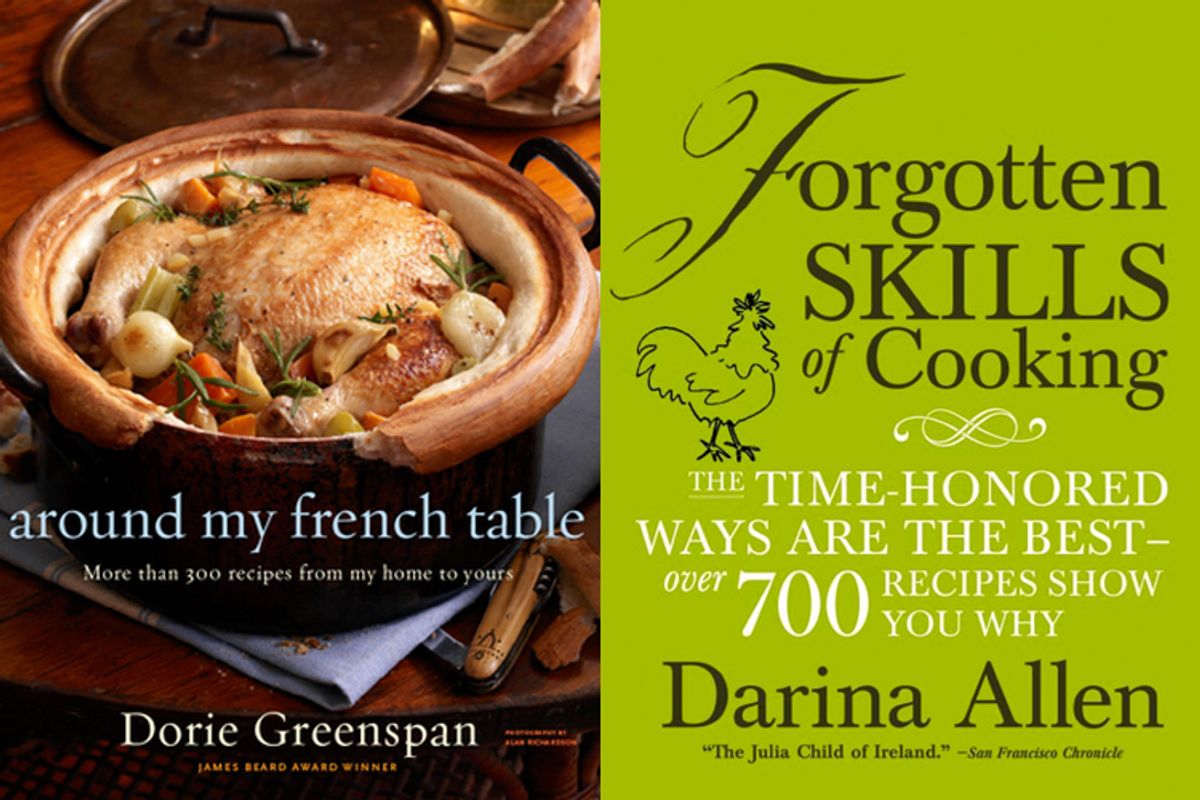

You know that moment in your cartoon life where an angel pops up on one shoulder and a devil on the other? Choosing between Darina Allen's "Forgotten Skills of Cooking" and Dorie Greenspan's "Around My French Table" is a little like that, only on one side there's an angel with a wand tipped with a butter cookie, and on the other there's a second angel, but the kind that finds you, like a biblical Jacob, to wrestle you through the night until you emerge exhausted, possibly injured, and all the better for it.

At first blush Darina's book -- a big book -- on the utterly unhip traditional Irish kitchen seems like a tourist family in bikinis: way TMI for most. But coming from a woman who runs one of the most heralded cooking schools in the world, one that produces the ingredients its students cook with, the cultural Irishness of these lessons quickly falls secondary to how fundamental they are to dealing with food -- honest, real food.

So the book is about the basics. I don't just mean pickles and bread and butter and charcuterie and what to do with produce you've never heard of before, though it is about all that. I mean, really: the basics. I dare you to show me a cookbook published in your lifetime that includes a headnote like this: "This recipe is especially worth noting for those whose kitchens don't have an oven ..." And if you can dig that one up, how about one with a page on how to turn that loose goose wing you have left over into a feather duster? Preceding that is a handy guide on raising ducks, including an answer to the question that all duck-raisers must one day look in the mirror and ask: "Do I need a drake?"

But I'm not making fun: I was stunned by the photo of that goose wing. All of the photography in this book is stunning, but it was this picture that made me understand the power of what's going on here. The image -- of a hand reaching out to clean a hard-to-reach corner with the winged feathers of a bird you have fed your family with -- is so beautiful, so clear in its vision of a perfect world. Not "perfect" as in "flawless," but "perfect" as in "complete." It's a world where the small things matter, where how you interact with food is not simply cooking and eating, but rather conducting your life with intention, diligence and a thriftiness that comes from respect.

