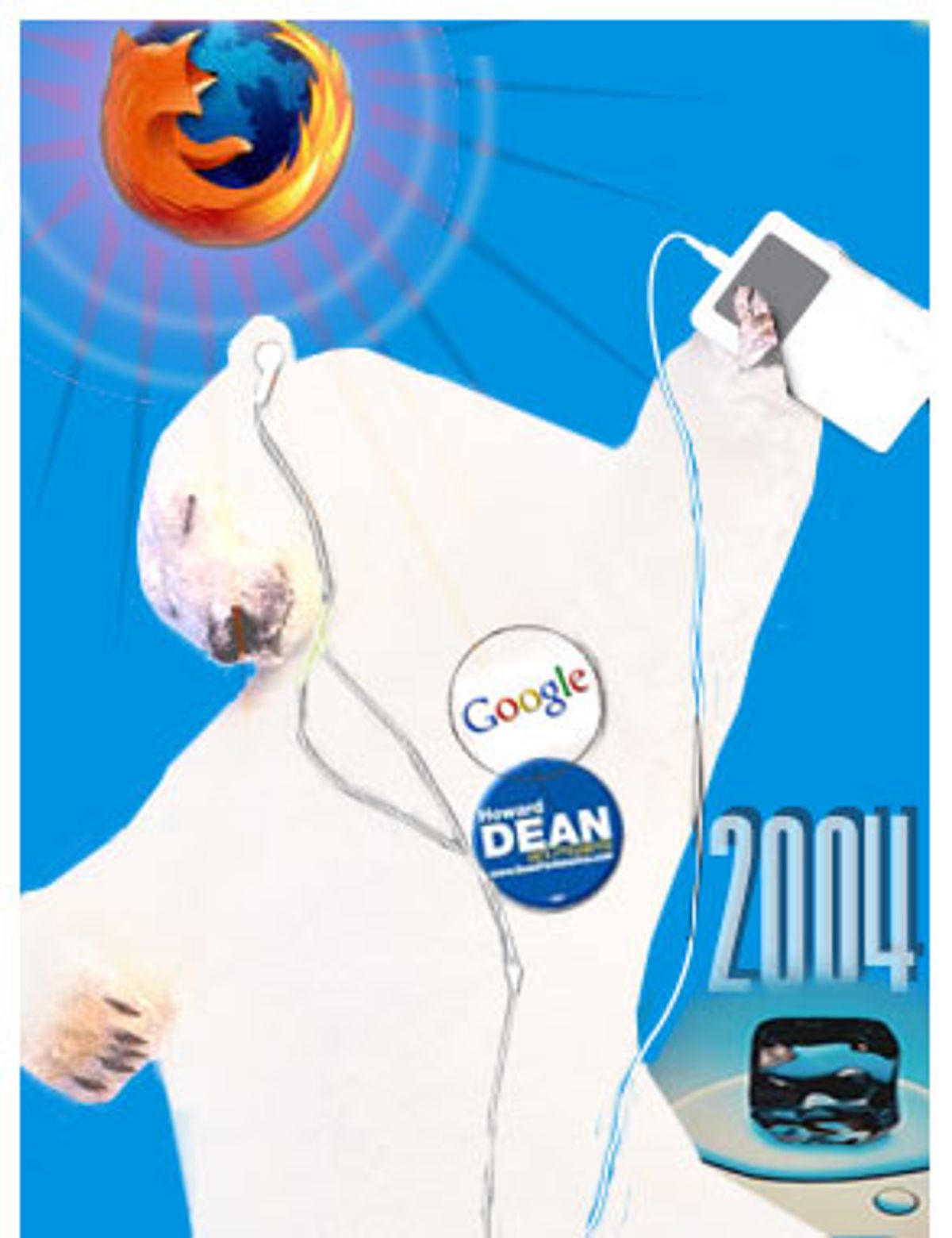

The blogging of the president

It seems strange to contemplate now, but around this time last year just about everyone in the political establishment believed that Howard Dean would handily win the Democratic presidential nomination in 2004, thanks mainly to his deft use of what experts were calling a powerful new political tool -- blogs. That, of course, didn't happen; though Dean used his formidable online operation to raise more money and to put together a more robust organization than any other candidate, his blog savvy mattered little in Iowa, New Hampshire and other primary contests.

