For climate conscious eaters, beef has become the food to avoid. That’s largely thanks to the outsized climate footprint of factory farmed beef, which contributes more greenhouse gases per serving to the atmosphere than almost any other food. More than half of that impact comes from methane, a greenhouse gas that’s about 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide in terms of warming the earth. Most climate experts seem to agree that reducing consumption of factory farmed beef is one of the most important shifts that developed countries can make to combat the climate crisis.

But what replaces factory farmed beef on our plates? For many people in the U.S., it’s factory farmed chicken, which has about one tenth the climate impact per serving. But some eaters might be surprised to hear that this swap isn’t as environmentally friendly as they think.

For most of history, chicken was a relatively rare indulgence — the occasional byproduct of egg production. But as farmers in the 20th century adopted the modern factory farm model, raising poultry solely for meat took off in popularity, dropping the cost of chicken dramatically and turning it into a household staple. Between 1940 and 2021, Americans went from eating an average of 10 pounds of chicken annually to about 70. And consumption appears to be rising with no end in sight.

Meanwhile, beef consumption has been trending down, even before recent widespread recognition about its carbon toll: Per capita consumption was nearly 90 pounds a year in the 1970s, but it’s less than 60 pounds today. The downward trend is partially the result of rising production prices that have made beef more expensive, even when adjusting for inflation. But the widespread availability of cheap chicken has also helped drive that shift, with chicken officially overtaking beef in 2010 as the most-consumed meat in the U.S.

Beef’s slump might seem like good news for the climate. But while chicken might have a leg up on beef in the emissions department, the overall rise in cheap chicken consumption is far from a win — for the environment, food system workers or the chickens themselves.

More than just methane: The big footprint of industrial chicken farming

So why do chickens have a better climate reputation than beef cattle? Cattle are “ruminant” mammals, meaning they have specialized bacteria in their multi-chambered stomachs that can ferment tough, fibrous foods into something they can absorb nutrients from. This allows them to eat a wide variety of foods that many other animals can’t process — but those bacteria are also the source of all those methane emissions. Chickens, on the other hand, are what animal scientists refer to as “monogastrics,” meaning they lack a partitioned digestive system and produce almost no methane, though they can’t handle the wide range of foods that ruminants eat.

At a glance, the carbon footprint of factory farmed chicken is dramatically lower than that of industrially raised beef: These chickens produce about 10 pounds of carbon dioxide equivalents (a standard measure of global warming impact) per pound of meat, while industrially produced beef’s footprint is ten times that per serving. Estimates put the beef industry’s total footprint at about 3 percent of all U.S. emissions, with most of that attributable to methane. Chicken’s contributions are comparatively minor, with its total contribution to U.S. emissions sitting at 0.6 percent. But that’s dependent on scale, and as the industry expands, so do its emissions.

Like all animals, chickens still produce a lot of waste — and chicken manure presents some unique problems, especially when there’s a lot of it in one place. And with 20,000 to 30,000 birds in each barn, that manure stacks up quickly. It is relatively concentrated in nutrients compared to manure from other animals and is especially high in nitrogen. Under the right conditions, much of the nitrogen in chicken manure can be made into useful fertilizer by bacteria in soil. When applied in concentrated form, however, that nitrogen volatilize, or transform into gases that escape into the atmosphere.

One of those gases is nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that’s 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Nitrous oxide accounts for a relatively small portion of all greenhouse gases — about 6 percent — but the amount of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere has increased by 30 percent in the last 40 years alone, and nitrous oxide accounts for nearly half of the U.S. agriculture industry’s climate impact. It’s hard to measure exactly how much comes from any one source, since excess synthetic fertilizers and other manures also emit nitrous oxide, but research has shown that poultry manure is more prone to releasing nitrous oxide than manure from other animals.

The nitrogen in chicken manure can also convert into ammonia, a gas that can cause skin, eye, throat and lung irritation in people who live near or work on chicken farms— and with higher exposures, even permanent lung damage. For birds, ammonia can cause serious lung problems at even lower concentrations than it does in people, which also increases their susceptibility to infections. Ammonia forms most rapidly in warm, moist conditions — like those inside of a giant chicken barn.

