You wouldn’t want to tangle with Tom Gannon. When I look at Tom, I end up imagining his ribcage, which must be massive, like the stays in the hull of a galleon. He has a wide chest and meaty arms scrolled with tattoos: on one arm, a full sleeve of roses against a black background; on the other arm, a giant Ganesh winks from a swirl of peacock feathers and smoke. Tom is tall and balding with a neatly shaved head, a red goatee dusted with white, and no-nonsense blue eyes. But in the end, his fortress-like demeanor stems not so much from his appearance as from his attitude.

Maybe it’s the Jersey. Tom’s dad was a New York cop, and his mom worked full-time as a nurse, yet somehow found the time to give four boys a good Catholic upbringing. “It was different in the city,” Tom remembers. “We were surrounded by family and other people who had tons of kids. Childcare was not an issue.” When Tom was 9 the family moved from the city to River Edge, N.J., where they lived in a close-knit neighborhood Tom describes as “very Irish and Italian, with some token Protestants.”

Listening to Tom talk about his family is like watching a nostalgic movie about growing up on the East Coast — one of those films that begins with a rueful voice-over as the camera pans in on the old neighborhood. Tom is not sure when his ancestors emigrated from Ireland to New York: “We don’t know. My father’s generation was the first generation that was literate. No one could read. I don’t think anyone kept track.” He describes his family as close; they ate dinner around the table every night (classic stuff: meatloaf, spaghetti with meatballs, roasted chicken), watched the game together and took care of their own, no questions asked. When I ask Tom if he can pinpoint a family philosophy, he answers immediately: “The philosophy of my family is family,” he says, and laughs a little as he unloads a shopping bag full of onions and canned tomatoes.

