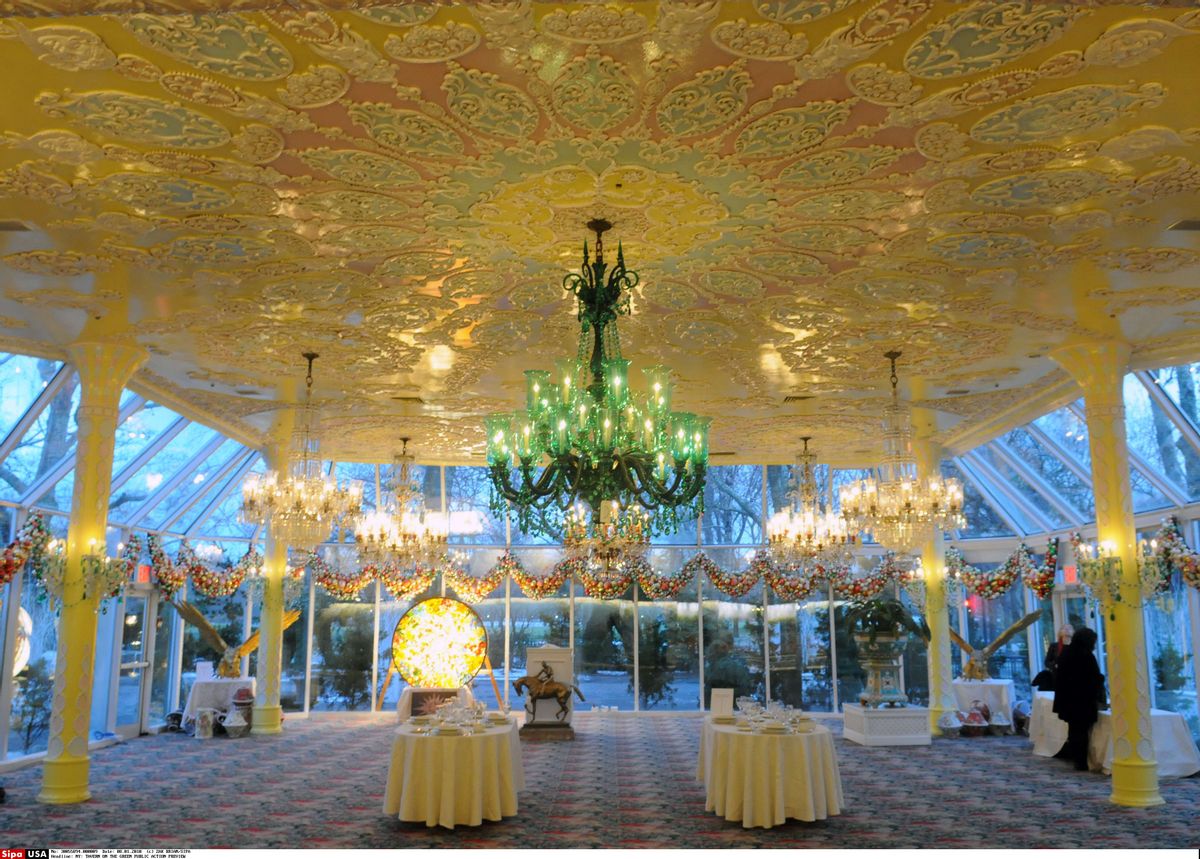

The year-round Christmas lights are off; the topiary of King Kong goes ungroomed. The closing of Tavern on the Green, an outlandishly flamboyant restaurant in Central Park with famously awful food, might seem to be notable only to students of the New York restaurant scene. And yet, day after day, I find myself reading about its history, its bankruptcy, and now, the auctioning of its property. People are coming out of the tri-state woodwork hoping to land some of the most outrageous décor pieces since the tsars stopped dropping acid. Some of them, maybe many of them, are building homages to the restaurant in their homes. With fandom like that, I knew I had to see the restaurant at least once, even if it meant crashing the auction. I had to find out what inspired such loyalty.

Over 33 years, the New York Times reviewed Tavern on the Green five times. Not once did it earn more than one star on a scale of four, and twice netted what is usually a career-killing goose egg. It did, however, earn some real low-light comments. In 1976, Mimi Sheraton savaged the baby in its cradle. "Only a few of the simplest cold dishes can be considered decent ..." she wrote, and somewhat more perkily: "There were other disasters here, among them a pasty veal chop en chemise, an esthetically offensive creation ..."

Even when the restaurant got the food right nearly 20 years later, Ruth Reichl still despaired, "Looking around that fairyland of lights, I felt a surge of rage. To thousands of visitors, Tavern on the Green is New York ... does it really have to be such a blatant example of our famous rudeness?"

And yet, despite consistently awful reviews, Tavern on the Green did incredible business. Fifteen hundred people dined under its chandeliers every day, glad-handed by owner Warner LeRoy, a man whose taste in suits would make Liberace blush, and whose father produced "The Wizard of Oz." In its best year, it topped $38 million in revenues.

