For me, it went like this: If you are pulled over in your car, keep your hands on the steering wheel. Give the officer your license. If your registration is in your glove box, tell the officer that you’re going to retrieve it from there, and move slowly.

If you are stopped by an officer while you are on the street, keep your hands visible. Don’t say anything besides “yes” and “no.” Be compliant. Be polite.

This is “the talk.” Most African American and Latino kids get some version of it as soon as they are old enough to go out on their own.

Mine came from an adult mentor at a youth newspaper that I wrote for in high school, but only after a friend and I had been harassed by a police officer in a wealthy suburb.

We were driving there for a holiday party hosted by one of the publication’s benefactors as a treat for the paper’s teenage reporters. My friend was driving under the speed limit, didn’t run any lights and used the proper turn signals. We got pulled over anyway, and we knew why. The officer let us sweat it out in the car, then gave us back our identification.

He didn’t arrest us. He didn’t have to. We were shaken and demoralized and knew we would never go back to that neighborhood. That was his intent.

That incident happened decades ago, but the fact that an entire documentary has been constructed around this ritual speaks to the timelessness of this distressing issue.

One could argue that “The Talk – Race in America” airing on PBS member stations Monday at 9 p.m., feels both right on time and slightly too late.

Lawmakers in several states have created bills geared toward criminalizing protest; if they pass, people of color stand to be disproportionately impacted. North Dakota lawmakers wants to make it easier for drivers to escape prosecution if they run down protesters with their cars. A bill in Minnesota, where Philando Castile was shot and killed by police in July, would turn unlawful assembly on a highway into a gross misdemeanor carrying penalties of up to $3000 in fine and a year in jail.

In November a Washington state senator spoke of introducing a bill that would allow protesters to be charged with committing “economic terrorism.” And on Feb. 9, Donald Trump signed three executive orders related to law enforcement that were mostly for show but telegraph the falsehood that people in the inner cities are combatants as opposed to citizens in need of protection.

Watching “The Talk” may put some of this into context.

The aim of “The Talk” isn’t merely to discuss what the talk is but why it exists and continues to be a necessary coming of age ritual in the United States. The underlying issues that perpetuate the troubled relationship between minorities and law enforcement are much broader and more complicated than a two-hour documentary can exhaustively address.

At the same time, two hours is enough for people who don’t necessarily feel have to worry about losing their lives in an encounter with police to understand the frustration, fear and anger at those who do.

“The Talk” was filmed in cities around the country, using personal stories to begin to grasp the difficulty of the debates swirling around police brutality and the rise of community movements such as Black Lives Matter.

