Chef Fadi Kattan, whose new cookbook "Bethlehem: A Celebration of Palestinian Food" was released in May, says that he "couldn't understand and I still don't understand what's happening" in his home country, referring of course to the ongoing Israeli offensive in Gaza.

Kattan doesn't mince words, his immense passion and love for his country suffusing every word in our conversation. He says that he has "no words to describe the horror" and even sometimes "lose[s] the focus on what I'm trying to do."

As he puts it, though, "I still live in Bethlehem and for me, telling the story through food is telling the diversity of the Palestinians."

For Kattan, who comes from "one of the oldest Christian families in Bethlehem," championing Palestinian cuisine is one of the most important things. He discusses the varying terroir (the coast, the desert and the inland), the standout ingredients, what caused food to be so important in his life — both personally and professionally — and why food waste management and cooking sustainability are "not something new" and are something that have been practiced for generations. "It's not a trend," he says.

"What I have to say is cook Palestinian ... wherever you are," Kattan tells me, adding that he hopes people can "entertain the hope that we have that my book doesn't become an archeology history book, but is actually just a step in celebrating a lively civilization."

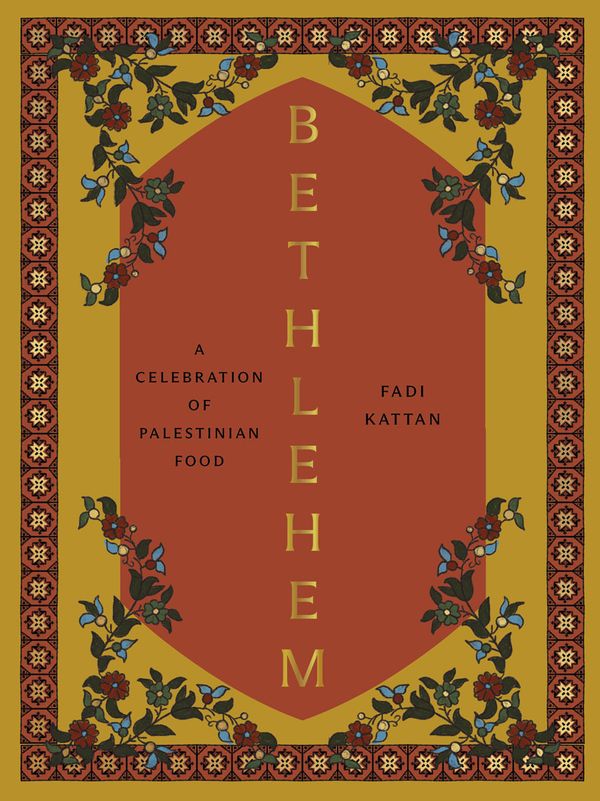

Bethlehem: A Celebration Of Palestinian Food by Fadi Kattan (Photo courtesy of Hardie Grant North America)

Bethlehem: A Celebration Of Palestinian Food by Fadi Kattan (Photo courtesy of Hardie Grant North America)

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

What does it mean to you to celebrate Palestinian food, especially in the current moment?

Celebrating Palestinian food is telling the story: the story of our culture, our identity, our traditions, but also the story of our perseverance, our attachment to the land, our attachment to those flavors, sharing it, sharing it with the world, and in those moments, in those horrible moments of a genocide happening in front of our eyes. It was very confusing in the beginning to cook, to celebrate the cuisine, but at the same time, I think it's a necessity. We have to be able to tell the story.

I'm sure there's a notion of frivolity to discussing food and ingredients at a time so full of strife, suffering and death. How do you reconcile with that? The book has come out at such a pivotal moment.

It has been very difficult. The first few weeks after the 7th of October, I couldn't cook. I couldn't imagine cooking, I couldn't understand and I still don't understand what's happening.

I have no words to describe the horror. We all have friends, family, people we know in Gaza and seeing the silence, the silence of many, too many, progressive liberal, cultivated people in the world in front of this horror, seeing the violence that's happening on the ground, but also the public discourse. Violence is suffocating. It is heartbreaking, it is infuriating and talking about food and ingredients and producers and artisans is quite a challenge emotionally. It is an emotional roller coaster.

