In mid-May of 2017, Robert Lighthizer, the new U.S. trade representative, came to Vietnam for an APEC ministerial-level meeting. Lighthizer had a friendly and engaging manner, but his visit was a disaster in terms of substance. The Vietnamese, other APEC country representatives, and the U.S. business community were stunned by the arrogance of his remarks and his willingness to sabotage an international trade agenda in favor of an "America First" approach. By this time, a visit to the United States and a meeting with President Trump at the White House had been planned for Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc.

When the prime minister arrived in New York City on May 30, U.S. investors in Vietnam — including the businessman Phil Falcone (my Harvard classmate and one of the biggest U.S. investors in Vietnam) and Kurt Campbell, one of his advisors — welcomed Phúc and his commercial delegation at a star-studded investor gathering at the InterContinental New York Barclay hotel. At the event, incentives and opportunities for doing more business with the United States were highlighted, and Phúc promised that by 2035, 30 percent of Vietnamese citizens would be members of the middle class. He touted Vietnam's reforms and its upgraded credit ratings and pledged that the country would increase its purchases of U.S. exports. American investors were impressed.

I accompanied the prime minister on his flight from New York to Washington. He ambled back to my seat on the plane to ask how he could best engage with President Trump. "Be yourself," I urged him. "Use visual aids, but don't rely too heavily on notes." Maps would be good, too, I suggested.

In time for Phúc's visit, U.S. companies had completed more than $8 billion worth of commercial deals, mostly for high-tech products — including almost $6 billion worth of sales for General Electric. In Washington, the prime minister was joined by Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross in a ceremonial signing of the biggest completed deals.

Our meeting with Ross before the signing was particularly unsettling, however. The eighty-one-year-old secretary seemed lost, unable to find his place in his briefing notes or to determine which trade challenges to emphasize. His translator was also hapless, and we had to rely on the prime minister's. Ross focused on obscure agricultural disputes over shrimp, catfish, cheese, and drugs for veterinary medicine, all mentioned in an annex to his briefing paper. These issues were supposed to be the purview of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. The meeting with Perdue was far more productive, as both leaders enjoyed solving problems.

Phúc's meeting with Lighthizer was also useful, especially because Lighthizer had so recently visited Vietnam. That evening, at a dinner hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Lighthizer introduced the prime minister by noting that "our trade deficit presents new challenges and shows us that there is considerable potential to improve further our important trade relationship."

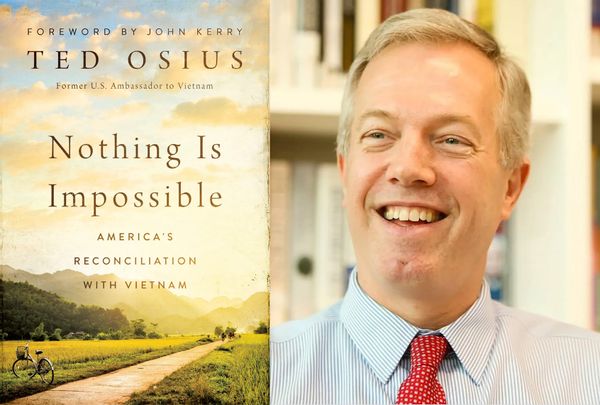

"Nothing is Impossible: America's Reconciliation with Vietnam" by Ted Osius (Rutgers University Press/Photo courtesy of author)

"Nothing is Impossible: America's Reconciliation with Vietnam" by Ted Osius (Rutgers University Press/Photo courtesy of author)

Phúc stated that Vietnam was eager to increase trade with and investments by the United States. "In terms of trade," he said, "it is absolutely realizable for us to increase our trade turnover, thus turning the U.S. into Vietnam's largest trading partner and promoting fair and equal bilateral trade relations. It is Vietnam's desire that the U.S. will facilitate the import of textiles and garments, footwear, seafood, fruits, and other products."

When I was a foreign policy staffer for Vice President Al Gore, I visited the Oval Office a number of times. As ambassador, I accompanied Vietnam's Communist Party leader to his meeting with President Barack Obama. Nothing could have prepared me for the strangeness of President Trump's meeting with Vietnam's prime minister on May 31, 2017.

The Oval Office looked the same. The wall-to-ceiling windows continued to overlook the South Lawn. The famous "Resolute" desk dominated the room. But it didn't feel like the Oval Office I remembered. In President Obama's time, rooms outside the Oval Office buzzed with activity, while the office itself was serene. Now the situation was reversed. The West Wing seemed eerily quiet. Inside the Oval Office, people scurried in and out. Deputy National Security Advisor Dina Powell and a cluster of other advisors huddled around the "Resolute" desk, where Presidents Rutherford Hayes, Franklin Roosevelt, and John Kennedy had governed. No one left to make room for the new arrivals, and the office seemed to get more crowded with each passing moment.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Standing behind a cluster of aides and attempting to get the president's attention, National Security Advisor General H.R. McMaster tried to introduce me to President Trump: "Mr. President, this is our ambassador to Vietnam."

I stared at a stiff helmet of orange hair as the president looked up and said, "You're lucky. That's a good job."

"Yes, sir, I'm very lucky," I said. "I love my job and feel privileged to do it."

"So, who are we meeting?" the president asked.

"The prime minister of Vietnam," McMaster replied.

"What's his name?"

"Nguyen Xuân Phúc," a senior National Security Council official said. "Rhymes with 'book.'"

"You mean like Fook You?" President Trump asked. "I knew a guy named Fook You. Really. I rented him a restaurant. When he picked up the phone, he answered 'Fook You.' His business went badly. People didn't like that. He lost the restaurant."