To manage ammonia buildup, chicken farms rely on giant extractor fans that push air out of the barns. But that ammonia has to go somewhere, posing a nuisance and — if it spikes to dangerous levels — potential health threat to neighbors. To make matters worse, much of that ammonia goes on to settle in water bodies. Combined with the excess nitrogen and phosphorus in runoff from the manure itself, this can lead to uncontrolled algae growth that robs water of oxygen and kills aquatic life. In the Chesapeake Bay, for example, researchers have identified that nearly 70 percent of ammonia from chicken houses ends up settling within 30 miles of where it forms, making the industry a big contributor to the area’s water quality issues.

That settled ammonia ultimately compounds the problems that excess chicken manure (which runs off of land into waterways) already causes: dead zones where aquatic life can’t survive, ultimately disrupting the entire food web. While fertilizer and manure form other kinds of industrial agriculture cause this problem too, the chicken industry’s footprint is unique because it’s so geographically concentrated. This puts all the pressure of the industry’s waste on just a few very important and delicate ecosystems rather than spreading it out around the country. In watersheds where chicken barns are common like the Chesapeake, the expansion of the chicken industry has been a major driver of water quality decline and accompanying drops in biodiversity and ecosystem health. Because these ecosystems where fresh and saltwater meet are so naturally rich, any nutrient pollution can have devastating and far-reaching impacts for food webs and unique species on land and at sea.

The unequal impacts of the chicken industry

Industrial chicken production is heavily concentrated in just a few places in the U.S., especially in the South and the Delmarva (Delaware, Maryland and Virginia) peninsula. Poultry processing takes a lot of work, so in the early 20th century, the burgeoning factory farm industry expanded in the South, where workers could be made to accept low wages, leading to the rapid expansion of chicken farms and processing facilities in largely Black communities. Today, those communities still pay the disproportionate price for cheap chicken: Entire neighborhoods are overwhelmed with the stench of chicken manure, and the high levels of ammonia in the air trigger asthma attacks and inflammation in vulnerable people who often lack healthcare access or the ability to move elsewhere.

In recent decades, the chicken industry has moved mainly towards immigrant labor, with a large percentage of workers believed to be undocumented. Their immigration status leaves them vulnerable to exploitation, as workers who speak out against unsafe conditions or other problems could be threatened with deportation or other retaliation by employers. Sadly, workplace dangers are part and parcel of the poultry industry today, with chicken workers experiencing rates of occupational injury that are well above the average. These injuries are often the result of increasing line speeds, the rate that birds move through the plant: Plants today can process 175 birds per minute, or nearly three birds per second. Accidents with knives and other equipment become inevitable in rushed environments like this, not to mention that long hours spent doing repetitive tasks can cause chronic problems like carpal tunnel syndrome.

The industry’s track record for fatal accidents is especially troubling: Eight poultry workers died in processing plants in 2022 alone. These kinds of accidents have made headlines numerous times in recent years, with some — like the suffocation of 6 workers in Georgia after a nitrogen gas leak — the clear product of negligence on behalf of the plant owners. As conservative lawmakers across the country weaken child labor regulations and enforcement, teen workers are getting killed, too: 16-year-old Duvan Perez died in a Mississippi chicken plant when he was pulled into the equipment he was cleaning, a job that, according to federal regulations, he was too young to be doing.

The business side of chicken farming is notoriously difficult for chicken farmers, too: Chicken production has been ground zero for the corporate consolidation and vertical integration that are now also wracking the rest of the meat industry. In the modern poultry system, farmers rarely own their birds. Instead, they are effectively relegated to the role of outside contractors for a few big meatpackers, taking on most of the costs of raising the company-owned chickens and having little choice but to accept low payouts and exploitative contracts. There have been some attempts to rectify this; the Biden administration has introduced some rules that require additional transparency around those contracts, and a class action lawsuit from farmers alleging conspiracy by chicken companies is moving forward. But overall, the problem persists. With only four poultry companies controlling 60 percent of the market, opportunities to get a better contract for raising chickens (or a buyer for raising your own) are still very limited. Many poultry farmers have been forced into debt, often choosing to quit farming altogether and leave larger players to scoop up their assets to produce even more birds.

