On a very warm evening a few years ago, I walked into a cool, brisk, minimalist restaurant with heavy, wide wooden doors, sitting down at a relatively tiny table with nothing on it. The menu was as minimal as the space, but as I soon noticed, the flavor of the dishes I ate there were anything but.

Sharp, bright, pungent, robust — the multi-course Korean-inspired meal was a stunning culinary experience, but it was the dessert that really put things over the top. Burrata — a then-uber trendy up-and-coming “it ingredient” — in a dessert? “What a wild idea!” I thought, but I’m nothing if not predictable when it comes to any sort of Italian-adjacent food, so I immediately ordered it.

The burrata came with sujeonggwa granita — essentially a shaved-ice imbued with the flavors of a traditional Korean cinnamon punch with ginger — as well as walnuts, for texture, and a smattering of lychee yogurt.

It was, and remains, one of the single best desserts I’ve ever tasted. The cold granita, the crunch of the walnut, the smooth cheese, the tart yogurt, the differing temperatures, the way the granita melted on your tongue; it was truly something else. (It’s still on the menu, by the way!)

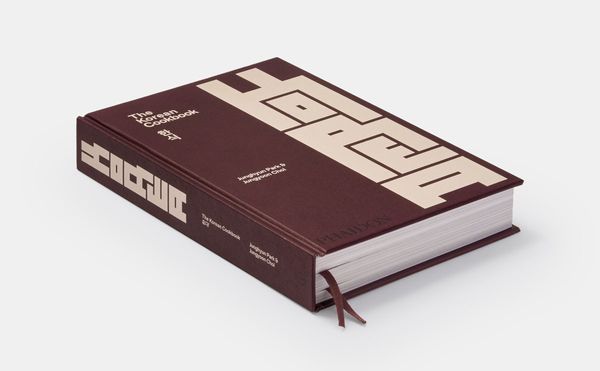

The restaurant was Atoboy and the chef was Junghyun “JP” Park, which he operates with his wife, manager Ellia Park. Since that day, they’ve opened Michelin-starred Atomix, plus Naro, Seoul Salon (all in New York City) and most recently, in October, he released “The Korean Cookbook” via PHAIDON, a stunningly comprehensive tome and love letter to everything that defines Korean food. He collaborated with culinary researcher, chef and writer Jungyoon Choi in developing and writing the book, who advised culinary research and history.

With 350 recipes and nearly 500 pages, the book is truly a compendium. It shows a chef who’s researched and trained extensively, learning every single ounce of the trade and the cuisine, utilizing those building blocks to make a mark in the New York City food scene and the food landscape worldwide, harnessing Korean staples and fundamentals into dishes and menus that are transportative and delicious while also honoring the work that came before his. As Korean food explodes in popularity, Park shows that it is not a monolith and can run the gamut from street food to high-end cuisine; Park's elevated, modern takes on cherished Korean classics and flavors blends those lines into something wholly original.

While many Americans may automatically think of Korean barbecue when the notion of Korean food comes up, or other staples like bulgogi, Korean fried chicken or tteokbokki, Park's deep focus and exploration on banchan and Hansik at large — both throughout the book and also in his restaurants — shines a light on other areas of Korean food that may not be as well known.

As Park told me, his drive to write such a book coincides with the recent immense growth of the cuisine at large. “As the interest in Korean culture continues to grow, and the limelight on Korean cuisine has grown significantly, we were interested to add to the conversation by creating a cookbook that captures the foundations of Hansik today.”

Chef Junghyun Park (Photo by Peter Ash Lee/Courtesy of Phaidon)

Chef Junghyun Park (Photo by Peter Ash Lee/Courtesy of Phaidon)

Hansik, simply defined as “Korean cuisine,” which Park aims to highlight throughout the book to encapsulate its core tenets: “None of the recipes are my own, or creative variations of existing recipes. Rather, they aim to showcase the true Hansik, the recipes of everyday people of Korea.”

As written in the book, "the common thread among most dishes is that the ratio of the vegetable ingredients to meat ingredients is 7:3. Of the ingredient used in hansik, 70% are plant-based. Furthermore, the main flavoring method in hansik is fermentation."

In addition, Hae Kyung Chung — a professor at Hoseo University whose writing appears in "The Korean Cookbook" — writes that "[Hansik] is rooted in the theory of yin and yang and the five elements, which was a defining philosiphy of the Eastern culture in understand the cosmos."

In recent years, it’s become increasingly clear that there’s a deepening interest in Korean food at large. In a 2022 New York Times article, Ligaya Mishan wrote that "In the United States alone, there are now anywhere from 2,000 to 7,000 Korean restaurants (the higher estimate comes from the marketing research firm IbisWorld) and, according to data analyzed by the New York University food studies scholar Krishnendu Ray, four times as many Korean restaurants merited inclusion in the Michelin Guide to New York in 2022 compared to 2006.”

It's not just an American "trend,” though, Mishan notes: Korean restaurants worldwide increased by a staggering 262% in the eight-year span between 2009 and 2017.Writing in FORBES earlier just this month, Laurie Wenrer gave high praise to "luxe" Gori, "a tasting menu chef's counter . . . above Anto, a high end Korean steakhouse in New York Midtown East.” With restaurants like COTE or Haenyeo in NYC, “Top Chef’ alum Beverly Kim’s restaurants in Chicago and cookbooks from Eric Kim, Maangchi and many, many more, the interest in Korean culture and cuisine — whether street food, comfort food, or highfalutin restaurant offerings — is being met.