All those present laughed dutifully.

"Mr.President," McMaster interrupted, "we only have five minutes for this briefing."

More people slipped in and out. I wondered how anyone could concentrate in all the chaos. After hearing that Vietnam had a trade surplus with the United States and a trade deficit with China, the president interjected: "The Chinese always get great deals. Except with me. I did a great deal in China."

President Trump then instructed Lighthizer to "bring the U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam to zero in four years."

Lighthizer nodded, perhaps not knowing how to reply. It was an impossible task. He then tried to shift the president's focus. "The ambassador [to Vietnam] is trying to finish a deal to build a new embassy," he said. "We can have a groundbreaking ceremony when you visit."

A member of Lighthizer's staff had told me, earnestly, that President Trump liked groundbreaking ceremonies. He enjoyed holding a gold- plated shovel for the photographers.

"I'm visiting?" the president asked, apparently unaware that he had agreed to join an autumn summit of APEC in Vietnam. He then disappeared into another room.

Jared Kushner, the president's son-in-law and a White House advisor, was paying attention to our conversation about building a new embassy in Hanoi. "How much will it cost?" Kushner asked. I replied that the U.S. embassy in Beijing cost more than $1 billion. A new embassy in Hanoi might be built for less— perhaps half as much, depending on the cost of the land.

"$500 million?" Kushner seemed surprised. "that's a lot. Why are we spending so much? If we're going to give them that, we should get something back."

I wondered if he understood that we were trying to build a new embassy for the United States and not for Vietnam. "Our current leased space is dilapidated," I told him. "It was supposed to be temporary twenty-two years ago. It's not safe. A truck bomb could drive right up to it and blow us up in a moment. Like in Benghazi."

Kushner had already formed an opinion. "If they're going to get that [embassy]," he said, "We need something in return. Tell them we'll build it if they bring our trade deficit to zero."

I repeated my argument about security for American citizens, but Kushner's dark eyes had shifted elsewhere. He was no longer listening.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Ushered out of the Oval Office, I stood in the hallway and chatted with Vice President Mike Pence. He had just returned from Jakarta, Indonesia, where he had addressed the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. I told Pence that Vietnam had received his speech warmly. Smiling, his blue eyes focused on mine, the vice president demonstrated an uncanny ability to make me feel like I was the most important person in the world.

We waited while President Trump and Prime Minister Phúc met in the Oval Office "one-on-one"— with interpreters and about a hundred television and print journalists. President Trump noted that the United States has "a major trade deficit with Vietnam, which will hopefully balance out in a short period of time. We expect to be able to do that."

The prime minister showed the president a map of the South China Sea as a reminder that China's behavior concerned Vietnam most of all. The president and prime minister then moved to the Cabinet Room, where the vice president, cabinet members, and I joined them. President Trump again urged Prime Minister Phúc to reduce Vietnam's trade deficit with the United States from $32 billion to zero in four years. He also encouraged Vietnam to ratchet up its pressure on North Korea, and he asked that Vietnam accelerate its acceptance of Vietnamese refugees subject to deportation orders. I knew the source of the third request: I had seen [Steven] Miller slip in and whisper into the president's ear just as he was heading to the Cabinet Room. It was left to the prime minister of Communist Vietnam to extol the virtues of free and fair trade. He said that trade "leads to growth and jobs. Our two economies are more complementary than competitive."

President Trump spoke again about trade deficits and said, "we must make more progress before the APEC summit." The president told the prime minister that Saudi Arabia had placed orders worth $450 billion during the president's recent visit there. "Jared [Kushner] and Rex [Tillerson] worked really hard," he said. The message was clear: presidential visits came with a price tag.

When McMaster suggested that "an aircraft carrier visit would be historic and an important symbol," the prime minister replied carefully that Vietnam "appreciated the initiative to bring an aircraft carrier. When we have the capability, we'll receive it." He added, "We are not yet in a position to do so."

Vietnamese leaders needed first to gauge the Chinese reaction before committing to a date for an aircraft carrier visit. In a joint statement released following the prime minister's White House visit, the Vietnamese said only that the two leaders had "looked into the possibility of a visit to a Vietnamese port by a United States aircraft carrier."

As President Trump walked Prime Minister Phúc out of the West Wing, the group ran into Marc Kasowitz, one of the president's lawyers. Kasowitz also represented Falcone. In December 2016, Kasowitz and Falcone had arranged for President-elect Trump to speak by phone with the Vietnamese prime minister.

Kasowitz grinned when he saw the prime minister. He appeared to have been waiting outside to show that he had access to the West Wing and therefore "juice" with the current president. Surprised to see him, the prime minister smiled, his head tilted to one side.

"You know him?" the president asked, and the prime minister acknowledged that he did. Kasowitz shook my hand vigorously. "You know him, too?" the president asked me. I nodded.

After the December 2016 phone call, I had written to my bosses in the Obama administration's State Department, concerned that such a call, arranged by Falcone, showed Vietnam's prime minister that access to the new U.S. president could be bought... I never received a reply.

After a January 12, 2017 meeting in Hanoi with Kasowitz, Falcone, and a gaggle of New York real estate lawyers associated with President Trump, an embassy colleague and I had compared notes. "I feel like I need to take a shower," she said. I, too, wanted to scrub away the scent of corruption. Before meeting me, Kasowitz had asked a friend, "What leverage do we have over the ambassador? What do we need to give him to bring him onto our side?" My friend explained patiently that any U.S. ambassador has a responsibility to help American businesses succeed. No leverage or quid pro quo was needed for me to do my job.

Shares