I sometimes lose the focus on what I'm trying to do, which is to actually just say, we are there, we exist, we are human like anybody else, we're people that have a long history of everything and that long history includes food, that we are people that love life, like any other people.

I'll steal words from a Palestinian poet, Rafeef Ziadeh, that we teach life. I think teaching life is about always despite the darkness, having hope that humanity will prevail, that this madness will be stopped.

Bethlehem (Elias Halabi)

Bethlehem (Elias Halabi)

The book says that “cooking is how I tell Bethlehem’s story.” Can you speak a bit about that?

I grew up in Bethlehem. I still live in Bethlehem and for me, telling the story through food is telling the diversity of the Palestinians. I imagine that people dining with us or cooking from Bethlehem. The book, it will evoke the alleyways, it'll evoke the old stones. It'll evoke the vibrant feel in the market. It'll evoke the scent of spices. It's telling that journey. It's telling that path of food in my city.

Can you talk a bit about your family and your history in Bethlehem, both from a food context and within a larger perspective?

My family's one of the oldest Christian families in Bethlehem. They've seen a lot. They've seen hundreds of years of beauty and of challenge. They've seen the Ottoman occupation, the British occupation, the Jordanian presence, the Israeli occupation. They've seen the Intifadas, they've seen the genocide today and in spite of this, we stay. We stay because that's where we come from. That's where our roots are. That's where our story has been made and is being made.

"Palestinian cuisine is very much inscribed in the land of Palestine."

We've also left at different periods of time. My grandparents on my paternal side went to Japan and then India and the Sudan. On my mother's side, my grandfather grew up in France. He was born in Bethlehem, but grew up in France and those are not exceptions. Those are common stories that Bethlehem families have. I have at a larger scale, so cousins once and twice removed in some 79 countries, it's the people that have lived with history, with the roots, with the spice routes, with the trade routes, with the cotton route, with the souvenir route, the religious artifacts, all of that, and that's all led to people's travel. Now with the food context, I've grown up in my parents' house and my grandparents on both sides with a lot of different influences.

As a kid, I had maybe as much French food as Palestinian food, as Indian curries, as Italian food because of all these aunts and uncles being a bit all over the world — and I'm talking about aunts and uncles of my parents. From the empanadas of San Salvador to the bracciole of Italy, to the curries of India, to the French cuisine, all of that was very present because that traveled with the family also.

Are there any standout go-to ingredients that you prioritize within Palestinian food?

Sumac, zaatar, olive oil, laban jameed and those other champions of Palestinian cuisine.

Communal dish in Palestine (Ashley Lima)

Communal dish in Palestine (Ashley Lima)

For those entirely unfamiliar with Palestinian cuisine, what would you say are its trademarks, its signature ingredients, its ethos?

Palestinian cuisine is very much inscribed in the land of Palestine. To make it simple, we have three terroirs: the coast, the inland, which is the olive and fig landscape, and then the desert expands and the cuisine is designed around those three terroirs. It comes from that land, so the ethos of it is very, very short seasons that represent the season of Zatar, the season of spinach, the season of squash, the season of apricots and so forth, and that's the rhythm of that cuisine.

The signature ingredients come regionally. In Gaza, it'll be chili and dill. In Hebron, it'll be lamb meat. It'll also be a lot of grape derivatives, grape molasses, dibes. In Bethlehem, it'll be meat. It'll be dried yogurt. Laban jameed that comes from the bedouin tradition that's in proximity of Bethlehem. It'll be also vine leaves. It'll be arayes up north. It'll be goat yogurt instead of the dry yogurt, and the trademarks is a reflection of that land. It's a cuisine that's very, very close to the land.

We need your help to stay independent

Do you have a favorite recipe in the book?

All the recipes are my favorite. I designed all recipes with an approach of being able to be cooking them, to be able to make them easily, and that is the essence.

Would you say there's a good starter recipe in the book for those looking to prioritize or highlight Palestinian food?

I would say the easiest recipe in the book is the fig recipe, where you just slice a fig in fourths and sprinkle it with some olive oil and sumac.

