," you often are a mind to watch at work in close-up.

Yeah? I don't know --

Or maybe in movies you show a willingness to externalize the internal stuff so that it's immediate and unselfconscious -- you kineticize the characters.

Yes. Well, that's from my training with the French mime, Jacques Lecoq. That was about approaching performance through a study of movement and your own distinctive clowning, your own distinctive buffoonery.

The list of your stage roles suggests a strong sense of the absurd. Re-setting Shakespeare and the classics in a modern, absurd universe revitalized many companies in the '60s and '70s.

Yes. The other thing to mention is that I started out as a repertory actor and for three years had to earn my stripes playing tiny parts, like eccentric, drunken innkeepers. And then, having done that, I played Snoopy. That was my first big break in a company, playing a lead.

Snoopy -- that's ideal. In many of your roles you convey a childlike playfulness -- including, in a thoroughly debauched way, your Marquis de Sade.

Yeah, performance-as-play is what I'm interested in. It's funny. Fifteen years ago I had created and directed this play called "The Small Poppies" about three 5-year-olds starting out at school. And I performed in it again right after "Quills." It was good for me to do something that was absolutely simple and pure.

One thing I like about my career is its dichotomies. For example, after I did "Shine" and [the Australian political spoof] "Children of the Revolution," I felt, "God, all I've been doing are vulnerable characters." So that became a big part of running with the idea of doing Javert in "Les Miserables" [the Bille August film, starring Liam Neeson as Jean Valjean]. I wanted to test the dimensions of my possibilities, and not feel as though I were limiting myself by playing only vulnerable men. In my youth I was always referred to in every review I ever got as "gangly," no matter what I did. "Gangly Geoffrey Rush." I'm 5-foot-11-and-a-half, and have always been pretty thin. So I had that desire to find whatever greatness I had in my verticality. Where is the steel rod? You know what I mean? What strength do you have?

When the stage director Neil Armfield, who directed me in "Diary of a Madman" and many other productions, said, "I want you to play Astrov in 'Uncle Vanya,'" I responded, "You know, it's not very funny." I had pretty well defined myself in the comedy repertoire. And he said, "Well, I think there's a melancholy drunken misfit quality in you that could be looked at." And it was great.

And I bet you found that "Vanya" actually is a funny play.

Absolutely, absolutely. But it's kind of deep, rich, poignant and disturbing comedy. And sometimes just loopy, you know. Chekhov's characters go through bouts of letting off steam.

How do you go from, say, Chekhov or Gogol, to playing the Vincent Price role in "House on Haunted Hill"?

"House on Haunted Hill" for me was a way of dipping my toe into the shallow end of American culture. [Laughter] But look -- in some ways it's all kind of haphazard.

Did Phil approach you for "Quills," or did you go after it?

My agent rang and said, "I've got this script about the Marquis de Sade." Phil and I had lunch and chatted about things we liked and felt an unspoken kinship. It's the sort of like-mindedness that comes from having the same curiosities. After you meet someone like that, in your mind you check him out and you say, "Wow, he's done 'The Right Stuff,' 'The Unbearable Lightness of Being' and 'Henry and June.'" Then you find out he co-wrote 'Raiders of the Lost Ark' and 'The Outlaw Josey Wales,' and you feel honored to be part of all that.

My agent seems to think that my greatest stumbling block is always feeling as if I'm wrong for a part. I knew about the Marquis, from university days; he was a counterculture icon then. I've been in "Marat/Sade" and "The Marriage of Figaro"; if you look at anything to do with that period, the Marquis stands astride it like a Colossus. And I knew he was physically bloated and big, so I instantly read that into it. But when Phil got going, he started to talk about the artist as outsider, as maverick, and the Marquis as the beginning of a tradition that takes in Jean Genet and Henry Miller and Lenny Bruce. "The mind," he said, "I'm interested in the mind of the guy."

Then I heard that Kate Winslet was interested, and I am a really big fan of hers -- I'm fascinated by her repertoire. We mutually flattered and excited one another by saying, "Oh, I'll do it if she does it," or, "I'll do it if he does it." Which is sort of real in a way, because you think that with material like this, you need a great actress like her. Then, you're on a plane, you're going to do it, and finally you're standing around in a horsehair wig. Phil was the wild beat generation alchemist putting all this together. He was constantly grinning like a Cheshire cat over the whole production. He gave it this wonderful dangerous humor in the process of making it and in the substance of it.