In retrospect, Dean's loss should probably have been a sign to proponents of Web-based political activism that they needed to spend some time thinking of creative ways to convert a vibrant online movement into an effective offline tool. But in the heat of the campaign there was no time for such introspection, and instead bloggers -- the most powerful of whom seemed to be liberals, epitomized by the denizens of Daily Kos -- raced forward with their crusades.

And for a while, things looked peachy. With the advent of blog-based ads, money poured in to political campaigns (not to mention to the bloggers themselves). Bloggers also managed to affect the political news cycle (remember "Rathergate"?) and they got themselves invited to both parties' conventions. But it was hard not to think of the Democratic defeat of Nov. 2 as a Dean-in-Iowa redux for the bloggers. John Kerry raised a lot of money online, but he didn't win. And neither did many of the congressional candidates who'd financed their campaigns with blog money. Readers of Daily Kos funneled half a million dollars to a "Kos dozen" of congressional candidates, and every single one of those lost at the polls.

So what happened? Was the entire online political effort something of an illusion -- a mere echo chamber of blue-state optimism, all sound and fury, signifying nothing? Alas, it sure seems that way now. But here's hoping that by 2006, smart bloggers find ways to break through the echo chamber, and people-powered online movements begin to matter in the real world.

-- Farhad Manjoo

The unwired Net

Sitting at a departure gate at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, I received an e-mail from the Orbitz travel agency informing me that the flight I was waiting for had been delayed -- before any such announcement had been made over the public address system. It was a wireless moment, one of many this past year.

In the same airport, there was the anxious man who walked up to where a woman and I were seated hunched over our laptops, and asked, "Are you getting Wi-Fi here?" in a voice that was equal parts hope and desperation. Or there was the time in New York City over Thanksgiving, when I turned on my laptop and discovered that were seven wireless networks in range of my father's house. Or just simply, the happy day when I brought my new wireless-enabled laptop home and realized that I was no longer chained to my network, that the Internet was where I wanted it to be, when I wanted it to be.

In 2004, the wireless Internet hit critical mass. Long a marker of the particularly fevered geek (remember him trying to adjust his little antenna to pick up that feeble Metricom signal?) the ability to log on, from anywhere, at any time, without encumbrance, is now rightly seen by the computer-using masses as a basic human entitlement.

Advances in technology often, rightly or wrongly, are seen to subtract as much from the quality of human life as they add. E-mail eviscerates the handwritten letter; computers isolate humans from real-world interactions; cellphones intrude upon public space. But wireless Internet connectivity is hard to fit into that zero-sum model. It really does free one from constraints, and it's hard to think of the downside. It embodies an implicit promise in the whole digital revolution -- that all this is happening to make our lives richer and better, that the Internet is here to serve us, not to overload and oppress us. Technology should not be hard, and finding out what you need to know should not be a chore. Things should just work. The Internet should just be there.

Information doesn't necessarily want to be free, but we definitely all want it to be easy. In 2004, thanks to wireless, the Internet became easy.

-- Andrew Leonard

It's getting hot out there

The Kyoto Protocol is finally a global reality, but the world's biggest greenhouse-gas emitter, the United States, is nowhere to be found.

Among the loads of depressing global-warming news this year: A four-year scientific study commissioned by eight nations with Arctic territory, including the United States, found that polar bears will be some of the first victims of the world's failure to curb greenhouse-gas emissions.

But not even the apocalyptic hurricanes in Florida could turn global warming into a real issue in the November election. California tried to do something about it -- setting its own carbon dioxide pollution standards for cars -- but promptly got sued by automakers. Carbon sequestration and other technological fixes that could help mitigate the impacts of the world's voraciously growing need for cheap energy showed promise. But there was little evidence that they'll be widely implemented in the U.S. in the near term, since it's simply cheaper not to.

