After just one viewing, I wouldn't want to leave the impression that "Monster's Ball is without fault. The final impression is that the movie has settled for a very appealing hope that "everything" between black people and white people can be all right one day. There are several implausibilities in the plot. I didn't feel that Heath Ledger was or could be Billy Bob Thornton's son -- younger brother, maybe. And maybe there are too many convenient deaths in a short span of time that set the Thornton and Halle Berry characters up to be the great black and white hopes of our time. But I'll forgive those things, and I'll admit that I never thought Berry could be this good or touching. Then I want to say that the picture has the best lovemaking scene in too long.

I need to fill in some story background -- but I won't give away the very suspenseful ending. Somewhere in the rural South (it doesn't quite feel like now), Billy Bob and his son are corrections officers at the state prison. (It is a family tradition: Billy Bob's invalid father, Peter Boyle, did the same job once.)

An execution is looming, that of a black man, visited by his wife and their obese son of about 12. It's another plot hole that Thornton never sees these visitors, or they him.

The black prisoner is electrocuted. Billy Bob is in charge of the execution, and Ledger throws up at the event. Billy Bob curses him out for such weakness. They fight. Billy Bob admits he hates his own son, and Ledger kills himself.

Shortly thereafter, Berry's son is killed in a hit-and-run accident, after which a rather helpless or trapped Billy Bob takes them to the hospital. We are meant to feel he has been changed by the two deaths, and so he and Berry are quietly drawn together.

Billy Bob is very good. It is asking a lot -- too much, even -- to have a thorough bigot and redneck turned into the spirit of kindness on a dime. But just as Thornton gave us real (and tedious) nullity in the Coen Brothers' "The Man Who Wasn't There," in this picture he is palpably present, sinking back into a kind of solitude, or grief, in which he might plausibly discover a better person. It's all too quick, but it's an honorable change for which the actor is working.

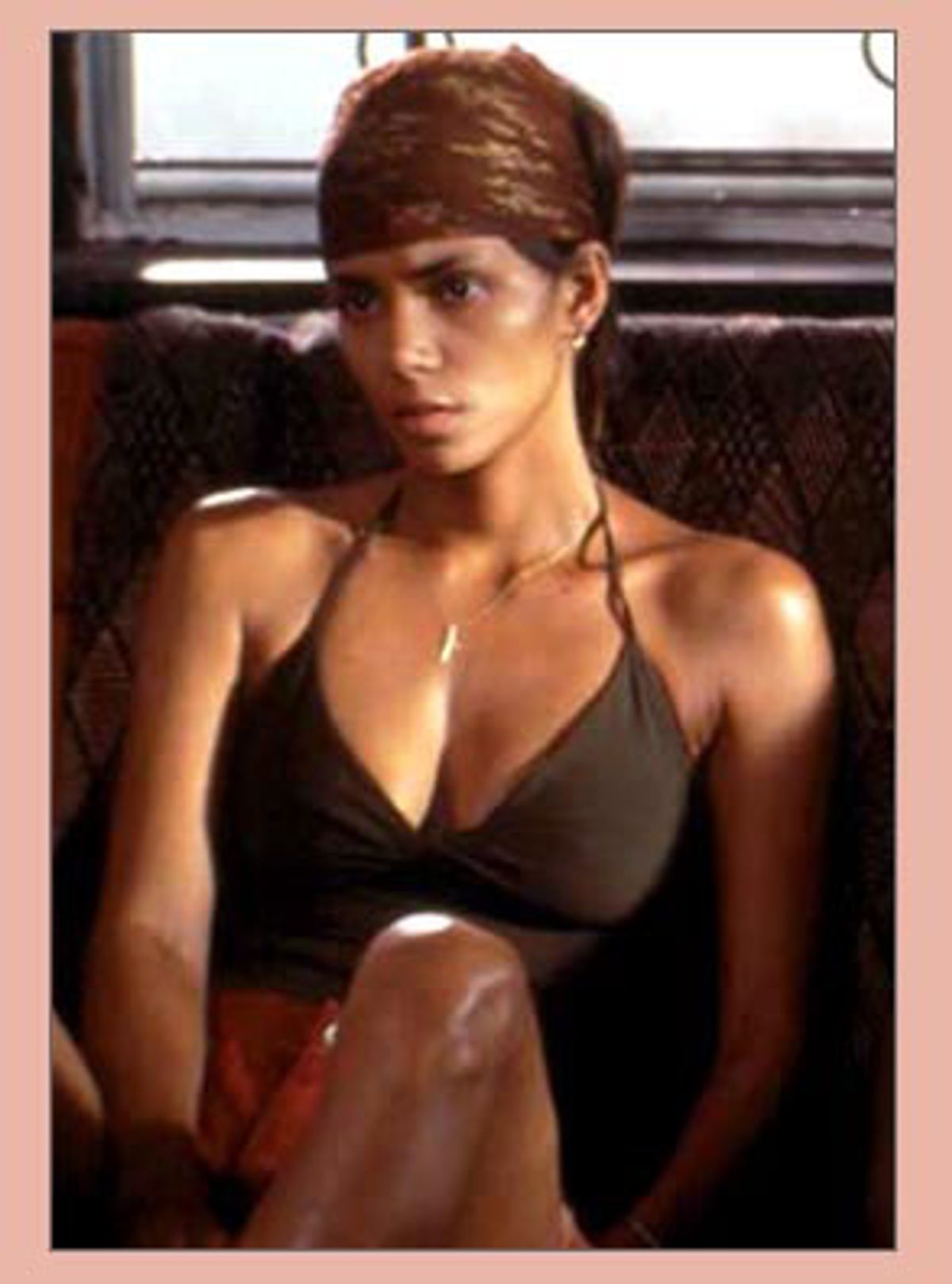

Then there's Halle Berry. Even with modest makeup and dark circles under her eyes, this is Halle Berry -- which is enough to stretch imagination that she passes as a nonentity in this southern backwater. We are looking at one of the more beautiful women on Earth: We know it -- and she knows it, no matter how diligent she is at being anonymous. Never mind, for in that effort she has found a way of moving (sluttish, bored, aimless) and a way of speaking (melancholy, uneducated, lazy) that makes a believable flake -- a pretty kid out of her depth. But an actress so assured that she can reach out and in one great needy embrace wrap up and consume the greater reticence or uncertainty in Thornton.

We know they're going to make love, and there's a way in which we know that once we see the half-naked Berry the real truth about her fruit is going to overwhelm the small-time narrative setup. But the ways in which Berry presents us with a wrecked creature, groaning, grunting, hissing, moaning for relief or abandon is not just heartbreaking and arousing. It's enough to make us forget that she looks like a goddess. The scene is very powerful (and it plays off the ways, earlier, that Thornton and Ledger have used the town's drab prostitute). Berry's character demands confrontation, full frontal embrace. She wants it all. And it is in her plunging down to some erotic base line that the film does really locate a bond between blacks and whites that gives cause for hope.

It takes a very strong scene indeed to absolve a confused movie from so many faults. Go see and hear for yourself.

Shares