For Park, though, the focus of this book was more homegrown: “My restaurants are ultimately very much an expression of my personal palette, my experiences and my creative ideas.”

“It stems from Korean cuisine because I am Korean and it is what I grew up eating – but the recipes and cooking at my restaurants combine my global experiences, my studies, my ideas, that are personal," Park said.

Park was intentional about the book’s appeal to Korean people at large. "Language has a powerful influence and we wanted to be able to use Korean language especially around techniques and ingredients that are distinct to Hansik." Again, he focused on the intent of the book, saying that "this book is aimed at home cooks and/or readers all over the world who are interested in learning about Korean cuisine and Korean culture, we wanted it to provide a resource for anyone interested."

We need your help to stay independent

“We spent the first year to first create the philosophy and framework of the book before delving into specific recipes," he said.

I also asked about the collaboration between Park and Choi. Choi says that "Chef JP has the perspective of a chef responsible for shaping the cultural discourse between diners, especially in a foreign city outside of Korea. His understanding of how people perceive or are interested in Korean cuisine was important in shaping the book."

In addition, Park remarks that Choi "has a truly deep and factual understanding of Korean cuisine, its history and its roots. Having led countless research projects around Korean cuisine and having produced presentations and written works around it, she has an understanding of the essence of each component of Hansik." Clearly, as they put it, it’s most certainly a “symbiotic relationship.”

Another important note within the fundamentals of Korean food, of course, is rice and banchan at large. “One of the most important or central foundations of Hansik is cooked rice, bap. Due to many historical and geographic reasons, rice was and still remains the centerpiece at any Hansik meal.”

Park adds that “banchan culture was created and evolved as a way to eat rice deliciously — and jang culture also evolved naturally as a way to create delicious banchan.”

The Korean Cookbook by Junghyun Park and Jungyoon Choi (Courtesy of Phaidon)

The Korean Cookbook by Junghyun Park and Jungyoon Choi (Courtesy of Phaidon)

Speaking of seasoned by fermented jangs (fermented soybean sauces) or jeotgals (salted seafood), Park notes the importance of the staple, from ganjang and gochujang to doenjang. “Korean fermented soybean paste, are seasonings that can impart deep flavors to any simple preparation and form the basis of almost all seasonings used in Korean cuisine," he said.

Park also mentions that comfort food's universality is shown throughout Korean food, especially when it comes to something like miyeok-guk, or seaweed soup. "In Korean tradition, one eats miyeok-guk on their birthday as this is the food that mothers will eat as their main guk after giving birth due to its nutritional content. This dish connects families and people: the mothers eating seaweed soup for postpartum care.” In addition, jiggae (Korean stews) in general — in all of its many iterations — can all feel especially restorative or comforting.

This reminded me, in Italian-American culture, of pastina — a grain that has deep, revenant importance throughout both Italy, America and many countries beyond that. Park continued, saying “All children, even through adulthood, remember and express gratitude for the grace of their mothers who gave birth to them and raised them by eating this soup in celebration of their birthday."

Kimchi, arguably the most widely recognizable and ubiquitous Korean dish (most likely followed by possibly bibimbap), is a dish that Park knew would need to be covered in depth. “Kimchi is iconic in Korean cuisine, especially as it contains all the defining characteristics that make up Hansik.” Namely: its intent (“bap and banchan pairing”), the importance of fermentation, its plant-based and “no-waste” nature and the sheer variety it brings in terms of flavor, color and more.

“Even the color of kimchi varies from white to green, yellow and red," he said. "It can be made with any vegetable throughout the year. It utilizes the most iconic technique of Korean cuisine, fermentation and can go to show how this singular technique can be applied to create a great range of flavors.”

Park also referenced kimchi’s place in Korean food and in the book overall. “This is a cookbook that contains the most common expression of iconic recipes, so rather than focusing on unique aspects of one recipe, we would like to highlight that these recipes are meant to express the overall concept of a food – such as kimchi – and then paint the example of the range within each type of food," he said.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

Technique is another aspect, outside of dishes and ingredients, that "The Korean Cookbook" explains in depth. “A fermented recipe is more delicious when paired with other banchan and eaten with bap, cooked rice, rather than when eaten alone. When kimchi matures and one can't enjoy it fresh, one can eat it in a variety of ways: making kimchi stew and kimchi fried rice are some examples of how to elevate the flavor no matter how mature. It is a dish that has no waste. "

If you're a neophyte looking to delve into Korean food, Park recommends the jjorim or bokkeum chapters as a starting point, or making a variety of banchan or "dishes meant to accompany rice,” to get things started and to acclimate yourself to the tastes of Korean food.

“One of the greatest charms of the unique bap and banchan culture that defines Hansik, and the way Koreans eat, is that the diner has such a great agency in creating their own flavor and dining experiences. Even as one eats communally – also a characteristic of Hansik – everyone can enjoy their own preferred flavor and texture combinations without overriding the entire experience for others.”

Park mentions the Korean saying "the cooking ends in the mouth," stating that "This speaks to the unique nature of Hansik, in which the diner has agency to create their own unique preferred combinations of bap & banchan."

Enjoying Park’s food — especially that inventive, original dessert — is a perfect indication of the way that Korean fundamentals, flavors and dishes influence his own work. No matter if enjoying Korean food at home or at a high-end Michelin restaurant, the flavors and aromas that have sustained and fulfilled generations will be evident in each bite, and Park is a liaison for bringing those flavors to new diners experiencing those dishes for the first time, as well as those who’ve already loved Korean food since childhood, ever since their first taste of miyeok-guk.

Shares