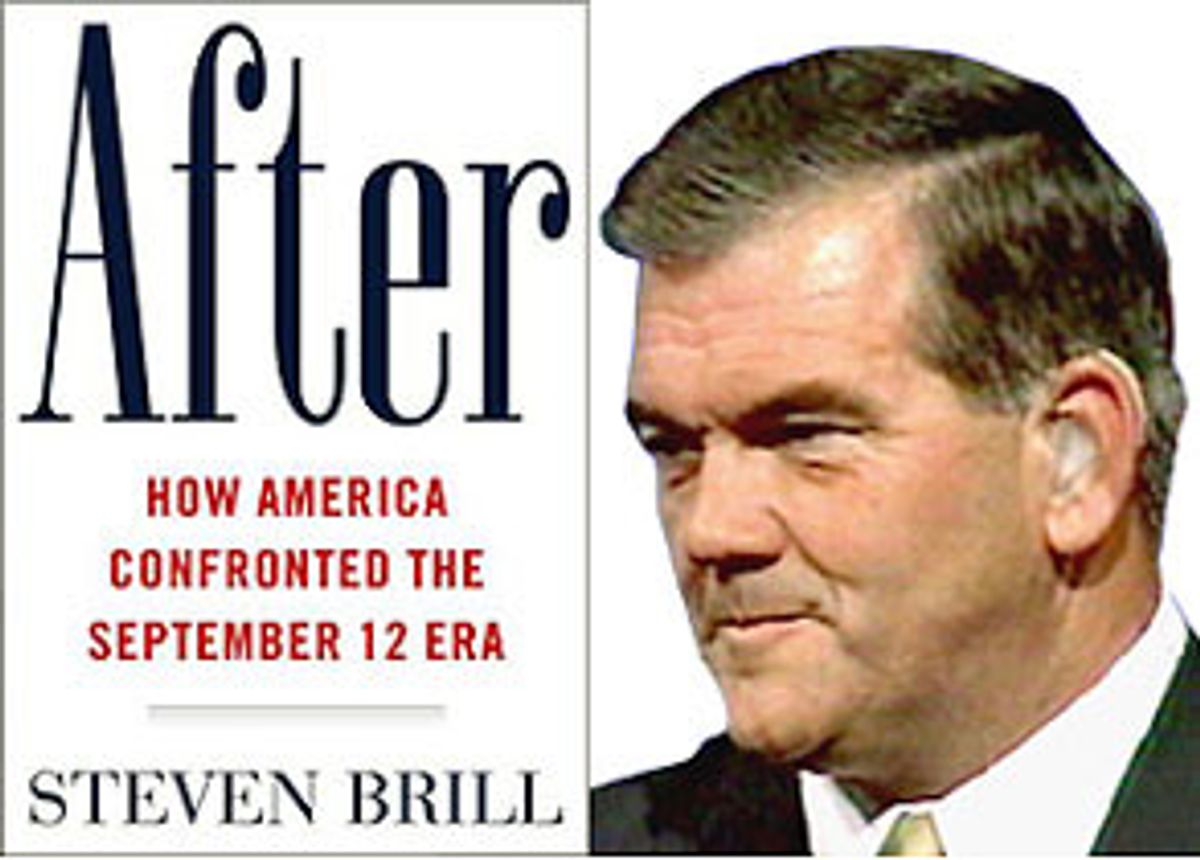

Editor's note: This week, Salon is publishing selected scenes from "After," Steven Brill's definitive, deeply revealing book about how America has changed since the national trauma of September 11. Brill, who started his career as an investigative reporter before becoming a media entrepreneur (the American Lawyer, Court TV, Brill's Content), draws from interviews with more than 300 people, as well as court filings, internal summaries of high-level government meetings and other documents to create his portrait of a nation struggling to redefine itself while holding on to its fundamental values. "After" is told through the eyes of a wide range of powerful and unsung people, from Attorney General John Ashcroft to ACLU executive director Anthony Romero, from a World Trade Center widow to the attorney for John Walker Lindh, from lobbyists in Washington to a Silicon Valley entrepreneur whose company makes machines that detect bombs in luggage. Chronicling their stories on a nearly day-by-day basis, "After," which will be published in April, is the most sweeping, yet detailed, account of what Brill calls "the September 12 era." It's a "towering achievement," in the words of New York magazine's Michael Wolff, in which "the granular becomes epic." Read Excerpt 1.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Steven Brill

April 1, 2003 | Wednesday, September 19, 2001

Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge was in the governor's mansion at about 1:30 on Wednesday when his secretary said that Andrew Card, the White House chief of staff, was calling. Ridge immediately took the call.

Card wanted to know if maybe Ridge could come down to Washington from Harrisburg to talk about a new job they were thinking about involving homeland security. It turned out that Ridge was already supposed to be in Washington the next day to testify at the International Trade Commission in support of his state's steel industry. Stopping by for a chat would be no problem, he told Card.

Ridge aides recall that he seemed preoccupied after the call, but that he kept mum. About an hour later, the staff became more curious when the secretary put through a second call from Card. After they chatted for a few minutes, Card said, "someone else wants to talk to you," and Vice President Cheney got on the phone.

Cheney told Ridge he was delighted that he was coming to talk about the job, that it was a job that Cheney and his staff had been focusing on in the last few days, and that he was hoping Ridge was prepared to give it serious consideration. Ridge was surprised that things had gotten far enough that the vice president was already involved.

At about 4:15 Ridge left in the state plane for a funeral in Meadville, Pennsylvania. When the plane returned to Harrisburg at about 8:30, Ridge was greeted by an aide as the door opened. The president had been trying to reach him.