"You have to remember that restaurants had a very different function in people's lives 30 years ago," Reichl said to me over the phone. "They were much more special occasion places. LeRoy's genius was knowing that people really wanted to go out for something that did not resemble their homes at all. And they loved the outrageousness of it, the theater of it. He did it like a Hollywood bar mitzvah, a Long Island wedding, that kind of celebration. It was very unabashed. And even if you knew it was awful, you'd walk past all those glittering lights in the garden and think, 'I want to be in there.'"

Clark Wolf, a longtime food and restaurant consultant and a member of Salon's Kitchen Cabinet, also credited some of Tavern on the Green's success to its place and time: "Part of it is the magic of Central Park. Remember, for many years, Central Park was a scary place. Basically, you had the Tavern, and if you went in any further, you thought you were going to be murdered. It was a little bit like the urban version of the glass observation thing over the Grand Canyon, a tourist's view into the abyss."

But it was more, obviously, than that. Wolf continued, "It was a special occasion place, but even with all the celebrities, it was never exclusive. Successful restaurants create a sense of exclusivity, but then pierce the scrim when you get there and make you feel welcome. Then you're seduced. It was like a party. There was no way you could behave incorrectly at Tavern, because you could never be more ridiculous than the place itself. It's not a White House state dinner. It was kind of a goofy place. And Warner was the perfect frontman, wrapped in taffeta and topped with sparkling lights. And that was just at lunch! Everyone could love it, drag queens and their aunts from Ohio. In New York, a successful restaurant makes you feel like you're very much in New York, or very transported out of it. Tavern was both -- there was nothing more New York and nothing more Mars. I never had a good meal, but I never had a bad time at Tavern on the Green."

I arrived at the restaurant, where auction attendees spilled out of cabs, speaking Russian, Spanish and Jersey. No one came, as would have been customary when dinner was being served, in horse-drawn carriages.

I walked through the sprawling restaurant, past the life-size statue of a bear that looked as if wailing in sorrow, and noted the items for sale. Pots, pans, a copying machine, the mundane mixed in with LeRoy's custom suits, my favorite being the one seemingly cut from the patio furniture of a Florida retirement home. There was an entire table devoted to a collection of bronze animal heads. Where in a restaurant would you find use for a collection of bronze animal heads? Say what you will, but the imagination that went into this place was ... special.

I met John, a bidder, while he was ducking his big frame into a crystal alcove, making notes on the auction schedule. "I used to work near here, for Channel 7," he told me, his voice clear and heavy. "We used to have our Christmas parties here."

"Once," he continued, "my wife and I wanted to experience something, something really New York, you know? It was a spring night, the bar was open on the patio. They had music. We danced. It was nice," he said, in that way that makes you realize that sometimes, calling something "nice" is calling it the most important thing in the world.

"I came last Friday to say goodbye, and I just couldn't. So my wife and I, we came back to take pictures. And I'm here today."

As he spoke, a woman walked by, calling out something to him. They shared a laugh. "We met yesterday; she was looking at buying some things," he told me. "It's heartbreaking."

Later, in a hallway lined on both sides with beveled mirrors that give you the giddy, innocent illusion of being the only person in the world, I nearly caught a woman ready to faint with despair.

"I'm so sad, I can't even stand it!" the woman moaned. Barbara was here simply to be in this place one more time. She was dressed prettily in pink, looking far younger than her 72 years, but her shoulders slumped, giving her a rounded, worn look. She listed a bit in her walk, and I, feeling more than a little inappropriate, asked her to speak with me. "Do you live in New York?" she asked me.

"Yes," I said.

"How long?"

"Eleven years."

"I've been here since 1965. Maybe you don't understand, but this is the place where you had every major event in your life. For every New Yorker: weddings, proposals, birthdays. Your boss would take you here for lunch if you'd done well. I mean, look at this hallway. You had the essence of a special occasion, just walking through here." She trailed off.

"Oh, Jesus! Shit!" she blurted. I fought the urge to take her arm. She was quivering. "Oh fuck it! That's the title of your article! Fuck it!" she spat.

"I had two marriage proposals here," she said. And then she asked, gently, to be left alone, and for me to write the story that this place deserves.

As Barbara and I spoke, I saw another writer, scribbling furiously in her notebook, as a woman led her through the hallway. "And I was originally booked to be married in this room," she said, turning the corner.

I took a seat in the grandest of the dining rooms, where the auction was, and where there was little sentimentality. The auctioneer had a clear, pleasant voice, but I suddenly felt uncomfortable, watching the process of liquidation. I thought of the photo I just saw of LeRoy in the hallway, in his epically ugly suit, arms outstretched as if to offer you the whole world, and I felt a sadness watching all this showiness, all this excess, all this strange passion melt into a steady, banal stream of numbers. Twelve hundred is bid ... is there a 13? Do we have 13? Bar stools, silverware, piece by piece Tavern on the Green fell away, until they'll get to the murals and the King Kong topiary, the arcs of ornaments that look like fruit crowns worn by 80-foot-tall Carmen Mirandas, and soon all that will be left will be crews of movers, and then just the memories of the Johns and the Barbaras.

On my way out, I struck up a conversation with a woman leaving with a copy of the menu. She was married there two years ago, and I realized that this was the woman leading the other writer around. "It's like the Brooklyn Bridge, an institution of New York," she said. "I'm glad I got to say I got married at Tavern on the Green," she said. "It was always a party. You always met interesting people there."

Shares