The news about global warming -- and the United States' failure to do anything about it -- became so feverish this year that even the queen of England felt obligated to descend from her throne and sound the alarm. She wasn't the only one. After the reelection of George W. Bush all but ensured the continuation of the United States' do-nothing policies on the issue, former President Clinton told his fellow Democrats to quit whining in defeat and create some viable legislation around the issue.

God save the queen, Clinton and the world from global warming.

-- Katharine Mieszkowski

Was the election hacked?

A couple months after Nov. 2, there's still no definitive proof that George W. Bush or any other candidate came to office this year thanks to electronic voting fraud. But to judge from the online din -- every second e-mail purporting to prove that something's fishy with the results -- a significant minority of Americans refuses to believe that this election was legitimate. This isn't surprising -- it's exactly what experts predicted would occur as a consequence of the wide-scale adoption of paperless electronic machines at the polls. Because these systems record, store and count their ballots digitally, they offer elections officials no way to prove that an election's results reflect the will of the voters, rather than the work of a hacker. As a result, political losers -- this year, supporters of John Kerry -- understandably have a hard time believing that an election conducted electronically has been essentially fair.

Since Salon first began reporting on the shortcomings of electronic voting machines (on Election Day 2002), the issue has leapt to the fore of the public consciousness. During the past year, many mainstream news organizations (led by the New York Times' excellent editorial page coverage) devoted significant space to the issue, and some forward-thinking elections officials (notably in Nevada and California) acted to reform the system by requiring paper trails in their voting machines.

Now that the election is over, Americans -- especially those who have no confidence in this year's results -- ought to push authorities in other jurisdictions to adopt similar measures. And Democrats are not the only ones who have an interest in this: The legitimacy of all elected officials in America is at stake. When a candidate who wins by 3 million votes is still seen by many Americans as possibly fraudulent, reforming the election system would seem to be an urgent matter for Republicans as well as Democrats.

-- Farhad Manjoo

Image nation

The year in pictures online was bloody and revolting, full of images depicting the most grisly, graphic violence. And then, there was Paris Hilton. The question of the year wasn't, should these be published? It was, can you bear to look at them? And what did it mean to watch the last seconds of a man's life before his execution, filmed by his captors for worldwide distribution? Or an heiress, famous for being famous, copulate?

Horrifying torture pictures from the Abu Ghraib prison were trumped only by the gruesome beheading videos coming out of Iraq.

At Abu Ghraib, cameras and videos were used both as sophisticated implements of torture, and later as the tool that exposed those abuses. When U.S. soldiers brutalized and degraded Iraqi prisoners, they took pictures to further humiliate the captives, threatening to ruin the prisoners' reputations by showing the images to families, neighbors and friends. But those same images exposed the abuses in the media and online.

Photos and images created by both soldiers and insurgents helped shaped the debate about Iraq, but could you always trust what you saw?

Photo blogging became as easy as uploading pictures to one of the rapidly multiplying photo services, from Ofoto to Smugmug to Flickr. And it turned soldiers -- and everyone else -- into citizen reporters.

Documenting the daily vagaries of our own lives on camera phones and digital cameras and uploading them to the Web became as ordinary as blogging, e-mailing or instant messaging.

We're all embeds now.

-- Katharine Mieszkowski

The war against sharing

The year seemed to begin well for the music industry's fight against peer-to-peer file traders. Record sales were up slightly, and many in the industry attributed the rise to the industry's extremely punitive copyright-infringement lawsuits against individual file traders. More than that, though, executives were buoyed by the visage of a white knight on the horizon -- a savior in the form of Steve Jobs, the CEO of Apple, whose stylish iPod and brilliant iTunes Music Store looked to spark a revolution in the way we experience music.

Now things look somewhat less rosy for the music industry, not to mention for Hollywood and other content owners. According to experts, industry lawsuits prompted no appreciable drop in online file-trading activity, although there does seem to have been a shift in the P2P trade: Instead of downloading singles, traders are increasingly interested in downloading much bigger chunks of content, such as full albums, television shows, and entire movies. BitTorrent, the peer-to-peer application celebrated by techies for its capacity to move extremely large files, became both very popular and easy to use in 2004 (especially when combined with RSS, the Web syndication service that ought to get 2004's award for Web geeks' most beloved New Thing) -- a development that doesn't sit well with the media firms.