For me, each mouthful is saying Palestine, and then from that, people can progress to slightly more complicated recipes, but none of the recipes are too complicated. I've designed all of them for people to be able to replicate and not only replicate, but also adapt. What comforts me is people using local seasonal produce, and that is essential for people to feel that they can adapt the recipes.

What stands out for you as a formative moment that got you into cooking or food at large?

Growing up in my grandmother Julia's kitchen, growing up in my mother Micheline's kitchen, the excitement of seeing the produce turn into delicious recipes, the excitement of hospitality, of seeing the house, being prepared for receiving guests, helping out, laying the table, helping out, preparing the food, all of those moments are moments that have really marked me and got me into wanting to cook.

Fadi Kattan (Elias Halabi)

Fadi Kattan (Elias Halabi)

Do you have any tips for cutting down on food waste?

Food waste management is not something new. It's not a trend. It's what our great grandparents used to do. When I peel vegetables, I use the peels to make a broth. When I buy meat, I buy it with a bone and I use the bones to make broth when I have leftovers and I rarely do. I have to think of how to use them.

I'll give you an example: The base of labaneh is fantastic because that creamy acid labaneh could actually take any topping on it, and you can just think of how to integrate whatever salad leftover you have, whatever herb leftovers you have onto the labaneh. You can do the same with freekeh. I very often cook freekeh and make a salad out of all the bits and pieces that I still have in the fridge. That earthy smoky flavor of the freekeh carries well a lot of flavors and it's easy to adapt.

How do you practice sustainability in your cooking and recipes?

I only source locally. Everything that is fresh in my recipes and in my cooking is sourced very locally, whether it's in London, Toronto, Bethlehem or Paris or wherever I'm cooking. I also make sure that all the producers are sustainable, and in that sense, I look at farmers that are growing in a sustainable scale, but also in a responsible manner.

"That emotion of sharing food with everyone is important."

I will always prioritize not using a specific cut of meat because in Palestine, we're lucky at the butchers you can take a quarter of a lamb and then use every bit in it differently. Then again, nose to tail is not something new. That's what we practice in Palestine every day and we've been doing it for hundreds of years.

Those are, for me, the essences of sustainability and of course managing waste. I always aim to have one and a half to 2% waste maximum, and in that approach we can all make compost. I do compost, we can all recycle. I don't use plastic, and all of that's very important to be able to maybe somehow give back what we owe to the planet.

What's your favorite cooking memory?

There's so many of them, but I'd go to a very recent memory. I cooked at the Refettorio in Geneva; the concept it offers is a paying lunch and then in the evening, dinner served for people from fragile backgrounds.

Cooking for people at large without any sense of who has to pay and who doesn't have to pay because you are just sharing that moment of pleasure is one of my most powerful memories. That emotion of sharing food with everyone is important.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

It’s obviously really difficult to prioritize or highlight tourism in Bethlehem or Palestine right now, but can you speak a bit about Kassa, the boutique hotel in Bethlehem?

Kassa is a passion project that was developed with Elizabeth Kassis, who's a Palestinian-Chilean. Her family bought what was originally their family home in Bethlehem before they immigrated to Chile in 1936, and she came up with this vision of our collaboration to create a boutique hotel, six rooms, the most upscale Bethlehem has to offer. In Kassa, it's a lot of other things.

It's highlighting Palestinian and Chilean artisans. It's offering the space inside the old city where people can stay and then go discover the city. What is great is they have a little map of the city that actually doesn't show tourism only. It shows where you can buy the best breads and where you can buy the best vegetables and herbs, and the idea is to have people stay longer in Bethlehem and actually discover all of that beauty of the city.

In speaking with Palestinian bakers, butchers, etc., how are they doing both professionally and holistically? It must be so challenging to focus on their business amidst all of that's going on.

You may have seen the short videos where when I went back home with the first copies of the book. I went to see the people I work with and who are in the book and I gave them copies of the book. What you haven't seen is the amount of tears and pain that we share because of seeing this genocide happening, of seeing the settler attacks in the West Bank, of seeing everything we believe in being threatened to disappear, everything that makes us who we are: those olive trees, the vineyards and the whole beauty of Palestine being so threatened.