I can play games with myself, and think: "This is Joaquin's movie, we are following the Abbé." But then Phil comes along and says I'm the ringmaster, not the figure on the side; I'm the one lighting fuses everywhere and leaving matches burning and not worrying where they fall. That gives you something. And so does Doug Wright's dialogue for the Marquis. It's not just written to convey information.

It's like when you read a Billy Wilder or Ben Hecht screenplay and you think, "This guy is so snappy and ironic and sharp and sentimental, all in the same little batch." The American wisecrack tradition powers the machinery of Doug Wright's script. It's got great zingers; I'm amazed at how florid Doug can get and still be as keen as a razor on a line. When the Abbé throws the Bible at the Marquis and says, "Learn from this," de Sade instantly picks it up, spits on it and says, "This God of yours strung up his only son like a side of veal. I shudder when I think what he'd do to me." You become aware that every time de Sade opens his mouth it's to say something lurid, provocative or foul, all to bait the other person into engaging with him. And as amusing and as provocative as that is, there's something desperate and painful about somebody that constantly has to keep seeking companionship in this way. We realized that was the undercurrent of the piece.

I mean, the guy is incarcerated. So like some old weird wasp living away in his little nest, he lures insects in so he can play. There's a great line in Doug's original play -- a great image of the Marquis that is not in the film. The Abbé refers to him carrying on "like a demented peacock." That became a really useful working image in terms of how I saw him strut and parade and be totally at home in his deluxe suite in the asylum, lounging around in a sort of shabby decadence.

Another great thing was the wig. I didn't want to have a wig that made me look like Captain Cook, because, burdened with that, I wouldn't be able to put across the vitality and immediacy of the material. But they found, through some etchings, a fantastic, louche, rather stylish and attractive headpiece and I realized that, with my physicality, he could look like some randy old mountain goat, with horns. Looking at the shape of that thing gave me another really useful image. It's as if de Sade is precariously standing on some craggy clifftop where you could topple at any moment. But he manages to perch -- elegantly. That's useful in terms of figuring out, how do you sit on a chaise longue? How do you breathe life into the incidental moments, for a guy who for most of the film is in one room?

Your wife, Jane Menelaus, is perfect in the role of de Sade's wife, and the one scene with the two of you is stunning. De Sade operates with her the way he operates with the audience, drawing her in with wryness, even tenderness, before turning on her.

It's the antithesis of great prison moments in movies; she brings over his dildoes.

Did the casting help that scene?

When I knew that Michael Caine was involved, and Joaquin was about to sign, I asked Phil, "Who's playing the wife?" And he said, "I don't know. I'm finding it really difficult to cast. People are looking or sounding too contemporary or they don't mesh with the quartet." I asked, "What are you looking for?" He said, "Somebody between 35 and 45, who has a vulnerability and a beauty and aristocratic bearing and also rich emotional undercurrents." Then he asked, "Your wife's an actress, isn't she?" I said, "Yeah, but she hasn't acted for a while. She's been parenting. But we worked together lots on stage." In a jocular sort of way he said, "Someone like her."

We got the script, and she read it, and I've never seen her get so fired up about a part. She has been very committed to our kids, but she said, "I'm going to go for this." I said, "OK, let's hire a studio." We put down a scene with me off camera. I encouraged her to just have a chat with the camera, because the people watching this wouldn't know her. We waited for a couple of nail-biting weeks, and then got word from casting. Phil might have hoped for some weird psychotherapeutic game-playing, but it was all on the page -- the scene cries out "domestic roller coaster."

You've talked about the choreographic elements of your acting. When you parade naked around Joaquin, you give the Marquis an odd tragicomic dignity.

It's part of his resilience, isn't it? At first you think that it's a great act of humiliation to strip somebody naked and then chain them up. But the Marquis manages to use that to probe to even deeper levels of provocation. I never went to dailies but the costume designer [Jacqueline West] went. At that point her job with me was truly over, but after seeing that scene she came back and told me, of my naked skin, "You're wearing it like another costume." The game got notched up to another level. That's how we played "Quills."

Shares