But while the illegal trade flourished, the legal market for digital music also hit new heights. Apple's iTunes store has sold more than 200 million songs, and its success has prompted many rivals -- including RealNetworks and, more interestingly, Microsoft -- to launch their own online music shops. The iPod, meanwhile, became a kind of cultural icon in 2004, landing on the cover of Newsweek (headline: "iPod Nation") and swelling Apple's bottom line.

But the music industry seems eager to squander even the goodwill of all these shiny happy iPod people. Still more willing to fight its battles on Capitol Hill rather than the marketplace, record labels got their friends in Congress to introduce draconian anti-infringement legislation this summer that would mete out severe penalties to anyone who "intentionally aids, abets, induces or procures" copyright violation by a third person. The measure -- known as the Induce Act -- is so restrictive, critics say, that under its terms many of the technologies we hold dear would never have come to pass. According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation: "If this bill had been law in 1984, there would be no VCR. If this bill had been law in 1995, there would be no CD burners. If this bill had been law in 2000, there would be no iPod."

-- Farhad Manjoo

An open-source slam dunk

In the summer of 1999, Salon was invited to observe a showdown at PC Week's testing labs in Foster City, Calif., between Microsoft Windows and Linux. The atmosphere was tense. The Linux representatives were young and arrogant; Microsoft's were middle-aged and arrogant. But at perhaps no moment did the Microsoft reps' self-satisfaction shine through more irritatingly than when they noted the superiority of their in-house approach to software development as compared to the collaborative, distributed, open-source way of doing business. Look at the browser market, one marketing manager noted. A year before, Netscape had released the code to its browser and started the Mozilla project. But it was going nowhere, and in the meantime Internet Explorer 5.0 was taking over.

To open-source advocates, the comment was cutting. Netscape had generated oodles of media hype when it released the source code to its browser, but there was no denying Microsoft's ensuing total domination of the market.

At Salon, we've covered the saga of Mozilla closely ever since, and we've marked several points at which we thought the Mozilla browser had made significant progress. But it often seemed we were shouting at deaf ears. Internet Explorer continued to reign supreme, and when we told our friends and relatives that there was an alternative, they looked at us kind of funny -- like: all that free software stuff was cute back in 1999, but now you're beginning to sound like one of those freaks who still think the Amiga computer is set for a big comeback.

Then came 2004, the release of the 1.0 version of Firefox, the stand-alone Mozilla browser, and the consequent first decline in Microsoft's browser market share in years.

Back in 1999, everything happened on Internet time. But writing good code isn't easy to speed up. Firefox is welcome proof that open-source software programs can be user friendly, easy to install, and competitive with Microsoft. If Salon awarded a Program of the Year medal, it would go to Firefox.

-- Andrew Leonard

The incredible disappearing job market

Software developers, designers and customer-service workers have been forced to face the reality that the job market is becoming as international as the market for the products they buy, make and support. Outsourcing has brought the downside of globalization to the American middle class.

But for every underemployed U.S. software developer, how many people in other countries now have hope of finding rewarding and lucrative work? And for every American worker who lost a job to outsourcing, how many others saw their company stay in business and find new markets because of it?

The irony is that some of those offshore outsourcing shops have come to embody the so-called American dream better than some U.S. companies, like Electronic Arts, whose employees routinely work seven-day, 80-hour weeks. And the customer-service call that connects you to the other side of the world became so common that American support workers with Indian names had to get used to callers assuming they were actually on the subcontinent.

Still, in the United States the debate rages on: how best to cushion the blow when American workers lose their jobs to workers overseas.

-- Katharine Mieszkowski

Can California cure George Bush?

George W. Bush began his presidency by forging what he portrayed as a grand compromise on the federal policy surrounding embryonic stem cells, the "undifferentiated" cells that researchers believe could lead to treatments for such ailments as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes and perhaps dozens of other diseases. On Aug. 9, 2001, Bush declared that he would allow the government to fund research on stem cells that had already been created by that date, but he would prohibit federal money from going toward the creation of any new embryonic stem cells (which requires the destruction of embryos that some believe represent "inviolable" human life).