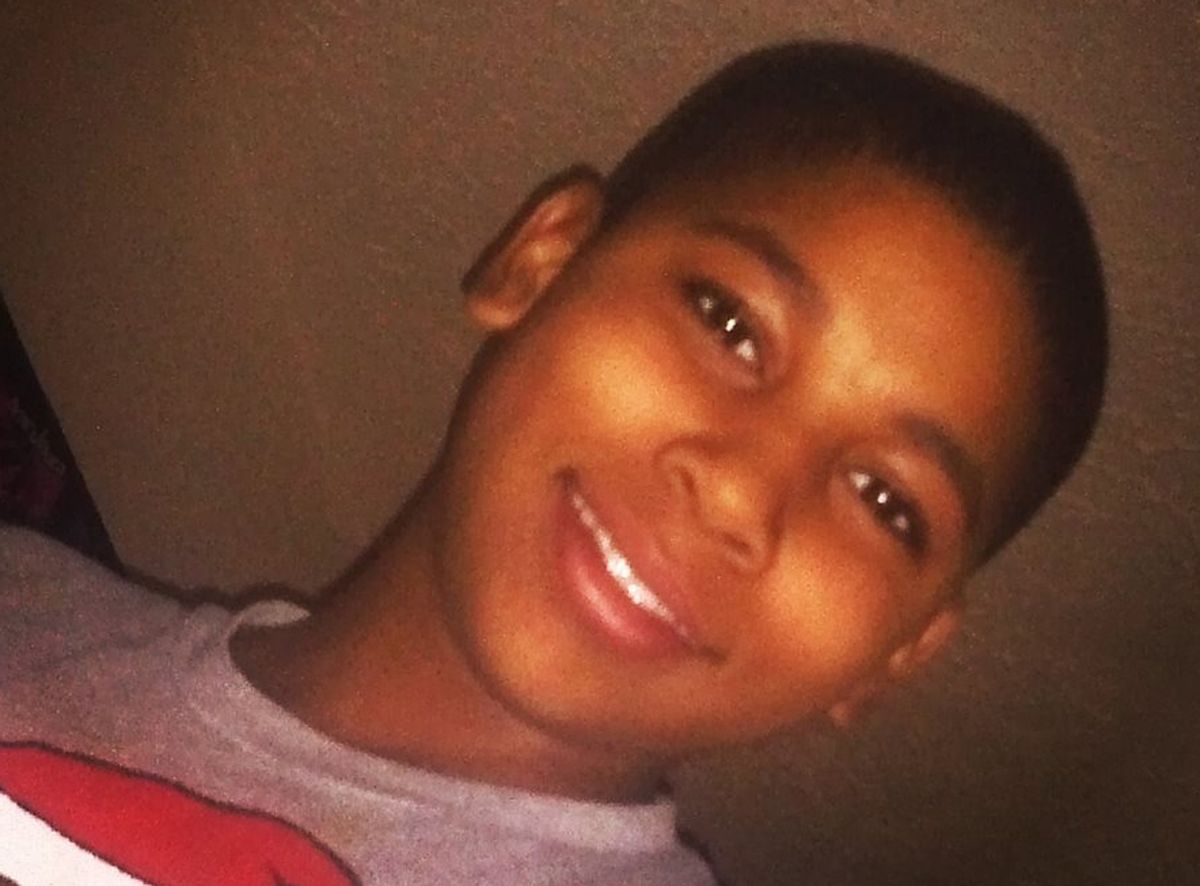

Some of these are stories with which we’re depressingly familiar: Audio of the 911 call and video of the shooting that claimed the life of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, a boy playing in a park with a toy gun, opens the Cleveland-set first segment. From there “The Talk” ventures to Paramount, California, where a Los Angeles County sheriff shot and killed 28-year-old Oscar Ramirez, who was unarmed.

“The Talk” also speaks with law enforcement officials and takes viewers inside of the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy to see trainees in action, and get some sense of what dangers officers face during routine calls.

The documentary filmmakers present perspectives from both the law enforcement and minority communities with great sensitivity. Never does “The Talk” let the audience forget that the people working in law enforcement aren’t a monolith, and the majority of officers take pride in protecting law-abiding people desiring safer communities.

And yet, “The Talk” also touches upon the historical and cultural problems that continue to feed the adversarial relationship that people of color have toward the police. One of the most powerful segments shows Catherine Brown, a Chicago pastor who worked for years as a community advocate working to build a bridge between local law enforcement and her neighborhood’s residents. She asked members the local police force to share information with her community in order to know what to say and do to be helpful to officers.

All of that came in very handy when a pair of cops assaulted Brown in front of her own home, the video of which is shown in the documentary.

There is no interviewer featured in “The Talk”; rather, its allows subjects simply share their own experiences as how those moments inform their various points of view, leaving the audience to draw their own conclusions from what they’re seeing.

Yes, Tamir Rice was holding a replica of a pistol that did not have an orange safety cap that would have let the officers know it wasn't real. Yes, the 911 caller told dispatch that it probably wasn’t real.

All Samaria Rice knows is that she lost her baby. “If you was going to ride up on him, you could have said, ‘Hey, little man, what you doing?’ You didn’t have to shoot him,” she says in “The Talk.” But this speaks to a much larger problem. Samaria thought the world would see her 12 year old son as she sees him — a kid, her “little man.” The officer that shot him initially thought he was 20, which may have made him seem to be more of a threat (a cultural and occupational bias confirmed in a 2014 study conducted in by the American Psychological Association).

The documentary doesn’t say any of this. It's enough to simply show it. The power of “The Talk” comes in allowing a person to absorb these powerful images and testimonials and perhaps have a better understanding of frustration that’s led to people taking to the streets in protest.

And no person of color is immune to living with these fears. Actress Rosie Perez, “Black-ish” creator Kenya Barris, hip-hop artist and activist Nas and director John Singleton each share their perspective during interstitial segments.

New York Times columnist Charles Blow shares the story of his son having been held at gunpoint. He was exiting a campus library when an officer stepped up to him, gun drawn, and told him to get on the ground. Only then, says Blow, did the officer ask him for his name and whether he was a student.

It was the first time Blow’s son had ever had a gun drawn on him. And it happened at Yale.

“You’re angry because the historical precedent is that too many of us have encountered the exact same thing,” Blow says. “And you see it tumbling forward into another generation, and you realize that you are powerless to stop it.”

Blow’s account reminded me of the second part of that talk my mentor gave me all those years ago.

Even if you observe all of these rules, even if you are doing nothing wrong, he said, your nice clothes, proper etiquette and crisp diction will not save you. Your upbringing in a well-to-do neighborhood will not save you. Your proximity to your white friends will not save you; in fact, that may make you more of a target.

The need for “The Talk” is not going away any time soon.

Shares