In 1972 I found myself in the children's summer reading program at the local public library. My mother thought the program would amuse me -- an advanced reader by the age of 8 -- while she taught summer school. She couldn't have been more wrong. I was so bored. I wanted to read material from the adult book stacks, but I wasn't allowed to wander them unaccompanied by a grownup. So, stuck in the kiddie room, I decided to read every children's book in the library in alphabetical order.

What I didn't realize was that I was also on a mission. Books were certainly an escape for me that summer -- an escape from boredom, an escape from my mother's nagging about being more sociable, an escape from the smoggy heat of Los Angeles. But I was looking for more than a window on the world to distract me from my resentments and worries. I was also looking for a mirror to affirm my experiences as a bright middle-class black child living in a white suburb.

I couldn't have articulated my need in those terms at the time, but I could tell that my experience didn't fit the norm. So I became a misanthropic bookworm. I hated parties so much that I'd bring a book with me just in case I found a chance to slip off to a quiet corner to read in peace.

I confess: I was a hyper-articulate terror. I'd correct people's pronunciation, scolding black kids to say "ask" instead of "ax" and reminding white kids to say "anything" not "anythin'". A few black friends stuck with me into my teens but constantly admonished me not to be such a geek. When I confessed to one friend that I wanted to visit New York City because Dorothy Parker, my idol at the time, had lived there, my friend just rolled her eyes and replied, "God, you are too weird for words."

During that summer in the library I read a lot of books about young African-Americans. But I couldn't identify with them. Either the books focused on memories of growing up poor in the segregated South, like William L. Armstrong's "Sounder," or they closely followed the formula established by Ronald Fair's "Hog Butcher" and Kristin Hunter Lattany's "Soul Brothers and Sister Lou": inspiring portraits of inner-city youth struggling to escape a poverty-stricken ghetto via unique talents.

None of those stories spoke to me in the same way as Kin Platt's sad tale about a little white boy's nervous breakdown in "The Boy Who Could Make Himself Disappear." I'd read the painful story over and over again as if picking at a scab. It reminded me of life with my own high-strung mother.

I also loved Sally Watson's historical novels (which have been newly reissued by Image Cascade Publishing due to the networking of long-time Watson fans who met over the Internet) about girls who defy the conventions of their day. When I was a kid, I repeatedly checked out Watson's "Mistress Malapert," a tale about an aristocratic Englishwoman who masquerades as a boy in order to join William Shakespeare's theatrical troupe. Recently, I discovered a new Watson favorite, "Jade," in which a young girl becomes a pirate after aiding a slave rebellion aboard a ship bound for colonial Virginia.

I figured that if I was such a misfit, I wanted to be a spectacular misfit like Watson's heroines. I kept reading and kept searching for a model that reflected me, a dark girl in the bright suburbs of L.A.

I finally found what I was searching for when I pulled "Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and me, Elizabeth," by E.L. Konigsburg off the shelf. I immersed myself in the tale of how a fifth-grade witch named Jennifer drafts the lonely new girl at school to be her apprentice so that the two can concoct a flying ointment. I loved Konigsburg's story about interracial friendship and witchcraft not so much because the title character, Jennifer, was a black girl isolated at a white suburban school, as because she was so inventively odd. I could relate to a girl who was such a voracious reader that she could walk down hallways while reading without looking up.

A year and a half later I better understood Jennifer's plight when I became the first black child to ever attend our neighborhood elementary school. My parents and I didn't discover this fact until I showed up for class on the first day. It was 1974 and we, naively, never noticed that we were one of the first black families to reside in that part of town.

A little freaked out by the weightiness of the situation that first year, I often hid out in the library, rereading favorites like "Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and me, Elizabeth." I found solace in Jennifer's quirkiness as I fought loneliness and isolation. Konigsburg's tale helped me to process, on an unconscious level, how vulnerable I felt being the sole black kid at school. It was the first time that I had felt on display, and I could never completely shake the feeling that I was a target, despite the general friendliness of most of my classmates. Indeed, their fumbling politeness made me feel like a living civics project. Their excitement about taking part in that brave social experiment called integration made me feel shy and resentful.

Jennifer taught me that self-invention is one of the best ways to protect yourself from rejection; how can you be rejected if the person who fails to win favor is not really you anyway?