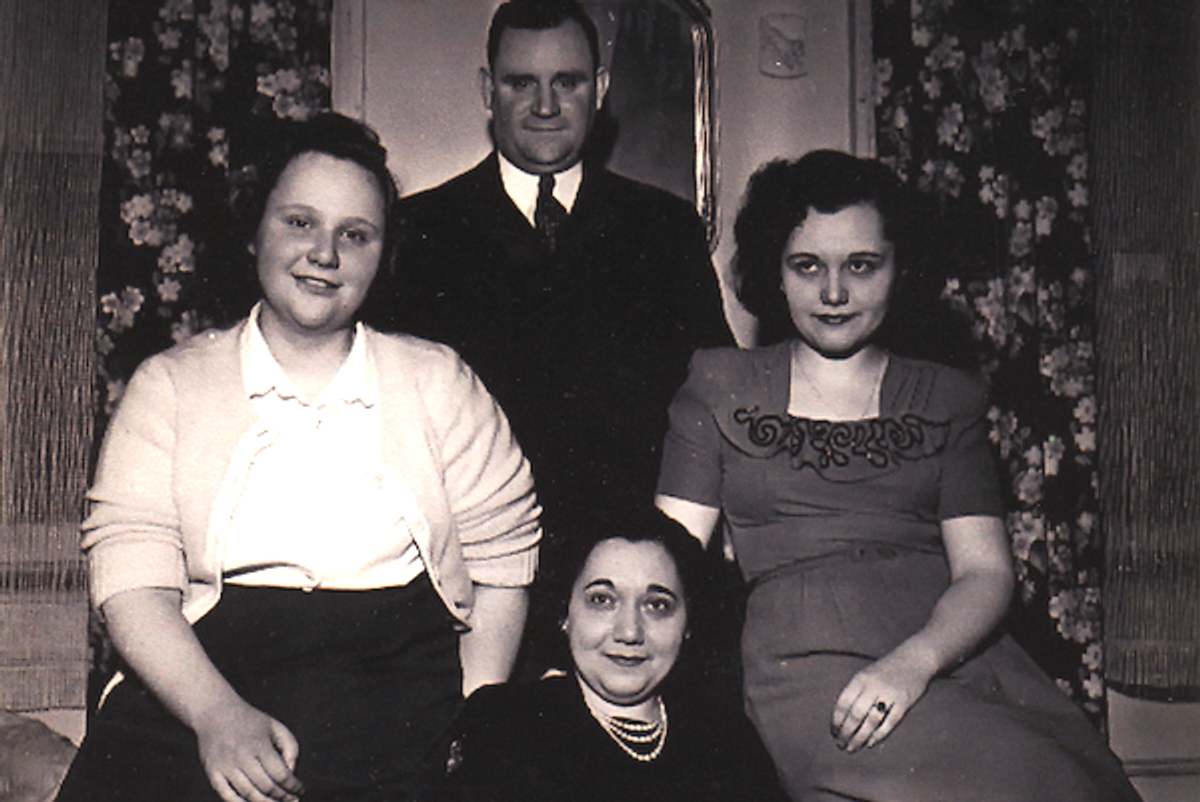

Tom’s chicken Parmesan recipe comes from his great aunt Rosie, who caused a huge family scandal when she married Tom’s great uncle Frank in 1914. Frank was 16 and Rosie was only 14, but the scandal had nothing to do with age. Tom’s densely Irish family disapproved of Frank marrying an Italian. “Their generation was, of course, very bigoted,” Tom remarks, rolling an onion onto the cutting board. “By the time my father’s generation rolled around, it was much more common. Some of my dad’s best friends married Italian women and nobody cared. But back in Rosie’s day, it was different, it was a huge deal. Until they got married — then you couldn’t say anything.”

Rosie and Frank moved into an apartment above Frank’s brother’s funeral parlor in Gramercy Park, where they would live for the next 70 years. As soon as Frank married and the family realized they were stuck with Rosie, everyone shut up about the Italian issue. “As a matter of fact,” Tom says, “she became like the most popular person in the entire family. I mean everybody loved Aunt Rosie. She was very gregarious. She was very opinionated. She liked to complain a lot, but in a funny way.” When I ask him what she looked like he says, in his thick Jersey accent, “She looked very stereotypical. She had a wide nose and hair like steel wool. Very sad eyes, kinda baggy, like some kind of basset hound or something like that. She liked to eat,” he adds, slapping his gut. He remembers Rosie pinching the kids’ cheeks, drinking Seven and Seven and “a fair amount of wine,” and cooking constantly, until her classic Italian-American recipes were adopted by every household in a proudly Irish family. In fact, half of Tom’s favorite family recipes are Italian-American.

To make Rosie’s chicken Parmesan, Tom starts with the sauce. He shows me a neat way to peel a large quantity of garlic cloves: Put the unpeeled cloves in a lidded cook pot and shake vigorously. I’m amazed to see that half the cloves are peeled in the first rough shake; after a second session, all the cloves are skinless. He throws the garlic in with the onion, which is already sautéing in a cast iron pan. “This is about how you want them to look,” Tom remarks, gesturing to the pan full of translucent golden onions. He dumps two cans of whole tomatoes into the pot and mashes at the mixture with a potato masher.

Despite making a huge mess in the kitchen, Tom is not a haphazard cook. He takes his time as he slices each chicken breast into cutlets, and then dips the meat in eggs and bread crumbs. He’s a more precise cook than I am — his every motion betrays the typical New York obsession with exact culinary tradition. When I suggest we could use a preexisting bag of panko to coat the chicken filets for the Parmesan, he looks horrified. “No,” he says decisively. “We need the cheap stuff.”

While he’s making the Parmesan, he’s instructing me on how to make another family specialty, Uncle Frank’s meatballs. When I start rolling the mixture of pork, beef, eggs, panko and spices, he views my handiwork with a dubious expression -- it’s clear that my meatballs are neither small enough nor round enough for Tom’s taste. When I later offer to help fry the chicken fillets for the Parmesan, Tom doesn’t allow me to bread the cutlets myself -- he does it for me, and then hovers behind the stove to make sure I’m letting the cutlets get crispy enough before I flip them.

Tom’s concern doesn’t come across as fussy — he’s just the type of guy who likes to do things right. It makes me think about the difference between East Coast and West Coast culinary culture. I come from a culinary tradition that is primarily focused on innovation and substitution. “Sure, that’s good, but how can I make it with nettles?” Tom’s background is more old school — recipes were passed down from generation to generation, and changing things up was more likely to be viewed with horror than with admiration.