Ridge went quickly to the governor's mansion where he could take the call from the privacy of his bedroom. The president was also glad Ridge was coming to town so quickly, he said, because this was a really important job.

As he finished the call, Ridge's wife, Michele, came in, surprised to see him at home. "I took one look at his face," Michele Ridge recalls, "and stopped. I knew something was going on."

"We have to talk," Ridge said. "Right now."

"Is it your mother?" Michele asked. Ridge's 78-year-old mother had recently been in the hospital for surgery.

"No," he replied. "Let's talk."

"I'm an army brat," says Michele Ridge, "and was used to getting told we were moving. And Tom was drafted, too. So for some reason, without him saying it, this seemed to me like the time he'd been drafted -- which it kind of was."

As Ridge's aides speculated about all the calls, Michele told him she knew he had to take the job. But they also discussed another problem: With Ridge needing to rent an apartment in Washington and the family needing to find a home in Harrisburg at least until the end of the school year, Michele was going to have to go back to work. There was no way they could suddenly assume all those new housing costs, plus keep the kids in private school, on his White House salary (which he later found out was $140,000). Plus, she'd have to buy a car (they had not needed one of their own in the seven years he had been governor), and figure out how to pack up their files and furniture with none of the usual transition costs budgeted by the state for this kind of sudden move.

The Ridges decided that they could not tell anyone, including their children -- son, Tommy, 14, and daughter, Lesley, 15 -- until the next evening, because, as Michele remembers, "the kids are so networked on the computer that they were bound to let the word out."

At 6:45 the next morning, Thursday, September 20, Ridge flew to Washington for his testimony. By 9:30 he was in Card's office at the White House. Soon Cheney joined them, then the president. The meeting had all the urgency of a wartime conference. They outlined the coordinator's role. Bush promised his friend that he'd have his full backing to shake things up. But they needed an answer now because the president wanted to make the announcement of a new homeland security chief in his address to Congress scheduled for that evening. Ridge shook the president's hand and said yes.

Tom and Michele Ridge talked to Tommy and Lesley on Thursday afternoon, just before Ridge left for Washington to be there for the president's announcement. It helped that the kids knew and liked the Bushes. They'd spent weekends with them in Kennebunkport, Maine (at the Bush family compound), when their father and Bush had been fellow governors. And this past summer they'd stayed at the White House during a July 4th celebration. Bush had also stayed with them a few times at the Pennsylvania governor's mansion. But this was quite a shock. Would he really leave Harrisburg and the governorship? What would this job be? What about the kids' schools?

Ridge said that Washington was only about a two-hour drive and that he'd commute on weekends, at least until the school year ended. Then they'd see how things were going.

Ridge would later say that the decision was not that hard, and was made easier by his longtime friendship with Bush. "The president wasn't asking me to run into a burning 110-story building like those firemen did," is the way he put it. "This sacrifice, if it was one, was the least I could do."

Nonetheless, it was an extraordinary decision, and one that was emblematic of the time -- that brief, probably too brief, period of weeks following Sept. 11 when for most Americans the unprecedented urgency of the moment was such that no sacrifice, no disruption of normal life, seemed too much. In the space of about 21 hours, the seven-year governor of Pennsylvania had quit his job. He had forced his family to find a new home. (Ridge's successor, Lieutenant Governor Mark Schweiker, soon decided to let the Ridges stay in the mansion until December 31.) He had left his family. His wife would have to go from being a first lady with a staff of five involved in a variety of community service projects to a working mom. And he had gone from being a chief executive to a staff position that was, at best, ill defined, and would soon be challenged and belittled.

October 12, 2001

On the same morning that the USA Patriot Act was being pushed through the House by a lopsided vote after having been supported 96-1 in the Senate, and on the day after the Senate passed the aviation security bill 100-0, the executive committee of the national board of the ACLU convened in Washington -- where one of the first issues up for debate was whether the ACLU should continue to oppose metal detectors at airports. Since 1973, the official ACLU policy had been that the organization was against the screening of airline passengers for guns and other weapons because it violated Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches.

Amazingly, the ACLU position had never changed, despite attempts over the years by some members of the board to get it amended. Now, the organization's executive director, Anthony Romero, was determined to get the policy expunged before he started reading about it in the press.

After about an hour of discussion, the executive committee voted unanimously to repeal it. But when the full 84-person national board, which includes representatives from the 50 states, would meet two days later, things didn't move that quickly. After a debate that lasted much of the morning, the repeal resolution passed by a voice vote, but not at all unanimously.

Among those who wanted to keep the ACLU on record against screening all passengers for guns and knives was Arthur Heyderman, the delegate from Iowa. "We should not cave in to the pressure of the moment," he argued. "The government should do a better job of figuring out who has to go through a metal detector. They should have probable cause before making someone go through it."

How are they supposed to check every passenger for probable cause, one of the other board members asked. "That's their job, not ours," Heyderman replied. "We have to stop worrying about how they do their jobs. Why can't they just put an air marshal on every plane," he added. "Then they wouldn't have to worry about searching people or finding probable cause. If that's the price we have to pay not to violate our right not to be searched, we should pay it."

Heyderman, who also argued that we should not be bombing Afghanistan "any more than we should have bombed Chicago because Al Capone lived there," is part of what Romero calls "an old-guard faction at the ACLU, which has a lot of respect in the organization but which does not always prevail." Yes, they make his job more difficult in the September 12 era, he says, but they also "help us keep to our principles."

Beyond the metal detector issue (which Romero did succeed in disposing of without any publicity), the ACLU's three-day policy meeting featured what Heyderman would later call "debates over efforts we have to make to reach out to people to get them to slow down. Ashcroft wanted to scare people to death, and we had to figure out how to stop that."

Shares