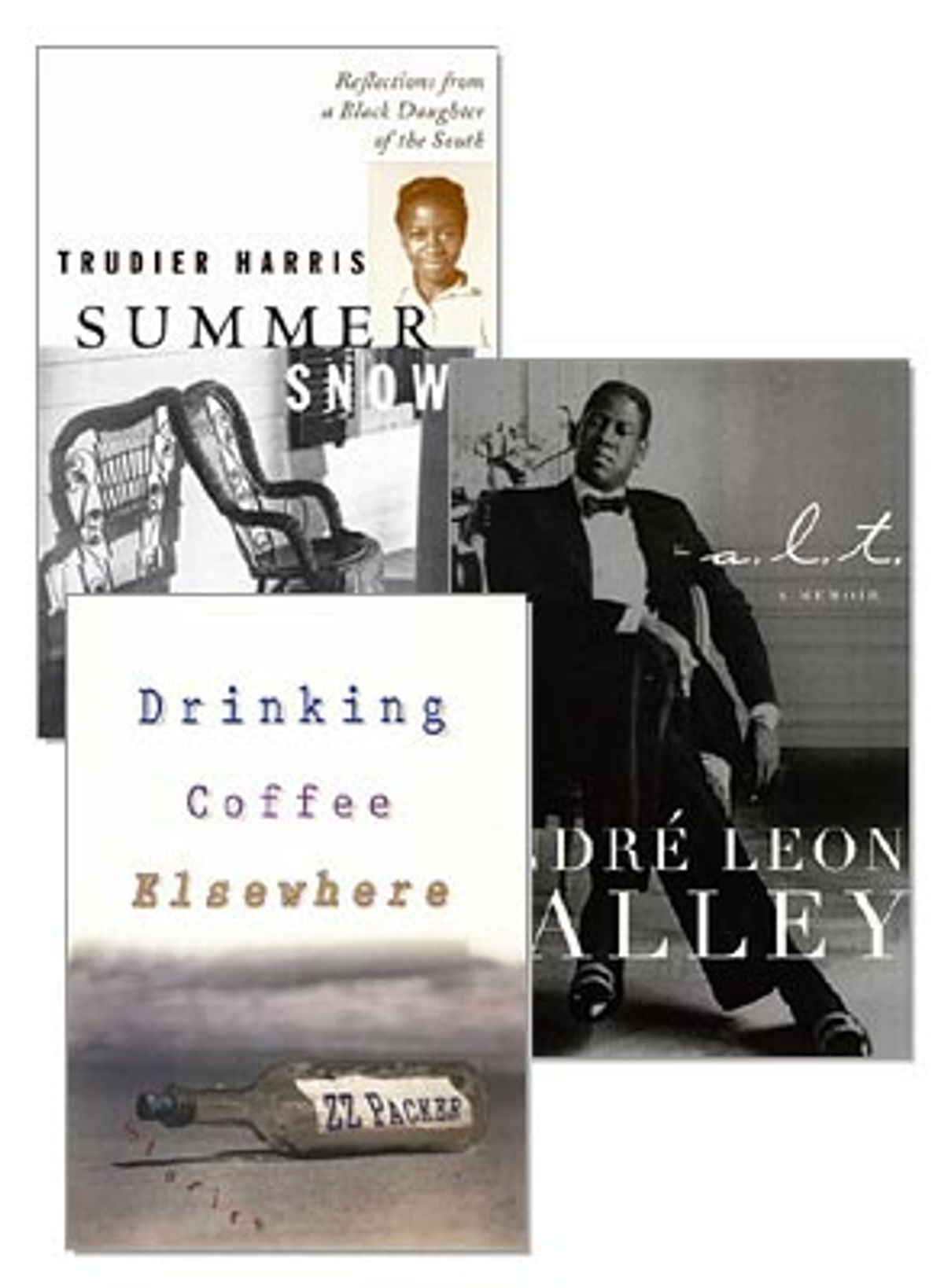

I've spent years looking, without much success, for books that made me feel the way I did reading "Jennifer, Hecate." But I've finally found three books that accurately portray the black geek experience: ZZ Packer's "Drinking Coffee Elsewhere," Trudier Harris' "Summer Snow: Reflections From a Black Daughter of the South" and André Leon Talley's memoir, "A.L.T." Each book gives readers insight into African-Americans, like the fictional Jennifer, who live at a distance from the mainstream black community due to sexual orientation, geography, sensibility, education or simple perversity.

At first glance, one would never suspect that these three writers had anything in common other than their African-American heritage. Packer's an extremely talented fiction writer whose first collection of short stories was chosen by John Updike as NBC's "Today Show" Book Club selection for May. Harris' collected essays are about her efforts to earn a Ph.D. in English. Talley, an influential journalist who writes for Vogue and Women's Wear Daily, is a very tall man who regularly turns up at fashion shows looking like the love child of Wilt Chamberlin and Little Richard in bespoke suits paired with floor length mink coats.

Yet all three authors draw on a Southern upbringing to reveal the rich inner lives of outcasts who use humor to keep loneliness from sabotaging their ambitions. Continuing the legacy of James Baldwin, Packer's stories focus on smart young people growing up as fundamentalist Christians. Packer's characters struggle to keep the hegemony of church, tradition and family from smothering a budding sense of autonomy, while Harris and Tally look back on their Southern roots with more affection. The first third of Talley's memoir, for example, is devoted to his upbringing in North Carolina. A child of divorce, he was raised by his churchgoing grandmother, Bennie Frances Davis. Her sense of style and sensitivity to life's pleasures shaped Talley's character as much as his mentor, Diana Vreeland, did.