I have friends who have gone to Darina's Ballymaloe Cookery School, and they can attest to her integrity and insistence on quality -- something you hear all the time about great chefs. But have you ever heard a great chef say this?: "If in doubt, just have a small taste. A piece of meat that smells a little high might just need a wash." Think of all the times you've come across the mantra, "You can't make great food without great ingredients." Here, Darina says something else. She says all food is great, even when it is no longer great. She is a serious advocate for the local and organic and Alice-Waters-beautiful, but she lives so firmly in the real world it seems unreal. I write on the Internet for a living, where words seem to fly away the moment they appear. I try to find out about my dearest friends in weekly five-minute glimpses at Facebook. I hope, one day, I can be as grounded in my food as this book is.

I cooked from it. The griddle bread, which is the recipe for ovenless souls, is a pretty good way of having bread on the table in a half-hour. Mine came out a little undercooked because I had no way of knowing how to check for doneness. It's a quirk of the way some of the recipes are written: with a slight vagueness that comes from the confidence that you'll figure it out. Which is not to say that they don't work. A beet-and-ginger relish followed to the T was just lovely, eat-it-straight-with-a-spoon stuff. A curry zucchini soup was also lovely, though I guess it's normal to eat that straight with a spoon.

But, to be honest, to me the recipes are really secondary to the fantasy the book inspires of putting my hands on dough and my fingers in the ground, not because it's pastoral and pretty, but because it's hard and time-consuming and difficult and honest. It's an aspiration to the right life, of being concerted and diligent and happy for doing things the right way. This book is like the friend who makes you want to be a better person. I wish we could all have those friends.

Dorie's book is about a different kind of satisfaction: one of unconditional warmth, about the friend who can watch you totally screw something up -- a batter, a project, a decent relationship -- and still be there with a smile and a bowl of rice pudding for you. (Or a fluffy mashed potato pancake.)

Cooking from it was a joy; the fresh tuna, mozzarella and basil pizza was both chic and comfortable, like dressing up for an evening in your living room. The milky roundness of the cheese and the tuna's silky texture blend into one another alongside crisp, dissolving bites of puff pastry ingeniously flattened to a crust. The unexpected beet salad dressed with lime juice, honey and dill brings earthiness outside for a little afternoon in the sun. And I was proud to serve the rice pudding to the greatest lover of rice pudding I know.

This isn't a cookbook of French cuisine, exactly, but rather a highly personal collection of recipes, many from Dorie's Parisian friends and neighbors. It's a document of decades of cooking for and with loved ones, and it shows. Every time I looked up a recipe I ended up reading the next four, because I loved living for that moment in her little neighborhood. It helps that she has fabulous friends: the tuna pizza is from Yves Camdeborde, whose restaurant, Le Comptoir, has lines at the door so long they look like a French labor strike. The Parisian "gnocchi" recipe (really poached pâté à choux!) from her friend Paule that came to her labeled as "a Caillat family classic" turned out to be from Le Cordon Bleu. That's some family.

If there is any truth to the idea that one writes like one is, it's obvious why Dorie is such a charmer. Her sketches of friends and neighbors, however long or brief, read like a smile feels. In one, she chides, ever so gently, a friend who downplays her own creation, a Francophone ceviche. "It was a brilliant mix," Dorie writes, "but in typical Meg fashion, when she sent me the recipe, she called it 'Strange, Made-Up Winter Ceviche,' a witty name that shortchanged both the recipe and her culinary imagination."

Elsewhere, she tells of being condescended to, and then ignored, by a grumpy butcher. It's an anxiety-inducing story, one painfully familiar to anyone who's ever been suddenly reminded that you don't really belong somewhere. Later, she finds that the butcher was unwilling to help her because she was asking about a "lost" recipe, and then her attention shifts to consider the notion of perfectly delicious dishes being forgotten. It's a turn in the story that speaks both of an intellectual curiosity and a generosity of spirit. I'm still trying to get over the old bastard who cut me off in traffic in 2003 to tell me to "go back where I came from." (Though I do have to hand it to him. When I stooped to his level and told him I was born in New Jersey, he yelled back, "Born? With that hair you look like you were hatched out of a goddamned egg!" Which, really, was a genius put-down.)

So, which of these books do I pick? Really, the more important question is which of these you'll pick, and the best thing for you to say would be "both." For me, honestly, it's a completely subjective matter of personal timing. There are times when you want to push yourself, to submit to the fact that discomfort is the nature of learning, and there are times when you just want a mug of warm milk and to have someone say that everything is going to be OK. When I was reading "Around my French Table," I came upon this: "Michael likes it to be flawlessly smooth, the kind of smooth you can only get if you're profligate with the butter and carefree with the cream." Profligate with butter. Carefree with cream. I stopped to read those words again, aloud, because they're the sound of what I want to hear from the world right now. And so I am glad to take a seat at Dorie's table.

Shares