The animal welfare case against factory farmed chicken

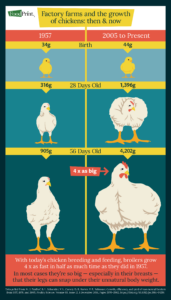

There’s also a compelling animal welfare argument to challenge the idea of chicken as a good swap for beef: By many metrics, chicken production is more cruel. As journalist Kelsey Piper explored in a 2021 piece for Vox, most conventional broiler chickens are born and raised completely indoors with less than one square foot per bird. That crowding makes it easy for diseases to spread, leading many chicken companies to renege on their antibiotic-free pledges and continue to overuse antibiotics that could accelerate the development of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Even if the birds had room to walk around, most modern broiler chickens have been bred to grow so quickly — with an average lifespan of just six weeks — that they can’t even move or even stand without pain.

Click to view a larger version of this graphic

Beef cattle, on the other hand, don’t have it as bad as other animals in the factory farm system. Even if their final moments are those of stress, confinement and misery, cattle still spend a good portion of their lives outside and experience cruelty and confinement mostly towards the end of their lives on feedlots and in slaughterhouses.

Click to view a larger version of this graphic

It’s hard to do clean math on something as intangible as suffering. But given the enormous number of chickens slaughtered every year in the U.S. — more than 9.3 billion in 2023 — that misery adds up quickly compared to the 32 million cattle slaughtered in the same period. Despite slaughtering nearly 300 times as many animals as beef, however, the chicken industry produces less than twice the amount of meat.

So how do we stomach killing this many birds? As animal rights lawyer and writer Elizabeth MeLampy points out in a 2021 paper for Systemic Justice Journal, many consumers see chickens as fundamentally less sentient (and therefore less capable of experiencing suffering) than animals like pigs or cows, which we perceive as being more like us. That indifference is furthered by how the industry talks about its product, using words like “harvesting” rather than “slaughtering.”

Chicken vs. beef is a false binary

Clearly, there’s ample reason to question the idea that conventional chicken is a big step up from conventional beef. The point is that both options are bad, and that a factory farm model is only going to produce bad outcomes regardless of what animals are involved. Alternative production systems can help alleviate some of those problems. In factory farming, there’s no opportunity to build soil carbon, which can help offset emissions from cows. Well-managed pastured beef helps build up that soil with the help of manure that’s well-distributed by animals themselves rather than pooling huge amounts of it in lagoons where it produces more greenhouse gases or contaminates waterways.

Alternative production systems for chickens also exist. The Department of Agriculture recently tightened its organic standards for poultry production to ensure that chickens raised organically get substantial outdoor access and have enough space to exhibit their natural behaviors. But organic certification does not ban overstocked barns outright, so while some welfare issues are improved, problems intrinsic to densely stocked chicken houses remain, especially waste buildup and the resulting pollution.

Chickens can also be incorporated onto pasture-based regenerative systems, where they can supplement their diets with insects and wild plants and where their waste will be absorbed into the soil in manageable amounts instead of polluting the surrounding air and water. You can find chicken raised this way by looking for pasture-raised birds from local producers at the farmers’ market, or by seeking out certifications like the Certified Regenerative by A Greener World, Regenerative Organic Certified, and the Real Organic Project. A Greener World also offers a more focused Animal Welfare Approved label that guarantees dramatically improved living conditions over conventionally farmed chicken.

But even if these alternative production systems can solve some of chicken’s problems, they accomplish that by producing a lot less meat than factory farms, underscoring the reality that we can’t just swap out one kind of meat for another; we have to be eating a lot less of it in the first place.

Making changes to the way we eat is going to be necessary in this current climate reality, but we have to consider all the tradeoffs associated with those choices. Yes, less methane is good, but it can’t be at the expense of all other environmental issues or animal welfare. It’s vitally important that we eat in a way that holistically supports a better system over all, and without question, swapping in factory farmed chicken in huge quantities is decidedly not the right move.

What you can do

- Read more of FoodPrint’s suggestions on eating less meat, but better meat.

- Check out FoodPrint’s food label guide, chicken.

- Watch the documentary film “Under Contract” about predatory contracts faced by poultry farmers.

- Learn more about industrial beef production and methane in our FoodPrint of Beef report.

- Learn more about factory farming of animals by watching “The Meatrix“.

Shares