But the bonds of family and tradition are not enough to protect these writers from being outcasts. Occasionally the books touch upon casual American racism, but the point of their tales is less about the hostility encountered in the larger world than the rejection they receive at the hands of their fellow African-Americans. All three writers explore the idea of the Other's Other, revealing intra-black conflict and prejudices. Harris finds that her education impedes her marriage prospects and complicates community ties. She notes with pain how neighbors and church members shy away from her, intimidated by her elevated status as a professional woman:

"Receipt of the Ph.D. is the ultimate admission to nerd-dom. It is also the beginning of a lifetime of 'set aside' experiences. Countless black folks who have been introduced to me over the years have immediately resorted to calling me 'Doc.' From their perspective, 'Doc' is a general title of respect, but I would maintain that it is ritual without substance, a game people play to remind you constantly of how different you are. 'Doc' works as many of the interactions with black nerds work: It claims and rejects at the same time. It admits that you are well educated, but it also sets you up -- constantly -- as a noticeably different person precisely because you are well educated. You become the streetlight at the entrance to the community. It's obvious that you're there, and you may be something that no one else in the community is, but who the heck wants to be like you?"

Talley and Harris both write in moving detail about the pain of being misunderstood, or even rejected, for their ambition. In the segregated South, they expected whites to underestimate their abilities but find it difficult to be rejected by the black community for aspiring to nontraditional professions. In her essay "Mind Work: How a Ph.D. Affects Black Women," Harris discusses how some African-Americans often see education as primarily a key to financial upward mobility and fear that too much education can cause harm for their offspring: "There was a general belief, however, that too much education created problems. Those problems might be manifested at the simple level of a cousin who didn't have any mother wit. Or, more dangerously, they might be manifested in insanity."

André Talley shares his own experience with closed-mindedness. He recalls a cousin asking him what he wanted to be when he grew up: "I had thought a lot about my potential future career as I pored over my collection of magazines, so I decided to go ahead and tell him. 'Well, okay. I'm going to be a fashion editor at a magazine!' His mute response was a dazed and disgusted look, in which he furrowed his brow until it was as wrinkly as an old man's, shrugged his shoulders and walked out of the room. His rudeness stung me, though, as you know, if it had any effect on what I eventually chose to do with my life, it was to spur me on. Still, I felt as if he'd betrayed me by asking for a confidence and then shrugging it off. I thought about his reaction as I sat on the edge of the bed and looked out the window, and I realized that his opinion didn't matter much to me, not in my heart. But after that incident in my bedroom, I decided to keep my dreams more firmly to myself, and I never discussed them again with any but my female friends until college. (You can analyze this, if you will, but I think such responses are common among people who don't live according to the expectations of others.)"

Characters in Packer's stories face these same obstacles in the '80s and '90s. A black nerd must use his debate team prize money to bail his alcoholic father out of jail. A recent college graduate's neighbors in Baltimore cannot understand the young woman's plan to live in Japan and teach English.

But Packer is strongest when she writes about how group dynamics influence an individual's behavior. She wisely starts the collection with one of her funniest tales, "Brownies," which reads like an O. Henry story dictated by Amiri Baraka. A fourth-grader narrates how a camping trip taken by her African-American Brownie troop subverts racial assumptions. After a confrontation with a white Brownie troop sharing the same campground, the narrator witnesses two black girls in her troop manipulate the other girls for their own amusement. The two bullies receive a surprising comeuppance, not only proving that even the meekest geek can prevail, but also that pain and humiliation serves as a strong bond among outcasts, whatever their background.

Packer creates such vivid characters that I can't help but worry for their future as I once wondered about Konigsburg's Jennifer. I hope that they will survive their painful youth with their ambitions intact, as Harris and Talley have done. Talley eventually found people who understood him and encouraged his dreams once he obtained a scholarship to Brown's Ph.D. program in French studies. He eventually abandoned his studies to embark on a career as a fashion journalist in New York City, where he befriended icons like Andy Warhol, Halston, and Karl Lagerfeld. Harris stayed the course and obtained her Ph.D. in English. She is a professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

I hope that younger bookworms discover these books this summer; I feel so much better knowing that these authors' experiences and perceptions paralleled mine, and they have shown me that some of my oddities were actually coping mechanisms. ZZ Packer has taught me that having a sharp tongue and a twisted sensibility is a form of self-protection. Trudier Harris' wise observations validate my experiences as a black intellectual, while André Talley reminds me that I can accomplish anything if I'm lucky enough to have someone's unconditional love and a strong faith.

Shares