But Tom’s family story isn’t all about staying the same. During the course of our conversation, Tom affectionately describes his family as square and later says his parents were “straight as a pin.” The same could hardly be said for Tom: He says he always felt a little different, never liked suburbia or really bought into the whole Jesus thing. When I ask him how he “was led astray,” he laughs and answers: “rock 'n’ roll”. After a deadhead phase, Tom moved to Seattle, where he fell in with a group of friends that reads like a who’s who of the grunge era. His family back home didn’t know much about his Seattle life. “They never saw my tattoos for years,” he says, taking a sip of beer and meditatively stirring the red sauce. “In those days I only went home for Thanksgiving, and I always wore long-sleeved shirts. I didn’t know how long I could keep it going, but I always figured as long as I could keep it going for that Thanksgiving, I’d be fine,” he laughs. “But then I got real sick with pneumonia — it was around 1998, and my lungs stopped working. I was in a coma. My parents flew out. They thought I was dying. That’s when they first saw my tattoos — I’m lying in a hospital bed, totally inked, and they’re like ‘what the hell?’ But I never got a lick of shit for it, because I lived — suddenly me having tattoos didn’t seem too important to anybody. Never any discussion about it — to the point when my mom eventually even started thinking she wanted a tattoo herself.”

Despite their dramatic tattoos and stereotypically West Coast behaviors (Tom manages the recycling program for the city of Seattle, his wife Becky eats organic) Tom and his wife are pillars within their East Coast family: In the summertime the entire extended family vacations in the Adirondacks, where Tom and Becky’s son Jack runs wild with his Jersey cousins. I hear shades of Aunt Rosie in Tom’s story, and both tales remind me of something that’s been on my mind lately: When we are forced to accept Italian Aunt Rosie or tattooed Uncle Tom or gay cousin Doug, we become a little less likely to jump to conclusions and, more often than not, our realities are enriched in untold ways. (In a best case scenario, this enrichment appears in the form of cheese-coated chicken cutlets.) On a grander scale, the way we are forced to evolve as families plays out in the way we see the world and the way we change as a nation.

But perhaps I’m getting too high-minded — when I’m sitting in the glow of candlelight spooning Aunt Rosie’s chicken Parmesan onto my plate, I’m just happy. The sauce is tangy and simple, the chicken is crunchy and coated in gooey cheese, and the company is solid. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Aunt Rosie's Chicken Parmesan (Serves 6)

Ingredients

- 1 package spaghetti noodles (cooked, still hot)

- 6 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 onion (chopped)

- 3-4 garlic cloves (chopped)

- 1 32-oz can whole tomatoes

- ½ cup red wine

- 1 bay leaf

- 1 tablespoon fresh oregano (minced)

- 1 tablespoon fresh basil (minced)

- 1 teaspoon sugar

- Salt to taste

- 2 lbs chicken breasts (sliced into ½-inch thick fillets)

- 2-3 eggs (beaten)

- 1½ cups bread crumbs

- 1 small zucchini (sliced)

- 10 ounces baby spinach

- 1 tablespoon butter

- Mozzarella cheese (sliced)

- Grated Parmesan

Directions

- In a large pan, heat 3 tablespoons of olive oil and sauté onion over medium low heat for 5-6 minutes. Add garlic. Continue to cook until onion is translucent. If necessary, turn heat down.

- Add tomatoes, wine and bay leaf. Break up whole tomatoes as you stir. Simmer sauce for 30 minutes. Add water or stock if necessary.

- Add spices, sugar and salt to taste. While sauce continues to simmer, slice chicken breasts into cutlets and preheat oven to 350.

- Dip cutlets in eggs and then in bread crumbs. Brown cutlets in olive oil. When one side is thoroughly brown, flip and fry the other side.

- While cutlets are frying, add zucchini, spinach and butter to sauce. Cook for a few minutes and remove sauce from flame.

- Cover bottom of baking pan with sauce. Add chicken. Cover chicken with mozzarella and additional sauce. Bake in oven for 15 minutes.

- Serve over spaghetti with Parmesan cheese.

Shares