In 2004, the shortcomings of Bush's compromise became apparent to all. Only 23 stem cell lines now qualify for federal funding, a pool that scientists say is woefully inadequate for the research that needs to be done. Consequently, many leading universities moved to fund large stem cell labs with private money -- Harvard led the way with its creation of a $100 million effort. The biggest news, though, came in California, where voters approved a $3 billion bond measure to fund research on embryonic stem cells.

California's effort seems likely to prompt other states to open their vaults for stem cell research -- New Jersey and Wisconsin may be the first to follow. But as conservatives enjoy renewed power in Washington, there is a very real worry that some will try to push for a complete ban on such research.

-- Farhad Manjoo

Hydrotopia?

If you thought that in a few years you were going to be driving around in a hydrogen fuel-cell car that emitted nothing but water vapor from the tailpipe, you got a smoggy reality check this year.

California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger lent his considerable political clout -- and star power -- to the hydrogen hype, announcing that a network of fueling stations would be ready for action in the state by 2010.

But critics argue that hydrogen technology and infrastructure are decades from being ready for the mainstream, even as maintaining an adequate supply of oil gets ever more dangerous and expensive and politically messy.

Some charge that the Bush administration is using the futuristic promise of hydrogen fuel-cell cars to do nothing about the gas-guzzling and emissions of the bigger, heavier cars popular with Americans.

Others argue that even if hydrogen fuel-cell cars could be viably manufactured and marketed, they could end up creating more greenhouse gases and actually exacerbate global warming if the hydrogen used in the cars is derived from fossil fuels. Meanwhile, Japan and Europe look poised to derive hydrogen from renewable energy sources before the United States gets around to it, given our lack of federal commitment to solar and wind.

And even the growing popularity of hybrid cars, which use both internal combustion and electric motors to get upwards of 45 miles per gallon, haven't persuaded American car manufacturers to support the new technology. In tune with Bush's pronouncements, Detroit says it is committed to making the hydrogen dream a reality -- some day decades from now.

-- Katharine Mieszkowski

Google, Google everywhere

Reviewing the year in technology, it's hard to find a single month in which Google did not broadside both its critics and its fans with another eyebrow-raising initiative.

Looming over the entire year was the much awaited Google IPO, which finally got off the ground on Aug. 18. Depending on whom you talked to, that IPO either signified the return of the tech boom, gave Wall Street a slap in the face, or marked yet another greedy attempt to cash in by unrepentant dot-commers. The original pricing of the IPO was seen as something of a disappointment, but six months later the stock is doing quite well, thank you, even as Google insiders have started to cash in.

The strong stock performance might have something to do with the relentlessness with which Google keeps pumping out offerings. At the beginning of the year, the company debuted Orkut, its entry into the social networking sweepstakes. Then came Gmail, Google's free e-mail service. In October, it was time for Google desktop search which really does make searching your computer as easy as searching the Web. And to close the year off with a flourish, in December Google announced that it would pay for the scanning, digitizing and uploading of millions upon millions of books. Google is on the march; it is a search engine company no longer -- now it is a force, not exactly of nature, but of something.

When any individual or company becomes that omnipresent and all-knowing, there's usually justification for wariness. At Salon we've been pulling for Google since the very earliest days, because we have consistently found the company's offerings incredibly useful and because we believe that the executives of Google are sincere when they say they want to do the right thing. But if a different crew were running the Google ship, and economic circumstances began to force their hand, it's chilling to think of just how much information Google knows about us. It knows what we search for, whom we e-mail, who our friends are, and soon, what books we like to read. That's quite a dossier, and it's scary.

Then again, the 21st century is already replete with corporations screwing over their customers, employees and shareholders. So far Google hasn't, and once in a while it is fun to be a fan of a technology company instead of a critic. May 2005 be just as fruitful as 2004 for the company that just won't quit.

-- Andrew Leonard

Shares