I know when I talk to the winemakers we work with — and there's fantastic wine makers in Palestine — they share the same fear as the artisans, the butchers, the bakers, the farmers. Again, we've seen very recently another enormous land grab by the Israeli government in the Jordan Valley. Those thefts of land in Palestine by the Israeli government and by the settlers are scary.

What's happening in Gaza, it's been nine months that Palestinians are being massacred. The world's not willing to stop this, so we all have this fear. Professionally, it's a disaster. Bethlehem has seen tourism disappear on the 7th of October because people are no longer coming out there, and that's thousands and thousands of people who have lost their jobs, but the impact is also on all the purchases than from bakers, from butchers, from farmers . . . from everybody.

We don't have any social support from the government and therefore people who lose their jobs technically lose their income and go from an income to zero income. Nine months is a very long time. It's extremely worrying. The Palestinian economy is collapsing and that impacts everybody I love back home.

Palestinian Teta (Elias Halabi)

Palestinian Teta (Elias Halabi)

Tell me a bit about Teta's Kitchen. How did that come to be? Have you connected with any of the women since?

Teta's Kitchen came with a collaboration with an organization called PIPD, and it was just at the end of the COVID Pandemic. I had the time. They also wanted to create something where we tell the story of Palestinian food, and it was an incredibly emotional period where I was lucky to go into people's homes and cook with them. Also, in the case of the episode with Gaza — physically, as a Palestinian from the West Bank — I'm not allowed by the Israelis to go into Gaza, and this was way before the 7th of October, so we had a crew filming with in Gaza and I was in Bethlehem.

Very emotional moments of seeing that splintering of our country into pieces — disconnected. Every episode was very powerful, and then there was one in homage to my grandmother Julia, where I revisited her home that I haven't really been to much since her passing. I think that's the episode I can't really watch because the reason I cook is her. The reason I enjoy hospitality is her, and I hope I did justice to her in that episode.

I have connected with some of the tetas, most of them, but as you can imagine on the 8th or 9th of October, I tried calling Um Jayab, who's from Gaza, and luckily she was abroad. She was visiting one of her children that lives outside and she's safe. I wish I could say the same about every person in Gaza.

What would you say were some of the main takeaways from Ramblings of a Chef?

Ramblings of a Chef was the radio show and then the podcast that I started with Radio Alhara during the COVID Pandemic. It was incredible to see the support of people who are just curious, who were locked up at home, across the world, and people who are just curious about Palestinian food.

I also have to thank every cook chef, food writer who's accepted to be interviewed by me. Then, I did it quite rudimentary, using a phone, editing quite badly. Didn't know much about editing sound, and it was a great adventure, but it also allowed me to connect with a lot of people in thinking on how important food is for us.

How do you differentiate between Akub and Fawda?

Akub is in London. I cook with Palestinian flavors and British produce. It's very different than Fawda. Fawda didn't have a menu. I would cook with whatever farmers had in Bethlehem, and so there are two different ways of telling the story of Palestinian cuisine and they're both exciting.

Is there anything else you'd like readers to know about Palestinian cuisine or the current conflict?

It is not a current conflict. It's an ongoing 76 years of occupation and it's an ongoing genocide. It's not a conflict. The conflict is between two countries. What's happening, and that's not me saying it's international law, it's an ongoing occupation of Palestinian lands. It's the forced occupation on us by the Israeli government.

I have a lot to say about this, but I'd say one thing and it's a request for people who are reading this: Please don't fall in the trap that this Israeli government has said to equate what is happening on the ground to people's faith. This is not about Judaism, Christianity and Islam. This is a state called Israel that was created in 1948 on our lands without our consent that today is conducting a genocide against our people in a long context of 76 years of ongoing occupation, in breach of every international law, in breach of every UN resolution, and again, it's not me saying it. Look them up. Look at the UN resolutions. They're there. That's the international law that governs and should govern all of us as humanity.

About Palestine cuisine, what I have to say is cook Palestinian, wherever you are, and entertain the hope that we have that my book doesn't become an archeology history book, but is actually just a step in celebrating a lively civilization that's been going on for thousands of years, and that hopefully will go on for thousands of years in a more just humanity.

Shares